It’s an image that’s hard to forget once you’ve seen it. The cocky rock star at the front of the photograph gazes hard into the camera, right arm raised up and out in an unmistakable Nazi ‘Sieg Heil’ salute. To his right and slightly behind him, his bandmate replicates the posture. The serious look on his face is undercut by the finger raised to his top lip in an approximation of a Hitler-style toothbrush moustache, suggesting that, despite all other appearances, this is a joke.

But this isn’t Phil Anselmo at the Dimebash in January 2016. This is Metallica’s Lars Ulrich and James Hetfield, joshing around in a backstage corridor sometime in the early 1990s and replicating the posturings of a man whose entire ethos was built around racial purity, as 6,000,000 people found out to their cost. Funny, right? Ha ha. For all its protestations of inclusivity, metal has often had a thorny relationship with race. Phil Anselmo’s recent antics – yelling the words ‘white power’ while issuing his own variation on the ‘Sieg Heil’ salute – is just the most recent example of a virulent strain of nastiness within metal that stretches back years. From the avowedly racist dogma of sections of the black metal scene, to Guns N’ Roses’ infamous 1988 song One In A Million, to the ongoing debate over the connotations of the Confederate flag sported by various Southern rock bands, metal has been guilty of, at best, thoughtlessness, and in rare cases, outright hatred towards non-white people or culture. And what bands do, fans follow.

“I was at a Kyuss Lives! show in 2012,” says Laina Dawes, a New York-based journalist and photographer whose book, What Are You Doing Here? A Black Women’s Life And Liberation In Heavy Metal explores the scene’s relationship with race and gender. “I was walking through the crowd with my equipment and this guy jumped in front of me and got in my face and called me a ‘Fucking nigger’. I was in shock, and also I was embarrassed because everybody who was around stared at me like I was the one with the problem. I realised that if he had punched me, nobody would have done anything. There have been other shows where I’ve been threatened or I’ve had things thrown at me. There have been times when I’ve thought, ‘Why do I want to be part of this?’”

In the wake of Phil Anselmo’s bone-headed actions, it’s a question that’s more pertinent than ever – and one that white metal fans won’t ever be forced to ask. But it prompts another, even bigger question: does metal have a problem with race?

For a genre that prides itself on its outsider status, metal can be unwelcoming to anyone whose face doesn’t fit. Or, more specifically, their skin colour. Laina’s introduction to metal came via Kiss and Judas Priest, and she started going to metal gigs in the US in the late 80s and early 90s. She recalls being just one of “two or three” nonwhite faces at any given show.

“People would look at you funny or give you a dirty look, but no one would really say anything to you: ‘What are you doing here, you don’t belong.’” This changed, she says, in the mid-00s – for the worse. “There was more of a reaction. People seemed angry to see you there.”

She says that this was partly a response to hip hop’s cultural dominance over metal and hard rock since the 90s. “When the West Coast hip hop scene became prevalent around the mid-90s, it started to get notoriety as being as nihilistic as some of the metal bands, and there started to be a clear division in terms of race and music listening,” she says. “Black people listened to hip hop to be angry, white people listened to heavy metal. When the two genres converged with nu metal in the early 00s and you saw more white kids using traditional hip hop beats to accentuate heavy metal, that was a real problem for a lot of traditional metal guys: ‘We don’t like this merging.’”

Not everyone has had such bad experiences. Lasselle Lewis, drummer with Brit metalcore band Counting Days, was a kid when he first heard Metallica. His friends at school were surprised that he liked the band, but that’s as far as it went. “Maybe I’m just lucky,” he says today, “but I’ve always been made to feel welcome. I’ve never experienced any of the horror stories that people tell you. It was never a case of, ‘It’s not for you.’”

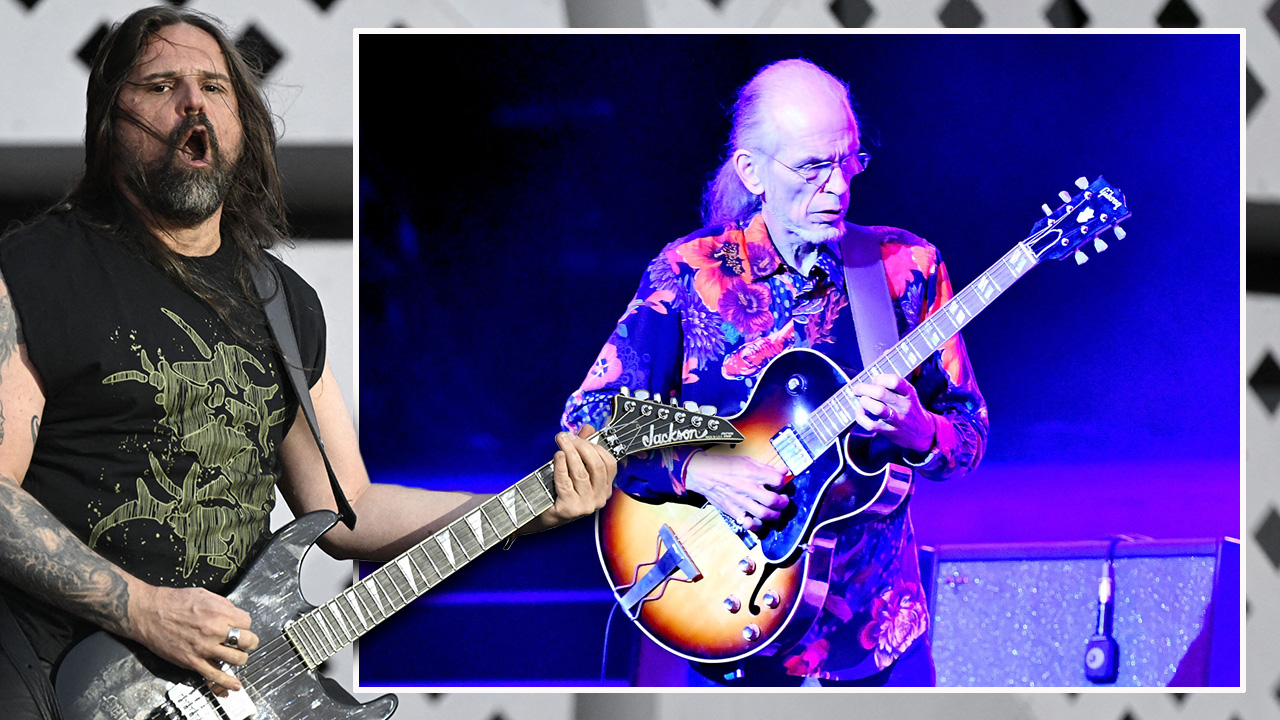

Doc Coyle is the former guitarist with God Forbid, the pioneering New Jersey band whose mixed-race lineup was unique in the mid-90s metal scene. Ironically, the first band Doc saw live was Pantera.

“Just because of the imagery of that band, there was definitely an inkling of a thought in our heads that maybe we wouldn’t be welcome here,” he recalls. “There was that feeling, ‘Oh, there’s gonna be skinheads here.’ There was some apprehension. But honestly, by the time we were in our seats, all that had floated away.” Doc – who now plays in Vagus Nerve – admits that he was fortunate to get involved in the diverse New Jersey hardcore scene. “Even though it was predominantly white, everyone was involved: Hispanic people, black people,” he says. “It was much more integrated.”

Even so, when he and his brother Dallas formed God Forbid in the mid-90s, it was assumed they would play ‘black’ metal – a sort of dubious musical racial profiling. “Because of the racial composition of the band, people thought we would be playing rap-rock, or reggae like the Bad Brains,” he says. “But we were a straightahead metal band. There was nothing definitively ‘black’-sounding in the music we played. If anything, it made us stick out.”

That raises the question of whether music can have an ‘ethnicity’. Go back far enough, via Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath and the other big beasts of 70s rock, and you can trace metal’s roots to the blues. But the musical and cultural influence of the blues on modern metal has became so diluted that it’s barely noticeable.

“If you look at origin and prominence, I would say yes, metal is a ‘white’ music,” says Doc. “A lot of metal’s values are very European-based. The more ‘European’ you appear to be in sound and look, the more ‘true’ metal you are perceived to be. Like Amon Amarth – they evoke this Nordic, Viking thing, tall, blond hair, stoic. That’s part of the aesthetic. But you can use the reverse. If you have a rapper who comes from a low-income, crime-oriented area, they’re going to be seen as more authentic. Hip hop came from a certain set of ideals, a certain point of view. You can’t tell me that culture doesn’t have something to do with the way music is created. And I think that’s fine.”

But, says Doc, that’s not the whole picture. “Talking about ‘white culture’ and ‘black culture’ is very binary. Metal is very popular in Asia and Central America. If you’re Iron Maiden and you play in India, you’re mostly going to play to Indians. There’s a global scene that isn’t tied to racial boundaries.”

All of this is playing out against a bigger backdrop. Rightly, there’s a broader conversation about race and diversity going on right now, from Beyoncé’s politically charged appearance at the Super Bowl to the #oscarssowhite controversy at this year’s Academy Awards. But in the metal scene, that diversity isn’t being discussed in any form.

“Diversity is important because of common sense,” says Laina. “The world is changing, everybody has the right to participate actively in the music scenes they want to.”

It’s ironic that metal seems to be burying its head in the sand on this front, especially since it has always positioned itself as a haven for the dispossessed and the underdog. “There have been so many negative stereotypes about the people participating in the scene – class issues, drugs uses, Satanists,” says Laina. “It’s, like, ‘We’ve been stereotyped and insulted, so we’re going to make a concerted effort that everyone will be inclusive in the scene, as long as they’re a metalhead.’ But that kind of thought, that traditional idea of what metal means, has become a problem because it’s not true. We’re seeing that people are not accepted in the scene because of their ethnicity. And that, to me, makes absolutely no sense.”

Napalm Death frontman Barney Greenway has spent most of his life confronting racism (as well as fascism, homophobia and misogyny). While he acknowledges that, as a white man, he will never face the same oppression from within the metal or punk scenes as someone of colour, he’s unrepentant in his desire to rid the genre of its prejudices. This has frequently spilled over into physical violence, with the band being confronted by far-right groups such as the Aryan Nations.

“For the sake of fellow human beings, you cannot cower in the corner,” he says. “It’s not anything to do with bravado – it’s about the fact that everybody should be able to express their right to exist and move in certain circles, and not be fucking harassed because of their skin colour, or sexuality.”

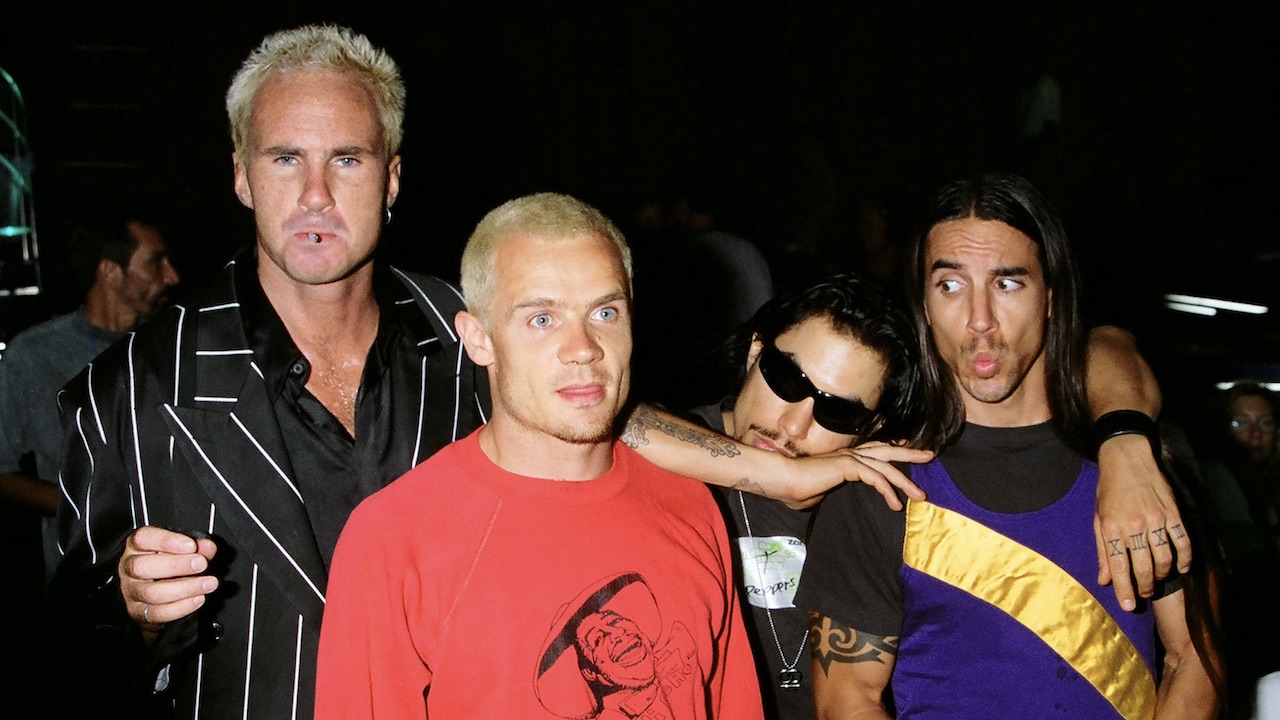

Of course, there’s no reason metal has to embrace diversity – it’s managed to plough its own furrow for close to 50 years now without being dictated to by wider society. When it has engaged with other musical forms – the funk-rock explosion of the late 80s and early 90s, nu metal’s appropriation of hip hop in the late 90s and early 2000s – the results have broadened the genre’s scope. But there’s no arguing with the fact that non-white musicians and fans are a minority within the metal scene. Partly, this is down to the stereotypes that surround metal in the view of the outside world.

“In some ways it’s a self-perpetuating thing,” says Laina. “There’s still this resistance because it’s loud and angry and aggressive, and not everybody wants to listen to it. And there is this stereotype, where people see heavy metal as being a bastion of racism. They see the people who are listening and playing the music as being the same people who threatened to beat them up on the street. There are a lot of stereotypes that hinder active participation.”

Lasselle Lewis suggests that you can’t force diversity. For him, listening to metal is a defiantly personal choice. “Almost everyone I’ve played metal to who doesn’t listen to it either says, ‘Why is the vocalist shouting?’ or ‘Why is the music so loud?’” he says. “They can never really get past the shouting to accept and fully appreciate the music, which to me has nothing to do with race but more a personal preference thing. So in order to attract more people of diverse cultures into metal I think metal itself would have to change, but if that happened I think we’d probably lose more than we would gain.”

Of course, there’s one person casting a huge shadow over any discussion of race in metal in 2016. When Phil Anselmo screamed the words “white power” and gave a Nazi salute at LA’s Lucky Strike Live club during the Dimebash tribute show, it was simultaneously crushingly disappointing and ultimately unsurprising. The former Pantera man had form on that front. In 1995, he gave a rambling onstage speech decrying rap culture and suggesting that a Pantera show was “a white thing”.

“That video – ‘proud to be white’ – it’s not a great feeling that you get watching it,” says Doc Coyle. “I watched it a few years ago, and it didn’t lose any of its impact. In fact it feels a little more impactful now because of what just happened.”

Phil’s initial defence for his actions earlier this year – that he was drunk and that it was a “joke”, with some tenuous connection to the white wine he’d been drinking backstage –was, if you’re being generous, feeble, or plain unbelievable if you’re not. The reaction from his fellow musicians was both swift and heartening: Robb Flynn led the charge with an impassioned 11-minute video calling out Anselmo, while Anthrax guitarist Scott Ian also criticised the singer. For Lasselle, the incident prompted a different reaction.

“To be honest, I’m probably one of the worst black people to talk about that!” he says.n“I’ve never really been at the far extreme of thinking: ‘Oh my god, I can’t believe he said that’,” he says. “I had a bit of a reaction to it, but for the most part I was like, ‘OK then…’ I accept it as just the way he is. It didn’t make me think, ‘I’ve got to stop listening to Pantera now.’ I do think it’s a very American thing, though. I can’t really picture it happening over here. I think they’re two different worlds.”

It provoked a similarly mixed reaction in the broader metal community. Many online commentators viewed Phil as an out-and-out racist, while others still simply agreed with him: “Yeah, white power, dude!” One common defence for his actions was the particularly American viewpoint in which anyone can say whatever the hell they want, no matter how offensive it might be: it boils down to the freedom of speech versus political correctness. This is where the narrative about race in metal starts to diverge.

“These people who say that need to understand, what is political correctness?” says Laina. “Why would you just want to hurt someone with words? Metal is nihilistic – I understand that. And I understand that there’s offensiveness in the music. But when it comes to hurting other people, or disparaging women, I don’t understand how anyone would want to accept that. [The people who say that] are people who have not been in situations where they have had to deal with racism or homophobia or anti-Semitism, so it’s easy for them to spout off and say a bunch of bullshit, because they don’t have the personal experience.”

This is something that Doc disagrees with. “It’s about what you value – if you value the open highway of ideas over sanctity, then you’re going to hear some abhorrent and objectionable things,” he says. “Freedom of speech doesn’t exist for nice things. It’s ugly, it’s not always things you want to hear. But let’s go and win the intellectual argument. That’s why ideas like these are fringe ideas – they always lose under the weight of logic.” The other question Phil Anselmo’s antics raises is whether you can separate art from the people who make it: should we carry on listening to music made by people who say dubious things, whether that’s Phil Anselmo or a genuine extremist like Varg Vikernes of Burzum?

“No. I think it’s very subjective, and it depends on the person you’re talking to, but for me personally, no, and it hurts my soul,” says Laina. “I love Down. I think they’re a fantastic band. But I cannot, in all conscience, give them my money. I won’t do it. And Burzum? As a black woman, there’s no goddamn way. Varg Vikernes has been very clear in what he’s said about my people, about Jewish people, about gay and about lesbian people. When you have white men saying, ‘I don’t understand why people have a problem separating the music from the beliefs’, it’s because they’ve never been in a situation where they’ve been physically threatened or assaulted, or made to feel like they don’t belong.”

Which brings us back to the $64,000 question: does metal have a problem with race? In his wrong-headed outburst at Dimebash – and with his past actions and associations – was Phil inadvertently holding up a mirror to the genre itself?

“Metal has no more of a problem with race than regular society has a problem with race,” says Doc. “Does regular society have a problem with race? Oh, most definitely. I can only speak for America, but Americans in general have unresolved issues. Metal is just a piece of that.”

“Metal is only a microcosm of anything else, so in that regard, absolutely fucking right it does,” says Barney Greenway. “Even now, when we go certain places, it is definitely still there.”

“Not only does Philrepresent ignorance, but he’s been able to build a prosperous career even though people know that he holds views that alienate people from the scene,” says Laina. “He can say whatever he wants to say and believe what he wants to believe, but I think the larger problem is our willingness to ignore issues that ostracise people from the scene. And it’s not even a matter of alienation. My concern is physical violence. We’re seeing that it is happening to a lot of women in the scene, and it’s happening to people of colour who are getting beaten up. For people to blindly ignore sentiments that Phil has that lead to not just physical violence within the metal scene but the murder of people in the real world is unconscionable.”

For anyone on the receiving end of racial abuse at a gig – be it verbal or physical – Laina suggests fighting back. “Is that the smartest thing to say? Definitely not, because you can get your ass kicked if you get into a fight. But when you do say, ‘Fuck you’, that’s when people start getting scared. You have to break that cycle of abuse and stand up for yourself.”

For Barney, metal fans have a responsibility to kick down the barriers thrown up by racism. “We shouldn’t even have to work towards it,” he says. “Why should there be a barrier there in the first place? You take people as they are. And if you have a problem, it shouldn’t be defined by the colour of their skin or whatever. That to me is making more difficulties in life than is necessary.” If metal does have a problem, whether that’s to a large or small degree, then it needs a solution. But, according to Doc, silencing the racists isn’t it.

“I don’t believe in censorship,” he says. “You let these people put their ideas out there, and they have to win in the debating field of ideas. You can’t try to regulate what people think. There’s always gonna be assholes, but if they’re gonna be assholes, let them do it in public. That way we can go, ‘You’re a dick, and I’m not going to hang out with you.’”

Ultimately, change has got to come from within. In the metal scene as in the real world, you’re either part of the problem or part of the solution.

“People need to acknowledge that there’s a problem,” says Laina. “There should be more articles written about this, there should be more reports of people’s behaviour and what they say. People need to have some balls. They need to put themselves on the line and confront these issues, and not push them under a rug.”

WHAT DO YOU THINK? HEAD TO FACEBOOK.COM/METALHAMMER