With its evocative but obscure lyrics rooted in 1950s nostalgia, politics and romance, American Pie was one of the dominant sounds of the 70s, and brought previously little-known songwriter Don McLean worldwide fame at the age of 26.

The song – covered over the years by artists as diverse as the Brady Bunch, Killdozer, “Weird Al” Yankovic and, most famously, Madonna – and the self-titled album it comes from turned 50 last October, and McLean has embarked on a celebratory tour, having just finished recording a new album, written a children's book based on the song, launched a YouTube channel and received a star on the Hollywood Walk Of Fame.

“There’s all sorts of crazy things happening for old Don,” he tells us. And tanned, in shades and sporting the signature McLean mane of hair, he’s ready to reminisce.

“I was a singer from the time I was born,” he says, taking us back to 1945 and his childhood home in New Rochelle, a leafy, middle-class city 25 miles from the centre of New York. McLean’s home life then had parental distance in it, and a troubled elder sister, Betty Anne.

As a kid, McLean was often ill in bed for weeks with asthma, missing his school friends and education terribly, but had the radio for company and learned “hundreds of pop songs by heart” from performers such as Nat King Cole and Bing Crosby.

By 1955, when he was 10, “everything changed,” McLean says. “It went from the postwar kind of world to rock’n’roll. With Elvis Presley, the Everly Brothers, Buddy Holly and great black bands such as The Penguins and The Flamingos, the music was brand new and it was ours.”

The McLeans had a piano, but his creative world opened up more thanks to the ukulele boom of the time. “I learned a few chords,” he recalls, “but each step of the way I told myself: ‘You can’t do that, you’ll never do that…’”

However, his friend Brad Bivens had a guitar. They played baseball together, and McLean would go back to Bivens’s house to listen to records by Duane Eddy, Josh White, Django Reinhart. “He said: ‘I’ll show you a few chords’, and he showed me E, A and B7. I was on my way, with three chords and a capo.”

Between the age of 12 and 16, McLean had his one and only “job”, as a paperboy for local newspaper the Standard Star. The money he earned from it went towards his first guitar, a Harmony F Hole semi-acoustic. Soon he and Bivens were playing rock’n’roll songs at dances. His sister paid for him to learn to sing opera, and combined with joining the Orienta Beach Club swimming team, McLean’s breath control and stamina improved, lessening the effects of his asthma and establishing a determination: “It taught me to put up with the struggle – I’m not a quitter.”

In 1958, McLean discovered folk music after his uncle Malcolm played him records by folk song collector Frank Warner, and also from hearing The Weavers’ At Carnegie Hall. The Weavers featured folk beacon Pete Seeger, and mixed politics with music, putting a spotlight on songs of social strife by artists such as Woody Guthrie and Lead Belly. McLean felt that he “truly understood folk music’s purpose”, and decided to extend his reach beyond his three chords.

He called The Weavers’ songwriter, Erik Darling, who invited him to his New York apartment for a music session. Impressing the band with his attitude and knowledge of their work, they became friends, and by the start of the 60s McLean was being mentored by Seeger. He was then picked up by Weavers manager Harold Leventhal, who also had Joan Baez, Woody and Arlo Guthrie and Judy Collins on his books.

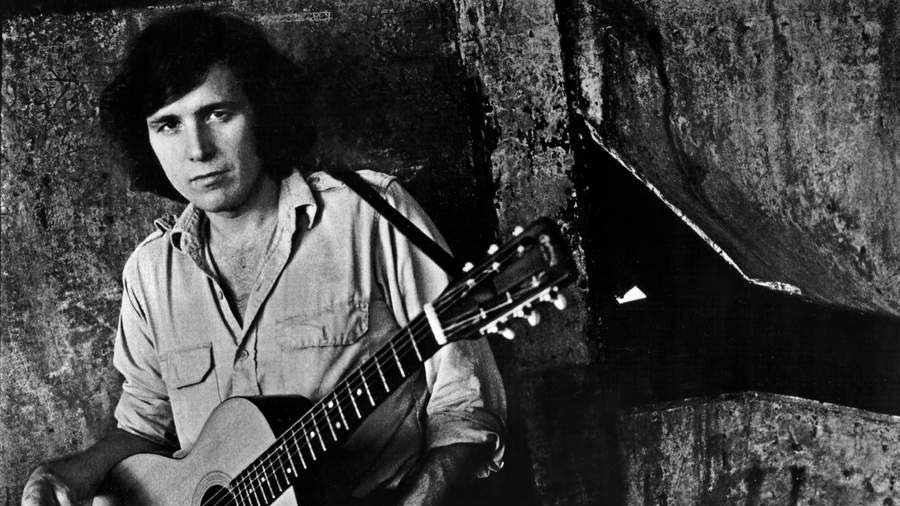

“The folk scene landed in my lap,” McLean says. “I was a guitar picker, I was young, pretty, I had a lot of hair, I sang well and I wrote some pretty good songs. Suddenly I was playing nightclubs and had an agent. There were clubs on college campuses, in hole-in-the-wall store fronts… folk music was everywhere. But the best part about it was that I was free to create and use the guitar, and to travel and sing. I didn’t have to take orders or work for anyone.”

The folk scene wasn’t always a love-in, though. “The scene was a bunch of fairly arrogant sophisticates who considered themselves to be purveyors of American culture,” McLean recalls. “They were giving America its own music, which they’d gone around and collected. You had to be ‘authentic’, and nobody’s authentic – Pete Seeger was a Harvard dropout, he had no business singing cowboy songs as much as I did.”

However, McLean’s time with Seeger was enjoyable. “Pete helped people get gigs and get signed. The problem I had is that after a few years everyone around him hated America, and I didn’t like that so I backed away. But I loved knowing him. I learned resilience from him – he would make some clangers on stage and it wouldn’t bother him, he would just carry on.”

In 1969 McLean appeared at the Newport Folk Festival. Among its big acts were Johnny Cash and June Carter, Champion Jack Dupree, the Everly Brothers, Son House, Joni Mitchell and Van Morrison.

This sowed a seed for the song that would become American Pie. When McLean was a paperboy, the horror of Buddy Holly’s death featured on the front pages of the papers he distributed.

“I’d carried the Buddy Holly saga in me for ten years, until I met Phil Everly at Newport,” he says. “I said to him: ‘I know you were really good friends. What happened?’ And he said: ‘Buddy had to stay back to do his laundry, so he took a plane to catch up’ [with the bus crew]. When he said that, it shook me up. I was suddenly aware of that touring’s not all standing ovations, it’s hard work. Some ideas began to percolate in my head.”

Meanwhile, McLean had an album’s worth of songs and no deal. “I had a new manager, Herb Gart, who knew talent but had no idea what to do with it,” he says. “He had some acts that were popular at the time, like The Youngbloods and Buffy Sainte-Marie. I was impressed with him in that way, but he’d just let business go and was a disaster.”

McLean went from “having a life that was orderly, to free-fall”, owing thousands of dollars, until, through filmmaker Bob Elfstrom, he got a deal with Alan Livingston’s Mediarts label. Livingston had signed The Beatles to Capitol Records. McLean says, quite rightly, that he’s “one of the great record men of all time”.

His debut album, Tapestry, was released in 1970 to modest success in 1970. It featured the US hit Castles In The Air and the ballad And I Love You So, which three years later would be a big hit for easy-listening singer Perry Como, and become a favourite cover song by McLean’s ultimate hero, Elvis Presley.

Happy that his music was finally on record and making an impression (Tapestry’s title track inspired the formation of environmental organisation Greenpeace), he started putting together the album that would become American Pie. Mediarts was acquired by United Artists and McLean says he “made American Pie for Alan”

The song inspired by Buddy Holly (the whole album is dedicated to him) became the centrepiece. At eight and a half minutes long, it’s themes and imagery seemed to signal the end of innocence of one era and the darker days of the future. The single took three months to climb to No.1 in the US in January 1972, and seemed to be in the ether, everywhere, forever after. It is now recognised by RIAA as one of the top five songs of the 20th century.

McLean understands its impact, but back then his ambition was moderate. “I had two albums out,” he says. “I bought a little house and could afford my taxes. I was pretty happy.”

Over fifty years on, McLean has never stopped working and continued to have hits including Vincent, his poignant tribute to Van Gogh, and a cover of Crying that its writer Roy Orbison preferred to his own version. His connection with his audience was also the inspiration for Lori Lieberman’s 1972 co-write with Norman Gimbel Killing Me Softly With His Song, another song with an incredible, long life.

McLean’s new album, thus far titled American Boys, will be released soon. Although he says he’s not political – “I don’t like political people. They’re pedantic and they bore me. They have all the answers and they don’t know shit” – he has documented the current social climate in the US.

“I recently wrote The Ballad Of George Floyd,” he says, which might make him even more popular with the younger artists who already cite him as an inspiration, such as Canadian rapper Drake, who sampled two obscure 1977 McLean songs for his millions-selling/streaming 2011 track Doing It Wrong. Of course, he might not be in this position were it not for American Pie.

“I needed that record to happen, desperately,” he says. “I would have been out on the street with no record deal, and whatever little momentum I had behind the Tapestry album would have dissipated. “No matter what happened, though, I always had these songs which buoyed me up. And I’m really happy to be defined by them.”

For tour dates, check the Don McLean website. His new children's book, Don McLean’s American Pie: A Fable is published in June.