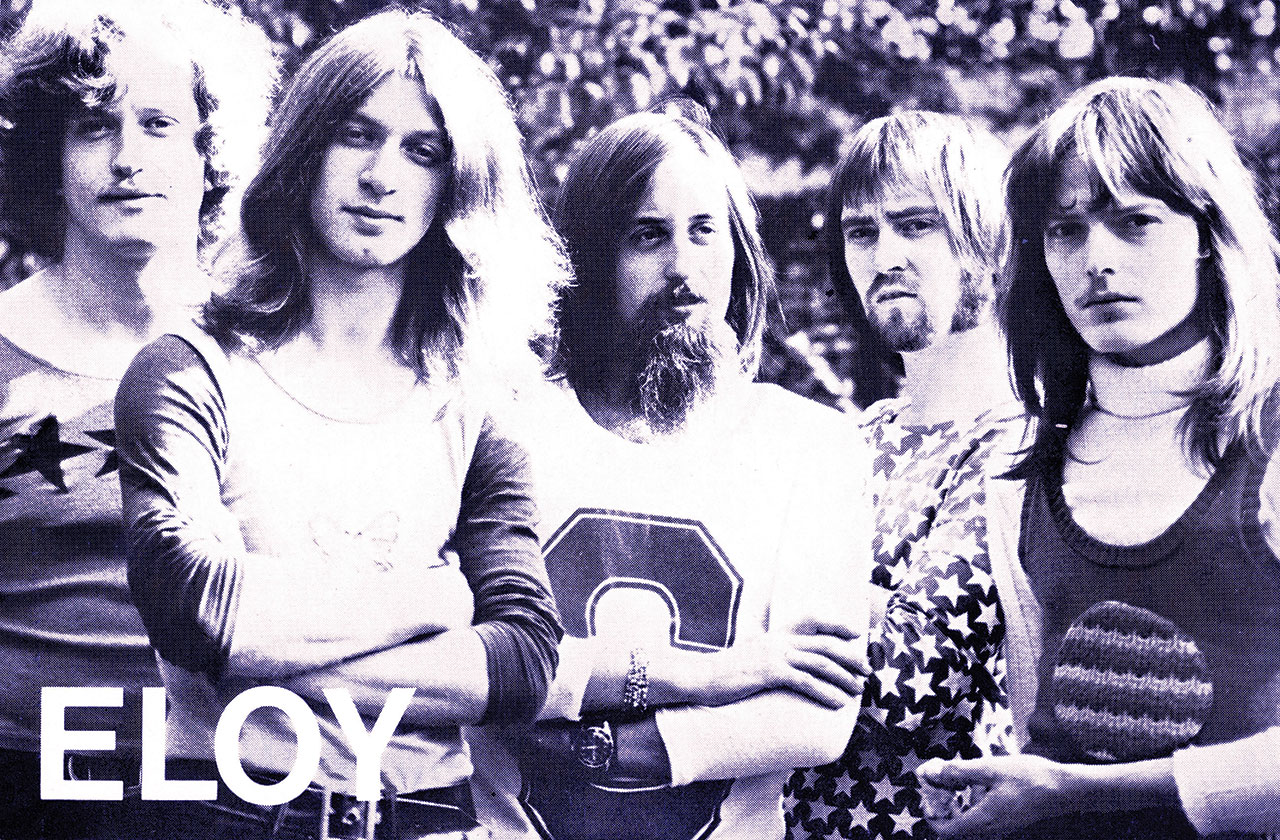

Adored by a huge fan base in their native Germany but very much a cult concern everywhere else, Eloy must surely be progressive rock’s greatest unsung heroes. Founded by singer/guitarist Frank Bornemann in Hannover in 1969, they emerged at a time when all eyes were on the English scene and the very notion of German prog rock was still in its infancy.

Against the odds and 50 years on, Eloy are very much alive and well and enjoying a fresh surge in popularity following the release of elaborate new concept piece The Vision, The Sword And The Pyre. Bornemann may now be in his seventies, but as he graces Prog with an impressively detailed history of his band’s five decades, his energy levels and unbridled enthusiasm for making adventurous music remain undimmed. That said, he does note that Eloy very nearly fell at the first hurdle.

“In Germany it was very, very hard at times, particularly in the very beginning,” he recalls. “There just weren’t that many bands in Germany that played their own music at that time. We started in 1969 and our first steps, well, let’s just say that it wasn’t a brilliant start. We made one album for Philips (1971’s Eloy) and it was a complete flop. So I changed the line-up and we tried harder to find our own style of music. We were influenced by some English bands, of course, like Genesis, Jethro Tull, Pink Floyd and so on, but we were determined to find our own thing, which wasn’t so easy in the beginning.”

The accepted wisdom about Germany’s contribution to the prog rock realm in the 70s is that the wildly experimental efforts of Can, Faust, Tangerine Dream and Amon Düül II were the only show in town. In truth, the Krautrock movement existed in parallel with a more recognisably prog-inclined splurge of bands, all of whom were somewhat overshadowed by their more consciously cool fellow countrymen and the heavyweights of the English prog scene, despite producing some extraordinary music along the way. Eloy’s second album Inside is a great example of how distinctive German prog swiftly became: released on Harvest Records in September 1973, it single-handedly confirmed that Germany had its own credible prog rock force, even if the world at large was to remain stoically immune.

“We had signed to Harvest and it was the home of Pink Floyd and Deep Purple and other famous groups, so I was very pleased about it!” Bornemann remembers with a chuckle. “Inside was the first step in a new direction. That one was released in the United States too and it was quite successful. And now we were doing okay in Germany. We played many, many concerts, and over time we became more and more popular at home.”

Buoyed by vociferous support from German rock fans, Eloy’s second crack at the whip proved to be decisive. The next few years saw the band release a steady succession of bold, ingenious and idiosyncratic albums that enabled them to consolidate their support at home while gradually accruing attention from other parts of the world. Unfortunately, as Bornemann recalls with a rueful sigh, Eloy were seemingly cursed to undergo relentless line-up changes and sudden splits. However, their leader’s good-natured determination somehow propelled them onwards, and by the late 70s Eloy were enjoying major commercial success in Germany.

“I was also producing the band by that point,” says Bornemann. “The first one I produced was Dawn [1976] and that was our first very big success in Germany. The follow‑up, Ocean, was the best-selling progressive rock album ever in Germany. We sold 350,000 copies, which is a lot! But then I thought we had to come out with something different and so we made another album, Silent Cries And Mighty Echoes, and that was also very successful in Germany but, once again, there was a lot of quarrelling in the band. So, once again, we split!”

As with most bands that survived prog’s late-70s downfall, Eloy were an intermittent and sometimes tentative force during the 80s. Bornemann’s quiet persistence kept the show on the road for the most part, even when the band were reduced to a two-man unit (the other man being keyboard player Michael Gerlach) for 1988’s Ra album and the six years that followed it. But international success continued to elude them, despite occasional forays into the wider world.

“We did play shows in America in the 80s and they were very successful,” Bornemann notes. “We also played in England, at the old Marquee Club. That was one of the greatest moments of my life, I must say. The response in England was incredibly positive. So we were accepted in many other countries, but it didn’t compare with our German success. We had an artist contract with EMI in Germany for 12 years but our record company was not able to build or support our career in foreign countries. Unfortunately the band split up right after our successful concerts in America. That was a great mistake. We were getting offers from very good agencies in England, but sadly it was all in vain. I had to start from scratch and it wasn’t the best conditions for sustaining the success. I had no musicians! [Laughs] It was just Michael and me for six years almost, but I also produced a lot of heavy metal bands, like Helloween for example. I had to find a way to survive, for economic reasons, but it was very interesting.”

Thanks to the necessities of financial survival, Frank Bornemann now has a formidable reputation as a producer, but it’s obvious that he has only ever viewed the job as a means to an end. In fact, he has just retired from producing other bands and has thrown himself wholly into the task of creating new Eloy music. The first results are The Vision, The Sword And The Pyre Part I, the band’s first album since 2009’s much acclaimed comeback effort Visionary and, unquestionably, the most wildly ambitious record Bornemann has ever produced.

“From my side, Visionary was a thank you to the fans, who kept the band popular and kept the band alive around the world for all these years,” he states. “Then, when we decided to play live again, that was an amazing success too. So then I was asking myself, ‘What can I do now?’ And that is how The Vision, The Sword And The Pyre came to be.”

The first half of a sprawling and almost alarmingly detailed rock opera based on the life and times of Joan Of Arc, the new Eloy album is a gloriously extravagant and atmospheric affair, and a self-evident labour of love. The result of many months of exhaustive research, coupled with Bornemann’s rejuvenated songwriting, it’s the kind of grandiloquent statement that could easily fall flat on its face. But, once again, Bornemann’s rapacious dedication has ensured that the whole thing hangs together beautifully.

“I had a dream since the early 90s that I wanted to make a record about Joan Of Arc,” he says. “That’s the simple reason why I started to do it now. I adore Joan Of Arc. In the 90s I started to speak with writers and historians in France, I watched all the movies and I read many books about the subject, maybe every book there is! I must say I know the story very, very well, but the films always disappointed me. They never get it right and the story is never complete. No one ever seems to notice that Joan Of Arc had so many problems with her service and so many mixed emotions because of the war and the activities on the battlefield. She was a person with a big and complex love and compassion. Even for foes and enemies, she had compassion. But I never noticed that in any of the movies. It would always be a very compressed version of what happened. So I wanted to write something that would bring Joan Of Arc much closer to the audience than ever before, something more emotional, with more details. That’s why I need two albums to do this!”

Prog is no stranger to historical narratives, of course, but it’s incredibly rare to hear an album that prides itself on meticulously conveying the truth, rather than revelling in the mischievous possibilities of artistic licence. In truth, The Vision, The Sword And The Pyre is a sincere attempt to shine a light on a legendary life, one that was lived with the kind of values and respect for humanity that appear to be under siege in the 21st century. Bornemann is making no attempt to draw a specific political or social allegory here, but there’s no mistaking the album’s overriding air of exasperation at man’s cruelty to man and our inability to learn from our mistakes.

“Joan Of Arc was a true and honest person. The way the world is at the moment and the kind of situations we have, with so many problems, I think the behaviour of people of honour is an incredibly positive thing and it has a positive influence, by teaching these important values, of compassion and respect. She had all of that and demonstrated it through her life. No one could give more for something than she did, and that’s an important lesson at any time in history. Okay, so the problems we have today are different, but this is also a very hard time and a big challenge for all of mankind.”

Speaking of big challenges, Frank Bornemann is about to embark on an even more ambitious project. Currently working on the second part of The Vision, The Sword And The Pyre, he has plans to turn the whole two‑part caboodle into an eye-frazzling stage show, its premiere expected to take place in France, where Eloy have long retained a passionate fan base. With typical attention to detail, Bornemann has been learning French for many years and plans to translate the entire album into the language for its live incarnation. Even more impressively, Eloy hope to be taking this unashamed rock opera on the road, with onstage spoken dialogue translated into the language of each respective territory.

“In France, they call it ‘spectacular musicale’, although it’s not a musical in the traditional sense because I hate to have sung dialogue,” Bornemann explains. “For foreign countries, the music will be completely in English and then the spoken word will hopefully be in the language of the country we’re playing in. That’s my concept and my hope. In France they’re very interested in helping me to make this all happen. When I finish the second part of the album, which will be next year, I will have to write everything again from scratch in French and that will be very difficult. The languages don’t work the same at all. I started to learn French from the ground up, but I’m still learning. There are not enough clear words in French – nearly every word has many different meanings. It can be very frustrating! [Laughs]”

72 years old and still thoroughly obsessed with the refined art of making daring, dramatic music, Frank Bornemann may still be an unsung hero but he really doesn’t care. Instead, he’s thinking big, speaking the truth and loving every minute of it. Joan Of Arc, you may speculate, would wholeheartedly approve.

“No one else is trying to produce a rock opera right now, that’s for sure!” he laughs. “It’s very expensive and it takes a long time, so it doesn’t happen very often, but the response has been very positive. I’m astonished because at the beginning I thought that a rock opera with so many spoken parts would be a little bit dangerous! But somehow it works and I’m very, very happy.”

This article originally appeared in issue 83 of Prog Magazine.