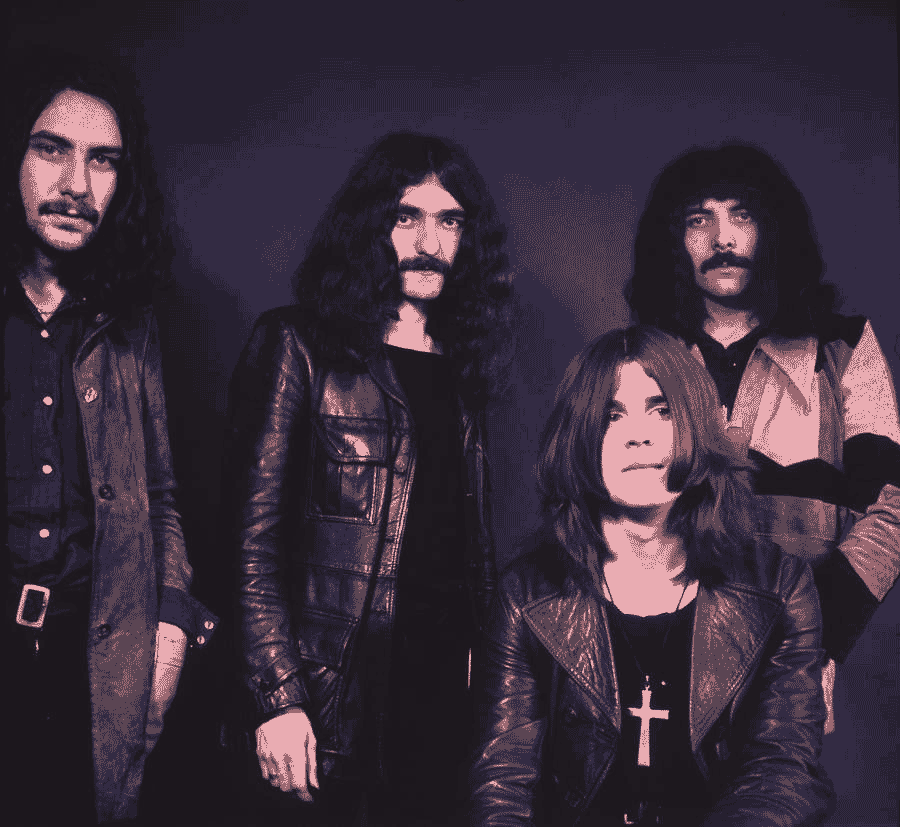

Seattle, March 1972, under a grey gunmetal sky. Black Sabbath are on their biggest US tour yet. Private planes and limos and all their chicks for free. Plus all that blow. Or ‘Charlie’ as they called it back then. Sabbath’s third and most recent album, Master Of Reality, had become their first US Top 10 hit. They were still in their early twenties, and they weren’t even peaking yet. The future was theirs to fuck with.

A hundred shows into an eight-month tour, four nights earlier they had watched Joe Frazier become the first man to beat Muhammed Ali in a boxing ring. Now they were at the Edgewater Inn in Seattle – famous for being built on stilts by the water’s edge, making it an ideal spot for fishing from your hotel room window. The Edgewater was also scene of the now infamous Led Zeppelin ‘mud shark’ episode, where a willing groupie reputedly agreed to be tied-up and pleasured with a fish for the amusement of various wasted band members and roadies.

Every band that stayed there since wanted their own shark adventure. Sabbath singer Ozzy Osbourne took the shark he caught and hauled it into his bathtub, filled it with water, then forgot about it and left for the gig. When he returned several hours later and found the shark dead, he began disemboweling it with a knife, leaving blood and fish entrails all over the walls. Guitarist Tony Iommi, meanwhile, who had also caught a shark, managed to hurl it through Bill Ward’s hotel room window, where it landed on the hapless drummer’s bed. “He was very surprised,” Iommi deadpanned. “Not pleasantly…”

At the end of the US tour the band were given a long weekend off, a three-day gap before flying to Japan for two shows at the Koseinenkin concert hall in Osaka. It’s the venue where Deep Purple would make their Japanese debut three months later, and tape the shows for their legendary live Made In Japan double album. Sabbath could have beaten Purple to it. Except that they were denied entry visas because of their various criminal convictions: Ozzy for theft, Tony and Bill for dope.

The Japanese shows were cancelled, as were dates in Australia. So the band flew home and were glad of the break. On the tour, bassist Terry ‘Geezer’ Butler had been the first to crack, complaining of terminal tiredness, as one show blurred into another.

“The trouble was in them days it wasn’t: ‘Oh, have a few weeks off until you feel better,’” he said, frowning. “It was: ‘Here, have a line of this’ or a smoke of that. ‘Take these pills, they’ll keep you going.’ It was about keeping going on the road. Until one day I knew I’d had enough – and had to stop. The others weren’t happy but there was nothing I could do. I thought: ‘I’m cracking up here,’ you know?”

When Ward was then diagnosed with serum hepatitis, they knew they were in real trouble.

“We were only about twenty-two years old, but we were already pretty much veterans,” Ward told me. “I got serum hepatitis from narcotic abuse. I was jaundiced for months.” Hepatitis B, as it’s also known, is not an infection that can be contracted from casual acquaintance, but a serious virus that is almost always caused by using infected syringes – ‘dirty needles’ – to inject drugs. Until then, Ward said, “I thought I was invincible… I didn’t feel so invincible after that.”

Despite doctors’ warnings, as soon as the jaundice subsided he went straight back into doing what he’d been doing. It was 1972, and that was simply “what you did, what everyone did”. He paused. “I’m pretty lucky to be alive, to be honest.”

With little else to do, Sabbath went to work on their next album. Or rather, Tony did. For the first time since their debut album two years before “took off like a fucking rocket,” as Ozzy put it, they were allowed to take their time. No more albums recorded on the run, between tours. This was the big time, they had a lot to live up to suddenly, and, as with Led Zeppelin’s momentous fourth album, released six months before, a great deal was expected of Sabbath’s fourth album.

Just one snag: a pub less than a mile from their Birmingham rehearsal studio. Most days, after a cursory plod through a few loose jams Iommi would be left to toil alone, after the others had wandered to the pub. Hours later they would return and half-heartedly enquire of their stone-faced leader: “Got anything yet, Tone?”

Iommi began to get the hump. A week into this irksome routine he’d had enough. When it was suggested they continue work on the album in LA, partly as a tax avoidance scheme, partly because studios were cheaper there, Iommi jumped at the idea. The others dragged themselves away from the pub long enough to follow.

Iommi had always been the driver – Osbourne still refers to him as Darth Vader – but now he was a man on a mission. It hurt that, as big as Sabbath were, they were still cold-shouldered by the music press, rarely mentioned in the same breath as more fashionable London-based contemporaries like Zep and Purple. Iommi was going to fix that.

A week later, working in LA on what he had decided would be titled Vol 4, in that portentous 70s way where albums were regarded as the latest almost biblical statement of earnest artistic merit, they were living together in the same luxury Bel Air mansion that quickly became notorious.

They rented it from John Dupont, millionaire scion of the Dupont family, who owned the multinational Dupoint chemicals corporation – key players in America’s development of atomic and chemical weapons, an irony not lost on Butler, the writer of War Pigs and other antinuclear diatribes, but who was too busy snorting mountainous lines of coke to care.

“We were like the fuckin’ Monkees’ evil twins,” Osbourne recalled in his baleful Brummy accent. “Hey hey we’re the-junkies…”

The house came with an Olympic-sized swimming pool, overlooked by an enormous ballroom which the band used to jam in and work on material. Band manager Patrick Meehan also set up office there, along with two French au pair girls. Recording took place at the nearby Record Plant, one of the first state-of-the-art studios to offer rock stars the ‘relaxed’ vibe they worked best in and also the go-to hit factory for high-decibel bands.

It was the perfect environment, Sabbath decided, to produce the album themselves – that is, for Iommi to lavish time and effort on his baby. A loose arrangement that contrived to make the sessions the longest the band had spent on an album (more than two months eventually) and by far the most hectic. What really helped the process along, Iommi would later admit, was “the enormous quantity of coke” the band were now getting through.

“We were all fucked-up bad,” Osbourne recalled. “Dealers coming round every day with cocaine, Demerol, morphine, everything round the fucking house.”

“It became a ritual,” Iommi would tell me. “Every time we’d do an album, we’d get a load of dope and then some coke and whatever else and off we’d go. I never used to want to leave the studio. That’s why we enjoyed making Vol 4 so much, because we had the house, and it was a great vibe we had.”

He pauses, before adding: “It did become insane.”

The cocaine would be delivered in phials in a box disguised as one of their speaker cabinets. It was the strongest, purest cocaine then available anywhere in America. The band would drool with anticipation as huge mounds of the white powder – the ‘snow’ – would be carved out on one of the marble-topped banquet tables, from which the band would take what they wanted, when they wanted, however they wanted – which was a lot.

One night, Osbourne was so stoned he accidentally sat on the button for the alarm, rigged to alert the local police station. As two squad cars screeched to a halt outside and armed cops began banging on the ornate front door, the band freaked out and flushed several ounces of grass and dozens of phials of pharmaceutical cocaine down the mansion’s various toilets.

Convinced they were being busted, “we must have flushed, like, ten thousand dollars’ worth”, Butler recalled. When finally they got one of the au pairs to answer the door and discovered the cops were simply responding to the false alarm, there was another crazy scramble to see if they could unclog any of the toilets and recover their drugs. Too late. Quick, get on the phone… According to Butler, it was also at the house in LA that he and Ozzy first enjoyed LSD.

“I’d done acid in England,” he told me. “Never wanted to do it again. Just had a terrible, really bad experience with it, really bad. The girlfriend I had at the time had to literally lie on top of me to stop me jumping out the window and killing myself. I swore I’d never do it again.

“Then we got to California, and we were at this chick’s place, this massive beach house in Laguna. And she gives us this stuff, psilocybin. I’d never heard of it, didn’t know it was another name for acid, and just took it – me and Ozzy and these girls. Ozzy went for a swim in the ocean [laughing] – at least he thought he did, but he was still on the beach, flailing away in the sand.”

“At that time in America, too, people were very fond of lacing your drinks with acid. I didn’t care,” Osbourne said. “I used to swallow handfuls of tabs at a time. The end of it came when we got back to England. I took ten tabs of acid then went for a walk in a field. I ended up standing there talking to this horse for about an hour. In the end the horse turned round and told me to fuck off. That was it for me…”

Word got round, and Sabbath’s Bel Air pleasure dome became one of the most debauched and therefore trendiest places in LA to hang out. Crowds of drug dealers and groupies and new best mates gathered night and day. So many that the band would make the girls queue outside on the lawn. Getting up and being driven to the studio and working was “the down part,” Ward admitted. Not for Iommi, though, who was spending longer and longer at the studio, as the long cocaine nights flitted by like the lights of a runaway train.

“You’d always read about bands like Deep Purple or The Faces going off playing football together,” he told me. “But we took our music much more serious than that. Or I did, anyway. Once I got in the studio, that was it, I wasn’t coming out again till it was over.”

Despite the mayhem surrounding its genesis, Vol 4 became another stone-cold classic Sabbath album. Opening with the eight-minute-plus epic Wheels Of Confusion, what jumps out is Iommi’s leonine lead guitar, a future-flash step on from the muggy sound of previous album Master Of Reality.

Intent on proving the band’s critics wrong, desperate to somehow catapult Sabbath’s musical credibility into the same starry stratosphere that Zeppelin and The Who now inhabited, the emphasis was on versatility, musicianship, rock’n’roll witchcraft.

Iommi sat down to play piano while Geezer operated the Mellotron on Changes, their most sophisticated ballad yet, and their first fully formed love song. It might have been a US hit single, too, if they had taken the advice of the Warner Bros radio promotion team, but Iommi wasn’t far gone enough yet for that. Keeping with their policy of not releasing more than one single from an album, they plumped instead for Tomorrow’s Dream, a stolid mid-tempo rocker and a great album track – and never a hit single in a million years.

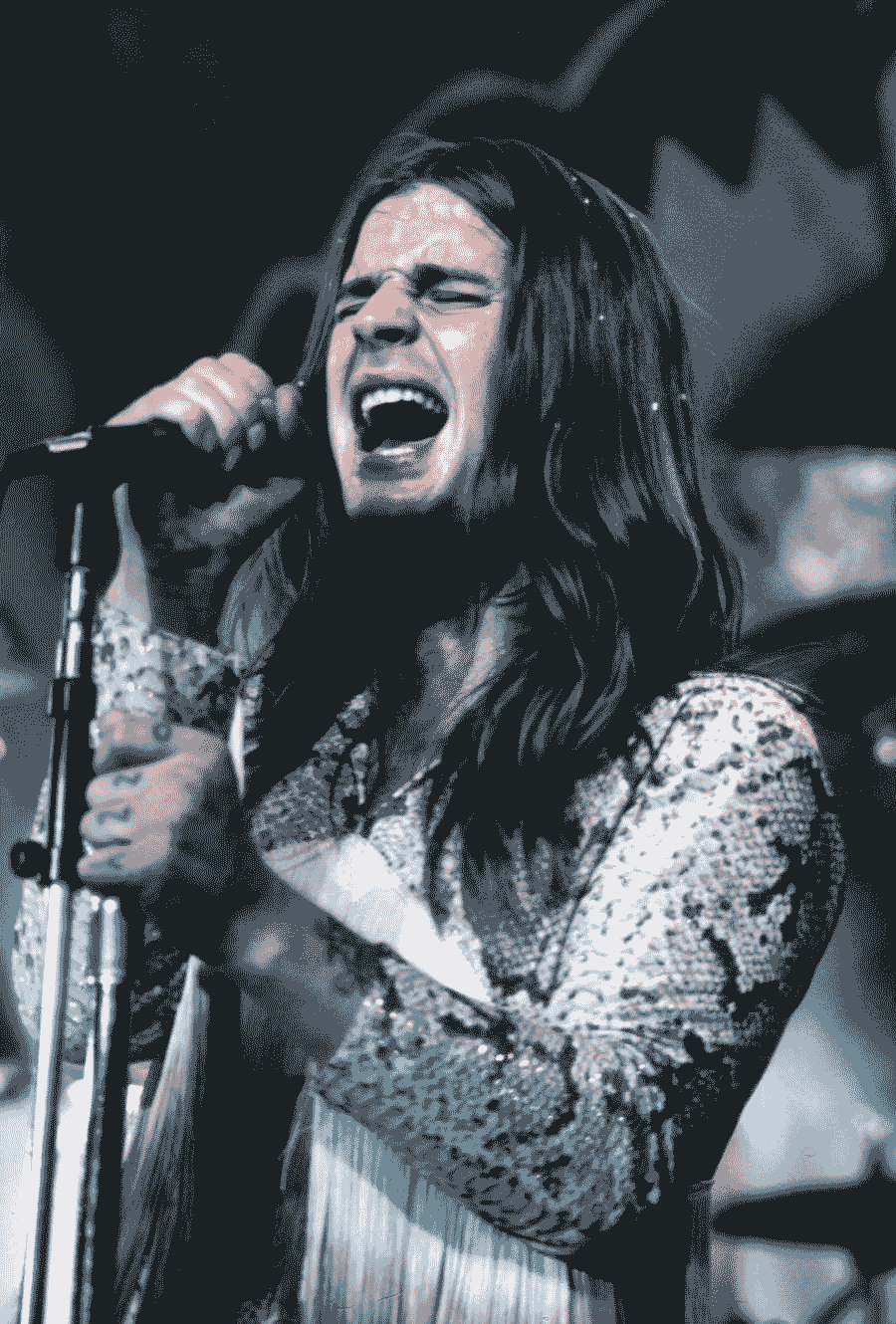

Elsewhere it was First Class all the way. With its ferociously funky rhythm and needle-sharp single-string riff, Supernaut was like a white metal version of Isaac Hayes’s Theme From Shaft, a huge hit the year before, Osbourne’s voice like mercury pouring over the silver spoon of the guitars and drums; Butler’s lyrics, which he now claims to remember very little about writing, yielding to the new era of debauchery the band were now fully embarked on, of wanting to ‘touch the sun’ with the ‘need to fly’. There is not even a guitar solo, just a hail of percussion that takes over halfway through, before finally allowing the twisted riff in again through the back door.

The subject matter – and chief inspiration for an album they would not so subtly thank in the sleeve notes for with the words: “We’d like to thank the great COKE-Cola company of Los Angeles – was addressed even more directly in Snowblind, with Osbourne balefully singing about his dreams being ‘flaked with snow’ as the band pounded down on the juddering rhythm, lashing out the icy riff like a razor blade chopping white lines on a gigantic, cracked mirror.

Again the melodrama is expanded, with the surprise addition of a string quartet over the last minute or so, as Iommi weaves his way through a typically frenzied guitar solo. Even the lighter moments that Iommi always insisted on, as contrast for the frosted darkness of the show stoppers, were somehow more malevolent.

Of the two instrumental interludes, the first, FX, was simply Iommi, fuelled by way too much coke and grass, standing naked in the studio control room, distractedly fiddling with his electric guitar, as if sending signals out to space. Which is in effect exactly what it was, hence its title.

“He took all his clothes off in the studio,” Butler recalled, “and he was hitting on his guitar strings with the crosses that he wore around his neck.”

The second, Laguna Sunrise, came fully formed from his childhood imagination, a lush acoustic instrumental, flamenco in style, accompanied by a soaring, blissfully romantic string section. This was music to watch the Californian sunrise to – but only after you’d been up all night getting wasted on the moon and stars first. There was also another hit-that-never-was in the surprisingly short and catchy St. Vitus Dance, its irresistible tunefulness belied only by the mercilessly brutal chords Iommi stabs each verse with.

The true voice of Vol 4, though, was captured on its finale track, Under The Sun. A perfectly executed bookend, it’s another epic journey track, long, convoluted, and as hard to hold on to as the tail of a tiger. Moving through three discernible musical sections, it was tracks like Under The Sun that would become the sonic signpost for those bands that would follow Sabbath in the years to come; groups like Iron Maiden and Metallica, whose entire careers could be traced virtually to the last two and a half minutes of Under The Sun; self-absorbed, pained, almost repellent in its undeniable magnetism; over-involved and desperately serious; epic right down to its last inglorious, nail-hammering chords.

The final mixes for Vol 4 took place back in London, but of the band only Iommi was there to oversee them. Osbourne had gone back to his first wife Thelma and the family in Birmingham and talked about opening a wine bar. Now a husband and father – although mainly by long distance – he also moved his young family into a new house.

Butler, although also married, was still taking his laundry home for his mum to wash when he finally passed his driving test – and promptly bought a Rolls-Royce, phoning manager Patrick Meehan and getting him to “send a cheque”. Then he bought a house. A big one.

Not be outdone, Ward also bought a Rolls Royce, filling the back seats with crates of cider. Ward was, as he put it to me, “leading a Sid and Nancy lifestyle” with his latest girlfriend, who travelled back with him from LA, “living in hotels [and] loaded all the time”.

“That was the first album where I nearly got kicked out the band,” he said, frowning.

It was one thing for him to be zonked out all the time on cider, dope and cocaine, quite another for him to raise any objections to the “more sophisticated” music, as Iommi saw it, that presented itself on the new album. When Ward suggested they “forget fucking Mellotrons and string quartets and do some blues jams,” Iommi turned on him. After that, said Ward, “there was kind of a cold eeriness in the studios, and I realised I was under the gun”.

When Vol 4 was released, in September ’72, British music press reviews of the album were, again, universally snub-nosed – Max Bell described it in Let It Rock as “a monumental bore”.

In the US, however, the critics seemed to be coming round to Sabbath at last. Even Lester Bangs, who had eviscerated their first two albums, now performed an unabashed about-face, describing Sabbath in Creem as “moralists” and comparing their lyrics to those of Bob Dylan and the books of William Burroughs.

“We have seen the Stooges take on the night ferociously and go tumbling into its maw, and Alice Cooper is currently exploiting it for all it’s worth, turning it into a circus,” Bangs wrote. “But there is only one band that has dealt with it honestly on terms meaningful to vast portions of the audience, not only grappling with it in a mythic structure that’s both personal and universal, but actually managing to prosper as well. That band is Black Sabbath.”

Paradoxically, however, just as the media spotlight was finally swinging their way, Sabbath experienced the first reverse of their career, with Vol 4 getting only as high as No.13 in the US – their lowest chart placing since their first album. In Britain it was a similar story, getting to No.8, the same spot Sabbath had peaked at in 1970.

These days, ironically, Vol 4 is one of the Sabbath albums that mainstream critics cite as their favourite, yet at the time Tony Iommi looked upon it as a comparative failure. He blamed the pressures the band were under to come up with a follow-up to their biggest US hit. He also blamed the rest of the band for, as he saw it, “leaving everything up to me”.

Iommi was determined that their next album would be different. None of which stopped fans flocking to their latest American tour, where Sabbath’s reputation as monolithic doom merchants now preceded them. Sabbath rooled. By the start of the US Vol 4 tour, in the first week of July, they had their own coke dealer travelling with them. “He’d just turn up,” Osbourne said, “and he had a suitcase full of fucking kilos of this shit. Then one day I was in his room, and I opened his bag and there was bags of uncut coke, cut coke, different grade coke. I picked up one of these bags and there was a revolver underneath! I thought: ‘This smells like bad news!’”

That was also the tour, according to Osbourne, that “the groupies knew more about our tour itineraries than we did”. One morning he was awakened by a voice telling him: “I’m the Blow Job Queen. And who are you?” Freaked-out, Osbourne pretended to be Butler and gave her his room number. Ten minutes later Butler was on the phone to Osbourne complaining bitterly that he’d got some crazy chick in his room that he couldn’t get rid of. When he stopped laughing, Osbourne called Iommi and Ward and got them to accompany him to Butler’s room.

“So we all go over and say: ‘Please leave.’ And she says: ‘No! Why? I give the best blow jobs in the west. Don’t you believe me?’ We don’t want to hurt her, we don’t know fucking what to say or do. So finally we all threaten to piss on her if she doesn’t leave, and she does.”

Osbourne looked forlorn. “Gigs, bars, hotels, radio interviews… they were everywhere we went. We suffered the results as well. We got clap, crabs, all sorts of diseases. Then we’d have to go through the cures, big painful shots of penicillin in the arse…”

There would be many more volumes to come in the decades-long Black Sabbath saga, but their 1972 Vol 4 shows were the last shows before the rot set in as a combination of money and drug problems eventually robbed the band of their original spark. For all their misadventures on the road in America, they would never be quite so innocent again.