Drums, death and destruction: the story of Mountain's Corky Laing

Like most young budding rock musicians, Corky Laing had a dream. Unlike most, his came true, as he steadily scaled the rock’n’roll mountain and made it to the very top

The entire course of Corky Laing’s life was changed by a power cut. A little over 50 years ago, in the summer of 1969, the drummer and his band Energy were playing a gig at a beach hut in Nantucket, a small island off the coast of Massachusetts.

With the entire population having cranked up their air conditioning, the power supply crashed suddenly at half-past midnight. Energy had been firing up the room and nobody wanted the show to stop – especially Corky.

“I was hyped on soul pills. I had been unable to take my eyes off a gorgeous southern babe called Molly who was wearing a see-through, skin-tight dress covered in flowers,” he recalls today. That Molly was dancing with Roy Bailey, a friend of Laing’s, seemed irrelevant.

“She was grinding and humping and I was thumping and staring,” he says with a smile. “When the juice went out there was no way that I would stop and lose Molly on the dance floor.”

Almost as if guided by some external force, Laing began smashing away at a cowbell over and over again, and at the top his lungs bellowing out the words: “Mississippi queen, do you know what I mean? Do you know whatI mean?”

As the dancing began again, the eyes of Corky and Molly locked together and nobody left the room. Laing swears that his primal, rhythmic chat-up line lasted for more than an hour before a generator kicked into life and sufficient power to fire up the band again was restored.

To Laing’s great disappointment, Molly didn’t leave on his arm on that night, and instead remained with Bailey (who in years to come would draw the whale on the cover of Mountain’s album Nantucket Sleighride).

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Apart from the incident leaving Corky with a small long-term injury, try as he might, he just couldn’t get the events of the night before out of his head. So he put the kernel of a song idea on tape. Of course, he had no inkling that it would eventually be the basis of a classic rock song.

“After screaming so loudly and for so long that night, I gave myself chronic laryngitis, and it screwed up my voice forever,” Laing says today, before adding with a contented smile: “It was worth it.”

The youngest in a family of five children, Laurence Gordon Laing was raised in Montreal. The name ‘Corky’ was born when his siblings struggled to pronounce either of his given names. Energy was Laing’s first band of genuine note. Living in Montreal would prove a helpful stepping stone in his intended vocation as a drummer.

During the late 1960s, British bands often had the Eastern Canadian cities of Montreal, Ottawa and Toronto as first stops on their North American tours. The reason for this was twofold: it enabled them to secure visas and also perform warm-up shows away from the US media’s watching eyes.

Energy were managed by the same family that promoted gigs at the Montreal Forum, and were conveniently placed to secure prime opening spots to some of the biggest names of the era, including the Rolling Stones and The Who.

It was at the latter’s performance at the local hockey arena that Laing almost got his face caved in by Keith Moon. At the Who show, Laing stumbled upon their drummer Moon’s sequined Union Jack coat unguarded underneath the stage. Almost without thinking about his actions, Laing picked up the iconic garment, realised that it would fit him, and whisked it away to Energy’s dressing room.

When Moon realised it had gone, he was not happy. “I could hear the yelling from the room next door,” Corky recalls, lapsing into a Dick Van Dykestyle impersonation of a cockney: “‘Me jacket! Where’s me jacket? Me grandma made it for me and I left it under the stage. I can’t believe it’s gone!’”

Corky’s conscience was pricked. Entering The Who’s dressing room with the coat, he saw a naked Moon beside himself with dismay. That quickly turned to joy as the garment was returned to him

“‘Me jacket! You’re a gentleman! I can’t believe you’ve got me jacket!’ and he gave me a big kiss right on the lips,” Laing recalls. “I could almost feel his tongue.”

And then Corky did something very foolish.

“Without thinking I told Keith: ‘I was going to steal it.’ And suddenly you could hear a pin drop in the dressing room.”

Understandably, Laing’s heart was in his mouth when the notorious Moon The Loon rushed forward, grabbed him in an embrace and said: “But ya didn’t, mate, did ya? Ya didn’t!” Still stunned, Laing was rewarded with another kiss.

“Keith kept blowing me kisses as he walked away down the corridor with cries of: ‘I love ya, mate. I’ll never forget ya,’” Corky says, “and I’m happy that Keith and I remained good friends.”

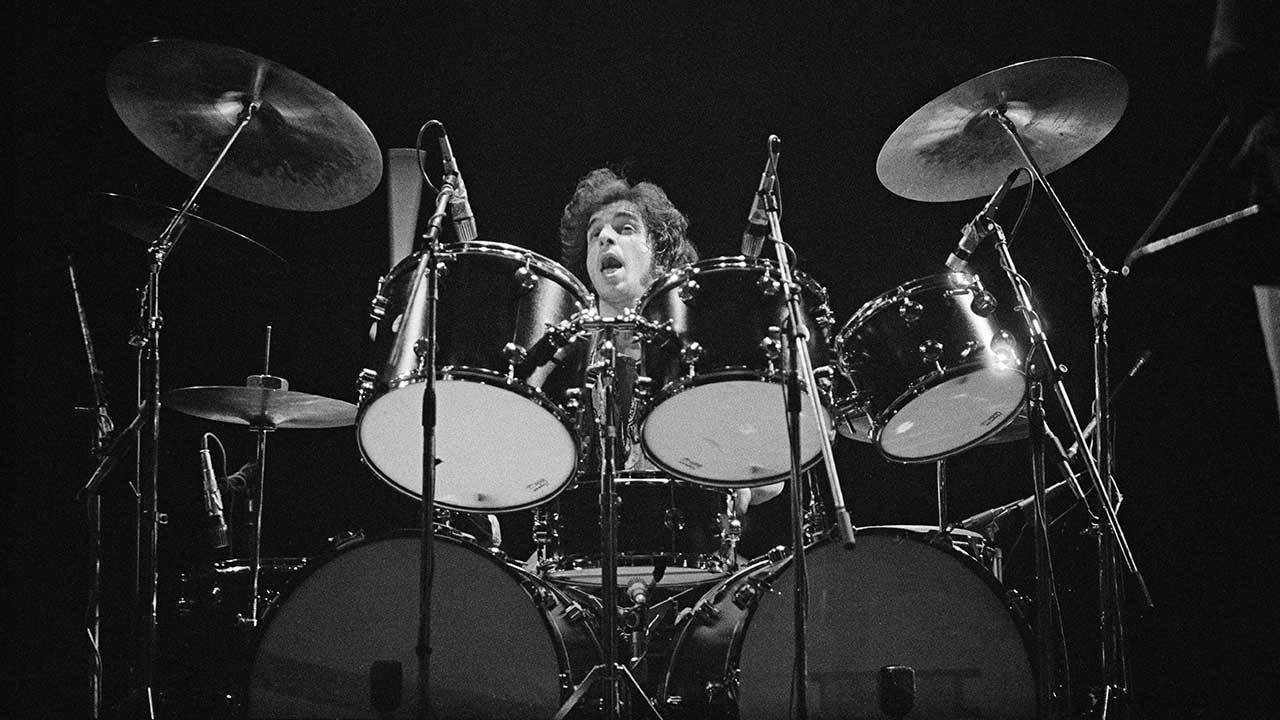

More importantly, Moon became a musical inspiration for Laing, who modelled his own extraordinary technique on that of The Who’s eye-catching drummer. Among the lessons Moonie taught the willing apprentice was to keep his cymbals low in order to maximise views of the cleavage in the front rows of the audience.

“Keith played drums with style, passion and such an incredible sense of joy and commitment,” Laing explains now. “I would like to think it rubbed off. To this day there isn’t a part of me that doesn’t try to imitate him when I’m playing on stage.”

Laing was never backwards in coming forwards, and when John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s bed-in tour arrived in Montreal in 1969, the budding musician could not resist turning up at their hotel armed with a fake press ID in an ostentatious attempt to gain entry to the pair’s suite.

Incredibly, the ploy paid off. It was only when the 20-year-old was presented bed-side that both bravado and game plan deserted him, and he told the couple: “I’m very sorry, but I’m not a newspaper writer, I’m just a musician in a local band that would do anything to meet you. I’ll just leave.”

Equally amazing, Lennon invited the trembling youth to sit down and tell his story. Lennon loved the band name Energy, and he and Laing shared a few minutes talking about songs and writing. As Laing prepared to leave, Lennon told him: “You have a set of balls, Mr Energy”.

The incident would draw laughs several years later, when Laing, now a star in his own right, sang backing vocals on Lennon’s 1975 album Rock ‘N’ Roll.

To Energy’s great joy, they were chosen as willing guinea pigs to accompany the musician Felix Pappalardi in an audition for a position as a producer for Atlantic Records, and went to New York in 1967 to a record a version of Nat King Cole’s ballad When I Fall In Love. Pappalardi got the gig, and would go on to produce Cream.

In the summer of ’69, in an act of blind faith, Energy threw caution to the wind and moved to New York City. They very quickly realised the scale of the challenge they faced. Mountain bassist Pappalardi had made a mental note of Laing’s name, and when the band were looking for a drummer to replace the outgoing ND Smart, Laing received a call.

And so he was then was left with a difficult decision: turning down the opportunity to join a group with genuine prospects – that August, Mountain had appeared at Woodstock – or remaining loyal to bassist George Gardos and singer/ organist Gary Ship, the friends with whom he’d made such a leap of faith. With mixed feelings he let his head rule his heart.

On September 12, 1969, Laing’s first day as a member of Mountain, Bud Prager (the manager who would be the brains behind the rise of Foreigner) warned the rookie: “Felix will push you real hard, he is going to need a hundred and fifty per cent from you.”

If anything, Prager undersold the situation.

“Felix was a dictator – he was hardcore,” Laing remembers. “For a long time he and I were not friends. But in a way that was fine, as my experiences with Felix set me up for what would later happen when I worked with Jack [Bruce]. They were two of the best teachers in the whole wide world.”

The other two members of Energy had declined to work the basic idea of the jam from the power cut evening into a bona fide song. But when Mountain were looking for a final track for their album, West spotted its potential right away.

“Within ten minutes, Leslie had this guitar lick and was screaming out the lyrics,” Laing says, smiling at the memory. When Mountain recorded the song at the Record Plant in New York, Laing had used a cowbell as a backing track accompaniment, and upon its completion assumed that producer Pappalardi would take it out during the mixing stages. “But Felix went: ‘No, I think it’s kinda cool’, so the cowbell stayed.”

Jimi Hendrix and his Band Of Gypsys were in the studio next door at the Record Plant. Mountain wanted Jimi to be the first person to hear their new song.

“I had hung out with Hendrix before, so Felix and Les asked me to invite him in,” says Laing. “As we played him the final mix, his head sunk further and further downwards. Finally, he looked up and told us simply: ‘Cool.’ But the way he said it, we knew we had something special.”

To this day there isn’t a part of me that doesn’t try to imitate Keith Moon when I’m playing on stage

Corky Laing

Released in March 1970, Mountain’s debut album, Climbing!, was a followup to guitarist Leslie West’s solo album, Mountain, from the previous summer. A thoughtful yet hard-hitting piece of work, the rumbling, sonorous strains of Climbing! are often credited with contributing towards the birth of heavy metal.

“The reasons for its success were the musicality of Felix Pappalardi versus the playing of Leslie West, which came straight from the gut. Those guys were complete opposites,” Laing muses. “My contribution is a little harder to define, but I consider myself the Henry Kissinger of rock’n’roll – it was my job to maintain the lines of communication.

“And let’s not forget Steve Knight, who was one of the most peace-loving guys you’ll ever meet,” he adds, referring to the keyboard player who spent three years with the band. “But Mountain was all about finding middle ground between the spontaneity of Leslie, whose guitar had incredible tone, and the beautiful lyrics and writing of Felix, who loved to tell stories like Nantucket Sleighride [about the sinking of a boat that harpooned a whale] with his songs. Let me tell you, though, it wasn’t a pretty band.”

Now a half-century old, Climbing! still holds up marvellously, and Laing remains justifiably proud of his co-writes Never In My Life, Sitting On A Rainbow and For Yasgur’s Farm, the latter having begun life as an Energy song called Who Am I But You And The Sun, but which at Felix’s instigation had the title changed to honour the farmer who allowed his land to be used for the Woodstock Festival.

Although Laing joined Mountain several months too late to have played with them at Woodstock, he retains a pub-quiz-style connection with the event which attracted a reported half a million people and crowned the era of psychedelic rock music.

While Mountain were at the Record Plant, Laing was asked to patch up a recording made by Ten Years After intended for the Woodstock film soundtrack album.

“A mic on Ric’s [TYA drummer Ric Lee] drums had failed [during the recording at the festival], and I had to re-record his parts to I’m Going Home,” he relates, grinning. “I didn’t even know who Ten Years After was, let alone how their song went. I’m Going Home was twenty-nine minutes long [It’s actually less than 10 minutes – Ed] and [guitarist] Alvin Lee kept speeding up and slowing down, so it was quite a challenge.

"But they were thrilled with what I did. They didn’t pay me, but a month or two later I was sent a gold record. And then a week after I received another disc for For Yasgur’s Farm having been on the live record. So I ended up receiving two gold records for a festival that I didn’t even fucking attend!”

Mountain were very soon sucked into a world that involved private planes, fancy hotel suites and the realisation of their every wish. Having started out on dope, cocaine and then heroin became the group’s recreational substance of choice. A novice at such matters, Laing still recalls sharing something illicit with Jimi Hendrix at the Fillmore East in 1970.

“He had a tiny sterling silver bottle of something he called magic dust, and asked whether I’d like a taste,” Laing says, smiling at the memory, “and I wasn’t about to say no to Jimi.”

Drugs would ultimately set Mountain on the path to destruction, the situation worsened by the escalating egos and the band’s already complex inter-personal relationships. The presence of Gail Collins, Felix’s wife who had written lyrics for both Mountain and Cream, in their midst only made things more confusing.

“The first time I met Gail she said she wanted to be my ‘old lady’ – she was coming on to me. But I had never heard the term ‘old lady’ before. I thought she was Felix’s mother,” he recalls in horrified tones.

After Mountain drew to a close with 1971’s half-live/half-studio album Flowers Of Evil, West and Laing formed a new power trio with ex-Cream bass player/singer Jack Bruce. These were the days of ‘superbands’ – or as Laing jokingly prefers to call them, “stupor-bands”.

Despite the negative influence of clashing managers, Prager and Gary Kurfirst representing Leslie and Corky, Robert Stigwood looking after Jack, West, Bruce & Laing made two respectably received studio records – Why Dontcha and Whatever Turns You On (released in ’72 and ’73, respectively) – before the following year’s swansong live set Live ‘N’ Kicking.

“Jack blamed us [him and West] for the break-up of West, Bruce & Laing, but that’s untrue,” Laing states now. And the facts seem to back up his view; Bruce being registered as drug user prevented him from setting foot in the States, so the band was effectively doomed.

“The dates [in America] were booked with all of the biggest promoters, and then two weeks before they were set to start we were told he couldn’t go,” Laing recalls. “Working with Jack ranks among the biggest joys of my life, but it was also among the most challenging things I ever did."

Although Laing and West continued briefly as Leslie West’s Wild West Show, in 1974 West and Pappalardi assemble a new-look Mountain and released the double live album Twin Peaks. Laing rejoined them for the same year’s Avalanche, but now the band was even more highly charged than before. When Laing dared to suggest bringing in an outside producer, due to Pappalardi’s failing hearing caused by Mountain’s notoriously high-volume concerts, without warning Felix punched him full in the face.

“It [the Mountain reunion] was a desperate act,” admits Laing, who needed what he has since termed “a cooling off period”.

His growing relevance as a performer was reflected by a solo album, 1977’s Makin’ It On The Street, which featured an impressive array of friends and contemporaries including Eric Clapton, Dickey Betts of the Allman Brothers Band and Randall Bramblett. Although the sales it deserved didn’t materialise, the album became a cult favourite.

Suitably enthused, Elektra Records commissioned a follow-up. With Pink Floyd producer Bob Ezrin on board (until he was summoned to do The Wall), Laing was joined by West and Pappalardi, Ian Hunter, Mick Ronson, Andy Fraser from Free (who didn’t hang around long enough to record), Todd Rundgren and John Sebastian. But, to Laing’s dismay, with the industry taking a long, hard look at itself with the arrival of punk, Elektra then decided to shelve the results.

The tracks finally got a release 21 years later with the title The Secret Sessions, with the tracks by Clapton and Betts from its predecessor bolted on for good measure (the album was also re-released on vinyl in 2018).

“That record had taken years to make, all kinds of musicians stopped by to jam, each of them was a friend,” Laing sighs. “I still believe that the music stood up, and the positive reviews reflect that belief. But [when it was mothballed] I was heartbroken. That was a very dark time for me.”

It was only going to get worse. By the time Mountain (now with Mark Clarke on bass) released their next studio album, Go For Your Life, in 1985, Pappalardi had been dead for almost two years, having been shot in the neck by his wife Gail Collins.

That incident came as no real surprise to Laing, given that Gail had already pulled a gun on Francy, Corky’s wife of the era. In court, Collins claimed ignorance of how to use the Derringer pistol – which, in a twist of irony, had been bought for her as a gift by Felix a few months earlier – insisting that the weapon was discharged by accident. She was charged with second-degree murder and criminally negligent homicide.

“Gail had propositioned me many times, and turning her down was among the better things that I did in my life,” Corky states now. Although it cannot be proven, now that Felix and Gail are both are dead, Laing’s firm belief is that the pair’s marriage had run its course, and on the night he was shot by Gail, Felix had told her that he was leaving her for another woman.

“Leslie has often compared Gail to Yoko Ono, but she was far worse than that,” Corky sighs wearily. “She was quite a witch.”

The touring for Go For Your Life included a spot at Deep Purple’s comeback gig at Knebworth Park in June 1985. After Mountain’s set, they asked around backstage why Nantucket Sleighride had brought such a huge cheer. They were unaware that a clip of the track had been used for many years as the theme tune to the current affairs TV show Weekend World in the UK. “We had no clue!” Laing says.

After West and Laing fell out again, Laing formed the group The Mix, followed by Cork which featured Noel Redding from the Jimi Hendrix Experience and Eric Schenkman of the Spin Doctors. After Laing had played with Meat Loaf for a while, in a gamekeeper-turns-poacher move he cut his hair for his new role as A&R vice president of PolyGram Records in Canada from 1989 to ’95.

“Yeah, I became a weasel,” he says, laughing at the memory. “It was the twilight of the golden years of the record industry, and I caught the last waves. I had already realised that the record companies were going to go bust, but although it was a very different job for me I enjoyed it.”

In 1992, West and Laing buried the hatchet to work together in promoting a two-disc Mountain anthology called Over The Top. That led to the first Mountain album in a decade, Man’s World, followed by Mystic Fire and, somewhat bizarrely, in 2007 a collection of Bob Dylan covers titled Masters Of War, with guest appearances from Ozzy Osbourne and Gov’t Mule guitarist Warren Haynes.

The band haven’t performed live since 2010. In 2011, West, by now stricken with type-2 diabetes, brought on in part by the days in the 70s when he tipped the scales at more than 21 stones (130 kilos), had his right leg amputated below the knee to prevent a foot infection from spreading into his body. Although he continues to make solo records, there is now very little communication between him and Laing, especially since a disagreement over the rights to Mississippi Queen.

“What happened in our last year together was that Leslie really stopped caring – all you need to do is go on to YouTube for proof,” Laing sighs. “I really wish that wasn’t so, but it’s pretty pathetic.”

For the past couple of years Laing has continued to work within the format of a power-trio under the name Corky Laing’s Mountain. The line-up is completed by Chris Shutters on guitar, and bassist/vocalist Mark Mikel.

“I’ve been through fifty years’ worth of musicians, and I’m not going to lie and tell you that all of them were great,” he volunteers, “but these guys really nail it.”

Warren Haynes played a part in a simplification of the Mountain sound, pointing out that during Leslie and Corky’s autumn years together too much jamming had gone on. And when Haynes bemoans excessive improvisation, then you know there’s a problem.

“Warren is a huge Mountain fan, and he told me: ‘The way you and Leslie play those songs, I don’t even fucking recognise them any more.’” Corky relates. “‘You jam out so much that you forget to play the fucking songs’. He was right, and I decided that if we are to play Mountain tunes, let’s do them the way the crowd remember them."

Together with Shutters and Mikel, who are both accomplished vocalists, Laing has recorded a new album called The Toledo Sessions, on which tracks such as The Road Goes On and Knock Me Over doff their cap at Mountain’s signature sound.

“Yes, we were striving to capture that vibe,” he enthuses. As we enter 2020, a half-century after the release of Mountain’s Climbing!, Laing’s ultimate goal is to keep Mountain’s songs alive.

“It’s very important to maintain that legacy,” he affirms. “My current band and I have played so many gigs these past few years, and I can put my hand on my heart and tell you that nobody came up to me and asked: ‘Where’s Leslie?’ Not one single person.”

Nevertheless, Laing has decided to be billed as a solo artist when promoting The Toledo Sessions at a show scheduled for London's 100 Club in November. He isn’t fooling himself; he acknowledges that attendances on the last two UK tours when billed as Corky Laing’s Mountain can only be described as ‘modest’, but that fact won’t dissuade him.

“That’s a bit of a pisser, but I’ve got to put it at the back of my head,” he says with a shrug. “I know I don’t have a Lady Gaga-sized following, but the music business as I once knew it no longer exists, and at my age [he turned 72 in January] this feels like starting a new career. I have supreme confidence in the repertoire. The cheers of the crowd, whether it’s fifty people or five thousand people, are all I need to hear.”

With the deaths and/or retirements of so many of music’s biggest stars, and the huge impact of downloading on record sales, today Corky Laing reluctantly owns up to a fear over rock music’s long-term future.

“In my view it’s over already. This is probably the last wave of rock’n’roll – in fact it died a while back,” he offers, sadly. “Most of my contemporaries are either dirt-napping, broke or no longer have the ability or the inclination. But not me. I will continue doing this because I still love it. I’m in music; I’m not in the music business.”

Corky Laing's autobiography Letters To Sarah is available from Amazon.

Dave Ling was a co-founder of Classic Rock magazine. His words have appeared in a variety of music publications, including RAW, Kerrang!, Metal Hammer, Prog, Rock Candy, Fireworks and Sounds. Dave’s life was shaped in 1974 through the purchase of a copy of Sweet’s album ‘Sweet Fanny Adams’, along with early gig experiences from Status Quo, Rush, Iron Maiden, AC/DC, Yes and Queen. As a lifelong season ticket holder of Crystal Palace FC, he is completely incapable of uttering the word ‘Br***ton’.