Imagine metal without makeup. One is a tangible medium – gunk for enhancing, hiding or modifying external features; the other, a noise, a state of mind, a way of life. Throughout history, one has been traditionally associated with the pursuit of female beauty, while the other concerned itself with the pursuit of beautiful females.

Makeup is what allowed some the most iconic and recognisable looks in metal to be created – whether it was there to enhance masculinity in the cock rock days, or as an expression of identity and vulnerability in various subgenres. But what does it mean to be androgynous? Were Kiss’, Poison’s, Mötley Crüe’s or Twisted Sister’s painted faces simply characters for a show, or the place where gender barriers in rock began to break down, one eyeliner wand at a time?

In the early days, there was no ambiguity about the gender identity of the men under the makeup. “Glam metal was determinedly heterosexual, while glam rock deliberately blurred gender and sexuality,” says veteran music journalist Simon Price. “I don’t think glam metal did much in terms of advancing non-conformity.

But, in the context of a country as socially conservative as America, it was maybe a baby-step in the right direction. One shift I did think was interesting was that it heralded the arrival of the ‘male slut’, which is subtly different from the prevailing idea of ‘the stud’.

Glam metal boys presented themselves as ‘tarts’, there to be used, as opposed to rampant stallions out to fuck everything that moved. They invited the female (or even male) gaze, and encouraged their own objectification. They all took mockery in the press for being effeminate, though, which is probably why they went overboard asserting their masculinity in songs.”

There was also an element of pisstakery – Nikki Sixx claims in The Heroin Diaries that Aerosmith’s Dude Looks Like A Lady was inspired by Vince Neil’s effeminate appearance, while Vince has said it came about after he and Steven Tyler went to a bar where all the waiters dressed in drag. Whoever the lady-dude was who inspired the song, he was a trope of the time rather than a pioneer of gender fluidity.

Imagine a young rock fan growing up in the ‘80s, feeling like they couldn’t comfortably align with their assigned gender, and looking for a figurehead to confirm the way they were feeling was okay. Of course, there was Bowie, and queercore and riot grrrl later in the punk scene, but in metal? Not so much.

There was plenty of room for visual experimentation, but lyrically, it was all about the power of the penis. But rather than berate it for being nothing more than Max Factor sponsored by big, hairy man-balls, we should be glad it provided a foundation for experimentation.

Of course transphobia, homophobia and prejudice exists in metal, and it fucking stinks, but there’s always been hope, even if it started on a very superficial level. If you were a guy or girl who wanted to look different to how society said you should, hair metal said that was cool. If you wanted to look that way because the idea of being a guy or a girl in the most basic sense of the words didn’t appeal to you, hair metal offered a visual solution.

“I wouldn’t put a negative spin on it. I prefer to see identities as freely available to anyone who wants to take them,” adds Price. “Rock ‘n’ roll is theatre, and a mask can tell a better story than a face.” That mask – the panda eyes and painted nails that said yes, I am different, and I am proud – was, and still is, worn by fans as a badge of honour.

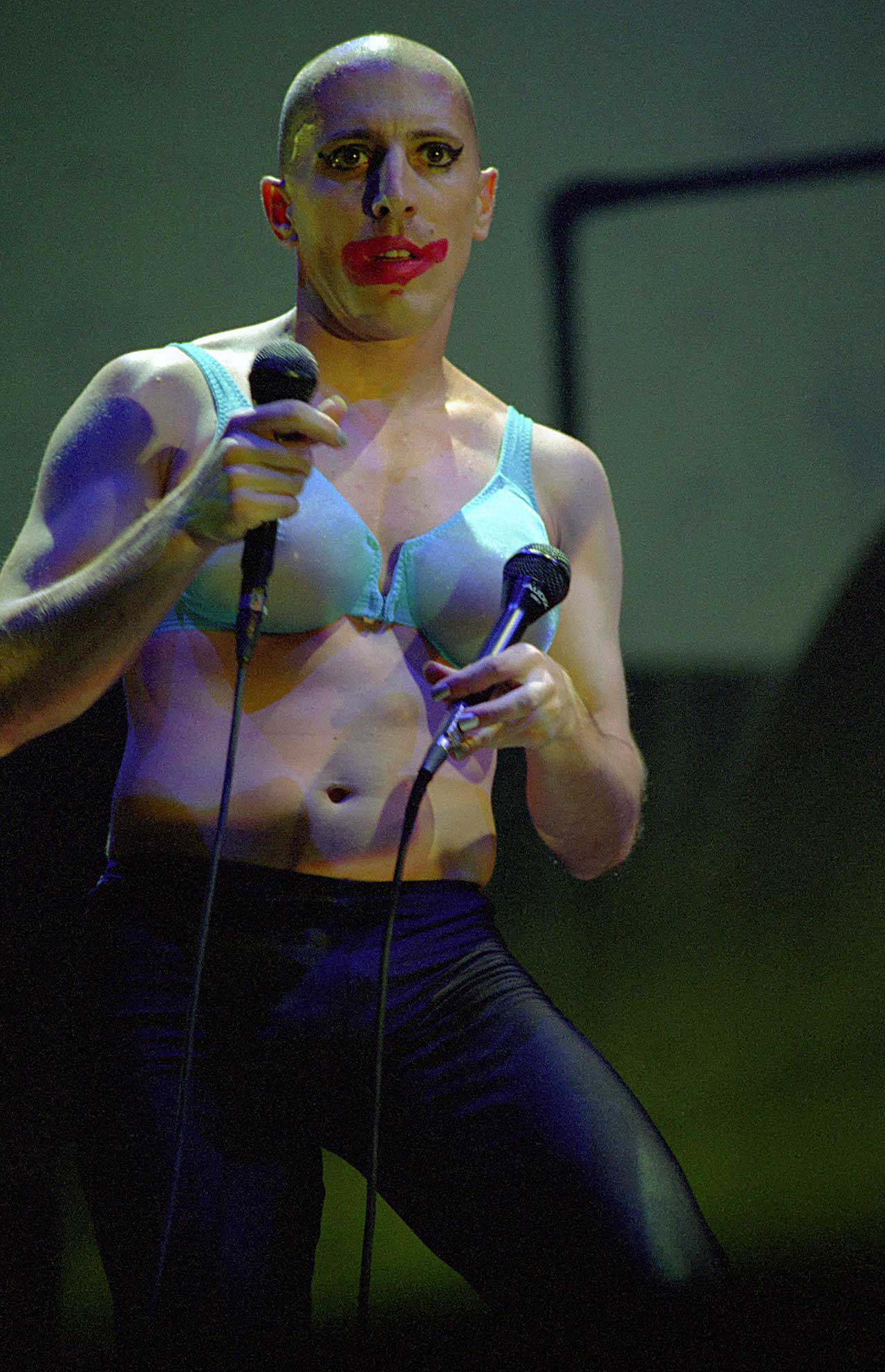

In metal’s numerous subgenres, plenty of musicians have reclaimed androgyny as an expression of their inner self, as opposed to an enhancement of their external assets. As far away from hair metal as you can get is Maynard Keenan; when he wore a plain white bra paired with smudged eyeliner on stage, it wasn’t to present as an irresistible sex object.

Lyrically, he often visits the darker side of sexuality, and his dishevelled androgyny perfectly matched his songs. He might have appeared in a few ‘worst-dressed rockstar’ roundups when music sites needed some #content but largely, to fans, he’s just Maynard and that’s his thing.

Similarly, occasional tutu wearer Billie Joe Armstrong shocked nobody in 1997 when Green Day unleashed King For A Day – a song explicitly about cross-dressing – and it’s become a live favourite with its accompanying madcap visuals.

The idea of cross-dressing wasn’t a shameful secret – it was just something the song’s protagonist enjoyed doing, and his dad was the villain for “throwing him in therapy.”

Over in emo, Gerard Way’s smoky red eyes were a symbol of his internal struggles, which he opened up about in a Reddit AMA in 2014. “I have always been extremely sensitive to those that have gender identity issues as I feel like I have gone through it as well, if even on a smaller scale,” he said.

“I have always identified a fair amount with the female gender, and began at a certain point in MCR to express this through my look and performance style.”

When Life Of Agony frontwoman Mina Caputo (formerly Keith) came out as transgender in 2011, the metal community was largely supportive, and they again rallied around Against Me!’s Laura Jane Grace, who announced she was transgender the following year.

It goes without saying that expressing gender identity through appearance is not, in any way, similar to a straight man wearing makeup on stage, but the fact that gender-blurring aesthetics have always been present in rock could have gone some way towards the scene’s mostly unquestioning acceptance of Mina and Laura Jane.

These two may be the most well-known advocates of trans identity in rock, but they’re not the only ones; Project Armageddon, a Texas doom band, is fronted by trans woman Alexis Hoillada, who was nominated as Best Female Vocalist in Houston Press’s 2013 Music Awards, and Australian outfit Mechanical Black’s first album was a concept record about gender identity.

As well as being an important tool for expressing identity, a carefully cultivated image is also a way to connect with fans. Andy Biersack and Chris Motionless are two of the most ubiquitous makeup wearers in the young metal scene, and the latter’s Instagram is full of pictures of him sporting different shades of lipstick and eyeshadow, with his favourite brands hashtagged underneath.

He’s inspired hundred of YouTube makeup tutorials, and a large proportion of the crowd – male and female – at both bands’ shows paint their faces in the style of the frontmen. Makeup is a blanket of belonging among fans; a gang of Chris or Andy doppelgangers convening en masse outside a music venue might look like inverted conformity, but if it makes them feel good about themselves, so what?

“Nu-metal at the end of the ‘90s brought a lot of boneheaded macho attitude into metal, and it’s never really gone away. So much metal is about what academics would call ‘Performing Masculinity’,” says Price. Makeup is just one way musicians and fans can rebel against the ‘bonehead’ trope; beauty may be skin deep, but its ability to empower goes much deeper.