In the annals of 20th century history, Sunday September 18, 1983, will go down as being about as uneventful as it gets. In the Caribbean, the islands of St Kitts and Nevis finally gained their independence after two centuries of British rule. In Alaska, long-distance walker George Meegan completed a six-year-trek that took him from one end of the Western Hemisphere to the other. Across America, transistor radios rattled and legwarmers twitched to Michael Sembello’s dancefloor ‘smash’ Maniac, the Number 1 single in the Billboard charts.

Only in a small studio deep in the bowels of MTV’s New York HQ was something monumental happening. There, the four members of Kiss – those pansticked titans of glitter-metal – were about reveal their faces to the world for the first time in their 10-year-career. Stripped of warpaint and free of flashbombs, and under unforgiving studio lights, these great American icons of the last 20 years were ready for their close-up.

Watch the footage on YouTube now, and it’s a strangely solemn experience. In the hushed studio, MTV ‘VJ’ JJ Jackson introduces the band in a fathomlessly deep voice, as, one by one, images of each of them flash on screen. First up is Vinnie Vincent (“Lead guitarist and co-writer of many of the songs on the current Kiss album,” intones Jackson with near-Biblical gravitas). Then drummer Eric Carr (“He has been with the band since 1979, and Kiss is, by the way, the very first band that Eric has ever been with”). Then it’s the turn of Paul Stanley (“Lead vocalist and rhythm guitarist and co-founder of the group.”) Finally, Gene Simmons (“Bass, also co-founder of Kiss, he is the fire-breathing, blood spitting monster of Kiss”).

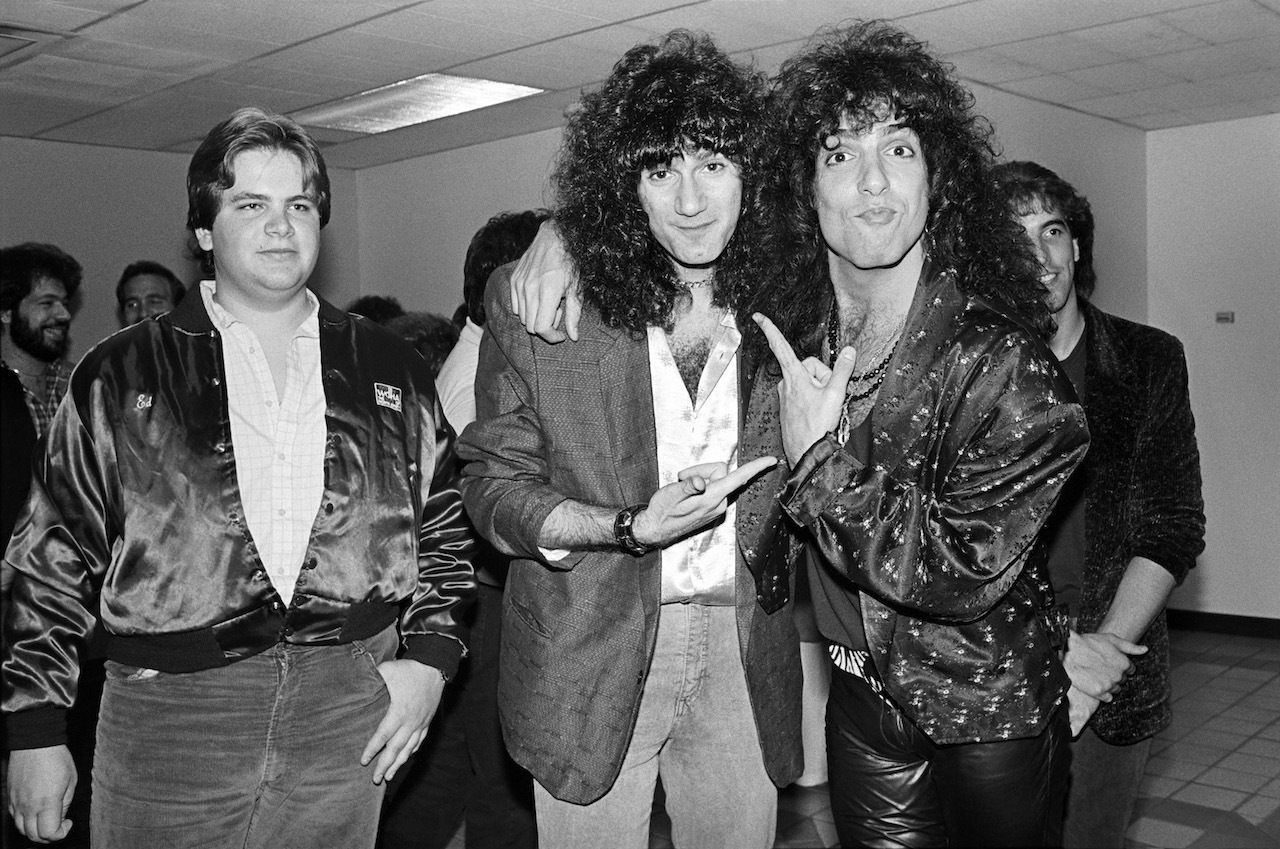

At each beat, the shot of the made-up band member vanishes, replaced by an image of them live from the studio floor: Vincent looking vacant, Carr coquettish, Stanley glowering, Simmons smirking. This, ladies and gentlemen and creatures of the night, is Kiss as naked as the day they were born.

This was a very different kind of theatrics from the band who made their name as rock’s grease-painted Gods Of Thunder. But for all the hooplah, it was been born out of necessity. The huge successes of the 70s were an increasingly distant memory, and the failure of their most recent albums had found them floundering in a new musical world, unsure of who they were and where they were going. Taking off the make-up was the very last (space) ace up their sleeve. This was make or break.

“It had really run its course,” says Paul Stanley today. “It was no longer the original images. We had a fox and we had an Egyptian guy. Maybe next we’d have Turtle Boy. It was becoming farcical. We needed to take a stand. If we were good enough and viable enough as a band, we would survive. And if not, we would meet the extinction we deserved.”

Kiss’s grand unmasking would be a tipping point in the most torrid decade of their career. Before it, they were heading platform boot-ward towards extinction. Afterwards, they slowly but surely regained their status as one of America’s pre-eminent rock’n’roll bands with a canon of towering 80s records that stood steel-clawed toecap to steel-clawed toecap with everything they’d done before and helped lead MTV’s rock revolution. Sure, albums like Lick It Up and Asylum might not have had the boot-in-the-balls impact of their 70s heyday, but at its very best, their 80s output stands among the finest melodic rock that the era produced. And it was made as Paul Stanley and Gene Simmons were fighting for the very soul of Kiss.

“We became victims of our own fame,” says Stanley now. “We lost the hunger, lost the passion, lost focus. We became more concerned with trying to get the approval of our peers as opposed to maintaining our connection to the fans. We became swallowed up by our success.”

Gene Simmons puts it more bluntly.

“For me,” says the sometime God Of Thunder, “the 80s was miserable.”

Kiss had exited the 70s on a high, at least professionally. The disco dust-sprinkled I Was Made For Loving You had given them one of their biggest hits, albeit to the disgust of some of their rockier fans who saw it – quite rightly – as a shameless attempt to keep up with the times.

As Paul Stanley steeled himself to enter the new decade, he had a lot on his mind. “There was a reorganizing of my thoughts about what the band was and what it would be,” he says now. “I quickly went from thinking that this was the four musketeers, that it was all for one and one for all to, ‘What do we do now?’. When certain people aren’t pulling their weight and sabotaging what you want to do. In plain English, just wanting to fuck things up.”

“Both Ace Frehley and Peter Criss wanted to leave the band,” says Gene Simmons, cutting to the chase. “And the manager decided that we should do solo records to keep the band together: ‘They’re solo records, but they’ll be Kiss records too – you’ll have your cake and eat it.’ Ace and Peter, fucking idiots to this day, poor guys.”

In theory, the ploy of releasing four sonically schizophrenic solo records on the same day in 1978 should have been a stroke of genius. Instead, it backfired massively, with each record shifting a fraction of what a regular Kiss record would normally sell and leaving the band facing a serious rethink as they entered New York’s Electric Ladyland Studio to record their next album as a group, Dynasty. “You have to start saying, ‘What now?’,” says Stanley. “And it became real clear that we couldn’t stop the band for one person. Certainly, my love of the band wasn’t going to allow it to stop.”

They didn’t know it at the time, but Dynasty would become the band’s most controversial album yet. In an attempt to cut ties with the past and move forward, the band had roped in producer Vini Poncia – a man whose CV included Peter Criss’ lounge-jazz and R&B influenced solo album, as well as albums by Wonder Woman star Lynda Carter and curly-haired pop twat Leo Sayer.

“I don’t know if it was Vini’s intention, or the band’s intention, but they wanted to explore the vocals and the harmonies,” says Dynasty engineer Jay Messina, who had first worked with the band on 1975’s earthshaking Destroyer alongside producer Bob Ezrin. “The more musical aspect of the band. And Vini was really good at that.”

“Vini was a very good friend of mine at the time,” says Stanley. “I enjoyed working with him, because it was working with a friend. I don’t necessarily mean that it was best for the band.”

Matters weren’t helped by the rapidly deteriorating relationship between an increasingly addled Peter Criss and his bandmates.

“Well, Peter wasn’t there for the most part,” says Messina. “Anton Fig played drums on Dynasty and also Unmasked. Peter did come by occasionally.”

Dynasty was an admirable, if not entirely successful attempt to move things forward. I Was Made For Loving You was a hundred thousand years away from their trademark stadium rock bombast; inspired by the band’s trips to notorious Manhattan nightclub Studio 54 (“It was the place to go,” says Jay Messina. “Paul loved to dance.”); its shameless hopping onto the disco bandwagon was as shocking as it was brilliant. The funk intro of Sure Knows Something was no less jarring, though at least that swiftly flipped into something more recognisably Kiss. Naturally, the band were savvy enough to throw their less open-minded fans a bone in the shape of Simmons’ thumping Charisma and X-Ray Eyes. Today, Stanley views it with mixed feelings.

“Vini brought a different element to the band, because he came from a different era and a different style of music,” says Stanley. “I loved that, but it doesn’t necessarily mean it had a place in the band. The danger of a producer is that they might have an interpretation of what they believe you are, and it can certainly dilute what you are if it’s not on target.”

Despite the success of I Was Made For Loving You, Kiss were wobbling like drag queens on nine-inch heels when they started recording the follow-up to Dynasty. Released in 1980, Unmasked would do nothing to assuage their hardcore fans. It eased back on the disco juice, only to replace it with the sort of uncharacteristically glossy pop-rock that screamed ‘surefire hit’ at the dawn of the new decade. This was MTV rock before MTV had even been invented.

“Unmasked is the product of a dysfunctional band,” says Stanley. “People were surrounding themselves with a lot of sycophants who were telling them what was best for them to hear, but was ultimately most destructive for the band. Was I guilty of that? (Laughs) Oh, of course I was guiltless.”

Sonically, Unmasked veered towards the featherweight. “There was more attention paid to the musicality than the raw rock’n’rollness of the band,” as Jay Messina puts it. But listening to it today, it’s a far better record than its reputation suggests. With a chorus the size of the Chrysler Building, Tomorrow is the first great Kiss anthem of the 80s, while Ace Frehley’s Two Sides Of The Coin and Torpedo dump a bucketload of Bronx grit all over the polished floors. The flipside was Stanley’s winsome Shandi, a bona fide AOR masterpiece that took its influence, oddly, from Bruce Springsteen’s Sherry. With its mix of fluff and steel, the album was a bridge between Kiss’s hard rocking 70s past and their AOR-flecked 80s future. Not that the dwindling Kiss Army felt that way at the time: the album limped apologetically to Number 35 in the Billboard charts.

“To point a finger at Vini would be crazy,” says Stanley. “We were the ones writing the songs. The buck stops here, for better or for worse. All those albums were products of the guys at the centre of the storm, and that was us.”

But if Dynasty and Unmasked were a sharp left and right turn respectively, their next album would be the sound of Kiss hitting the kerb and crashing straight into a concrete garbage can.

Released in 1981, Music From “The Elder” was intended to be Kiss’ grandest musical statement yet. Talismanic producer Bob Ezrin was back on board, alongside new drummer Eric Carr. The latter had replaced Criss in May 1980, just before they played their sole US show in support of Unmasked at New York’s 5000-capacity Palladium (a far cry from their previous New York gig, at Madison Square Garden). The first attempt to fix up Carr with a costume was less than successful. At management’s insistence, the new drummer was going to be The Hawk. Except the effect wasn’t quite what they wanted. “I looked like Chicken Man,” Carr later recalled. “I looked like a big chicken.” In the end, he would come up with his own persona: The Fox.

But neither this latest addition the Kiss menagerie nor Bob Ezrin could save Music From “The Elder” from utter disaster. A largely incomprehensible concept album about a boy defending the earth from a race of super-aliens set to a soundtrack of portentous neo-classical rock that sounded like a Poundstretcher Pink Floyd, it remains Kiss’ greatest folly. The whole experience was so bad that Ace Frehley appeared on just one track. He left soon afterwards, though the band wouldn’t officially announce his departure for another 12 months.

“”The Elder” was the result of temporary insanity,” says Gene Simmons. “We didn’t know which way to go.”

“We lost our focus,” says Stanley. “I found myself looking for the respect of people who were never gonna respect what I was doing. Critical acclaim? Who needs it? We built our career on doing things our own way.”

That may have been the case in the past, but as 1981 bled into 1982, the world was changing. MTV had launched the previous August, but Kiss had been slow to latch on to its potential. While the rest of the planet gleefully embraced this brave new televisual world, Kiss were battling for their very survival.

Losing one original member was careless. Losing two was foolish. Recording a grand folly that turned out to be the worst-received album of their career was positively suicidal. And Kiss knew it.

“Two members left because of drugs and alcohol and we’d just recorded “The Elder” – that was not an ideal situation,” says Gene Simmons with heavy understatement.

Still licking their self-inflicted wounds, Kiss had decided to top up the coffers and give themselves some wriggle room by releasing a compilation album, Killers. The plan was to put out a compilation of old Kiss classics, topped by four new tracks, produced by Michael James Jackson.

Enter Adam Mitchell. An easy-going Canadian who had scored a string of hits in his native country with 60s folk-rockers The Paupers, his CV featured such diverse artists as Cher, Art Garfunkel and Merle Haggard. In 1982, he had just come off the back of co-writing Tears, a hit single for John Waite, with a hotshot guitarist named Vincent Cusano when he got the call from Jackson.

“He said, ‘Listen, Kiss would like to do some co-writing, would you like to do it?’,” recalls Mitchell, who admits he wasn’t a Kiss fan before he started working with them. “The Elder had been a disaster,” says Mitchell. “They were actually afraid that it was over. The brief was, ‘Let’s get back to what Kiss does. Enough of this concept album nonsense. Let’s write some really good Kiss rock’n’roll songs.”

Mitchell quickly struck up a good working relationship with Simmons and especially Stanley. With the latter, he would pen two new songs, Partners In Crime and I’m A Legend Tonight for Killers, The other two were Stanley’s Nowhere To Run and Down On Your Knees, a co-write between the singer and a young Canadian songwriter named Bryan Adams. Tellingly, there were no new Gene Simmons tracks on the album.

If Killers sounded like a contractual stop-gap designed to nudge the band back towards safer ground after the debacle of The Elder, that’s because it’s precisely what it was. And while none of the songs were truly memorable, they at least sounded focused. (And for Mitchell, it was the start of a close bond with Stanley. “Paul and I, when we were both single, we went out two or three times a week,” says Mitchell. “At one point we even dated roommates.”)

What it didn’t solve was the problem of the Ace Frehley-shaped hole in the Kiss’ line-up. Bob Kulick, guitarist with cult AOR heroes Balance and a man who actually auditioned for Kiss back in 1973, stood in for Frehley on the new tracks from Killers (a role he had filled a few years earlier, when he overdubbed the Kiss man’s guitar parts on Alive II). But Kulick was unhappy with his playing being steered towards fitting the Kiss format.

The band subsequently auditioned around 80 guitarists to fill the vacant slot. Among was them future Bon Jovi man Richie Sambora. “They like the way I played,” Sambora later recalled, “but they were going, ‘You know this one? That one?’ And I’m going, ‘No!’.” Another contender was Eddie Van Halen, who was increasingly unhappy in the band that bore his name; he would be talked out of it by Simmons and Eddie’s brother, Alex Van Halen.

None of which helped Kiss, and the situation wouldn’t be resolved by the time they started work on their next album, Creatures Of The Night even before Killers was finished.

“When we started doing Creatures Of The Night, Paul and I wrote Creatures and a couple of others,” says Mitchell. “I ended up playing one of the guitars on the song Creatures Of The Night – that riff in the middle, that’s me playing it.”

The album would eventually feature a multitude of ghost guitarists, including Mister Mr’s Steve Farriss and jazz-rock man Robben Ford. Another was Adam Mitchell’s sometime songwriting cohort Vincent Cusano.

“I am the one who introduced Vinnie to Kiss,” says Mitchell with a sigh. “They tried him out and his musical talent meant he was perfect for them.”

At Mitchell’s behest, Cusano was brought into the fold as both a songwriter and one of the numerous guitarists roped in to play on the album. Even though he doesn’t feature on every track, his impact on the record was immediate: Creatures Of The Night turned up the dials to ‘heavy metal’ and banished the lingering aftertaste of Music From “The Elder”. Kiss sounded hungry again, and that was partly down to Vincent, who co-wrote two of the album’s highlights, I Love It Loud (with Simmons) and show-stopping power ballad I Still Love You (with Stanley).

“Vinnie is a phenomenal talent,” says Adam Mitchell. “He plays like Ace, only way, way better. But – and it’s a big but – there were personal issues right from the get-go. And they got in the way in the end.”

“Vinnie was an excellent co-writer, and somebody with real ability on the guitar, which nine out of 10 times he sabotaged or just obliterated,” says Stanley. “But in the studio, that could be harnessed and moulded into what it should be as opposed to where he invariably wanted it to go.”

For now, though, Cusano was the favourite candidate as full-time replacement for Ace Frehley. By the end of 1982, he had officially joined Kiss – though as a salaried, “non-voting” member. He was given his own make-up and persona: The Wizard. He was also asked to adopt a stage name. The guitarist’s own choice, Mick Fury, was blocked; instead, he was dubbed Vinnie Vincent.

“What was hard for me was taking the place of someone that fans really loved. I did not want to take anyone’s place,” said Vincent in Ken Sharp’s official Kiss biography, Behind The Mask. “I was just there because I was asked to be there.

Despite his reservations, an Ankh-faced Vinnie Vincent made his stage debut with Kiss in Bismark, North Dakota, in December 1982. The album had been released two months earlier, and hailed as a return to form. The only snag is that people weren’t buying it – it creaked into the US charts at 45. Neither were they buying concert tickets. The subsequent US tour found the band playing to half empty venues; an ignominious fall from grace for a band who were one of the biggest draws of the 70s.

“In June 1983, Kiss played the largest show we ever played, at the Maracana Stadium in Rio,” says Simmons. “There was anywhere from 190,000 to 210,000 people there. It looked like a nation – Kiss nation. We came back to America and it was dead. We’d done our heaviest album ever, cos we felt that we had something to prove. But the masses weren’t ready for it. Creatures Of The Night halted – it just didn’t work. It had to do with upheaval within the band and the upheaval of the times. We took a look at each other and went, ‘What are we gonna do?’.”

The answer was simple: take off the make-up.

Paul Stanley and Gene Simmons both stand by Creatures Of The Night, and rightly so. “Creatures was really a reaffirmation of us trying to get back on track from having been completely clueless for a while,” says Stanley. “Lick It Up was the next step.”

If Vinnie Vincent was unhappy with his situation in Kiss, he wasn’t letting on as Kiss entered New York’s Record Plant and Right Track studios with producer Michael James Jackson to record their fourth album of the decade. Lick It Up took the metalized blueprint of its predecessor and added some 80s flash: Exciter (featuring a guitar solo courtesy of Rick Derringer) showed the trials of the last few years hadn’t blunted their edge, while the title track was a bona fide AOR anthem.

“Lick It Up was a really good album, though on a lot of levels I thought Creatures was better,” says Stanley. “But I thought that a good reason for taking off the make-up was because people were listening to the albums with their eyes, and they didn’t want to see the make up. The make-up detracted from the music.”

And so, midway through 1983, Kiss made the momentous decision to wipe off the greasepaint. Stanley had wanted to lose the make-up for Creatures Of The Night, but Gene Simmons was having none of it. “We worked in a way where if someone doesn’t want to do something, we go with that person,” says Stanley. “In this case, it was a monumental move for him, so we didn’t do it.

“I went, ‘What!? That’s sacrilegious!’ You’re out of your mind. It won’t work’,” says the bassist now. “It was actually Paul who felt more comfortable. Intrinsically, Paul onstage is closer to who he is offstage than I am. For me, it’s psychic trip – onstage, it’s cathartic, I let out the inner demos.”

The subject was raised again as the band recorded Lick It Up. Simmons was still unconvinced, and remained so until the very last minute. “So we had recorded Lick It Up with a new line-up, and the material was what the material was,” says the bassist. “We stood around with a photographer and just took photos. I said, ‘Well, we look like every other band’. One of the shots had me sticking my tongue out – we had to have some kind of connection with Kiss as we were before, or otherwise we’re just Britny Fox or Cinderella. So I closed my eyes and went, ‘OK, let’s try it’.”

The band had come to appreciate the value of MTV, and it was via the increasingly powerful music channel that they opted to make their big reveal. And so, at 11pm on Sunday, September 1983, the four members of Kiss finally made their first official public appearance without make-up, even if the day and time-slot of the broadcast only illustrate the reduced circumstances they found themselves in after a couple of flop albums.

“For me, the day was anti-climactic,” says Stanley. “It wasn’t the original band. The mystique revolved around the original four guys. Once that was gone, it was just a nice press angle. For me, it didn’t have the same impact.”

But the partnership between Kiss and MTV was certainly had its upside. The newly unmasked band had made a video for Lick It Up – the first Kiss video to be picked up by the channel. Over the subsequent years, the power of the channel to make or break bands may well have made an impact – conscious or subconscious – on the more melodic direction the band took.

If Kiss’ big day failed to move Stanley, it was a different matter when the band found themselves onstage sans the Max Factor for the first time. “The first show without make-up was quite jolting,” says Stanley. “I remember looking across the stage and thinking, ‘What the hell are we doing in front of an audience in these clothes?’.”

There were more serious problems for Kiss than stepping out onstage without their battle dress and make-up. Always a difficult character, Vinnie Vincent was becoming visibly unhappy in the band. And he was starting to act up. At a show at the LA Forum, he deliberately extended his guitar solo, keeping an increasingly apoplectic Stanley waiting for his cue at the side of the stage. In the dressing room afterwards, the pair reportedly came close to a fist-fight. The end was in sight for The Wizard.

“I just wasn’t living up to my full potential,” said Vincent in 1985, shortly after his inevitable departure from the band. “I wasn’t able to be who I am. I wanted to do things that would have made the group more exciting and more meaningful. Lick It Up probably shows about 25 per cent of what I’m capable of achieving.”

Today, Vincent has seemingly stepped away from music. Since leaving Kiss (“He was most definitely fired,” Stanley has confirmed), he released two albums with his band, the Vinnie Vincent Invasion; bizarrely, given the acrimony that surrounded his departure, he also contributed to Kiss’s 1992 album Revenge. According to Simmons he has sued the band 14 times, each one unsuccessful. Attempts to contact him for this piece proved fruitless.

“It’s well documented,” says Stanley, firmly. “It’s nothing I need to go into. But he’s his own worst enemy, in addition to having a multitude of other enemies out there now. He’s somebody who is not the kind of person I want to be around.”

Ironically, all the pain was worth it. The melodic rock edge of Lick It Up helped it become the first Kiss album to sell 500,000 copies in the US since Unmasked.

“Where Creatures Of The Night died, Lick It Up came out and actually worked,” says Simmons. “It became a big record, and the concert halls filled up. Without the make-up.”

Kiss were back on track. Or at least some of them were.

If the first half of the 80s had been Kiss against the world then the second half would be Kiss versus themselves. When they began work on 1984’s Animalize, the times were changing. Though Kiss’s vision had started to dovetail with that of the MTV programmers, Def Leppard’s Mutt Lange-produced Pyromania had raised the bar on what a rock record could and should sound like; elsewhere a new breed of bands were nipping at Kiss’s Cuban heels, among them a poodle-permed New Jersey outfit named Bon Jovi.

“We started working on Animalize, but there was upheaval,” says Simmons. “Vinnie Vincent was a problem. He had to go. And music itself was changing. English pop came in with synthetic drums. It was the decade of Duran Duran and the Thompson Twins and all that stuff. And rock itself was changing – the hair bands became popular. The idea was that you had to look better than your girlfriend.”

At least Kiss had a new guitarist to keep themselves moving forward. Mark St John – born Mark Norton – was a California-born six-string hero-in-waiting who the band picked after a string of auditions. In keeping with the times, he had a flashy contemporary style that was more Yngwie Malmsteen than Ace Frehley.

“I come from an older school of guitar players,” says Stanley, “and the 80s were immersed in guys doing slide whistles and calliopes on their guitars, playing it with the whammy bars, turning it into something that isn’t even a guitar as far as I’m concerned. But it was a component of bands at that point, and it needed to be incorporated. But that was another point where the band was going through more changes. We had a new guitarist. And there was a bass player who was AWOL.”

More than 25 years on, Gene Simmons freely admits that by the mid-80s he had taken his eye off the Kiss-branded ball. “I started getting movie offers,” he says with a shrug. “And I’m not the sort of person who is happy doing just one thing.”

Simmons’ screen career was stuttering but eventful. In 1984, he starred as an evil scientist alongside Tom Selleck in the sci-fi film Runaway; the same year he appeared in an episode of Miami Vice as a nattily-dressed pimp. Over the next few years, he popped up as a radio DJ in shlocky horror flick Trick Or Treat and in a truly has-to-be-seen-to-be-believed role as transvestite super-villain Velvet Von Ragnar in straight-to-video ‘thriller’ Never Too Young To Die.

“Yeah, I lost it in terms of spending time being committed to the band full time,” he says now. “I succumbed to Hollywood, to pop culture, to the hair bands, to the times. Guilty as charged.”

It was left to Stanley to steer the Kiss ship, and he stepped manfully up to the wheel. With his bandmate absent, the singer took on the task of producing the album. Any disgruntlement he felt with Simmons was overshadowed by the problems he was having with Mark St John.

“Mark was kind of strange, because I’d send him home to construct a solo, then he’d come in the next day and play it,” says Stanley. “And I’d say, ‘Play it again’, and he’d play a completely different solo. I ended up either singing the solos to him or sometimes even punching in and playing some of them. I would say to Mark, ‘Go home and listen to Paul Kossoff’. He would say, ‘I can play faster than he can’. I said, ‘That’s the problem.’ He would look at me like I was speaking Mandarin.”

St John had a different take on the situation. “I don’t know why they even booked studio time when none of them were there,” said the guitarist in the late 80s. “Gene was doing a movie in Canada, Paul was in Bermuda with (disco singer) Lisa Hartman that week, and Eric was in Florida, fucking some girls. So I’m in the studio recording – just me and a couple of engineers.”

It’s a mark of Stanley’s stubborn determination and general dedication to the Kiss cause that not only was Animalize finished without the singer murdering at least two of his colleagues, but that it sounded so good. That fact that it’s one of the most overlooked albums in the Kiss cannon can’t detract from the fact that it stands as 35 minutes and 42 seconds of matchless 1980s AOR-tinged arena rock. At its best – Heaven’s On Fire and the Jean Beauvoir co-write Thrills In The Night – it more than matched the cream of their 70s output, and placed Kiss at the head of the melodic rock pack.

For his part, Gene Simmons was happy to cede control of the studio to his bandmate. “Well, who else could do it?” says the bassist now. “I hate the studio. To me it’s like pulling teeth. Some bands love it. But there’s something that happens onstage that you can’t get anywhere else. I need to be worshipped as the god that I am.”

Paul Stanley is less jocular. “Making that album was basically me getting people to implement what I needed,” he says. “To play the parts I couldn’t.”

One victim of Stanley’s bloodless coup was the unfortunate Mark St John. “There are two songs on Animalize I didn’t play on: Lonely Is The Hunter and Murder In High Heels,” St John told Kiss biographer Ken Sharp. “I had reactive arthritis. My knuckles on my left hand were swollen up, and so were my left kneecap and my Achilles Tendon. So I virtually had to walk with a cane.”

St John would later put his ailment down to the stress of the situation, but it presented a more immediate problem. The band were due to kick off the Animalize tour in the UK, and St John was in no fit state to play live.

Step forward, Bruce Kulick.

Of all the people who have passed through Kiss, the recruitment of Bruce Kulick was the most unusual. The younger brother of one-time Kiss session guitarist Bob Kulick, Bruce first met Paul Stanley via his brother in the late 70s. “My brother would say, ‘I have a car, let’s go hang out with Paul’,” says the guitarist. “We’d go to a pub named Privates in New York that was pretty hip, catch a movie, stuff like that.”

Kulick had also taken part in the mass audition before they recruited Vinnie Vincent. “Then Vinnie pulls whatever it was that put him out of the picture, and they’re looking for a hotshot guitar player,” he says. “All of a sudden, Mark St John is top of the list. I remember seeing the photo in Kerrang! magazine, page 24. I was like, This guy is wrong. This guy should not be in Kiss! I had nothing against Mark, and it wasn’t like I should have been in Kiss. It was just wrong.”

When St John began having health problems during the recording of Animalize, Kulick’s name came up as an extra pair of hands. “My brother used to do that, so when I got a phone call I was shocked: ‘Wow, they went to the younger brother, this is cool’,” says Kulick.

The guitarist would play on the two Animalize tracks that St John was unable to complete. “I was thrilled. It was easy to work with Paul, I liked the vibe, and then he said a couple of prophetic words to me: ‘Don’t cut your hair.’ I was, like, ‘Why is he saying that? He’s gotta be thinking that something is going on’.”

In late August, his suspicions were confirmed. Kulick received a call asking if he could fly to England to stand in for Mark St John. “I could tell that it didn’t look like they were gonna drag Mark over there,” says Kulick. “But it didn’t look like they were letting him go immediately. I don’t know if it was a contractual thing, they kind of wanted to play it out because they made a big stink about him being the new guitarist.”

Kulick’s first gig as a temporary member of Kiss was in Brighton on September 30, 1984. He recalls that he was so nervous that his knees were literally knocking.

“I got the nickname Spruce Goose right there,” says Kulick, “because I was afraid to move. All of a sudden it’s like those guys had ants in their pants. We didn’t do a rehearsal like that. I kinda froze up. I got some intricate guitar parts here – some of Animalize isn’t exactly two chord rock.”

When they returned to America two weeks later, Kulick was kept on for the subsequent US tour. This time, St John accompanied the band on the road. The plan was to ease him into the show with short ‘guest’ spots, building up to an entire show at the tour’s conclusion.

“It was a strange situation, but I wasn’t gonna do a Nancy Kerrigan – I wasn’t gonna club him in the middle of the night in the hallway,” says Kulick. “We even used to jam a little bit backstage. I kept it very positive – I knew I had the home team advantage by touring with them. But the truth was that they knew that I had it down and I knew how to do this.”

Kulick’s self-assurance paid off. Arthritic or not, by the end of the tour Mark St John had sunk himself. “He didn’t do badly when he had those chances to do parts of the show, and then a full show,” says Kulick. “But he was kind of trying to upstage them, which is a really bad thing. And then that was it.”

Mark St John’s final gig as a member of Kiss was on November 29, 1984, at the Veteran’s Memorial Arena in Binghamton, New York; his tenure had lasted all of eight months (sadly, he died of a cerebral haemorrhage in 2007).

“It was sometime in December in 1984 that I got that phone call: ‘Hey, we want you to be the guy,” says Kulick. “I remember Paul calling me and I was thrilled. ‘Wow, I got the gig!’ I never got the big splash of ‘New guitarist of Kiss!’, but then there’s a lot of pressure that comes with that.”

Within a few months, Kulick was holed up with the rest of Kiss in New York’s pre-eminent studio, Electric Ladyland, for his first official Kiss record, Asylum. It was a baptism of fire, not least seeing the push-pull dynamic of the Stanley-Simmons working relationship at close quarters.

“At the time, they were competing all the time,” says Kulick. “That doesn’t sound healthy, but it was. They worked independently, then together. Gene is just a workaholic. Was he able to be in Kiss and pursue an acting career? Yes. Paul didn’t quite see if that way, but then again it gave Paul purpose to say, ‘I’m gonna produce the record, I’m gonna take over here’.”

With Bruce Kulick on board, Eric Carr was no longer ‘the new guy’. Five years in, and the lustre of being the drummer in Kiss was starting to fade.

“When I first joined the band, the excitement and the fun of it wasn’t… in the forefront of Eric’s mind,” says Kulick. “It was more like he was getting disillusioned. I used to get a lot of gripes from him, and I was, like, ‘Would you shut up! Do you realise how lucky you are?’.”

Like Vinnie Vincent, Carr was getting restless. But the drummer’s frustrations manifested themselves in less confrontational ways.

“Eric was a sweet, funny guy, but he acted out sometimes,” says Kulick. “There was a funny thing that happened in England on the Animalize tour. Some journalist from the NME or one of those magazines befriended him. The next thing you know, there’s photos of him in the bathtub, drinking champagne, splashed in the paper. That didn’t go down very well. At the airport the next day, Gene and Paul were like, ‘What were you thinking?’ He was a little unhappy, so that was him going, ‘I’m gonna get in trouble with the parents.’ I’d never put myself in that position. If I wanted to have fun with a girl, there was never gonna be a camera there.”

With the release of Asylum highlight Tears Are Falling as a single, Kiss confirmed their status as the darlings of 80s MTV rock. That single was a prime-time slice of 80s soft rock, leagues away from the outright 70s aggression of the likes of 100,000 Years.

For all the resurgent success that Animalize and Asylum brought, by 1987 Kiss found themselves playing catch up with the bands they’d inspired. Bon Jovi, who had supported Kiss in the UK on the Animalize tour, had shifted several million copies of their third album, Slippery When Wet. Poison and Cinderella weren’t far behind. The fact that these bands ramped up the glamour wasn’t lost on the men who helped invent the look.

“Because of the success of those bands, and a lot of others who were very comfortable doing what they were doing, we succumbed to it,” says Gene Simmons. “I remember being at an airport shopping mall in Minneapolis. I walked past this woman’s dress store and I saw this thing and I stopped. I don’t what it was – it was red and it was shiny and had all these little pieces that moved. I went: ‘I gotta buy that’. And I put this thing on and of course it ripped on the sides. So I had the seamstress add some fabric. I just thought I looked like peaches and cream. It was the most embarrassing cross-dressing thing you could ever imagine. I looked like a football player in a tutu.”

While they couldn’t match their younger rivals sartorially, the musical playing field was at least more level. Two consecutive platinum albums had given the band a renewed confidence as they entered the studio to record their 14th studio album. Or at least for Paul Stanley it had. Gene Simmons, on the other hand, was altogether less engaged with the matter at hand.

“Gene can say whatever he wants about being disenchanted with the 80s,” says Stanley. “But he was the problem. Or part of the problem. When he was out doing other projects, or trying to become a TV star, or working with other bands – and he would have been better off sleeping than working with some of the calibre of bands he worked with – it compromised everything he did.”

After two albums that had ostensibly been helmed by Stanley (though the production credits read Stanley-Simmons), the singer decided it was time to bring in an outside producer. In this case, it was Ron Nevison, the man who had overseen Ozzy Osbourne’s slick The Ultimate Sin and Heart’s career-saving multi-platinum self-titled 1986 album and its equally successful follow-up, Bad Animals. Nevison was the go-to guy for 80s rock with a hi-vis pop sheen.

“Paul was really excited by Nevison,” says Bruce Kulick. “He befriended him, they were hanging out. Paul had nine songs ready to go for the album. Gene was not in bed with Nevison at all, vibes wise, because I think he thought he might be too pop.”

Any objections the bassist might have had were undermined by the fact that he’d effectively let Stanley sit in the driving seat. “He was either in the studio tired or bringing in material that was sub-par at that point,” says Stanley. “It was very gradual, but certainly during Crazy Nights, it was becoming clear that I was not happy pulling all the weight. I said, ‘This doesn’t work for me – I either have a partner or I don’t. I’m not looking for accolades. I’m looking for input’.”

Crazy Nights was treated sniffily on its release, but today its shamelessly commercial approach has aged incredibly well. The gang vocals of MTV staple Crazy Crazy Nights and skyscraping AOR synths of Turn On The Night approach pop-rock perfection, while Reason To Live is the greatest ballad Foreigner never wrote (though given the fact it sounded suspiciously like I Want To Know What Love Is, Mick Jones could have justifiably claimed to have written it anyway).

Today, Stanley looks back on the album with mixed feelings: proud of some of the music, but undeniably narked at the circumstances in which it was made.

“It may be admirable to stay in a leaky ship and keep bailing water, but it doesn’t get the same result,” says Stanley. “I didn’t do that by choice. And what was lacking was my team mate’s commitment. The work he was bringing in was sub-par, but the bottom line is that he was absent. Did it feel like I was flying the Kiss flag alone at that point? Oh totally. That’s no secret. It was in my hands.”

Things weren’t much better with the follow-up, 1989’s Hot In The Shade. While Gene had taken Paul’s criticisms on board, the recording of the album was still less than smooth – not helped by the fact that they’d decided to co-produce it.

“I think they wanted to return to straight-ahead rock’n’roll,” says Bruce Kulick. “So the record started off as demos, which we then started overdubbing. I understood why, but I didn’t like that whole approach. We were back with Gene and Paul producing, which means the two of them are gonna compromise – ‘I like that song of yours, but I don’t like that one’; ‘Well, if you let me use mine…’ That was one of the weaknesses of the two of them producing.”

“Hot In The Shade was very fragmented, very piecemeal,” says Stanley. “We were like a ship without a captain.” So much so that the singer decided to embark on a solo tour at the end of 1989.

After the pop-rock glories of Crazy Nights, Hot In The Shade – note the tongue in cheek acronym its initials form – sounded like a step backwards. The likes of Prisoner Of Love and Desmond Child/Holly Knight co-write Hide Your Heart were proficient, by-numbers arena rock. Handily the glorious power-ballad Forever provided them with their biggest US hit in years, though it would be Bruce Kulick playing bass rather than Gene Simmons on the song. But for all the ongoing strains, there was a light at the end of the tunnel.

“When we went on tour, we rallied,” says Stanley. “We began to embrace our history. We would literally hit every period of the band, and we did it proudly.”

- The Car Crash That Killed Hanoi Rocks' Razzle: 'Vince Neil never apologised…'

- Guns N’ Roses add extra London date

- Tony Iommi to receive more cancer treatment

- Emerson, Lake & Palmer’s Greg Lake dies aged 69

Kiss left the 80s in much better shape than they entered it. They had a stable line-up and a sales graph that was headed upwards rather than downwards. There was just one dark cloud on the horizon: in 1990, Eric Carr would be diagnosed with a cancerous tumour in his heart. Sadly, the drummer died of complications from the disease on November 24, 1991. Kiss’ next album, 1992’s Bob Ezrin-produced Revenge would be dedicated to the drummer.

“In hindsight, we knew we needed a catalyst, somebody to focus us,” says Stanley of that record. “And Bob Ezrin seemed like the right choice. Working with Bob was a pleasure, and he had the discipline that we enjoyed. And we were pleased with it. I didn’t love everything on it, but that’s what you give up when you have a producer.”

Ezrin certainly helped pull Kiss together for an unexpectedly cohesive album. He also helped channel the natural competitiveness between Simmons and Stanley.

“Are they in competition?” says Kulick. “In many, many ways, throughout their entire career. But as much as it causes some problems, it’s actually created one of the biggest bands in the world. It’s healthy competition.”

It was arguably this competition that kept the band together while other, less stubborn bands would long have packed away the leather trousers and silk shirts. Looking back on Kiss’ most tumultuous decade, Gene Simmons admits culpability for at least some of their difficulties.

“The songs I wrote in the 80s were nowhere near what they should have been,” says Simmons. “I got caught up with it. I was seduced by the times.”

Stanley draws an analogy with an Olympic athlete. “You go in there to best yourself. And sometimes you don’t have the capacity. Every time we went in the studio, we went in with the idea of making a great album. But every time we went in the studio, we were trying to make a great album under whatever the circumstances were. And whoever was in the band and whatever the politics were. Let’s be honest, at different times, everybody has been MIA in this band. But without patting myself on the back, I certainly showed up every day and gave it my best.”

The singer says that he hasn’t listened to Kiss’ 80s albums in their entirety for a long time. But he sees the value of the records – and everything they went through to make them.

“They were all part of getting us back to where we are now,” says Paul Stanley. “We faltered, and we certainly got lost. But out of those lost periods came some really good stuff. There are some real gems in there.”

This original appeared in Classic Rock Presents AOR 10