Mention the Eagles in any conversation, and within minutes someone will invariably quote Jeff Bridges’s character The Dude in the Coen Brothers’ 1998 flick The Big Lebowski: “I fucking hate the Eagles, man!” Few superstar bands are as polarising as the Eagles. That they’re one of the most successful bands in history is beyond doubt. Ditto the fact that they helped define an era – specifically the second half of the 1970s – in which bands were elevated to the status of Roman emperors, with all the money, indulgence and hedonism that implied.

They have their fans, and millions of them at that, who proclaim a love – or at least admiration and respect – for the band who came to embody Southern California’s mellow-70s scene. Fans who celebrate the band’s songcraft, their workmanship and their vocal harmonies. But there are just as many people who hate the Eagles for what they were and what they became. Some native Californians are still angry about the limp image the band – comprised exclusively of non-California natives – bestowed on their state. Some dislike the whiff of misogyny around their lyrics. Many more hate their pretentiousness and humourlessness, the pomp and excess they became associated with, and the arrogance that surrounded them – more specifically, drummer/vocalist Don Henley and guitarist/vocalist Glenn Frey.

Unlike their contemporaries Fleetwood Mac – the other quasi-Californian band who helped usher in the age of Superstar Rock – the Eagles have never managed to truly disentangle themselves from the less glorious elements of what they once were. These days you’re likely to hear the Mac praised by modern hipsters who still hate the fucking Eagles, man.

But there was a time when the Eagles were considered to be a pretty cool band. If, like me, you were a then-recent high-school graduate who saw them perform a sold-out show at Detroit’s 12,500-seat Pine Knob amphitheatre in August 1974 on the back of their third – and best – album, On The Border, none of that mattered one iota. The Eagles were a cool band to most of us at the time – we wouldn’t have bought tickets if we’d thought otherwise. The only thing on our minds might have been how rapidly the band’s star had risen since they opened for Yes in a small auditorium in the Motor City two years earlier.

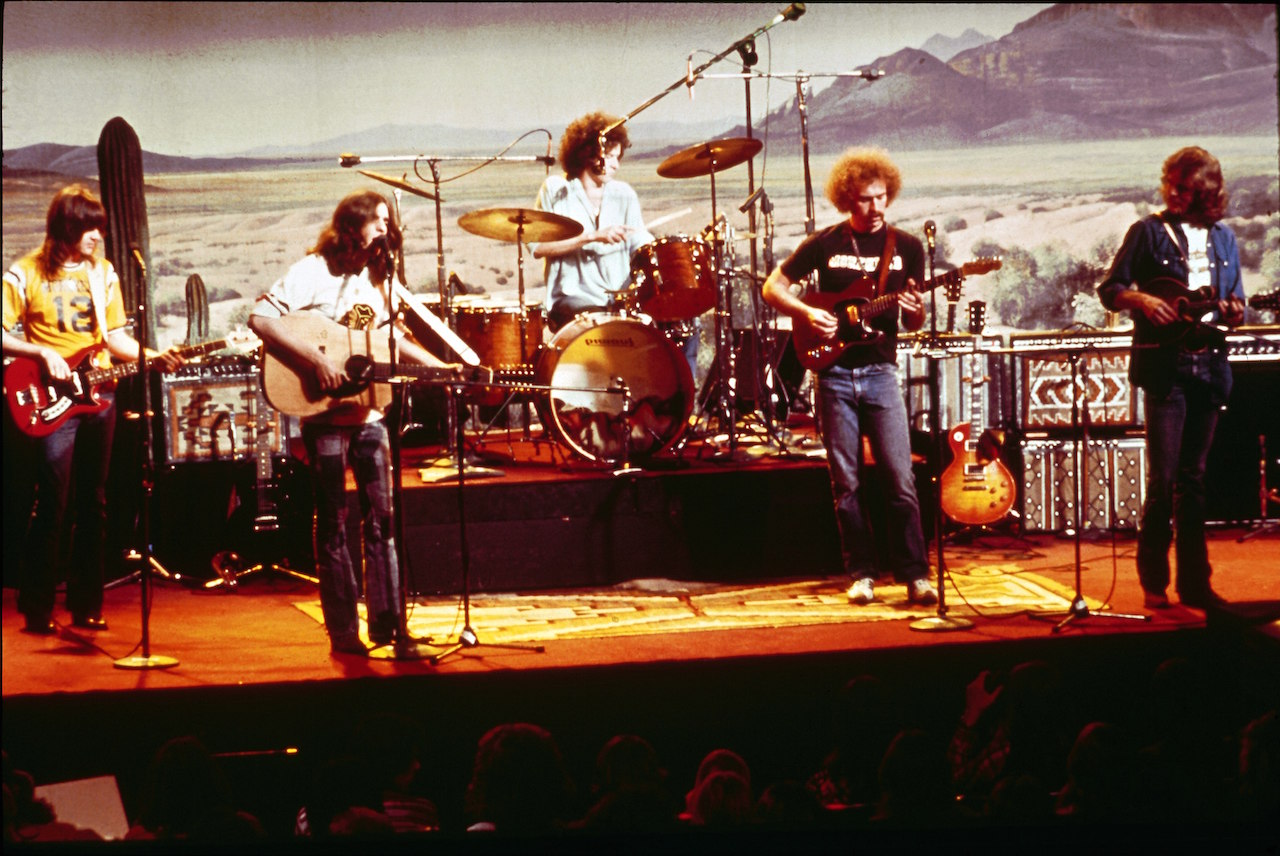

They may have symbolised the era of post-Watergate cynicism and the transformation of counter-cultural idealism into a kind of corporate glamourisation of hippie power, but the Eagles were damn good that night. In their simple uniform of T-shirts, tennis shoes and faded denim, they perfectly reflected their audience. Their trademark harmonies were flawless and soaring. Most importantly, they rocked, their sound fleshed out by the addition of new guitarist Don Felder. That night the Eagles were certainly cool.

They returned to play two sold-out shows at Pine Knob in June 1975, two weeks after the release of their fourth album, One Of These Nights. These gigs came the night after a four-night sold-out engagement at New York’s Madison Square Garden and less than a week after the band had co-headlined Wembley Stadium with the Beach Boys. At that gig they had prophetically covered Chuck Berry’s Carol with guest guitarist Joe Walsh, at the time riding high as a solo star.

Aside from the addition of the title track from the new album, little had changed since the shows the previous year. The sets were very similar, although the addition of Berry’s Carol as an encore reflected the more ‘rocking’ direction that Glenn Frey especially was pushing for. By the end of that ’75 tour, however, everything had changed. The band were still cool to most of the people who made up their audience, but they were about to lose something in pursuit of the mega-success they were always so clearly after.

As veteran Southern California musician Chris Darrow, who was replaced by original Eagles guitarist Bernie Leadon in the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band and subsequently recruited Leadon for his next band, The Corvettes, puts it today: “The Eagles had to happen – it was just a question of when and with whom.”

Even from the get-go the Eagles were scorned by purists who viewed their music as a cynical bastardisation of everything great that such illustrious forebears as Dylan, The Byrds, Buffalo Springfield, Poco and the Gram Parsons-led country-rock pioneers the Flying Burrito Brothers had previously brought to the form. Parsons himself famously referred to the Eagles’ music as “a plastic dry-fuck”. Others saw them as nothing more than a prefabricated band – a country-rock Monkees.

It’s easy to see why. When Henley and Frey first hit on the idea of a ‘supergroup’ that would bridge both of those musical worlds, they had no songs. The only thing all four original members (the line-up rounded out by Bernie Leadon and bassist/vocalist Randy Meisner) had in common was that they all had once played in Linda Ronstadt’s band, although, with the single exception of a Disneyland gig, not at the same time. In truth the concept of a country-rock supergroup wasn’t even theirs; it was the brainchild of Ronstadt’s manager, John Boylan, who considered forming such a band around the singer.

In their defence, they did have some genuine ties to the music they were tapping into. Meisner had been in both Poco and Rick Nelson’s influential Stone Canyon Band, while Leadon – who, thanks to his extraordinary musicianship and influence, was in many ways to the Eagles what Brian Jones had once been to the Rolling Stones – had played with Gram Parsons in the original Flying Burritos, as well as the classic Dillard & Clark band and Poco.

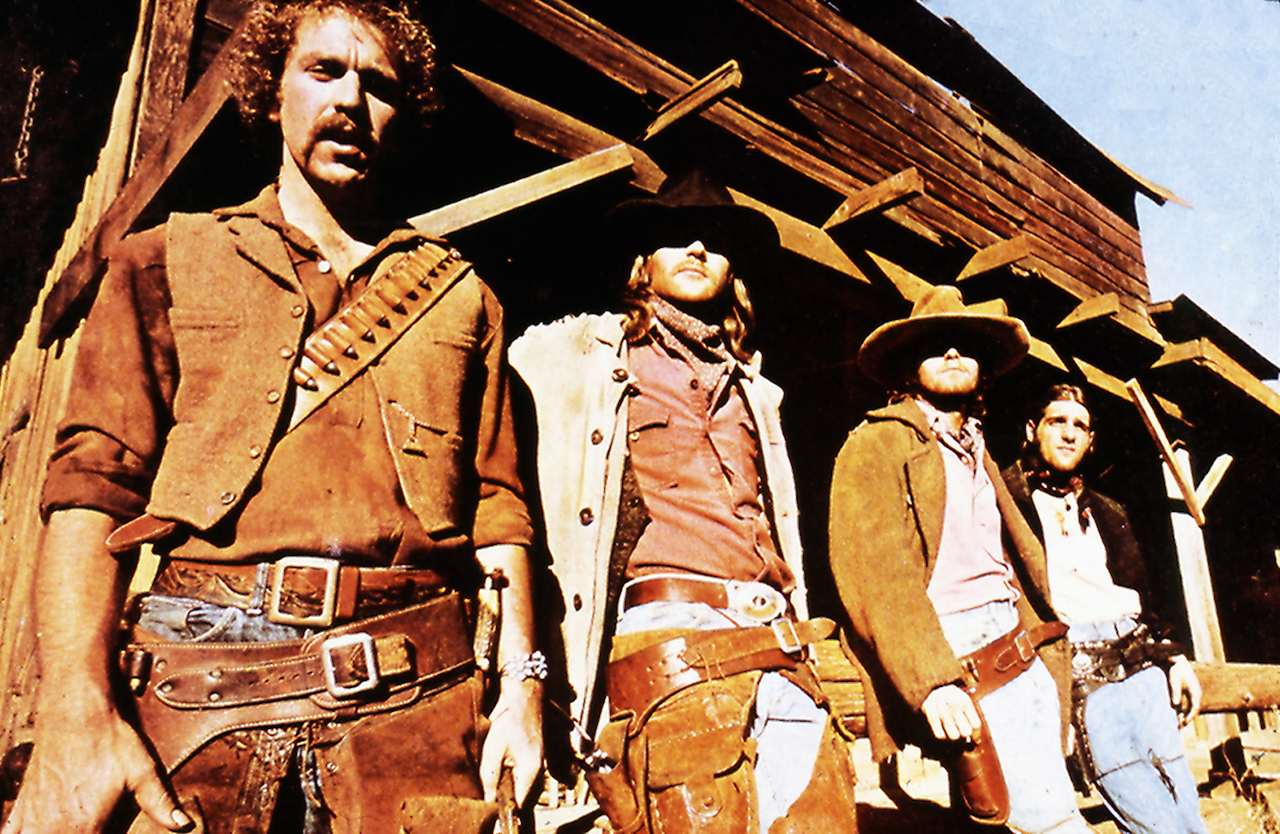

They still had no songs when they went to manager and Asylum Records founder David Geffen – Bernie Leadon famously greeting the young music mogul, whose management clients had included Joni Mitchell and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, with the words: “Do you want us, or not?” Geffen nevertheless signed them on the recommendation of Jackson Browne, and sent the quartet to Aspen, Colorado to learn to play together and to come up with some songs, and subsequently across the Atlantic to London to make their self-titled debut album with producer Glyn Johns.

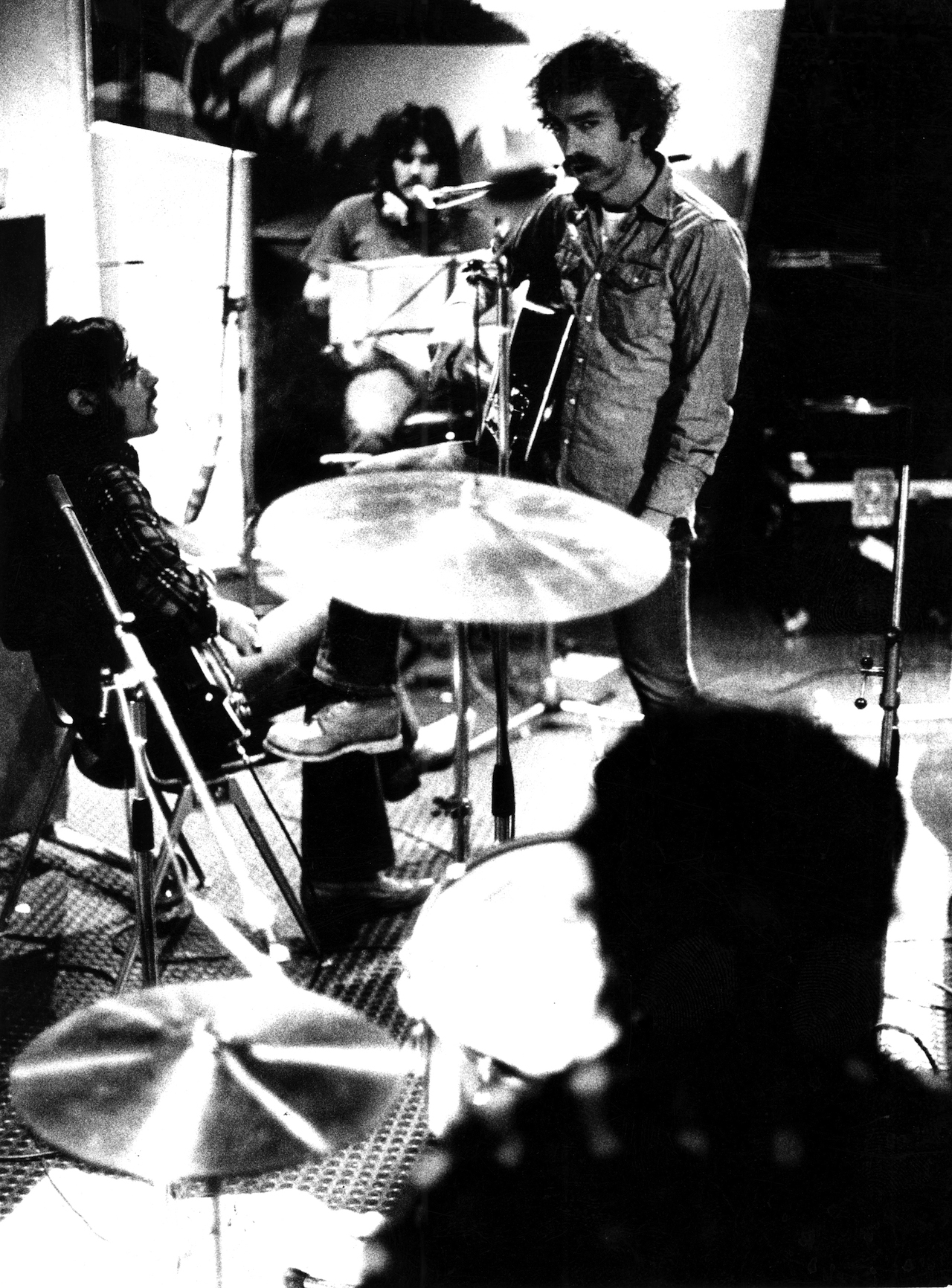

If anyone might be considered a patron saint in the early years of the Eagles, it would have to be Johns. It was the producer who realised those pristine vocal harmonies as the fledgling band’s strength, and who helped shape their defining sound after finding them “confused” when work began on their debut album.

Eagles was an instant success when it was released in the middle of 1972, breaking into the US Top 30 (a feat repeated by each of its three singles: the Glenn Frey/Jackson Browne co-write Take It Easy, Leadon’s Witchy Woman and Peaceful Easy Feeling, the latter written by Frey alone). The band had hit on a winning formula straight away. Much like Grand Funk Railroad had done with the MC5 or Alice Cooper Cooper did with The Stooges, the Eagles succeeded in taking one of rock’s sub-genre’s, in this case country-rock, and moulding it in their own image, diluting and filtering out its rough edges and ultimately taking it to the masses.

The successful formula would be repeated on the even more ambitious and conceptually thematic Desperado. But when the Eagles returned to England in late 1973 to begin work with Johns on their third album, things were suddenly amiss, especially between the producer and Frey.

“Glenn and Glyn were like oil and water,” recalls Henley in the documentary History Of The Eagles. “We couldn’t think over there,” Henley said at the time. “We couldn’t create. We were too busy trying to find a good restaurant.”

The truth was that Frey felt the Eagles were a rock band, and that they should be recording rockin’ songs. Johns, who had produced Who’s Next and co-produced Led Zeppelin’s debut album, thought otherwise, and tried to convince them that their strength was country-pop. Not that Henley disagreed with his bandmate. “I hate when people call us a country-rock band because they are so full of it,” he complained to Phonograph Records Magazine in 1975. “We can do rock’n’roll, we can do country music – anything.”

In Henley’s view, Johns was part of the problem. The producer discouraged them from playing rock songs in favour of pretty acoustic ballads.

“He was the key to our [early] success in a lot of ways,” Frey admitted to Rolling Stone magazine. “He didn’t want to hear us squashing out Chuck Berry licks. I didn’t mind him pointing us in a certain direction. We just didn’t want to make another limp-wristed LA country-rock record. They were all too smooth and glassy. We wanted a tougher sound.”

For his part, Johns would tell Crawdaddy magazine’s David Rensin, just two days after the split, that “the six weeks in the studio were a disaster area, but I will sit here and tell you that it had nothing at all to do with me. I certainly got frustrated on some occasions, and pissed because they wouldn’t grab the situation by the balls and get on with it. I don’t believe in kid-gloving artists… There were a lot of hang-ups, individually and with each other. But what it boils down to is they weren’t ready to make another record.”

Instead the Eagles returned to LA with only two songs from the British sessions: Best Of My Love and You Never Cry Like A Lover. Around the same time, at the instigation of Henley and Frey, the band parted ways with manager Geffen and his partner Elliot Roberts, and joined forces instead with former Geffen protégé Irving Azoff, who had already gained significant management skills with Dan Fogelberg and Joe Walsh.

Over the course of his career, Azoff – a man dubbed The Poison Dwarf due to both his diminutive stature and his take-no-prisoners attitude – would wear almost every hat an entertainment mogul can possibly wear: record label president, movie producer, agent, concert ticket broker. But his bond with the Eagles – which lasts to this day – has been his most consistent union. He would be instrumental in the band’s drive to world domination. “He may be Satan,” Henley once said, “but he’s our Satan.”

Back in LA, the band hired producer Bill Szymczyk to take over production on the album that would become On The Border. The producer had previously worked on albums with strong rock pedigrees, including J Geils, Jo Jo Gunne and especially Joe Walsh (both solo and with his old band the James Gang). Henley and Frey thoroughly believed that Szymczyk – who also originally brought Don Felder into the mix – was just the man to give the Eagles the rock edge they craved.

“We just wanted to sound American instead of English,” Henley said at the time. “Glyn thought we were a nice semi-acoustic band, and every time we wanted to rock’n’roll he could name a thousand British bands that could do it better.”

Even at the time, it seemed like the Eagles did protest too much about the whole ‘rock’n’roll’ thing. Their repertoire was – and is – ballad-heavy. In fact they would later count on Joe Walsh’s own back catalogue to bring that rock’n’roll oomph to their live shows – Rocky Mountain Way, Funk 49 and Life’s Been Good essentially became Eagles songs.

Yet ironically, On The Border proved to be the Eagles’ most consistent and – some would say – best album. It was also the last album of theirs to feature a hodge-podge of styles from an array of outside writers and collaborators, including Jack Tempchin (who contributed the rousing album opener, Already Gone), Jackson Browne (James Dean, the album’s most rocking track), JD Souther (Best Of My Love, in collaboration with Henley and Frey), and even Tom Waits (a cover of Ol’ 55, from Waits’s debut album, Closing Time).

Bernie Leadon contributed one of the album’s finest moments. My Man was a tribute to his late friend Gram Parsons – although in subsequent interviews Henley claimed that the song was also about Duane Allman, even though Leadon has never made any such claims about the song himself. In subsequent years it has been suggested this was just a tacky way of posthumously getting back at Parsons for the latter’s “dry-fuck” comment.

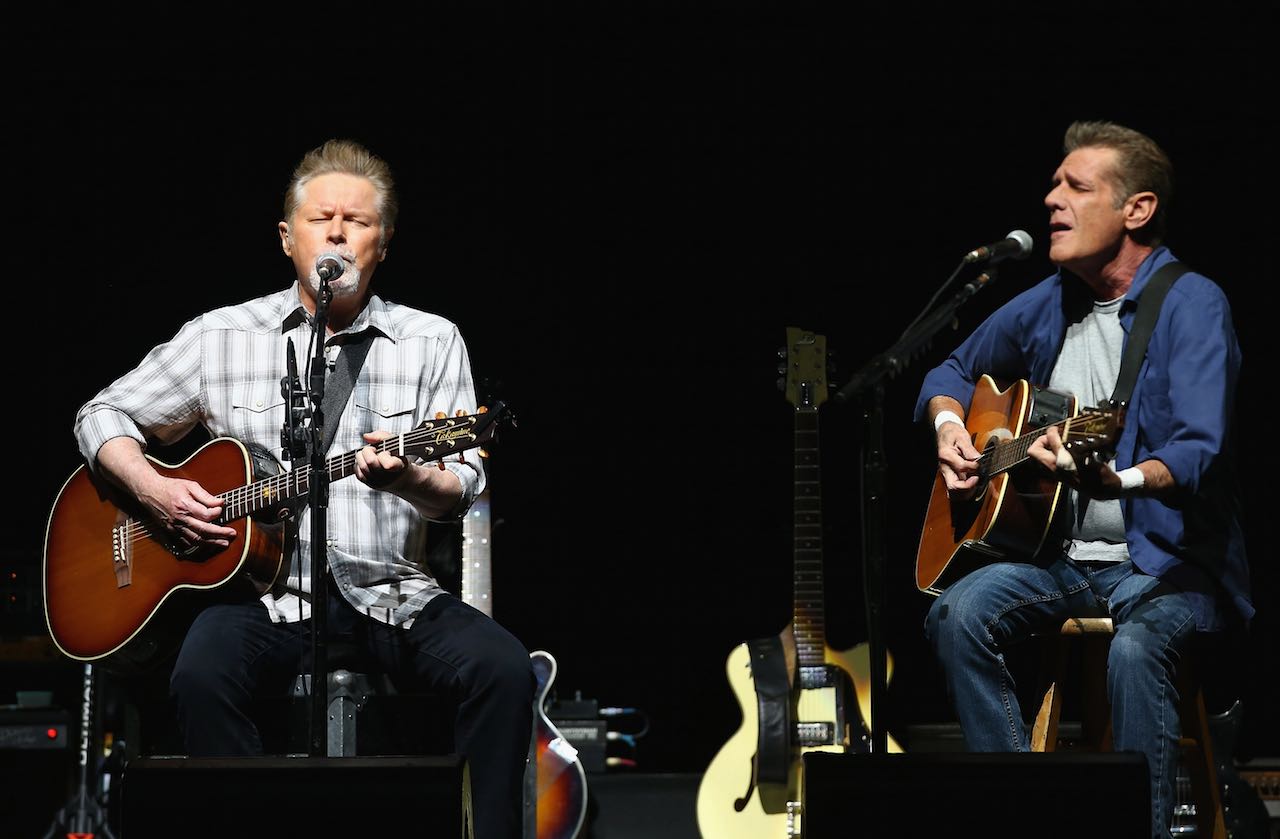

In 1974, Henley was still describing the Eagles as a musical democracy. Within a year, though, things would change, with the drummer now describing himself and Frey as the “leaders” of the group, admitting that some saw them as “dictators”. Unlike many contemporaries, the pair never shied away from describing what they did as a formula. Bob Dylan once said that the first rule of being subversive was not letting anyone know you were being subversive. The Eagles always made it clear that there was nothing “subversive” whatsoever about them.

“I was determined to make it,” Henley told Phonograph Records Magazine in 1975. “The music thing, when all is said and done, it is a business. It’s a weird combination of art and dollars. The opportunities are there, but if you’re not smart you’re gonna get ripped off. It’s as simple as that. Rock’n’roll is a business. Rock’n’roll music is marketed like deodorant or detergent. Of course it has to be marketed, or the masses would never get to hear it, but sometimes it’s hard to keep the art and the business separate. Sometimes it’s hard to remember we are primarily musicians and songwriters.”

Few bands were ever that brutally honest about the intentions behind their music. So when the Henley-sung Best Of My Love became the first Eagles single to hit No.1 (the song was a collaboration between the drummer, Frey and JD Souther), it’s not hard to surmise that Henley and Frey saw its success as both an omen and a chance for them to take control of the group.

Bill Szymczyk was back in the producer’s chair for the follow-up album, One Of These Nights. Recorded through late ’74 and into ’75, it was the work of a well-drilled band. Frey’s comments about the album in the liner notes to 2003’s The* Very Best Of The Eagles* collection were telling.

“There’s no doubt in my mind that One Of These Nights was the most fluid and painless albums we ever made,” he said. “A lot of things came together – our love of the studio, the improvement in Don’s and my songwriting. We made a quantum leap with [the song] One Of These Nights. It was a breakthrough song. It is my favourite Eagles record. If I ever had to pick one, it wouldn’t be Hotel California. It wouldn’t be Take It Easy. It would be One Of These Nights.”

Despite Henley and Frey’s public proclamations, there was a still a vestige of democracy in the group, with all five members contributing. But even though it featured what would become three of the band’s signature hits – the title track, Lyin’ Eyes and Meisner’s epic Take It To The Limit – the rest of One Of These Nights was a mess. Even Leadon didn’t come out unscathed: his contributions to the album included Journey Of The Sorcerer, of which the best that might be said is that it’s a waste of good banjo, and the closing I Wish You Peace, co-written with his then-girlfriend Patti Davis (daughter of future US President Ronald Reagan), which still sounds like bad lounge music to this day.

None of this prevented One Of These Nights from reaching No.1 in the US when it was released in June 1975, such was the Eagles’ momentum. It’s their second-worst album, after 1979’s The Long Run, which practically made turning throwaway, half-baked songs into an art form, but it put their career back on the rails and set up everything that would come next.

Bernie Leadon, for one, had already started to sour on the band. He had begun thinking about leaving the fold during the problematic sessions for On The Border 18 months earlier, uncomfortable with the more mainstream, heavier rock direction the band were pursuing.

“To Bernie, success on any scale was synonymous with selling out,” Henley explained in the History Of The Eagles documentary. “He really wanted us to remain sort of an underground band.”

Matters weren’t helped by personality conflicts. Henley and Frey’s egos were growing along with their success; the latter especially came across at times as more of spoiled frat boy than as a ‘countercultural’ rock star. Both seemed to delight in comparing what they did in their music to “getting off” – that is, an orgasm. Something that made them perfect, if somewhat unselfconscious reflections of the narcissistic 70s. Frey and Leadon in particular began butting heads more and more.

Tensions would reach a head at the end of the One Of These Nights tour, when Leadon infamously poured a whole bottle of beer on Frey’s head following a show at Miami’s Orange Bowl, telling his nemesis: “You need to chill, man!” That was that. Leadon was out, and Joe Walsh would soon be in. Henley and Frey – by now the de facto leaders – said in interviews that if one had to choose between Joe Walsh and Bernie Leadon, well…

Shortly after Leadon left the Eagles, Azoff and the band released the ‘best of’ compilation Their Greatest Hits: 1971-1975. What may have initially been considered a holding pattern unexpectedly turned into a phenomenon: it became the first album to ship platinum (one million units), and in America became the best-selling album of the 20th century, tying with Michael Jackson’s Thriller on 29 million sales.

Next would come Hotel California, a blockbuster album that was to music what Jaws and Star Wars were to movies; Frey and Henley’s increasingly imperial view of themselves and what they’d created; and a three-year gap before the incredibly cynical The Long Run album and tour. By the time the Eagles played the final concert of their original run, on July 31, 1980, they boasted their own management company, their own promotion company and their own booking agency. By that point they were as much a corporation as they were a rock’n’roll band.

Today the Eagles’ legacy is in fine shape. Since their unlikely reunion in the 1990s they’ve become one of the foremost live attractions in the US and Europe. Their musical influence is beyond debate: they’re played on classic rock radio stations as much as, if not more than, any other band; they’re no less of a touchstone in the world of country music (Don Henley recently received a lifetime achievement award from the Americana Music Assocation in Nashville, while his new solo album, Cass County, harks back to his Texas roots); they’ve been covered by everyone from smooth-jazz singer Diana Krall to arch synth-pop types Chromeo.

But the approval that all musicians ultimately crave evades them. Darian Sahanaja – a sideman with Brian Wilson, unarguably the founding father of Californian rock – recently gave an illuminating anecdote to the Colorado Springs Independent. Sahanaja and Wilson were in their dressing room at a fundraiser in New York when Henley and latter-day Eagle Timothy B Schmidt walked in.

“Don was kind of aloof and walking around the room,” said Sahanaja. “And finally, after a few minutes of chatting, Don pulls out a copy of Pet Sounds on CD that he wants Brian to sign. So Brian grabs it and he signs: ‘To Don, thanks for all the great music’. And he’s handing it back to Don, but before Don can take it he grabs it back he crosses out ‘great’ and puts ‘good music’. The thing is, there’s no irony there. He’s not being funny, he’s really thinking: ‘I wrote “great”, but I don’t think it’s great. But it’s good. It’s good music.’ And he handed it back to Don. And it was perfect.”