A professional musician since his teens, after filling roles vacated by violinist Darryl Way and keyboardist Francis Monkman in Curved Air in 1973, multi-instrumentalist Eddie Jobson went on to work with Roxy Music, King Crimson, Frank Zappa, UK and Jethro Tull. During the 80s he was even recruited to Yes, appearing in the video of Owner Of A Lonely Heart, despite not having played or recorded a note with the band.

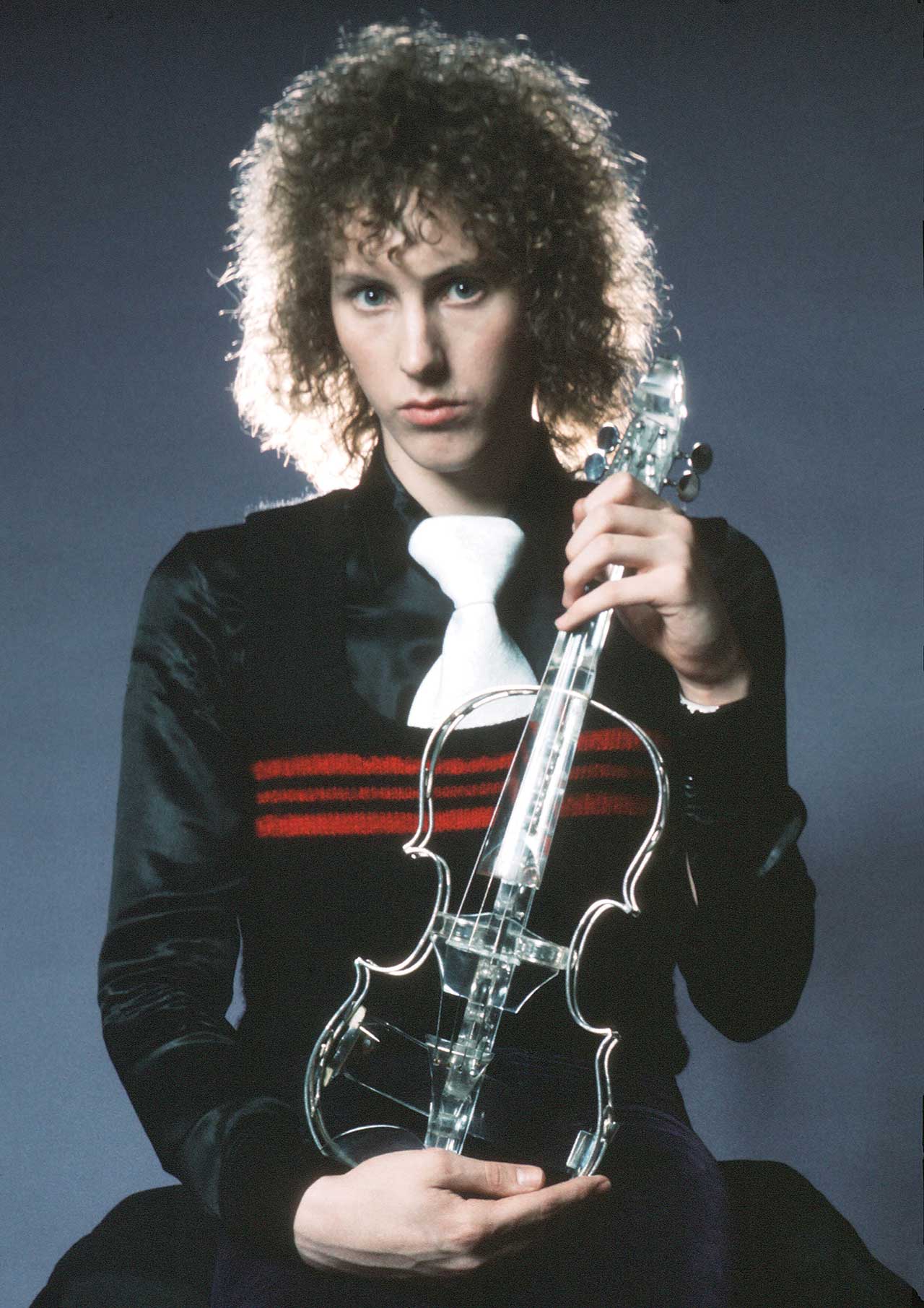

After releasing his celebrated solo record in 1983, Zinc – The Green Album, on which he also sang lead vocals, he went on to enjoy a career as a producer and composer of numerous film and TV scores.

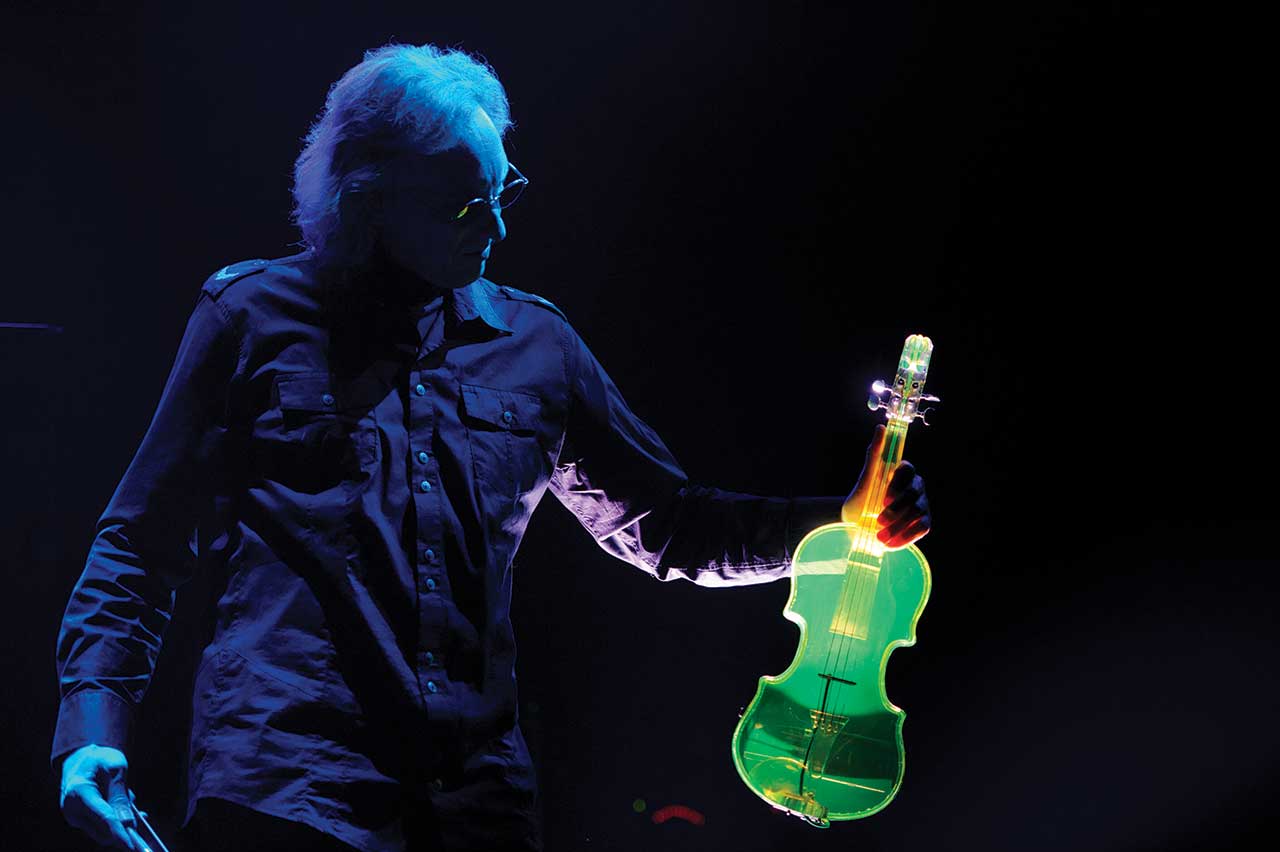

In 2008 he returned to gigging, guesting with artists as diverse as Patti Smith, Fairport Convention and various King Crimson members, going on to reform UK in 2012 for a series of live dates with John Wetton and a career retrospective tour celebrating his four decades in 2013.

Given all this, it’s no surprise Jobson was presented with a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Progressive Music Awards in September 2017. Just before attending the ceremony, Jobson talked to Prog about some of those achievements.

How did your parents react to you becoming a rock musician?

They always thought I would be a classical musician. At first, they were unsure about what I was doing, but once I made my first album with Curved Air, they were onboard. My dad was a member of the local arts council and used to bring classical orchestras to my home town, as well as playing piano himself. He broadened his range of music appreciation considerably once I became a rock musician and a synthesiser player.

You were denied entry to the Royal Academy Of Music because you were too young. Do you ever wonder what might have been if you’d entered the Academy?

I’m not sure how long I would have lasted as an orchestral violinist. I suspect I would have striven to become the orchestra’s conductor and almost certainly a classical composer.

How did you cope with replacing someone like Curved Air’s Darryl Way? Did you have doubts?

The hard part about replacing a major character in any band isn’t the ‘playing’ part: you can either play the parts or you can’t. It’s more about stepping into the shoes of a beloved personality who likely has considerable stage presence and substantial performance abilities.

Before the age of 22, I had to step into the roles held by Darryl Way, Francis Monkman, Brian Eno, Jean-Luc Ponty and George Duke, and you always feel like you’re going to be a disappointment to some in the audience. It’s why I turned down the Yes gig in ’74. Replacing Rick Wakeman at the peak of his silver-caped solo career, at the age of 19, was one too many giant personalities to try to replace.

But no matter who you have to fill in for, all you can do is bring your own musical personality to the band and try to win people over. That’s always been my approach: sometimes you succeed and sometimes you don’t.

What were the best and worst parts about being in Roxy Music?

Being a teenager in the middle of ‘Roxymania’ was very exciting. Also, contributing to such a stylistic change in music, one that has influenced so many other bands, was wonderful. But probably the best thing for me was the world travel, especially to the US, where I’ve lived since the 70s. Not sure if there is a ‘worst’ part… maybe it’s this decades-long sense that my own musical and stylistic contributions to Roxy remain mostly under-recognised.

Is there a Roxy Music studio track you’re particularly satisfied with?

I would pick two: Song For Europe and Out Of The Blue. I think I influenced the sound and style of those two songs more than any others, with the possible exception of my only compositional contribution: She Sells.

John Wetton once said the problem with UK was that neither management nor record company knew what to do with the band. What’s your perspective on UK in the late 70s, particularly with regard to the tensions between you and John at the time?

I would say, in general, that managers, agents and record executives only know how to sell their artists on the back of a hit song or by milking some established brand name. They really have no idea what to do with an uncommercial ‘musician’ band. However, John spent a lot of time socialising with record-biz types, so he was much more tuned in to their commercial and financial aspirations. In contrast, I left Zappa’s band to co-form an offshoot of King Crimson because Robert Fripp was initially meant to be in the later-named UK group, and expected to be playing dark, complex, instrumental music, with perhaps a few uncommercial songs thrown in. We now see, of course, the balance of tastes in both versions of UK play out as it did.

In retrospect, John’s great talent of finding a melodic vocal line over the most unusual, even dissonant instrumental tracks was probably quite helpful in us reaching the level of popularity that we did acquire, which at the end of the day was a positive thing. We still didn’t really have a hit pop song, thank goodness, but it at least gave the record companies something to work with.

You’ve worked with bandleaders known to have a very strong vision about their music – Ferry, Zappa, Ian Anderson. What, if any, are the qualities they share with one another?

All three are not only unique individuals in almost every respect, but they all had the fearlessness to risk ridicule. They could have been laughed off the stage in their early days, but went out and unflinchingly embraced their almost shocking originality.

Bryan, Frank, and Ian have become iconic characters not just because of their talents and vision, but because they had the audacity to live out their own eccentricities in public. John Lennon, Elton John and David Bowie are all people who have done that and become cultural icons in the process. You have to admire that. Amazing, really.

What would you say is the one thing you’ve learned from them?

Ha! Well, one thing I have not learned is how to become a cultural icon. That’s clearly not something that’s in the cards for me! But what have I learned? I would say that Bryan, Frank and Ian helped to reinforce the idea that when you know who you are, and what you’re meant to be doing in life, you have to stick with it through all of the resistance and adversity that will surely come your way. Persistence, bloody-mindedly sticking to your direction and to your standards and values, regardless of the naysayers and the trend-mongers.

One of the keys to having a long career in music, or probably in any field, is to develop your own unique qualities as far as you can and come to represent something. Try to be distinctive; become the recognised standard for what it is you do.

How would you describe yourself: are you a control freak or more easy‑going?

Probably both. I’m quite easy‑going on financial and life issues, but quite the control freak on projects.

Is being a control freak your way of escaping the politics that comes with being in a band?

Absolutely. I have a renewed appreciation and can relate much more with my former colleagues like Bryan, Fripp, Zappa and Ian Anderson now that I’ve been a bandleader myself. It does seem quite necessary to control every aspect of a group’s activities to keep the band’s identity and career on track. So yes, I think the benevolent dictatorship model lends itself to a more focused vision than the democratic committee way of doing things.

The downside is that you become easily mischaracterised as somewhat tyrannical, but that can’t matter. I’ve always believed that real quality resides in the details, and that attention to detail is best realised within the purview of a single bandleader.

Zinc – The Green Album, released in 1983, seems such a special point in your overall catalogue. How do you view it today?

You know, it’s interesting looking back at it. That was the last prog album I made before leaving the record business for a substantial amount of time. I suspect it was just about the only progressive rock project newly signed to a major label in the 80s. But because I left the rock world after that and didn’t perform live again for another 26 years, I never received any feedback on the impact of that album.

It wasn’t until I returned to the stage in 2009 that I found out how well-regarded that album was in the prog community. Even Chris Squire told me it was one of his all-time favourite albums! So that has been something of a surprise and obviously makes me quite proud of the accomplishment.

It was a very difficult record to make, mostly in the funding department, and I couldn’t find the right musicians, having just moved permanently to the States. I also couldn’t find a singer, so reluctantly took on the role myself. But in hindsight, that’s okay. If anything, it makes it even more of a solo album.

What’s the key track for you?

Resident, I think, best captures musically and sonically what I was trying to do. I started The Green Album in 1980 with the goal of reinventing my own style of progressive rock, but with a fresher, new 80s sound. I deliberately avoided using the Hammond and focused instead on trying to find new timbres on just the CS80 and Minimoog. Sampling technology wasn’t available to me yet.

There was talk it was going to be followed up by The Pink Album. What happened to that?

It was never made but two members of Glass Hammer, Fred Schendel and Alan Shikoh, have just made their own version of it, in the style of The Green Album, under the band name CZ-101. Yes they are actually calling it The Pink Album.

What’s the moment or piece of music in your career that you feel most proud of?

Obviously, my work with UK stands out. However, right now, I would say I’m particularly pleased with the piano improvisations recorded for the Zealots Lounge. I’d never done anything like that before, so I had no idea what was going to come out. I also like the work I did with the Bulgarian Women’s Choir back in 2000.

Those piano improvisations are an interesting departure. To what extent are you able to completely let go, or do you have to have a framework as a starting point?

It was literally a three-and-a-half-hour stream of consciousness in musical form. To say I was in a zone would be an understatement. They were broken up into 21 10-minute compositions that were sold to individual sponsors as part of a crowdfunding campaign to help fund the UK Ultimate Collector’s Edition box set.

How do you maintain your chops? Do you have a routine?

To be honest, I rarely play. I was lucky enough to have a piano teacher who gave me some excellent technique pointers when I was about 14. It also helps that I have a large span and very strong fingers, so I usually only have to play for a few days or maybe a week before a tour to work out the stiffness.

You appeared on one of the first progressive rock cruises in 2014. What are the pros and cons of performing live on the high seas?

Ha! Well, as I said on the second cruise, “We always feared that our careers would end up playing on cruise ships!” But actually, the prog cruises are quite good fun, if you can deal with the occasional motion. Unfortunately, we got a little unlucky with the weather on both of our cruises. But the fans are great, and it was nice to spend time with some of my fellow prog veterans whose paths I hadn’t really crossed before: Steve Howe, Patrick Moraz and Carl Palmer are all people I’ve come to know from the cruises.

Much of the music that came out of the 60s and 70s seems incredibly innovative and without precedent. It’s regarded as something of a golden age. What’s your take on that time?

Looking back on the 70s in England, there was undoubtedly a progressive musical culture that energised itself. We were all pushing each other to higher levels and were inspired by the originality of the other musicians in the studio next door, or the groundbreaking albums being produced around us.

You see this kind of thing throughout history, from the Renaissance to Motown and all the way to Silicon Valley, where a community competes, feeds off and inspires itself. I’ve always believed it’s a certain cultural freedom that allows for such free thinking and innovation. You tend not to see that kind of thing coming out of repressive cultures and dictatorships.

On the business level, I think that the managers, lawyers and accountants back then mostly knew how little they understood about music and left the art up to the artists. Their job was to market what the artist produced; the artist’s job was to create something worthwhile and not worry about whether it was going to sell or not. After The Beatles, the whole point was to be original and innovative: most bands were trying to create their own distinctive sound and style.

Unfortunately, that all started to change in the late 70s as huge profits were being generated in the music business. That’s when the genius businessmen fully took over and generally viewed originality as too risky: ‘Why take a chance on this new thing when we can replicate the successful formula that made us a fortune last time?’

By about 1980, certainly in the US, that hands-off approach to the music was pretty much over – the record execs and their golden-eared wives who could always “hear a hit” took control of the creative process to a seriously destructive degree. So I’d say that the music in the late 60s and 70s was innovative simply because it was allowed to be. Freedom and passion drive innovation; money drives replication. You can quote me on that.

Are concert promoters also unwilling to take a risk on bands these days?

It’s not so much that they aren’t interested in my music, it’s that they don’t know if there’s an audience that will show up to hear it. I had the same issue on the UK reunion tours. When a band hasn’t performed together in some 30 years, there’s no track record of ticket sales so any concert is considered financially risky. I ended up renting the venues and promoting quite a few of the concerts myself – New York, Los Angeles, London, even Tokyo. If I can’t find a willing promoter, I just do it myself.

Given the breadth and range of your career, have you ever considered writing your autobiography?

That has been suggested to me so many times. I would certainly have enough material. I could probably fill a book just from my inside stories of Roxy Music and Frank Zappa, but I’m much more interested in writing a symphony than an autobiography. I’m also thinking about making a series of educational videos on the art and science of music, hopefully in the next year or so before I forget everything I know about the subject!

It’s interesting you mention writing a symphony. There are a few rock players who have worked in that idiom. Is it something you plan to do?

Part of my hesitation in even thinking about entering the classical field as a composer is that the folks in that world strike me as being quite smug in their intellectual elitism. In my opinion, it will take some letting go of those academic pretensions if classical music is to move forward with any contemporary relevance. But hey, that’s just my view.

What were the challenges you encountered when you were scoring for television, film and advertising?

The biggest in all of those fields are the pressures of the deadlines, not to mention having to deal with some very difficult personality types. Once, for an American TV pilot episode, I had to write and produce 50 minutes of original score and eight heavy metal and hip-hop tracks – three of them with vocals – all of it in 48 hours, without sleep.

I used to be quite energised by those high-pressure challenges 20 years ago when I first started working in Hollywood, but it’s not something I could deal with any more.

The upside to stepping away from the intensity of that world though was that I was more motivated to get back into recording and ultimately to touring again, after such a long hiatus. The last five world tours and three box sets were only possible because I closed down my scoring career.

How do you relax away from your music career?

I used to cycle – I rode an Italian handmade De Rosa. But my wife and I are big foodies, so nowadays you’ll more likely find me sitting in a nice restaurant somewhere. I also watch an inordinate amount of political television, especially late at night. The thing that relaxes me the most is listening to other people trying to sort out the world’s problems.

What’s the best advice you’ve received personally or professionally?

When I was young, I received what might have been the best advice at the time: get a real job and keep music as a hobby. Fortunately, I completely ignored them.

See www.zealotslounge.com for more information.