In late April 1972, Led Zeppelin decamped to Stargroves, Mick Jagger’s Berkshire mansion, to start work on their fifth album. According to Robert Plant, it was a chance for Zeppelin to show another side to their personality. “It’s time that people heard something about us other than that we were eating women and throwing the bones out of the window,” the singer said at the time.

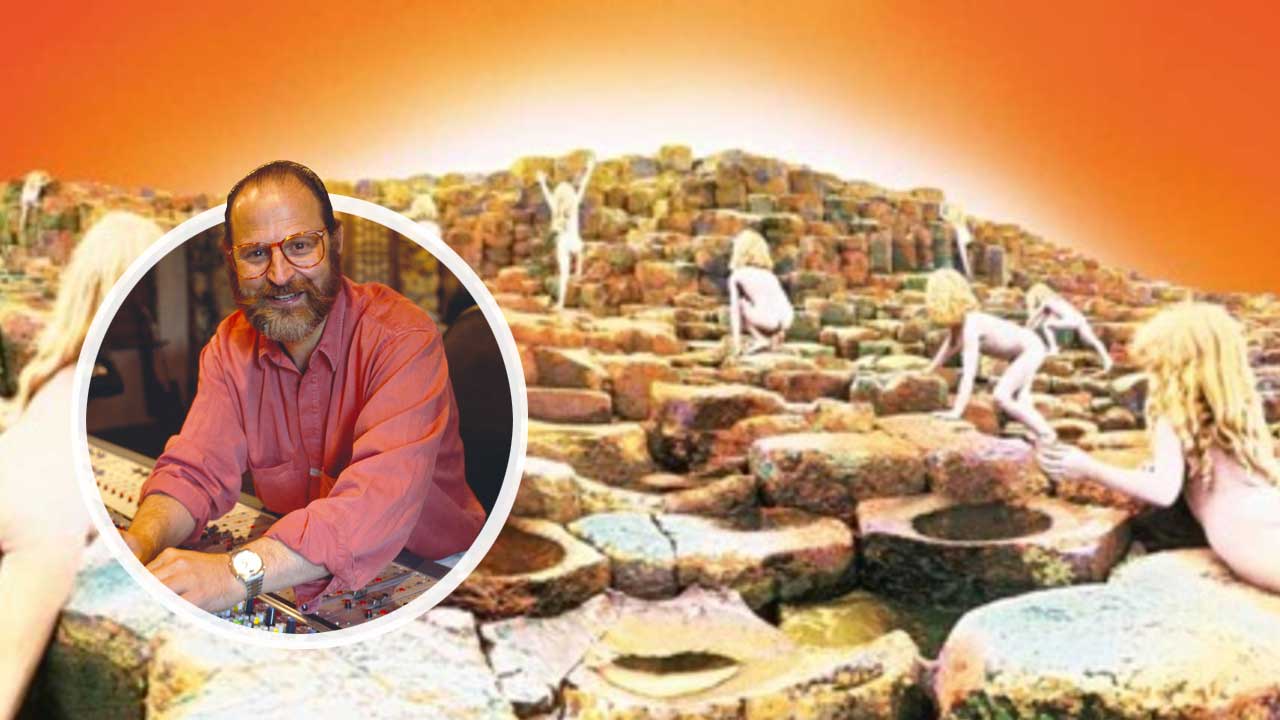

The man they initially brought in to help them get their goal on tape was renowned South African-born producer/engineer Eddie Kramer. Kramer had worked with Zeppelin on III, on which he was credited as ‘Director Of Engineering’, although his most recent encounter with the band had ended badly following a row during sessions the previous year at Electric Lady studios in New York.

“Everything was going fine until they ordered in some Indian food,” says Kramer today. “A whole bunch ended up on the floor. I was pretty possessive about the place and I asked them to clear it up. And they all walked out!”

All that had been forgotten by the time Kramer got the call to fly to England to work with Zeppelin again. When he arrived at Stargroves, the band were in buoyant mood. “The weather was good, the atmosphere among the band was very jolly,” he says. “Jimmy had Jagger’s bedroom. Everyone was happy.”

The Rolling Stones Mobile truck would be used to capture Zeppelin at play. Kramer saw his role as “helping them achieve whatever sounds Jimmy wanted. He was the boss, very clearly.”

Kramer assisted Zeppelin to record eight tracks at Stargroves, four of which would end up on the album. (Three of the others – Black Country Women, The Rover and Houses Of The Holy itself – would appear on the next album, Physical Graffiti, while the final track, Walter’s Walk, surfaced on the posthumous collection Coda, released in ’82). He also mixed many of the tracks that made up Houses Of The Holy.

“These days, bands want it so perfect that they miss the magic that a band like Led Zeppelin had,” says Kramer. “You’ve got to leave all the hair in. It’s rock’n’roll.”

Read more about the making of Houses Of The Holy in the new issue of Classic Rock.

The Song Remains The Same

The latest in a string of classic Zeppelin album openers. Prior to album sessions, this song was rehearsed with the working title Worcester And Plumpton Races – a reference to Page and Plant’s respective homes. When they worked on it in the studio, that title was changed to first The Overture and then The Campaign. It was only when Plant started scribbling verses for it that it ceased to be an instrumental and became his paean to the music of the world, whatever form it takes.

“The whole album had a very upbeat quality to it,” says Kramer. “You can hear that straight away from this opening track. A much brighter sound than on earlier Zeppelin albums. There was a unity of spirit and a unity of direction of sound. A lot of that had to do with Pagey and the fact he had a very clear idea of what he wanted. I believe Jimmy later had Robert’s vocals speeded up a bit so that they become another layer to all those gorgeous guitars.

The Rain Song

If there’s one Zeppelin song that unites people in its greatness, then it’s this smouldering, otherworldly epic. Page wrote it in response to a conversation he had with George Harrison, in which the former Beatle asked why Zep never did any ballads.

Working on demos for the album at his Plumpton studio, Page came up with this epic-in-waiting with the tongue-in-cheek working title Slush – incorporating a subtle use of the opening notes of Harrison’s Something into the arrangement. At one point it was intended to have been a further extension of The Overture, but that changed when Plant added lyrics and it was retitled The Rain Song.

“I love this track because of the typically esoteric Pagey guitar tuning, but also because of the role John Paul Jones plays on it,” says Eddie Kramer. “This was definitely the album where Jonesy finally stepped out of the shadows. I knew him from before Led Zeppelin, when he was a session musician.

"He was a superb arranger who could conduct an orchestra while playing bass with one hand. I once saw him do that. That Mellotron he plays on this is what lifts the track to another emotional level. And the piano, which he also plays, is like raindrops, or maybe teardrops. I don’t think they’d ever done a track so subtle before. That’s the test of a great arranger: to do something so subtle yet which has such power. Quite beautiful.”

The Crunge

One of two tracks on the album that splits the vote with fans, this knockabout tribute to James Brown was something that Jimmy Page had been tinkering with since 1970.

“This is one of those tracks that sounds like it just started completely off the bat as an impromptu jam in the studio,” says Kramer. “But what you quickly learn about working with musicians of the calibre of Led Zeppelin is that nothing is ever brought to the recording that hasn’t been worked over, in Jimmy Page’s mind at least, to the Nth degree.”

It’s preceded by some studio chat between Page and engineer George Chikianz, who you can hear talking just as Bonham comes in on the intro. The track also has John Paul Jones on a pioneering EMS VCS3 synthesiser.

“Of course, it is a fantastic jam, with Bonham and Jonesy especially really going to town. But the tension is very tightly held. I’d set Bonzo’s drums up in the conservatory, and the sound he got in there was phenomenal. But they all knew what they were doing.

"And I love all that James Brown stuff Robert does about taking it to the bridge, because of course there is no bridge in this track. Hence the in-joke ending: ‘Where’s that confounded bridge?’” There was even an idea to include some dance steps on the sleeve as a guide for happy-footed Zeppelin fans. Wisely, the idea was scrapped."

Over The Hills And Far Away

Another feature of the album that Kramer identifies is how most of the tracks have their own boutique ending: the orgasmic ‘Oh!’ at the end of The Song Remains The Same; the echoing guitar at the climax of The Rain Song. Over The Hills And Far Away (originally titled Many Many Times) finishes with a similar coda, created by Page using a reverb guitar effect with Jones’s keyboard part.

“I can’t remember exactly, but I think it was something I suggested at the mixing stage,” says Kramer. “I used to do something similar with Hendrix sometimes – fade the track out, then bring it back, like an extra breath.” What really makes this track, though, he says, “is that it really shows off the Zeppelin preoccupation with light and shade, acoustic and electric”.

Dancing Days

One of the great overlooked Zeppelin rockers. The seeds of this track went back to a visit Page and Plant had made to India the year before, for a date Jimmy had arranged with a collection of musicians in Bombay, recording rough-and-ready versions of Friends and Four Sticks. The snake-hipped riff and slouching melody were inspired by a raga they overheard at a wedding during their stay.

“By the time they started playing the track with me, it just had the most amazing vibe,” Kramer recalls. “Just a glorious groove. They all enjoyed playing it so much. The way Bonzo played it was what really made it, though. He just found a way to make the rhythm bounce and snap.

"I’ll never forget playing it back to them from the mobile truck and how excited they all were. It was a lovely sunny day, and there was Jimmy and Robert and a couple of others all sort of linking arms and dancing on the lawn. I don’t think even they could believe how good they sounded.”

D’yer Mak’er

The title might have been filched from an old music-hall joke (‘My wife’s gone to the West Indies…’ etc), but the song was originally Plant’s attempt at a 50s doo-wop pastiche. He was keen to release the reggae-tinged track as a single – Atlantic even distributed promo copies to DJs – but not everyone was so keen on it. John Paul Jones was vocal in his derision of the track.

“A real love it or hate it track, which I still love,” says Kramer. “Those huge drums that kick in at the start are like bombs going off. What’s amazing, though, is how John Bonham keeps the bombs going off while playing this extraordinarily subtle and brilliant rhythm. Robert’s voice is also superb, kind of a meeting of doo-wop and reggae.

“All credit must also go to Jonesy, whose bass takes the reggae rhythm to a whole different place. I could go on about this one for hours. Suffice to say nothing like it had ever really been attempted by a rock band before, and it caused a lot of controversy when people first heard it.”

No Quarter

The only studiedly ‘down’ track on the album was first tried out at Headley Grange during sessions for Zeppelin’s fourth album, at which time it was much faster than the final versions. On Houses Of The Holy it was John Paul Jones’s personal showcase.

“This was the album where Jonesy really came into his own, and this is the track that proves it,” says Kramer. “I wasn’t there when they finally recorded it, but they had demo versions of it going back a few years. It really demonstrates that Led Zeppelin could do anything they turned their minds to now – and do it better than anybody else.

"They were able to really stretch out now and experiment, which allowed the space for Jonesy to come in and do his thing on the arrangements. It wasn’t just his brilliance as a keyboard player or even a writer, it was also the subtlety of his arrangements, and the economy of notes that made this track such a powerful statement. Genius.”

The Ocean

Already part of the band’s encores long before it was released, the album’s closing track was Plant’s ode to Zeppelin’s legions of fans. John Bonham counted in the song with the words: “We’ve done four already but now we’re steady and then they went one… two… three… four…” – something which became a ritual when it was played live. Listen carefully and you can hear the studio telephone ringing in the background at around 1.37.

“This was another one where Bonzo’s drums just sound amazing,” says Kramer. “Some of the stuff Jimmy asked him to do in Led Zeppelin… it was complicated shit, and Jimmy would have to run through it with him a few times. But once he locked in, once he knew precisely what he had to play, then he would fuck with it and blow your mind, put a fill where you would not expect it. We’d all be laughing because it was just so insane.

"But we were going for ambient sound, so we utilised every aspect of the house and its grounds we could. I remember putting a Fender amp in the fireplace and putting a mic up in there. Jonesy’s bass was in another room. Everybody’s gear was in a different room. There was no CCTV, but I put talkback mics all around so people could yack to each other.”

The new issue of Classic Rock tells the story of Houses Of The Holy: How it split fans, but signposted the way forward for a band now operating at their peak. It's available to buy online and in UK stores now.