The godfathers of heavy metal were starting to feel their age. 1978 was supposed to be a year of celebration for Black Sabbath – their 10th anniversary - but in reality, the group was falling apart. “The fun of being in a rock band was dwindling for me,” Ozzy Osbourne later admitted. “I don’t think anyone’s heart was in it anymore.”

Ozzy had actually taken a leave of absence from Sabbath in autumn ’77, officially to spend time with his father Jack, who was dying of cancer. When NME interviewed the singer in November ’77, he seemed in no mood to return to the unit - “I just want a simple life for a while,” he insisted – and when Sabbath performed War Pigs and Junior’s Eyes on BBC TV’s Look! Hear! programme in January 1978, former Fleetwood Mac frontman Dave Walker stood centre-stage between Tony Iommi and Geezer Butler.

So it was something of a surprise when the singer returned to the fold ahead of the Birmingham band’s departure to Toronto to record their eighth studio album, Never Say Die! Though old tensions occasionally surfaced during fraught studio sessions – “we were all fucked-up with drugs and alcohol,” Ozzy recalled – all four musicians were excited about the prospect of returning to the UK for their 10th anniversary tour in May.

Sabbath had taken AC/DC out as support on their last run of European gigs, and had struggled to match the livewire Aussies for energy, so Ozzy instructed Sabbath’s booking agency to find “a bar band from LA” to open the show each night on their homecoming dates. As luck would have it, their US label, Warners, had just such an act on their books.

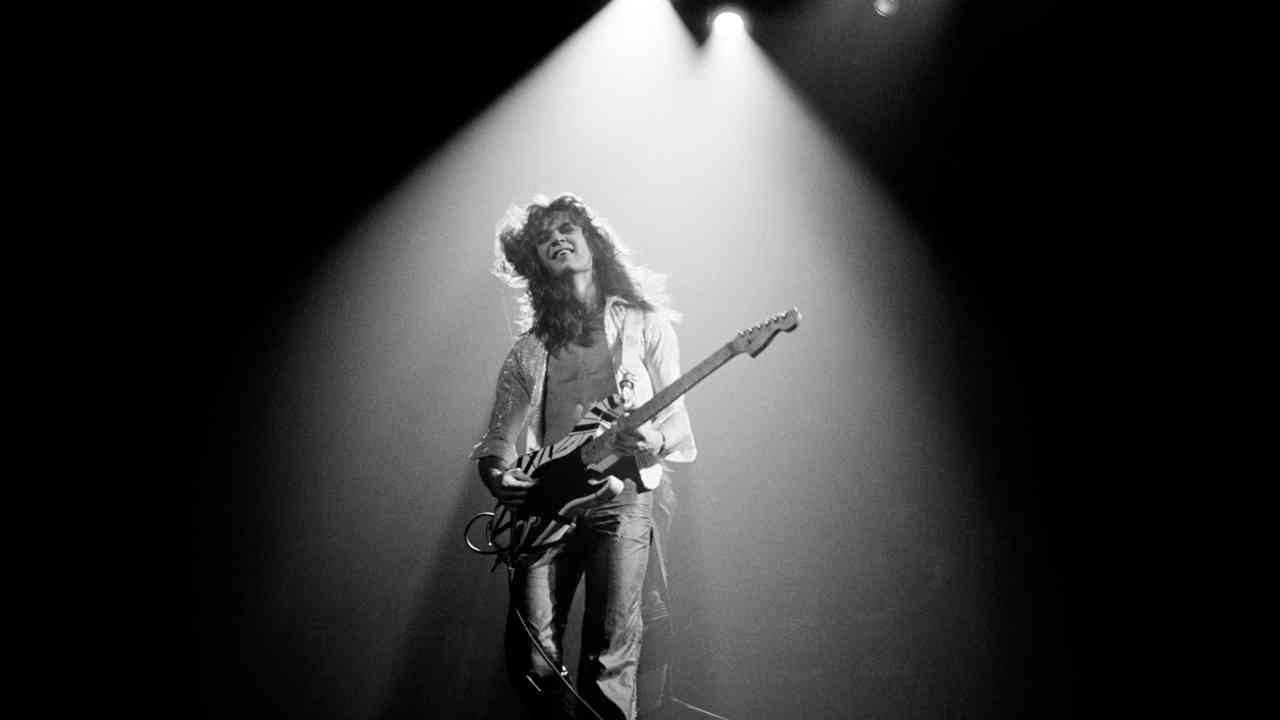

The name Van Halen meant nothing to the members of Sabbath, so, out of curiosity, ahead of their scheduled stage time on the tour’s opening night at Sheffield City Hall on May 16, Ozzy and his bandmates Tony Iommi, Geezer Butler and Bill Ward, shuffled out of their dressing room to catch the end of the Californian band’s set. They arrived side-stage just as the group’s guitarist, 23-year-old Eddie Van Halen, launched into the second track of his band’s recently released self-titled debut album.

Eruption wasn’t originally on the list of songs Van Halen had pencilled in to appear on their debut. Producer Ted Templeman had popped out of the control booth at Sunset Sound Recorders to grab a coffee when he first heard Eddie Van Halen playing the 102-second instrumental between takes. “What’s that?” Ted asked. “Ah, nothing,” came the reply. “It’s just something I warm up on.”

“Let’s hear it again,” the producer said. “We gotta record it. Right away.”

- Eddie Van Halen – the 1978 interview

- Top Ten Covers Van Halen Made Their Own

- The 50 best guitarists of all time

- The 50 best rock bands of all time

Eddie Van Halen had been finessing his solo showcase onstage in Hollywood clubs for the best part of three years. As often as not, he would perform the classically inspired instrumental with his back to the audience, so that no one could see exactly what he was doing. The secret technique the guitarist was shielding involved using both his hands on the fretboard to tap out notes at light-speed. Van Halen would later claim that he hit upon the idea while watching Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page play the solo from Heartbreaker one-handed during a show at The Forum in Inglewood, California in August 1971: “It’s like having a sixth finger on your left hand,” he told Guitar World’s Steven Rosen. “Instead of picking, you’re hitting a note on the fretboard. Nobody was really doing more than just one stretch and one note real quick. So I started dicking around…”

Van Halen never claimed to have invented the two-handed tapping technique, but watching him perform Eruption up close before slamming into his group’s swaggering update of The Kinks’ You Really Got Me left the members of Black Sabbath in slack-jawed awe as they trooped back to their dressing room.

“We sat there going, ‘That was incredible…’,” Ozzy recalled, “and then it finished, and we were just too stunned to speak.”

“I didn’t know very much about Van Halen at all,” admits Tony Iommi, “but when I first heard them it was like, ‘Bloody hell!’ They were so energetic, they were great players, they had good songs and we were just like, ‘Wow, blimey, these are really good!’”

When the tour reached London, Iommi collared his good friend, Brian May from Queen, to join him side-stage at the Hammersmith Odeon to watch the hot-shot Californian at play.

“The pair of us watched Eddie Van Halen do his stuff, and it was just glorious,” recalled Brian, “almost too glorious to take in. To see this guy romping around a guitar like a kitten, just running and taking it to places undreamed of… There hadn’t been anything so shocking since Hendrix.”

“The place was packed for Van Halen,” recalls Metal Hammer writer Malcolm Dome, then a journalist for weekly music magazine Record Mirror. “Everyone wanted to see them because they’d already got a real buzz around them from the metal cognoscenti, the people who regularly bought rock records on import. They were definitely better than Sabbath that night; they were so exciting, vibrant and so new, and they made Sabbath look old. They sounded like the future.”

From an early age, Eddie Van Halen was acutely aware of music’s capacity to captivate, charm and bedazzle. As a small child, Eddie would sit enrapt while his father Jan, a professional musician who performed with distinction in jazz bands and orchestras, practised clarinet in the family home in Nijmegen, Holland. On occasion, when his Indonesian-born mother Eugenia was required to work night shifts, Eddie and his older brother, Alex, would be packed off to Jan’s musical engagements, their mother hoping that their presence might inhibit their bohemian father’s predilection for extensive post-gig drinking. In reality, it did nothing of the sort, merely strengthening the duo’s impression of the music scene as a free-spirited utopia. When Edward was five and Alex six, Eugenia enrolled the children in piano lessons with a Russian concert pianist who lived locally. “If you’re going to follow in your dad’s footsteps,” she warned the pair, “it better be respectable.”

In March 1962, the Van Halens left their apartment at Rozemarijnstraat 59 and set off to board an ocean liner bound for America. Letters from relatives in California had fired Eugenia’s dreams of a fresh start for the family. The new immigrants arrived in Pasadena later that month, and took up residence in a modest three-bedroom, single-bathroom apartment they were to share with two other families.

“When we finally arrived in Pasadena, it was rough,” Eddie told an audience at Washington DC’s National Museum of American History, during a February 2015 talk convened as part of the Smithsonian’s What It Means To Be American series. “We lived in one room, slept in one bed. My father had to walk three miles to go wash dishes [at the Arcadia Methodist Hospital], he was a janitor at the Masonic Temple, at Pacific Telephone, my mom was a maid… We used to go dumpster-diving for scrap metal, then go to the scrap yard and sell the metal we found.”

“We were two outcasts that didn’t speak the language and didn’t know what was going on,” he told Rolling Stone, referring to Alex and himself. “So we became best friends and learned to stick together.”

Music would serve as an escapist outlet for the brothers. The success of The Beatles prompted a ‘British Invasion’ of the American ‘hit parade’ in the mid 1960s, and having been charmed by the smooth melodies of London’s The Dave Clark Five, the Van Halen boys formed their first band, The Broken Combs, with Eddie on piano and Alex on saxophone. In time, Eddie switched to learning drums, while Alex began playing guitar, but they would soon swap instruments. “He could play [The Surfaris’ 1963 instrumental hit] Wipeout and I couldn’t,” Eddie later recalled. “I said, ‘OK, fuck you. I’ll play your guitar.’

‘Forget the piano, I don’t want to sit down – I want to stand up and be crazy.’

“My brother would go out at 7pm to party and get laid,’ Eddie told Smashing Pumpkins frontman Billy Corgan in a 1996 Guitar World interview, ‘and when he’d come back at 3am, I would be sitting in the same place, playing guitar. I did that for years.”

In 1971, the Van Halen brothers and fellow teenager Mark Stone formed a power trio named Genesis. With Eddie on vocals and guitar, Alex on drums and Mark on bass, the trio played note-for-note versions of songs by Black Sabbath, Led Zeppelin and Cream. Upon discovering that a rather better-known rock band named Genesis existed in England, the Pasadena trio became Mammoth. In 1974, somewhat reluctantly, they recruited cocksure, Indiana-born vocalist David Lee Roth, formerly with their local rivals Red Ball Jet, to front the band. The Van Halen brothers were more than a little wary of the flamboyant, peacocking, motormouth singer - “Ed and I couldn’t stand the motherfucker,” Alex once bluntly admitted to Steven Rosen, for a Classic Rock magazine piece titled VH: The True Beginnings – but David had his own PA, enough confidence to power the national grid, and a devoted following among Pasadena’s female high school population, so a marriage of convenience was struck.

When Mark Stone was replaced by Chicago-born Michael Anthony Sobolewski, who would later drop his Polish surname, it was David who suggested they rebrand as Van Halen, and supercharge their live sets with more accessible, less technical songs to seduce club audiences. “It’s very impressive,” he said of the group’s old repertoire, “but you can’t dance to it.”

The new Van Halen mission statement, David insisted, would be to make every day seem like a Saturday night. In came hits by Aerosmith, ZZ Top, James Brown, David Bowie, Bad Company, Kiss and Queen. The revamped group quickly carved out a reputation as the area’s hottest good-time band, drawing hundreds of teenagers to their riotous backyard gigs… until, inevitably, cops descended to break up the party. While David had a quick wit, a big mouth, pretty boy looks and a complete lack of shame, it was the shy, permanently smiling guitarist by his side who was the group’s true star, as their peers quickly realised.

“Eddie was pretty special,” recalls Mark Kendall, who later found fame as the guitarist of LA rockers Great White. “I’d look into the crowd and I could see the guitar player from every band I knew watching him. Eddie was the man, the king, it was unquestioned.”

“We were jealous, and we were all trying to play catch-up,” recalls future Dokken guitarist George Lynch, then playing in LA-area band The Boyz. “We thought, ‘Oh boy… this guy’s going to change the world.’”

Word of the band’s snowballing popularity soon reached Los Angeles-based manager Catherine Hutchin, a vivacious, well-connected Londoner who looked after local acts such as Sudden Death, Yankee Rose and Sorcery. Always keen to make useful contacts, David Lee Roth invited Catherine to check out the band at a party at his doctor father’s house.

“When we got to the house, which was in a ritzy area of Pasadena, there were cars parked everywhere, and my assistant Lynore and I had to park quite a way away, and walk over in our platform shoes,” Hutchin, now Catherine Harris, recalls. “We could hear the music from streets away, and when we got into the party it was crazy, absolutely crazy. The first thing that hit me was Edward. He was unbelievable. He was playing with his fingers over the frets, which nobody did then, and I was absolutely blown away. Lynore and I looked at each other and I said, ‘Oh. My. Goodness. This kid is a virtuoso.’ They were kinda just another rock band until Edward cut loose. David was brilliant onstage, but it was Edward who really grabbed us. So I started booking them shows in Hollywood.”

As the de facto house band in Gazzarri’s from April 1974 onwards, Van Halen’s reputation - and word of Eddie’s dazzling musicianship - spread across Los Angeles. But, it was actually George Lynch’s burgeoning reputation as a homegrown guitar hero which drew Kiss duo Paul Stanley and Gene Simmons to the city’s Starwood club one evening in 1976, the duo having been tipped off that Lynch’s band The Boyz were Hollywood’s hottest rock act. By coincidence, Van Halen were booked to play the same night. By now the group’s original material – showcasing a sound they called Big Rock – was eclipsing the cover songs in their high-energy sets, and, when the quartet took to the Starwood stage that night following The Boyz’ set, Stanley and Simmons immediately recognised a raw talent with potential.

“I had gone to the Starwood the night before with Lita Ford and seen Van Halen and The Boyz,” recalls Stanley. “I remember The Boyz covering Detroit Rock City and I was thinking, ‘Boy, this a great song’… and then realised it was mine! But Van Halen were just a powerhouse – Eddie was something completely different, and Dave was on his way to becoming the ultimate frontman. Afterwards Gene snuck up and offered to take them to the studio to do a demo.”

To Simmons’ astonishment, however, on hearing that demo, Kiss’ manager Bill Aucoin decided to pass on taking Van Halen on... a decision Paul Stanley later confessed was more about reining in Simmons’ ambitions than a snub to the Californian band.

On the evening of February 2, 1977, Ted Templeman watched Van Halen perform in front of a subdued Starwood crowd. Formerly a member of ‘sunshine pop’ band Harpers Bizarre, Ted was now a hotshot producer (having worked with Van Morrison, Little Feat and Californian hard rock band Montrose) and A&R executive at Warner Bros. He returned to the club on the following night with company chairman Mo Ostin in tow, and insisted that Warners sign the band on the spot.

“When Van Halen came onstage it was like they were shot out of a cannon… they performed like they were playing an arena, and not a small Hollywood club,” Ted recalled in his autobiography A Platinum Producer’s Life In Music. “Right out of the gate, I was just knocked out by Ed Van Halen. It’s weird to say this, but encountering him was almost like falling head-over-heels with a girl on a first date. I was so dazzled. I had never been as impressed with a musician as I was with him that night. When I think back on that night, it wasn’t just one thing about him that grabbed me. It was his whole persona. This guy, when he played, looked completely natural and unaffected; he was so nonchalant in his greatness. Here he was, playing the most incredible shit, acting as if it were no more challenging than snapping his fingers.”

Ted booked the quartet into Hollywood’s Sunset Sound studios in April. The Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin and The Doors had all used the facility in the past, and Van Halen’s demo sessions would prove to be a breeze, with the quartet recording live, rolling through 25 songs in a matter of hours. Though the perfectionist Van Halen brothers had some misgivings about the results of the hastily arranged session – “We popped it [the demo cassette] into the player in my van and expected to hear Led Zeppelin coming out,” Eddie later confessed to Guitar World’s Chris Gill, “but we were kind of appalled by what we heard. It just didn’t sound the way we wanted it to sound” – they were not about to question Ted’s authority. At the end of August, the group returned to the studio with Ted to cut their debut album.

Put simply, that album, unfussily titled Van Halen, is one of the greatest hard rock albums in history. From the pounding Michael Anthony bassline that introduces Runnin’ With The Devil via the dazzling Eruption and the punchy cover of You Really Got Me (Ted Templeman’s banker for ensuring that Van Halen, unlike his former charges Montrose, would secure a hit single) through to the effervescent Ain’t Talkin’ ’Bout Love – a song Eddie wrote as a joke to take the piss out of punk rock – the irresistible, harmony-drenched I’m The One and Feel Your Love Tonight, and on to DLR’s long-time party piece, bluesman John Brim’s raunchy Ice Cream Man, and aptly titled rocker On Fire, the album is the purest distillation of hedonistic, liberated, sun-kissed Californian rock music ever committed to tape. It’s fast cars, endless nights and loose morals, cheerleaders and cocaine, bongs and bikini tops, pure, joyous youthful rebellion, with every trace of self-doubt and self-restraint eradicated.

Just as The Beach Boys supplied the soundtrack to American adolescence in the 1960s, and the Eagles owned the 70s, with their stunning debut Van Halen boldly declared that the 80s would be their playground. And if David Lee Roth sold a new generation a brand new American dream, it was Eddie Van Halen’s jaw-dropping virtuosity that made the album truly sing, his sweet, outrageously playful, seemingly effortless and utterly electrifying playing lighting up the sky. From the moment the needle dropped upon the Van Halen album on stereos worldwide, every bedroom guitarist had a new gold standard to aspire to.

“Edward has a sense of adventure,” David Lee Roth declared, neatly encapsulating the guitarist’s mindset. “He will dive headfirst. We’ll see if there’s water in the pool later.”

“I can remember the specific place where I first heard Eddie Van Halen,” said Guns N’ Roses guitarist Slash in 2010. “I was at this elementary school that we used to break into after school was over, and we used to skate and race bikes in there. [Future GN’R drummer] Steve Adler, who had just become my best friend around that time said, ‘Hey, check this out…’ and he had one of these little Panasonic cassette players and he played me Eruption into You Really Got Me, and it was just like… Wow. Besides the guitar pyrotechnics, the overall vibe of Van Halen was very energetic, and very new-sounding, very fresh-sounding. It had a ton of attitude, it was just in-your-face.

“As soon as that record came out… it was 1978 so I was 13, and I hadn’t picked up the guitar yet… that signalled the end of rock as we knew it. Everything that had happened up to that point all sorta changed.”

“Mark my words,” wrote Rolling Stone magazine’s Charles M Young in his review of the album, “in three years, Van Halen is going to be fat and self-indulgent and disgusting, and they’ll follow Deep Purple and Led Zeppelin right into the toilet. In the meantime, they are likely to be a big deal… Edward Van Halen has mastered the art of lead/rhythm guitar in the tradition of Jimmy Page and Joe Walsh; several riffs on this record beat anything Aerosmith has come up with in years.”

When the album came out, the quartet hit the ground running, mixing headline dates in Japan and continental Europe with support shows and festival appearances. When they rejoined Sabbath’s Never Say Die! tour in America, the promoters should really have hired a crime scene investigator to draw chalk outlines around Ozzy, Tony, Geezer and Bill onstage every night – Sabbath were being absolutely murdered.

Back in Los Angeles in the first week of December ’78, their first world tour completed, the band received an invitation to a party from their record label. Warners wanted to present the quartet with platinum discs, as their debut album had now racked up sales of two million copies in the US alone. Held at the Body Shop on Sunset Boulevard, LA’s only all-nude strip joint, the shindig was a suitably raucous affair. The next day, however, Van Halen were back in Sunset Sound with Ted Templeman, working on album number two.

With each successive release – Van Halen II (1979), Women And Children First (1980), Fair Warning (1981), Diver Down (1982) - Van Halen grew in confidence and stature, assuming the mantle of America’s Greatest Guitar Band. In 1983, the quartet entered the Guinness Book Of Records after securing the highest-ever fee for a single performance, when Apple Computers co-founder Steve Wozniak paid them $1.5 million to headline the ‘Heavy Metal Day’ of the 1983 US festival above Ozzy, Judas Priest, Scorpions and Mötley Crüe.

“It was the day new wave died,” said Crüe frontman Vince Neil, “and rock’n’roll took over.” Though Eddie somewhat dismissed the idea of Van Halen being labelled a heavy metal band – “to me, heavy metal is just rock’n’roll. It’s a feeling put out at a high volume” – his influence upon three subsequent generations of metal musicians is inarguable. In his free-flowing, uninhibited, boundary-flouting playing, other musicians heard the sound of liberation – and his influence would be heard in the playing of everyone from Dimebag Darrell to Killswitch Engage’s Adam D.

“He was to our generation what Hendrix was to his,” superfan Dimebag commented. “He plays Eruption and you go, ‘Shit, I never heard a guitar sound like that in my life!’”

“In the guitar hierarchy, where Jimi Hendrix is God, Eddie was Jesus Christ, the Second Coming,” says Zakk Wylde, who joined Eddie onstage at Dimebag’s funeral in 2004 to toast the former Pantera guitarist. “Ed broke through less than 10 years after Jimi passed, but he sounded like the new age. It was like he came from another planet.”

With Van Halen’s profile raised immeasurably by the national television coverage given to their appearance at the US festival, the quartet’s 1984 album yielded their first US No.1 single, Jump, and took up a five-week residency at No.2 on the Billboard charts; it would go on to become Van Halen’s second 10 million-selling album. Ironically, the album that kept it from the top spot was Michael Jackson’s Thriller, which featured the on-loan guitar skills of a certain moonlighting Dutch-born guitarist on hit single Beat It.

Even the wildest parties must one day wind down, and the first cracks in the VH world came with the exit of David Lee Roth in 1985. Emboldened by the success of his debut solo EP, Crazy From The Heat, David branded the guitarist a “dictator” as he departed. “Nobody cares about Van Halen without David Lee Roth,” he sneered.

Labelling David a “clown”, Eddie Van Halen responded in the most cutting terms. “The problem with Roth was that he forgot who wrote the songs,” he told writer and long-time friend Steven Rosen. “I wrote them. And the songs are the heart of our music. I never listened to his words. I couldn’t have cared less what he was singing about.”

Van Halen promptly recruited former Montrose vocalist Sammy Hagar to front the band, and the new-look quartet scored Van Halen’s first American No.1 album with 1986’s 5150. Three consecutive Billboard chart-topping albums followed, each a little more sophisticated and mature than its predecessors, though Eddie’s playing remained joyously unrestrained. Sammy departed in acrimonious circumstances following 1995’s Balance album – “Balance was like pulling teeth,” he told this writer. “Things had got very dysfunctional by then” – but Eddie forged on, recruiting Extreme vocalist Gary Cherone for the confusingly-titled III album. Though the album received the worst reviews of his band’s career - “The fundamental problem with this album is the songs,” one UK rock magazine declared. “They’re shit” – the guitarist never lost his passion for the music… or the attendant lifestyle. In Japan to promote Black Label Society’s Sonic Brew album, Zakk Wylde caught up with Eddie in Tokyo, where Van Halen were booked to play three nights at the historic Budokan venue, and ended up partying with his hero into the wee hours.

“Van Halen opened up with Unchained and Ed was just killing it,” Zakk recalls. “He came up to my hotel room afterwards and he was playing my Les Paul, with the bullseye, and the guitar was hanging around his knees like Jimmy Page in 1975. He was playing every Led Zeppelin lick that he knew, from back when Van Halen played covers. It was insane, I had Jesus Christ in my room playing Jimmy Page licks on my guitar. Quite a night.”

That childlike sense of wonder intrinsic in Eddie’s playing from his very first time seeing Jimmy Page onstage never seemed to fade.

“All we’re trying to do is put some excitement back into rock’n’roll,” he told Steven Rosen as his band’s 1978 debut was racked in record stores worldwide. “It seems like a lot of people are old enough to be our daddies and they sound like it, or they act like it. It seems like they forgot what rock’n’roll is all about.”

Eddie Van Halen’s passing on October 6, after a long battle with cancer, hit the rock community hard, and tributes poured in from friends and fans alike. On Instagram, Slash posted a single black and white image of Eddie Van Halen with his self-made ‘Frankenstrat’ guitar and wrote ‘RIP #EddieVanHalen’. Tool’s Adam Jones posted three broken heart emojis. Machine Head mainman Robb Flynn called Eddie “the G.O.A.T. [Greatest Of All Time]”, adding: “My mind is seriously blown right now. I cried. He was one in a billion.”

Having battled cancer himself in recent years, Tony Iommi’s tribute to his old pal carried an added level of poignancy.

“I’m just devastated to hear the news of the passing of my dear friend Eddie Van Halen,” Iommi wrote. “He fought a long and hard battle with his cancer right to the very end. Eddie was one of a very special kind of person, a really great friend. Rest In Peace my dear friend till we meet again.”

In one of his last major interviews, with Music Radar, Van Halen was asked if he had any advice for aspiring guitar players. His answer was wonderfully simple.

“Bottom line is, you’ve gotta love what you’re doing,” he replied. “There are no rules. You have 12 fucking notes… do whatever you want with them.”

“Eddie reminded us that music is freedom,” says Halestorm’s Lzzy Hale. “He inspired all of us to be unapologetically ourselves when it comes to technique or how we see the guitar. Rock stars don’t fade, their magic is passed down and lives forever through all of us. I believe that not just this generation, but many generations to come will be influenced in some way by Eddie’s legacy.”