As a teenager hooked on The Beatles, Jeff Lynne dreamed about being a pop star. As the sound of the Fab Four’s Please Please Me filled the modest family home in Birmingham, he imagined an alternative universe of girls, glamour, fame and fortune.

Instead, in spring 1972, Lynne found himself on stage with Electric Light Orchestra in a Liverpool club, surreptitiously urinating into a bucket. It was a milestone moment for the future Mr Blue Sky.

Prior to the show, he had visited an Indian restaurant and gorged on curry and lager. Later, several songs into the set, Lynne feared his bladder would burst and dashed into the wings, where his trusty roadie Phil held a cleaner’s bucket. Hidden by a stage curtain, Lynne continued to play guitar one-handed (“It was an open-string A”) while filling the pail.

As ELO’s cellists scraped away towards the song’s big finale, Lynne realised he was still some way from finishing. When he tried to hurry, he missed the bucket and soaked Phil’s arm.

With a barrage of expletives ringing in his ears, a urine-stained Jeff Lynne staggered back to rejoin his bandmates in time for the audience’s muted applause. Things could only get better

They did. In September 1974, John Lennon declared ELO natural heirs to the Fab Four. Two years later, A New World Record delivered their first Top 10 album in the UK and the US. Electric Light Orchestra saw out the 70s as multi-platinum pop stars, feted by film star Tony Curtis and victory-lapping the globe with a stage set shaped like a flying saucer. It was a long way from half-empty club gigs and pissing in a bucket. But Jeff Lynne was always an unlikely pop star. His daydreams came true: there were girls, glamour, fame and fortune: “But for me it was always about the studio and the music.”

ELO’s journey to world supremacy came via three albums – Eldorado, Face The Music and A New World Record – that forged Jeff Lynne’s reputation as a studio magus and musical perfectionist. But clues were there even in childhood.

Lynne grew up in the 1950s in Shard End, a post-war council estate near Solihull in the West Midlands. After attending his first gig, by Del Shannon of Runaway fame, Lynne complained that Shannon’s drummer didn’t sound like he did on the record. Before long he was dissecting hits by Roy Orbison and The Beatles to find out what made them tick: “It’s the way they built ’em that intrigues me.”

Lynne left school at 15 and joined a local band, who turned pro and later called themselves The Idle Race. But ELO grew out of The Move, the Brummie psychedelic group whose run of hits peaked with 1967’s Flowers In The Rain. “By the time I joined The Move [in February 1970] they were moving into cabaret,” said Lynne, “and I didn’t want to do that.”

Roy Wood and Bev Bevan, The Move’s frontman and drummer, shared Lynne’s misgivings, and ELO was born. Described in New Musical Express, as “a 10-piece mini orchestra”, their self-titled debut album was trailed by a UK hit, 10538 Overture. An unimpressed Lynne later called the LP “a self-indulgent non-event”.

Roy Wood told the press ELO would carry on where The Beatles’ I Am The Walrus left off: dressing Sgt. Pepper-style pop with classical trimmings. But Wood walked out during the recording of 1972’s ELO 2 and formed Wizzard instead. “We couldn’t work together,” said Lynne. “It was like having two bosses.”

From now on there would only be one boss. ELO 2 impressed America with its string-driven version of Chuck Berry’s Roll Over Beethoven. But even allowing for a pre-gig overload of lager, early ELO gigs were chaotic affairs, with the sound of the cellos clashing with the guitar and drums. “There were about four years of whistling, belching and groaning sounds,” recalled Bev Bevan.

Musicians came and went as Lynne struggled to recreate the sounds he heard in his head. He came his closest yet in summer 1973 with Showdown, a sad, sonorous pop song with swooping strings and a riff nicked from Marvin Gaye’s I Heard It Through The Grapevine. Showdown was a minor hit. But John Lennon was so impressed he anointed ELO “son of Beatles” in an interview with a New York radio DJ. Lynne felt empowered. But his father, plain-speaking Philip Lynne, who spent his working life paving roads for Birmingham City Council, thought otherwise: “My dad said: ‘The trouble with your tunes, son, is they’ve got no tunes.’ I thought: ‘I’ll show ya.’”

Enter ELO’s fourth album, Eldorado, and its big ‘tune with a tune’, Can’t Get It Out Of My Head. But it didn’t come easily. Lynne devised the story of Eldorado about a young man who escapes his dull everyday life by escaping into a fantasy dream world. Here, in his alternative universe, he hangs out with Robin Hood, fights medieval battles and becomes irresistible to women.

Work on the album began at North London’s De Lane Lea Studios in February ’74. To realise his musical dreams, Lynne hired a 30-piece orchestra to be conducted by ELO’s new young arranger, Louis Clark. “It was Clark’s first London session and because he was a new face they gave him a particularly hard time,” recalled studio engineer Dick Plant in 2011. “They were larking about and taking the mickey.”

During Eldorado Finale and Nobody’s Child (Lynne: “About a young lad being seduced by an older woman”) some of the orchestra musicians were so annoyed the session had overrun, they noisily packed away their instruments while the band were still playing. Lynne lost his temper and sent them all home. “Jeff was incensed,” recalled Plant. “But I got the impression he was already hatching a plan.”

ELO’s manager was Don Arden, the impresario who’d guided the Small Faces in the 60s and whose reputation for intimidation and violence preceded him. Nobody knows if it was Arden or Lynne who made the call to the Musicians Union. But two days later, ELO and the orchestra were back at De Lane Lea with Don Smith, head of the Musicians Union, in tow. Lynne made Smith wait 20 minutes before rounding on him in front of the orchestra, telling him the session had overrun because his members were unco-operative and incompetent. The outburst left the imposing Smith (nicknamed Dr Death by some union members) shaken. Smith ordered the musicians to carry on playing and told Lynne the MU would pay for the extra session.

Years later, Lynne played down the problems when discussing Eldorado Finale. “I like the slightly daft ending, where you hear the double bass players packing up their basses, because they wouldn’t play another millisecond past the allotted moment,” he joked. But the studio was Jeff Lynne’s fantasy dream world, and God help anyone who interfered.

Eldorado’s sleeve image was inspired by another dream world: The Wizard Of Oz. Not that Lynne realised. Don Arden’s daughter, the future Sharon Osbourne, was now working for her old man and had to explain that the ruby slippers and green hands were from one of the most iconic movies of all time. Lynne hated the image, but in the end he didn’t really care; the music was all that mattered.

Too late. Eldorado’s brand of what the press called “rock’n’roll chamber music” cracked the US Top 20 with Can’t Get It Out Of My Head, giving ELO their first US Top 10 hit. But Britain still wasn’t listening. “We might sell out in Birmingham one night and do nothing in Grimsby the next,” moaned Lynne in an interview with Sounds. “Why should we play here when we can earn fortunes in America?”

Before long, ELO were opening for UFO and Deep Purple in US ice-hockey stadiums. America was now their Promised Land. But there was more to it than sales. Forget The Wizard Of Oz, Lynne had grown up on American TV cop shows. Cruising down a palm-tree-lined Sunset Boulevard, squinting in the LA sunshine, “reminded me of 77 Sunset Strip and Dragnet and all these fabulous old detective shows”, he explained.

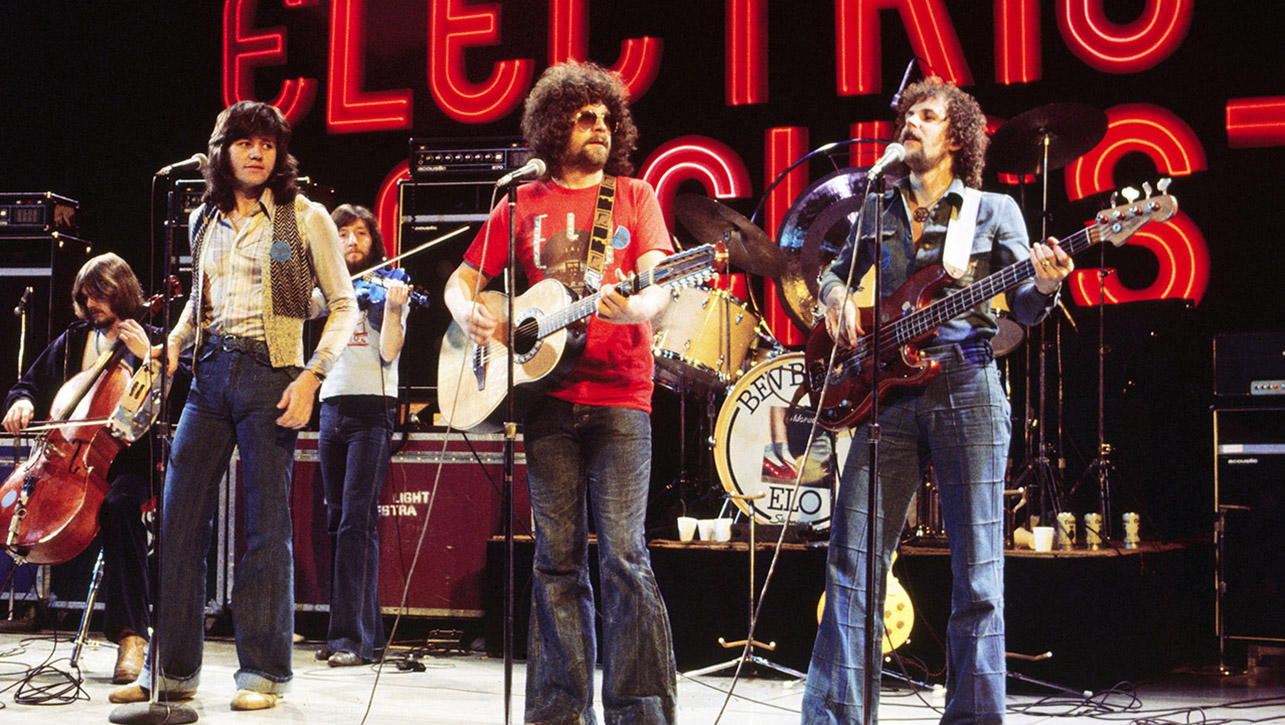

The ELO line-up had now settled around Lynne, Bevan and pianist Richard Tandy, cellists Mike Edwards and Hugh McDowell and violinist Mik Kaminski. The newest member was Kelly Groucutt, he of the Brillo pad hair and moustache, who’d replaced original bass player Mike de Albuquerque.

From now on, ELO would spend a ridiculous amount of time on the road, doing the things bands did on the road. “There was such a thing as an ELO groupie,” said Lynne, although ELO only trashed a hotel room once – in Washington DC, the night before visiting the White House: “And we felt terrible about it afterwards.”

“Touring with ELO was like running an old-age pensioners’ club,” complained Sharon Osbourne, who accompanied them on several jaunts. “All they wanted to do was sit in their rooms doing their knitting. I was so bored I would drink to amuse myself.”

When American Express called Don Arden to question a £150,000 spending spree on clothes, booze and jewellery, Don thought ELO had run riot with the company credit card, but it was Sharon.

The closest ELO came to excess was on stage when Hugh McDowell threw his cello in the air and Mike Edwards blew his up. Desperate to appear more exciting, the string section devised several visual gags. Edwards’s first party piece involved miming playing The Dying Swan while rolling an orange down the neck of his cello. From there, he graduated to explosives.

I didn’t really fancy it, but they had this thing built,” Edwards told an ELO fansite. “Hugh would be playing this piece and I would be miming to it on this cello.”

At a key moment, he pressed a button with his foot and the cello fell apart in a puff of smoke, leaving him ‘playing’ a mess of wood and strings: “Then we’d put it back together for the next day.”

It was all a bit much for Edwards, who left soon after, became a yogi master. Later he died when the van he was driving was struck by a 590-kilo hay bale. His replacement was young session ace Melvyn Gale, who inherited his predecessor’s exploding cello and detonator. Gale played a whole American tour believing he was a hired hand before being told at Heathrow Airport he was actually in ELO and they were going to Europe next. “I honestly had no idea,” he said. “I thought I was just booked to do that tour. But they said: ‘No, you’re in the band, and what we’re doing, you’re doing.”

Communication was never Jeff Lynne’s strong suit. The sunglasses without which he was rarely pictured were, as Sharon Osbourne put it, “Jeff’s shield against the world”.

Come February 1975, ELO’s lowly status in Europe was apparent when they toured Germany with support act Barclay James Harvest, who sold more records there than ELO did; a fact driven home by how many people left before ELO came on.

In August ’75 they landed a UK Top 5 hit – sort of – with somebody else’s song. Lynne, Bevan and Tandy played on the novelty single *Funky Moped *by Bevan’s old school friend, comedian Jasper Carrot. Once again, things could only get better.

They did. ELO ditched Britain and went to Munich’s Musicland Studios to make their next album, Face The Music. Like Melvyn Gale, studio engineer Reinhold Mack soon discovered that Jeff Lynne wasn’t a great talker. “Every morning, his attitude would be cold, as if I’d never met him before – walking straight past me without even saying hello,” he recalled.

Lynne’s inability to express himself manifested itself in the studio. His favourite question to Mack was: “Can you make it sound more weird?” without explaining what ‘weird’ was. Lynne’s approach to recording was to ‘carry’ the song around in his head and build it in the studio, while keeping everyone in the dark about details such as the melody, chorus or lyrics.

“I had the tune in my head, but I never told anybody what it was,” he admitted. “It was always a mystery to everybody. I’d have ten tracks full of orchestra, choir, group, everything – a great big sound and no words.” His collaborators struggled to make sense of it all, but the boss was in his element.

On Face The Music, Lynne finessed ELO’s usual hybrid of fiddly prog-rock and pop. Songs such as Strange Magic and Evil Woman suggested less of the former and more of the latter. Released in autumn 1975, Face The Music was another US hit, but missed the British chart. But there was hope in sight when Evil Woman finally gave ELO that precious UK Top 10 hit.

Here was a song that used everything Jeff Lynne learned from dissecting other people’s records, but given the ELO spin. Evil Woman’s piano intro briefly echoed Fats Domino’s B_lueberry Hill_; the strings could have come off a Philly soul hit; the line ‘There’s a hole in my head where the rain comes in’ was a tribute to The Beatles’ Fixin’ A Hole; and there was even a hint of disco in the rhythm. Evil Woman was a perfect pop record. “And the fastest song I ever wrote,” said Lynne, who composed it in just six minutes.

ELO celebrated the only way they knew how – with another gruelling American tour, playing 65 shows in 76 days. Don Arden had listened to Sharon’s criticism and accepted that ELO – ostensibly seven blokes with long hair and varying degrees of facial hair – were not showmen. Arden shelled out for some lasers to dazzle the audience in the downtime between McDowell flinging his cello in the air and Gale blowing his up. “The lasers were there to compensate for us,” admitted Lynne.

ELO were selling records and filling venues, but there was a down side. “Touring played havoc with relationships and anything like that,” said their leader. Lynne’s schoolteacher wife, Rosemary, agreed. Soon after, he left her for a new American girlfriend, future second wife Sandi.

When ELO returned to Musicland studios in July 1976 to make A New World Record, Lynne surprised everyone by bringing in some love songs. Mack, who’d engineer several ELO albums, maintained that Lynne’s love life was chronicled in some of ELO’s biggest hits, including Don’t Bring Me Down: “They were usually aimed at his [second] wife, Sandi.”

The pattern started on A New World Record, which contained several of what the group punningly called “bad salads” (sad ballads), including Above The Clouds and Telephone Line, the latter about the perils of a long-distance love affair. “Telephone Line was the saddest of them all,” said Lynne, who was inspired to write it after calling his American girlfriend and getting no reply. Lynne’s voice sounds truly desperate when he croaks the opening line, ‘Hello, how are you?’ This was the heartache of Roy Orbison’s Crying reconfigured for Top Of The Pops and Britain’s tank top-wearing, Chopper bike-riding youth.

But A New World Record (its title inspired by watching the Montreal Olympics on the studio telly) wasn’t all romantic disenchantment. There was also a sterling cover of The Move’s Do Ya and the exultant Livin’ Thing, with leather-clad pop star Suzi Quatro’s sister Patti on backing vocals. Both Livin’ Thing and Telephone Line would become Top 10 hits in Britain and America. A New World Record followed suit. Philip Lynne was forced to concede that his son was finally writing ‘tunes with tunes’.

Out on the road, ELO played beneath a giant black balloon with their logo on it. Meanwhile, Don Arden’s new lasers were so powerful when the band played Universal Amphitheatre in Los Angeles that they lit up the San Fernando valley and interfered with air traffic flying into LAX airport. ELO were bigger than ever; bigger than everyone. But the cracks were beginning to show.

“There were two separate camps,” said Lynne. “There was us – the rock’n’roll players – and then there were the string players.”

In reality there was Lynne and his trusty wingmen Bev Bevan and Richard Tandy in one camp and everybody else in another. Eventually there would just be Lynne in one camp and everybody else in another. But not just yet.

ELO started their touring life in 1972 playing shabby clubs where their cacophony of cellos and violins were either inaudible or unlistenable. By 1978 the group had notched up their biggest-selling album yet, Out Of The Blue, and further hits including Mr Blue Sky and Sweet Talkin’ Woman. They were now touring with a £100,000, spaceship-shaped stage set that looked like the UFO in Close Encounters Of The Third Kind and when it ‘took off’ sounded like a Boeing 747.

ELO’s eight-night run at London’s Wembley Arena in 1978 began with an introduction by Hollywood screen idol Tony Curtis, and ended with a backstage reception attended by the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester. Not that Jeff Lynne was impressed. “The spaceship was great,” he conceded, “but I’d had enough of touring by then.”

At the post-gig reception with its canapés, champagne and royal hangers-on, Lynne was more impressed by the gold discs lining the walls. “I kept thinking: ‘Those are for songs I’ve written.’ That was the problem – I just wanted to be in the studio.”

Lynne kept the ELO name alive until 1986, after which he went off to produce albums for celebrity pals including George Harrison and Tom Petty.

After years in the wilderness, Lynne revived the brand for a sold-out show in London’s Hyde Park in 2014. Although shielded from the world behind those omnipresent sunglasses, there were moments when the façade cracked and he looked genuinely touched by the audience’s reaction. He has since signed a deal with Columbia and a brand new ELO album will be out next month.

Of all the great soft rock bands, ELO never have had the gravitas of the Eagles or Fleetwood Mac. But they had the tunes. Lynne’s lonesome ballads and tales of ordinary folk escaping mundane lives seemed to come from the heart, even if he liked to pretend otherwise. As a teenager hooked on The Beatles, Jeff Lynne’s dreams came true. But, even now, the studio is the place where he’s happiest.

“When I’m there I block everything out,” he said. “I sit with the headphones on, thinking: Oh, this is the fucking life.’” Order in a curry and a pint, and you suspect Jeff Lynne would be in heaven.