Few bands are quite as adept at challenging genre definitions as Norway’s Enslaved.

Forged in the black metal cauldron of the early 90s, when core members guitarist Ivar Bjørnson and bassist/ vocalist Grutle Kjellson were a mere 13 and 17 years old respectively, they’ve long since journeyed beyond its philosophical and stylistic trappings while staying true to its original, innovative impulse. And although they were one of the first bands to use the term ‘Viking metal’, their ongoing fascination with Norse mythology refuses to look backwards, steering clear of anachronistic folk melodies and instead embarking on a journey of sublime, progressively tinged reveries and wayfaring, blade-sharp riffage.

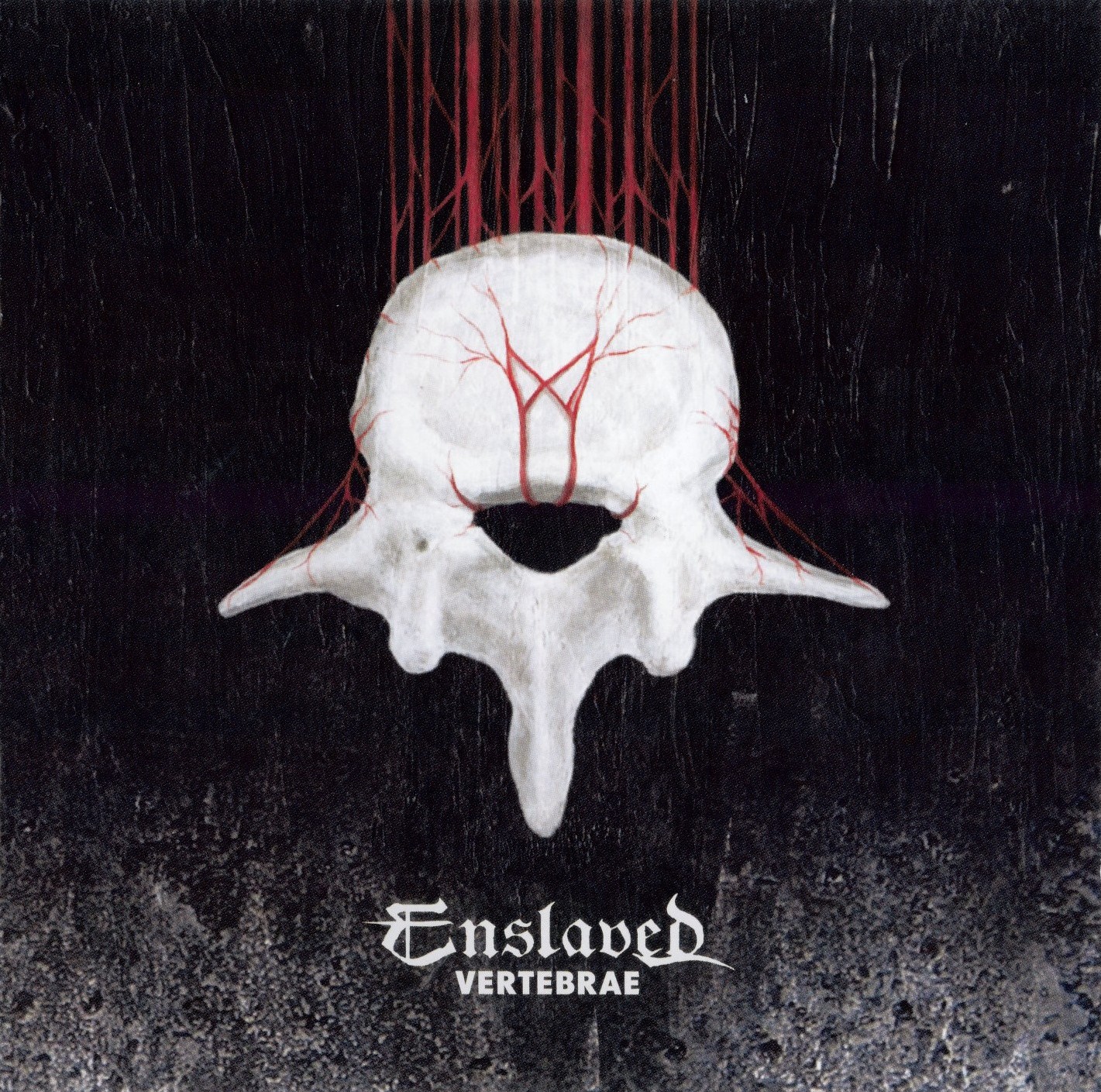

It’s an imaginative leap into the unknown that now garners the same kind of awe and anticipation in their fans as their equally intricate Nordic neighbours, Opeth. Enslaved’s breakthrough came with 2004’s Isa, an album that took the newfound potential seeping out of its predecessor, Below The Lights, and charged it with a scintillating grace whose fierce invocations and airy, opened-ended odysseys remains a redefining moment for what can still be done with extreme metal.Their latest,Vertebrae,takes that promise into more far-flung territories yet. An album that seems to be carried within a single, all-encompassing current from its first, billowing, frost-smitten note to the last, it travels though moments of vivid, heart-in-mouth surges, Sonic Youth-style, off-kilter eddies and rich, Pink Floyd-soaked textures that draw you helplessly into their slipstream while putting you into an unbounded, dream-like state for its duration.

“We’re doing this mainly to entertain and push ourselves,”says Grutle, seated in a Bergen café during unseasonably pleasant weather. “When we started to work on the new album we totally forgot everything we’d done before, because we want to make our favourite metal music at the time being. That’s what we’ve always been doing.”

“We get easily carried away with music,” adds Ivar. “Back in the day when we were making our first album, it came as a bit of a surprise to some people in the extreme metal scene that even during that time with the days of the black metal inner circle and all that, it was an incredibly open-minded scene at the same time, musically. It was very closed-minded ideologically, but there was so much emphasis on performance and pushing limits. You had to release the best demo ever, and at the same time, Euronymous [Mayhem founder and black metal linchpin, famously murdered by Varg Vikernes] would recommend everything from Tangerine Dream to The Residents and even Buddhist meditation music.”

Back in 1991, 1992,” Grutle recalls,“there was a fantastic creative metal scene in Norway. There was us, Emperor, Mayhem, Darkthrone and Immortal. All the bands sounded very different.”

It was that creativity, but also the strict codes of the early Norwegian black metal scene, that gave Enslaved the means to break free and find their own path.

“It was very easy for us,”says Ivar. “Back then, it was just Satanic lyrics = black metal. If that Satanism wasn’t in there, then it was either death metal or thrash metal, and more and more bands felt they were missing a genre. We used ‘Viking metal’ as a genre for a short period of time.”

“We should never have done that,”his bandmate grumbles.

Did ‘Viking metal’ become an albatross around their necks, particularly when other bands were using the term for completely different purposes?

“Not anymore,” states Ivar. “We’ve been telling people what we’re not for the past 16 years. For one period of time it was frustrating because it ended up like an argument. We’d say we weren’t black metal, and people would say,‘Yes,you are’.But now it’s more like it’s so vast and the whole thing has changed. Now if it’s got snarly vocals and heavy distorted guitars going fast it’s black metal, so it’s easier to understand why people want to categorise us as black metal, and now I feel that it’s moved away from the conceptual definitions.

“If people want to call us black metal, they do. If they want to call us Viking metal, they do. What we should have done is given Gene Simmons a call and asked how we could have copyrighted ‘Viking metal’. Then we wouldn’t have to play gigs anymore, we could just cash in…”

“To the Norwegian press we’re still black metal,” Grutle adds darkly. “We’re the most evil band on the planet in the local newspaper in Bergen.”He bats off the obvious question: “Let’s not talk about that, I might be getting sued…”

The terms Enslaved don’t have an argument with these days are prog and psychedelia. The increasingly expansive nature of their music, full of elegant complexity and passages of visionary languor all step back into the exploratory sounds of the 70s in order to find new ways to move forward.

“Black metal and psychedelia are very related, I think,” muses Ivar. “When Grutle and I started the band and got into death and black metal, he already had that knowledge of all that 70s stuff while I more or less came directly into metal. That was my first music thing. So during the late 90s we spent a lot of time discovering the old psychedelic bands like King Crimson and Pink Floyd and Hawkwind. There was a similarity between classic Darkthrone and the lengthy songs that would just keep going and going and going. There’s something almost metaphysical in it. I think it’s because it’s resembling meditation because it’s so repetitive, and the harsh noise sort of numbs your upper consciousness, and that’s why it starts to leak from your subconscious. That’s why we started listening to the influence of psychedelic music, seeing that it was putting across something very old and primeval, a ritualistic numbing.”

“Someone asked me recently ‘How would you describe your music?’” adds Grutle, “and I said, ‘Pink Floyd with a ton of bricks’.That was the only thing that came into my mind, but it’s fitting.”

Although Enslaved’s previous albums, such as 2006’s Ruun, have all been concept albums woven around Norse mythology and symbolism, Vertebrae might be their most potent yet. A subtle dig at extreme metal’s obsession with attacking abstract Christianity, the album is their attempt to find an answer to the very real, dangerous effects of religion worldwide in our current, turbulent times.

“The concepts have always had some linkage to the real world,” Ivar offers, “but this time I think it has even more relevance, and our whole internalising of mythology and metaphors has come to a point where we’re speaking more directly. Before it was more referencing, like hyperlinks, but now it’s more direct from us. If you want to simplify the lyrics, they have a lot to do with individualism, releasing potential and that’s a very global thing now, because at the heart of extreme metal has always been a hostility towards religion and political systems that oppress people and take away that possibility to develop and have your freedom.And while in the early 90s it seemed more like, ‘Why are they singing about this, it’s not a an actual problem’, today it is a very actual problem, and a very global one too.”

For Ivar and Grutle, there’s no contradiction involved in referencing ancient mythology while commenting on our current climate. For them,history isn’t just some former golden age to long for and a means of escapism, it’s an ever-present undercurrent to be delved into as guidance for the here and now.

“It’s about digging it up, definitely,” reckons Grutle. “Everything is written down by Christians because we didn’t write like them, and we didn’t pass on our mythology in that way. Everything was written down centuries later, and obviously you have to dig in and get into the core of the mythology, beyond the layers the Christians put on because they wanted to make it look a little bit ridiculous. They were interested in the poetry, but they didn’t like the mystical side. They turned them into bedtime stories because they didn’t want to have to think about what they initially meant. That’s the process, and it’s still going on–what do these stories mean, and how do we use them today?”

Perhaps it’s that search for enlightenment that takes Enslaved out of the insularity of so much black metal, and grants them such wide musical vistas to explore. At times, their music borders on – dare it be said – uplifting…?

“I was very surprised by that feeling,”Ivar admits,“not uplifting, perhaps, but there’s some brightness. For me it’s the same as listening to Mayhem or some old Metallica – to me it’s never been about happy or sad, it’s been about energy. Sometimes it’s dark and sometimes it’s bright, but it’s either energetic and meaningful, or uninteresting. All that ‘evil versus good’ in music, I think I missed out on that.”

This was first published in Metal Hammer issue 185.