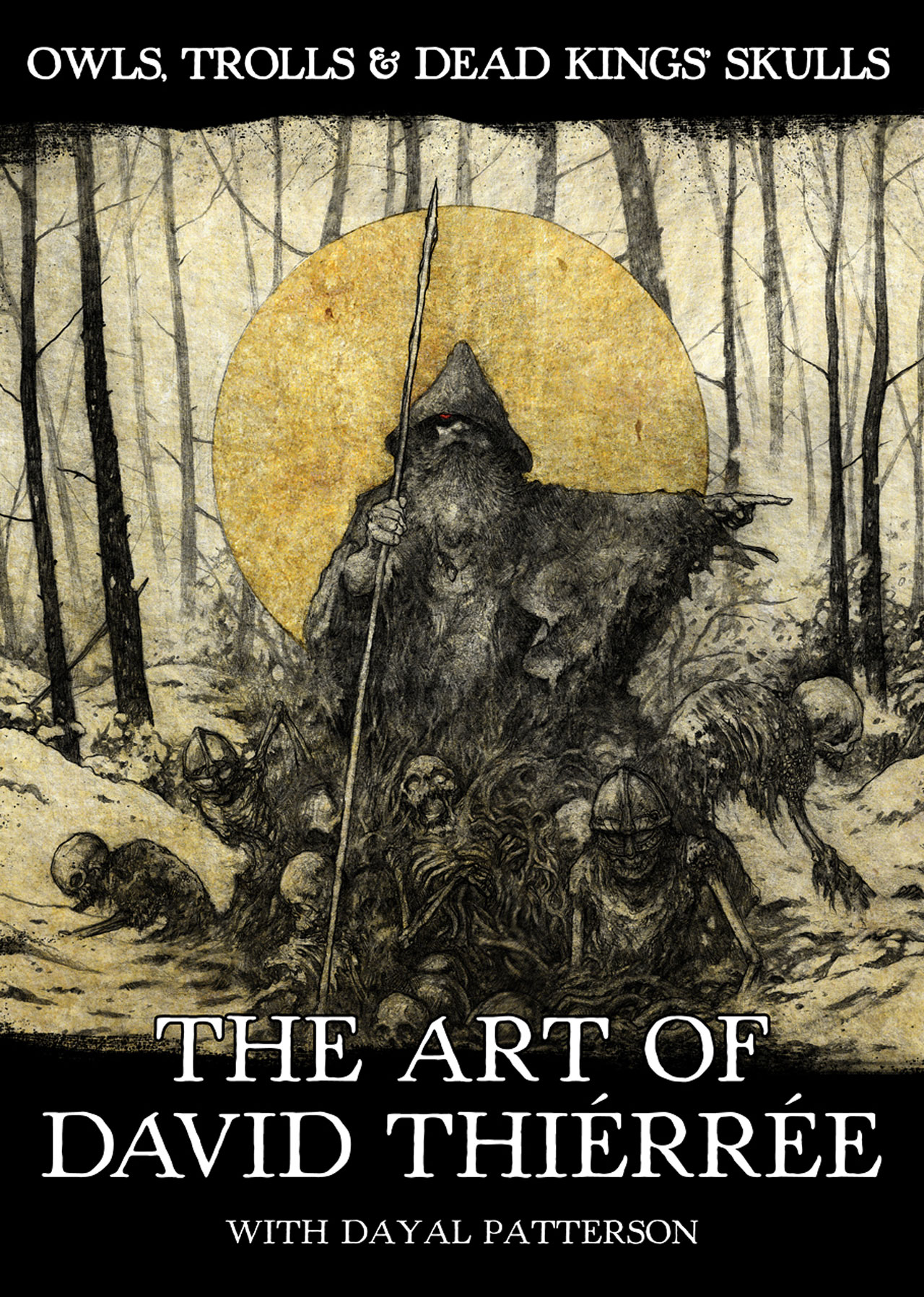

Released by Crypt Publications, the imprint started by Hammer scribe Dayal Patterson for his extensive Cult Never Dies series of black metal histories, Owls, Trolls & Dead King’s Skulls: The Art Of David Thiérrée is a stunning, 168-page large format tome dedicated to France’s renowned extreme metal and fantasy artist.

Featuring 200 prints, and featuring insightful perspectives from Nocturno Culto, Nergal and Mortiis, not to mention an extensive history of the artist himself, the book tracks the work of one of the metal scene’s most mesmerising talents, chronicling his journey through the black metal scene to the more fantasy-based style for which he’s become internationally renowned.

Below, we have an extensive interview with David himself, as well as more glimpses of his timeless and transporting art.

Were there any particular books or images that you came across during your childhood that set you on this path?

“Well, I think I had first been fed with imaginary worlds with comics (Marvel, DC, Conan comics, Italian and US horror comics, etc… as far as I remember, it was around 1977). Another step forward was back in 1979, when the Lord Of The Rings cartoon was made. After that came The Dark Crystal, Excalibur, Conan The Barbarian and so on. In the beginning of 1983, I bought my first role-playing books dice and catalogues from Citadel Miniatures. It all had very strong imagery with artists such as Ian Miller, Gary Chalk, Liz Danforth, Larry Elmore, John Blanche and Ian McCaig. Later, I began to collect books with more classic artists from The Golden Age Of Illustration: Rackham, Dulac, Goble, Booth, Beardsley, Robinson, Ford, the Pre-Raphaelites and symbolists.

“I was also really impressed by cover artists from bands like Yes, Jethro Tull, ELP, Iron Maiden, Kiss, later Venom, Bathory and Celtic Frost. So, it have been mostly popular culture from the 70s that drove me to fantasy and fantasy art, I barely remember Puss In Boots, Cinderella or Sleeping Beauty.”

How invested were you in the ethos of black metal? Was it more the imagery and folklore aspect that inspired you or was there a spiritual or anti-religious component too?

“A mix of them all, plus a strong part of love for this music. Black metal was really the epitome of the perfect link between what you feel inside and long for, and the sounds you hear. Besides the sheer brutality you need when you’re young, the pace and violence that you need to feed upon, black metal had also many mysterious aspects, driven by the covers, pictures in fanzines, flyers, logos, titles, everything. You could let your imagination fly and imagine dark creatures making unique music, challenging nature and elements during rituals in the wild.

“That’s where the Folklore parts comes in: this music evokes old ages, a kind of golden age that you feel you belong to more than the modern world. It drives quickly to this kind of self-confinement, where you try to survive the modern world that you want to let die by itself, and manage to make art for people who are a bit like you, and who you allow yourself to have social contact with. So black metal is all this, and I know a lot of people who went down the same path, and who are more or less like me now.”

What album cover provided the biggest challenge, and what did you learn from it?

“Things are smooth most of the time, sometimes bands pick up some drawing I made and choose it as their cover artwork. Sometimes, when I don’t feel I’ll provide the best artwork for the band, I prefer to redirect the band to another artist whom work will suits the band’s desires better.

“The biggest challenge is to come, I have to draw a dragon who rips the heart out of the chest of a lion, for a band from New Zealand. Wish me luck! But each time I have to provide unique artwork for a band is a big challenge, because I ask myself so many questions, about how to do it the right way. Sometimes, the band is a little picky and annoying, but it’s rare. There must be a part of the artist involved, a discussion about choices, and what may work or may not. This is a part of what is asked to the artist, his vision of what the band expect, but not simply executing what the band have in mind. There’s always something to change, because they simply can’t decide, because we can’t simply be in each other’s minds. Sometimes you have to let it go and let the artist bring his or her own vision.”

Were there any aspects of French folklore you were interested in exploring? Was your take on the Green Man in relation to its appearance in French mythology?

“Not too much, at least for the moment. I’ve illustrated a couple of them, for books or exhibitions, but there isn’t too much in French folklore that appeals to me, and those which I like, like The Wild Hunt, are mostly of Germanic origin. The Green Man is another example; it’s a fairly common archetype, but I prefer the way English people depict him. In France, the Green Man is reduced to medieval architecture embellishment. He is, in a way, dead. But in England he’s still alive, as a protector of many homes. He’s not a stone memory like in France, he’s depicted with vivid colours, and still dancing during festivals.”

What’s the particular resonance of trolls and owls for you? Do they represent aspects of the human psyche?

“Trolls and owls are, more than anything, things I like to draw – not only for aesthetic reasons, but also because I love to draw them. It may sound stupid, but it’s like when you like to manipulate some particular item, or taste your favourite meal. It ticks something in my brain to draw those particular shapes.

“I think owls, like cats, appeal to our need for protection, because of an eye/head proportions ratio, that reminds us human babies. And owls looks like a wise creature, keeper of the secrets of nature and are highly respected in the kingdom of the wild.

“Trolls are more emanations of the forces of nature, but not only that. For me, they’re emanations of everything that make people afraid: night, dark forests, crushing mountains under the moon, cold, freezing wind above the hills – everything that can make you feel like a vulnerable, lost, creature. They’re emanations of everything that you can’t control, and that can put an end to your life without even being conscious of it. This is what’s the Troll for me – not good nor evil, but a part of the wild around you. It doesn’t owe you anything, it doesn’t have to pay respect to you. You even don’t exist, he’s a part of nature, he is nature itself, as many other folks of the wilderness. You’re nothing, and that’s what frightening. That’s why humans are trying to control and destroy nature. They are afraid of it. So they don’t represent human psyche, they’re more how humans represent their fear of nature.”

What would you describe as the turning point in going more in a fantasy direction for your art?

“I began with fantasy art, and then was driven to music, so when I seriously slowed down my work for bands at the beginning of the 2000s, I went back automatically to fantasy drawing. I don’t remember a noticeable turning point. I think there have been something of a disinterest in the way the black metal scene evolved, a kind of boredom. As internet became more and more a way to communicate, all those ‘cyber’ concepts became all the rage everywhere, all those computer-made cover artworks. I also needed to focus on my family, as I’d just had my third child.

“I also thought that I needed to go further with my abilities, so I started to draw more intricate things, more female characters, and I tried to understand how woods, stones, etc, were made and how to draw them. I tried to understand more what symbolism was, and increased my ‘fantasy culture’, which once again drove me to the roots, and the Golden Age Of Illustration, and back to the 70s. The circle was somewhat complete, even if my early attempts were quite clumsy.

“This period helped me a lot to learn how to draw and compose bigger images, how to handle a pencil and paint, and I got a better all-round culture. I think that when I got back into the music business in 2008, I was fully ready, with a lot more to say than in 1994.”

Particularly in your later works, do you have a sense of an overall world in which they all belong to? Do you have any kind of backstory for the characters when you’re creating them?

“I link drawings in an unconscious way. Sometimes there’s a story behind some drawings (like the ‘Necropolis’ series), sometimes it’s more like being David Attenborough, during a trip, when you stop and stare at scenes, and eventually take pictures. You’re the David Attenborough of what lies inside my head. That’s more or less that. So I don’t feel the need to explain a lot what’s going on with this drawing or that painting, I prefer to let the viewer imagine everything, and what’s outside of the picture, just as I do myself when I look at artwork or listen to music I love.

“It’s even hard to find a title, that’s why most of the time my works are titled Trollskogen I, II, III, etc… One thing is for sure; they all belong to the same world, and are somewhat linked to each other. They’re all parts of my own private garden. If you look at my works, it’s a bit like watching a photo album of what’s inside my head. Sometimes I can tell you the whole story behind a picture, sometimes it will be harder.”

Would you say that there’s a higher function to art, be it in altering consciousness revealing deeply buried archetypes or something more?

“I don’t think so. There’s a part of the answer in the answer above. I don’t have a particular message to pass on. I draw to massage my brain by digging inside the drawing, adding more and more detail, to reveal paths and structures, characters and statues, skies and landscapes, and taking instant shots of a story witnessed ages ago. But nothing I feel like being in a particular state of consciousness or channelling anything.

“A friend said to me last week, ‘You must have a strong sense of belief to do this’. I answered him that I imagined that it existed, which is really different to ‘believing. Imagination is much stronger than belief, because it’s free. Once you truly ‘believe’ in faeries, gods, unicorn, or any bloody creature our human brains created during human history, you destroy something. It does not make faeries more beautiful or powerful to believe in them truly. They simply become another avatar of god, which is just once again, a way for your brain to avoid being destroyed by the consciousness of its own mortality. Being conscious of our own mortality is unbearable to humans, that’s why we create another world and life after death.

“So once you’re aware of that, you can imagine instead of believing. We’re only pieces of flesh on a small rock launched into the oblivion of space, we’re nothing. In my opinion, that makes all of this something more beautiful. It’s sad and desperate to create such things, to fly from our own consciousness, but it’s the tragedy of it, and it’s also the beauty of it. Romanticism is not flowers and courting, it’s the nostalgia for a lost golden age, or the spleen of worlds that never existed, except in one’s imagination. Imagination is everything, belief is vulgar and an insult to our mind’s abilities. And it kills people.”

If you could pick any band to work with, who would it be with, and why?

“There are many bands I would like to work with, for several reasons. Mainly because their music sounds like my drawings (at least in my opinion), like Darkthrone, Strid, Burzum, Arckanum, Urfaust, and of course early Ulver, Isengard, Troll, old Gehenna, old Ancient, Kvist, etc.

“There are bands that I would work for because I think the artwork they use isn’t the right one, in terms of accuracy or quality, but I won’t name any, because I try to be more polite and less rude. There are also some which I would like to work for, because I think my work would fit, like Mgła, Hate Forest, Borgne, Taake… too many bands to mention, in fact.”

Pre-order Owls, Trolls & Dead King’s Skulls: The Art Of David Thiérrée here

And check out David’s Facebook page here