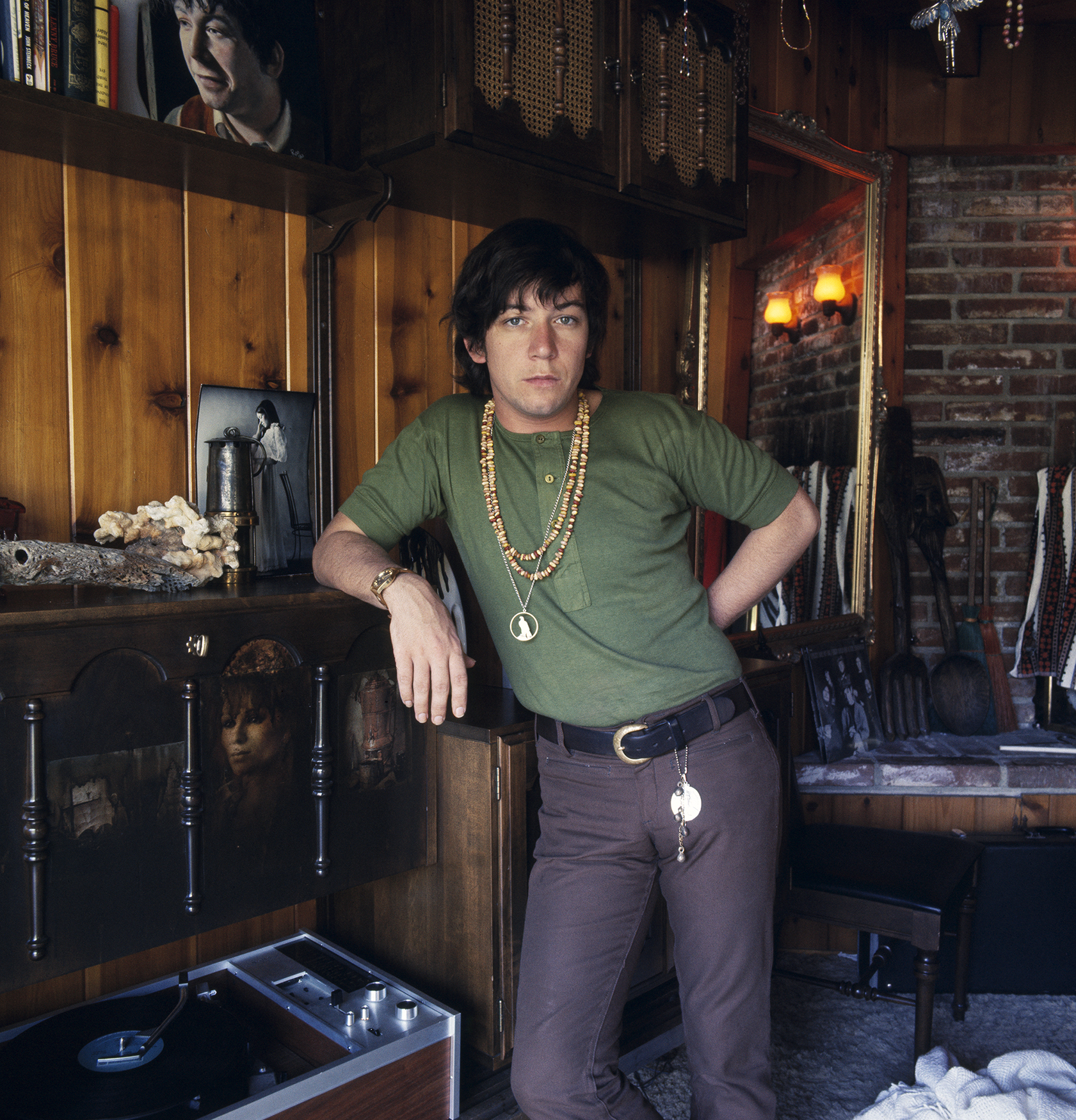

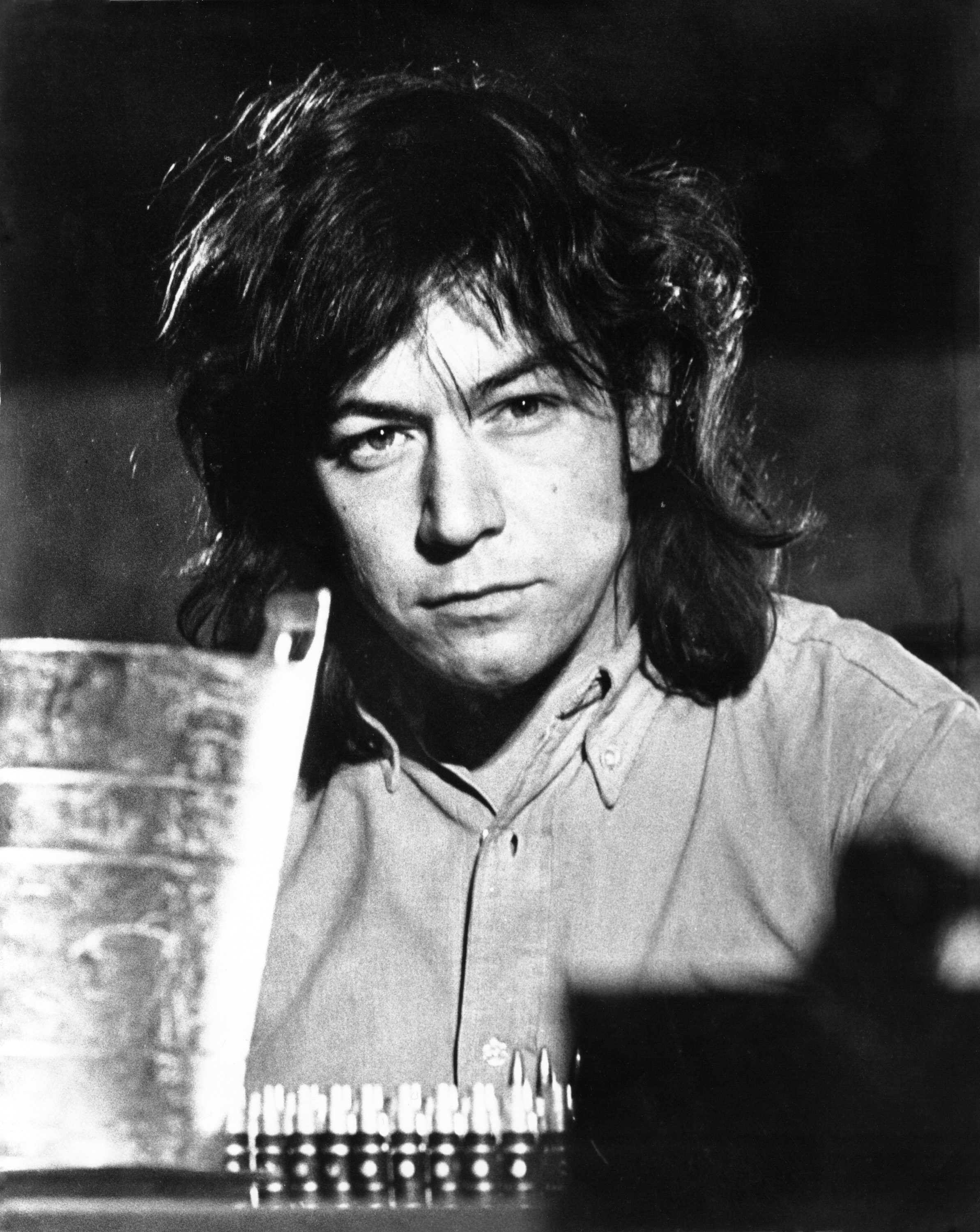

Eric Burdon: "The death of Hendrix was the end of the parade"

The legendary Animals and War frontman looks back at six decades on rock's frontline

It’s December 1963 in Newcastle. Sonny Boy Williamson, the Chicago blues harpist, is on stage at the Club A’Gogo, the city’s hip upstairs venue in Percy Street. He is backed by The Animals, a local five-piece formed just three months earlier. Their leader, singer Eric Burdon, duets with Williamson on a cover of Ray Charles’ 1958 single Talkin’ ’Bout You that has the audience clapping and rapturously singing along. It’s certainly not polished, but it’s loud and exciting, Burdon bellows with the fervour of a gospel preacher and the band pounds out the rhythm for Williamson.

The Animals, alongside The Beatles and the Stones, will go on to change the face of modern music, leading the Brit invasion of America with their new kind of R&B. In just over two years they’ll release nine singles and three albums in the UK and score a timeless number 1 with their revelatory cover of The House Of The Rising Sun that influenced Dylan into turning electric. “Sonny Boy reminded me of the early cartoon film character Uncle Remus [from Song Of The South]. He was a really nice guy,” Burdon, now 71, tells The Blues down the phone from Los Angeles.

Born on 11 May 1941 in the Walker area of Newcastle upon Tyne to his mother, Irene, and electrician father Matthew, Burdon’s musical education began when his parents gave him a portable Dansette record player. He remembers: “They bought some records for me to play until I could find what I really wanted.” One was Johnnie Ray’s Cry, an emotionally overwrought 1951 US Billboard chart-topper and a key influence on Burdon. “It was the first voice that made me realise you could sing differently, you could develop a style,” he says.

The next record to make its mark was Sixteen Tons by Tennessee Ernie Ford, a number 1 in the UK in January 1956. The tale of a miner who loads 16 tons of coal and finds himself “another day older and deeper in debt” chimed with working-class Newcastle, where coal was a core industry. “It was a working man’s hit,” Burdon concurs. “It was the song you would hear miners sing in the early hours of the morning on the smoke-laden double-decker buses on the way to work. They would be singing or humming a line from that song. It was like Walt Disney’s seven dwarves singing Heigh-Ho.”

Then, like most kids in the 1950s, Burdon became enamoured with the skiffle craze, where teenagers formed bands made up of guitar, tea chest bass and washboard for rudimentary percussion.

Lonnie Donegan led the charge, scoring a huge hit in 1955 with a cover of the Lead Belly song, Rock Island Line. Even back then Burdon was searching for the origins of the music he loved, noting, “You wanted to get to the depths of where skiffle came from and you realised that it came from the same source as the blues, the same area… in the [US] South.”

He also absorbed rock’n’roll, in particular black artists such as Fats Domino – “the real thing” – and Chuck Berry, who would become lifelong favourites. Burdon later covered both with The Animals.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The year after Donegan’s hit, the 15-year-old Burdon went to Newcastle College Of Art and Industrial Design where he met drummer and future Animal, John Steel. “We were compadres,” Burdon says, and it wasn’t long before the pair were playing college dances together with their band The Pagan Jazzmen. By early 1959 the band had evolved into The Pagans and featured Alan Price on piano, formerly guitarist with the Frank Hedley Trio. “We went to see them one day and during the interlude I heard him tinkling around on piano and I realised he was a better piano player than he was a guitar player. I said, ‘We’re putting a band together, do you want to play piano?’ He said, ‘yeah’.”

Then in 1960 the trio started a new band with a fluid line-up called “the Kansas City Five, Six or Seven, depending on how many people were in the band at the time.” Burdon remembers that, at one point, “We had two Africans in the band [Danny Okpoti on alto sax and Pat Odoi on trumpet] so early on we were aware of the black influence in music.”

They played any gigs they could get on the local jazz scene. Newcastle was “inundated with folk clubs and jazz clubs”, Burdon says. “I used to make myself such a nuisance that they would have to let me up on stage and sing a couple of songs. They realised that the audience liked it so it turned into a half-hour spot and that was when I first started singing.”

Hanging around in venues such as The Melbourne Street Jazz Club and The New Orleans Jazz Club, the young Burdon would check out the local talent and occasional out-of-town visitors such as Chris Barber and his band. Barber’s then wife Otillie Patterson sang with him and Burdon emphasises their importance in introducing him and his generation to the blues. Then, as visiting US blues artists started to play his hometown, the dedicated young blues convert would stand in a doorway at Newcastle City Hall watching for his idols to emerge. “If I waited there patiently enough I could get to meet everybody that I wanted to meet – Big Bill Broonzy, Muddy Waters – they all had to come through that door and I was there waiting to assist them. This was around 1958 or 1959.”

After a trip to London where Burdon sat in with Alexis Korner and Cyril Davis with Blues Incorporated, he was inspired to play with his own rhythm and blues group formed from various Tyneside bands. The five piece line-up solidified, with vocalist Burdon joining bassist Chas Chandler and keyboardist Price (who had both been playing with local pop group The Kon-tors), Steel on drums and Hilton Valentine from rock’n’roll band The Wildcats on guitar. Briefly known as The Alan Price Rhythm and Blues Combo, they soon became The Animals.

Between September and December 1963 the group made their name in Newcastle by repeatedly playing two hometown venues – The Downbeat Club and the Club A’Gogo, where they obtained a residency. Sometimes they would even play two or three sets on a Saturday night. Both clubs were owned and managed by Mike Jeffery, who would soon become The Animals’ manager. “The Club A’Gogo became a fixture of Tyneside’s music scene,” Burdon says. “We had The Yardbirds and Stones coming up to that club. We would switch gigs with them – go down south to play their gigs – and they would come up north to play ours.”

Visiting US bluesmen such as John Lee Hooker would play the Club A’Gogo and The Animals were recorded backing Sonny Boy Williamson there by visiting Yardbirds manager Georgio Gomelsky, though these recordings wouldn’t see commercial release until years later.

Burdon remembers, “I got the reputation somehow for being the guy that they would call on to be the chaperone for John Lee and Sonny Boy. It was a thrilling time for me to hang out with those guys and listen to their stories, especially Sonny Boy Williamson’s, he was one of the greatest story tellers ever. One day he was caught offering a young kid a glass of his whiskey (laughs) and Mike Jeffery said, ‘You can’t be doing that, you’ll go to jail.’ He said, ‘Sorry man I was just trying to be friendly.’ He was a real man child… No law at all in his life, just his law.”

During this period Burdon received an invitation that he couldn’t refuse from one of his heroes. “John Lee Hooker reached out to me in the form of giving me his address in Detroit. I [later] found him and stayed at his house for three days on The Animals’ American tour.” Jeffery, meanwhile, had funded the Animals’ first recordings on September 16, 1963 with engineer Phil Woods at the local Graphic Sound studio, the band covered Muddy Waters’ I Just Want To Make Love To You, John Lee Hooker’s Boom Boom, Jimmy Reed’s Big Boss Man and Bo Diddley’s Pretty Thing. These were issued as a limited pressing, one-sided 12-inch EP, sold in the Newcastle area to further promote the band. The wild, raw performances captured were far closer to how they sounded on stage than their subsequent hit singles.

A trip to London in December saw The Animals playing to enthusiastic mod audiences at venues such as The Scene club in Soho and, in January, the band moved to the capital. During that month they signed up with Don Arden for live gigs and independent producer Mickie Most to get them a record deal. The former put them on a tour supporting their hero Chuck Berry around the UK. Most recorded what he decided would be their first single, Baby Let Me Take You Home, an arrangement of folk song Baby Let Me Follow You Down, which Bob Dylan had recorded on his debut, and arranged a deal with EMI to release The Animals’ records on their Columbia label.

The energetic Baby Let Me Take You Home was a successful first step for the band, with a catchy guitar intro from Hilton Valentine leading into a record dominated by Alan Price’s Vox Continental organ and Burdon’s exuberant vocal. Its commercial mix of R&B and beat took it to number 21 on the UK chart and proved an old folk song could be adapted into a pop hit.

But it was The Animals’ second single, The House Of The Rising Sun, that made real waves, taking them to the top of the charts on both sides of the Atlantic and in Sweden, Finland and Canada in 1964. It made stars of them in the US, the home of the blues and rock’n’roll that they loved, and for a while they rivalled even The Beatles and The Rolling Stones in popularity. It would also plant the first seeds of the band’s demise when the arrangement was credited solely to organist Alan Price, who took all song writing royalties.

Burdon remembers the traditional folk song as a standard in many of Newcastle’s jazz and folk clubs.

“People loved the chord sequence so much they would play the opening chord opus and then they would sing one verse and that would be it.”

But it was the discovery of Bob Dylan’s aforesaid self-titled debut album in a local record shop that was to prove the catalyst for The Animals’ adoption of the folk song that had been recorded previously by Josh White and Lead Belly, among others.

“I played Bob’s version and realised that there were a whole bunch of lyrics to it that I didn’t know existed. We happened to be on the Chuck Berry tour and were looking for something that would make us stand out from the other support bands, who were in essence just trying to out-rock Chuck. I thought, let’s do House Of The Rising Sun, and it worked so well because people remembered it because it was different.”

Producer Most had the band record the song hastily in London during the tour, having driven down from Liverpool on a Sunday night. “We recorded it in one take and that was it – back on the road again with Chuck Berry. I think the recording costs were just the price of tape.”

The song’s success Stateside landed them a US tour which included dates at New York’s Paramount Theatre with Little Richard and Chuck Berry and a coveted appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show on October 18, 1964 where they played the song and also their follow up I’m Crying. “I remember every Ed Sullivan Show as being a complete disaster,” Burdon exclaims. “You had to sit through hours of jugglers flying around the stage to get to the one rock group that would be featured.”

Though their third single I’m Crying was a frantic piece of pop R&B written by Burdon and Price that reached the Top 10 in the UK, the band continued to rely primarily on outside songwriters. “We didn’t record more of our songs because Alan didn’t bother to sit down and work with me and then he left the band soon after that. I won’t mention anything else – it’s too painful,” says a rueful Burdon.

Before Price’s departure The Animals scored two more Top 10 hits, with covers of Nina Simone’s Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood and Sam Cooke’s Bring It On Home To Me and recorded two hit albums, The Animals and Animal Tracks. The former album opened with Burdon’s tribute to Ellas McDaniel. The Story Of Bo Diddley was an imagined account of the R&B star’s visit to the Club A’Gogo. “I always admired him because he had a great sense of humour, he was a very strong guy, he was very down to earth and, I think, very much underrated,” Burdon says. “He never visited the Club A’Gogo, but I never let the truth get in the way of a good story. We did invite him and his percussionist Jerome Green turned up. I just started thinking, well, what if Bo had turned up, and that was the beginning of the song.”

The latter album’s highlight is a version of Ray Charles’ I Believe To My Soul with an astonishing, heartfelt performance from Burdon. “For musical skill and essence of soul then Ray Charles took the biscuit,” says Burdon. “He was the man. Amazing!”

Price was replaced by Nottingham-born Dave Rowberry from The Mike Cotton Sound who debuted on We’ve Gotta Get Out Of This Place, which reached number 2 in July 1965. A gritty, working-class anthem in the hands of The Animals, with a magnificent, impassioned vocal from Burdon, it was written by Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, songwriters in New York’s Brill Building. “I had no idea what the Brill Building was,” Burdon says. “I just knew that there were writers out there that were submitting songs through our producer Mickie Most. Mickie’s real talent was not as a producer… back then his talent was finding material for the bands he was involved in.” He adds, “As soon as we heard We’ve Gotta Get Out Of This Place we thought it was written for us.”

Most provided another defiant anthem for the band with US songwriters’ Roger Atkins and Carl D’Errico’s It’s My Life, yet another Top 10 hit in October before they parted company with Most and EMI.

Signing to a new label Decca they released another single, Inside-Looking Out, and an excellent third album, Animalisms, but all was not well in The Animals’ camp. John Steel left during the making of the album and was replaced by Leicester-born Londoner Barry Jenkins from The Nashville Teens.

Burdon’s own favourite single with The Animals is their ninth, Don’t Bring Me Down, characterised by Dave Rowberry’s unusual organ sound, great fuzz guitar from Hilton Valentine and one of Eric’s most powerful and soulful vocals. “That was recorded in a hotel in the Bahamas which, again, was one of the first things The Animals could claim to be a part of, which was recording remote. We shipped equipment out from New York and recorded in a hotel room. The Holiday Inn, room 133 in the Bahamas. I remember there was an old record player in the room where we were recording and it had this strange, thin electrostatic speaker. Dave Rowberry connected it to his Hammond B3 and that’s where the sound comes from on that track.”

Another Brill Building song, Don’t Bring Me Down, hit number 6 in the summer of 1966, but Burdon felt it was time for a change: “I woke up one morning and realised that I was not with the Geordie band that had left Newcastle. We had lost our identity in adding new players. I’m not saying that they weren’t good players, it’s just that we had an identity when we left Newcastle – we were a Geordie band. All of a sudden, overnight it wasn’t the same thing.”

A final album from the band appeared in the US only, confusingly titled Animalism, and contained more Bahamas recordings and a couple of songs, All Night Long and The Other Side Of This Life, recorded in Los Angeles with Burdon’s soon to be pal Frank Zappa. “We were recording in the studio with Tom Wilson when he [Zappa] was doing the Freak Out album next door and he popped in to listen to us. He was friends with Tom Wilson and he just said to me, ‘I’ve got a couple of songs, do you want to try them out?’ and I said ‘yeah’. We got together after an Animals session and I recorded a couple of songs with him… My voice sounds ridiculously teenage, but it was fun. I got pretty close to Frank and later lived a few doors away from him in Laurel Canyon. I used to spend nights watching his 16mm experimental films which never came to light. I expected him to become one of the new world directors.”

One of Burdon’s proudest experiences was when Ebony magazine decided to do a feature on The Animals in the December 1966 issue, asking Eric to write “An ‘Animal’ Views America”, wherein he was pictured with John Lee Hooker and discussed race and music. “It was a big thing for me as Ebony was aimed at black folks and was their version of Life magazine,” Burdon says. “[They] wanted to do a photo spread on The Animals and how we were trying to align ourselves with black music. They found it interesting enough to do a magazine article. Linda Eastman, who became Linda McCartney, was our guide to New York and came along with us.”

Even before splitting the old Animals, Burdon had become an enthusiastic user of LSD but its use would be pivotal in shaping the music of his new psychedelic group, Eric Burdon & The Animals. He says, “I dropped acid man… mainly in LA but everywhere on the planet from then on. It was all over the place.” Burdon’s drug-taking wasn’t simple hedonism, he says. “We really did believe we could alter the world on a large scale, but of course all good things end up being bent out of shape and twisted and end up in the wrong hands with the wrong ideals.”

He was also besotted with the emerging counter culture: “I realised that there was a revolution going on in America, especially on the West Coast, so that’s where I headed for. Then on a visit back to London I ran into musicians who were like-minded and realised that there was this thing going on in San Francisco and we jetted over there and joined the revolution, which was a lot of fun.”

The British public were reluctant to accept Eric’s transformation from hard-drinking Geordie bluesman to LSD-endorsing, peace and love hippy. All four of their albums failed to chart. Most of their singles also sold disappointingly, causing Burdon to feel that England was no longer on his wavelength and from 1968 onwards he started to spend more time in America. The autobiographical debut single When I Was Young written by Burdon with the new band – Barry Jenkins (drums), John Weider (guitar/violin), Vic Briggs (guitar) and Danny McCulloch (bass) – was sonically adventurous, utilising an Eastern riff with Weider on electric violin as well as guitar while still retaining a bluesy feel. But it failed to make the UK Top 40. Burdon reflects, “We had several hit singles in the US which just didn’t go anywhere in the UK, so the message was clear.”

San Franciscan Nights – their one big hit in Burdon’s home country – told of his new enthusiasm for the West Coast underground culture. “I fell in love with California and the San Francisco scene, but I got a lot of flack from the people living in San Francisco saying, ‘Hey man, quit singing about our city, it’s been inundated with kids who’ve run away from home.’ That was the down side of it. To me it was the truth at the time.”

Eric Burdon & The Animals played at the Monterey International Pop Festival held in June 1967 alongside the cream of the music scene including Jefferson Airplane, The Who, Otis Redding and The Jimi Hendrix Experience (managed by Chas Chandler). Burdon appeared on the first night, unveiling San Franciscan Nights to a US audience for the first time. The new band were warmly received and their rendition of the Stones’ Paint It Black would appear in the D.A. Pennebaker film of the event. Burdon was so inspired that he wrote the song Monterey commemorating the festival. “The three days of Monterey were the three most perfect days in my life ever. I’ll never forget it. I can remember it like it was yesterday and I never went to another rock festival ever except the ones that I was performing at because I knew that Monterey was it, nothing would ever come up to Monterey.”

The song appeared on Eric Burdon & The Animals’ second and strongest album The Twain Shall Meet, alongside their musically ambitious, anti-war statement Sky Pilot, another single that sold in the US, but not the UK.

During 1968 Vic Briggs and Danny McCulloch left the group and keyboardist Zoot Money and guitarist Andy Summers, both formerly of The Big Roll Band and Dantalion’s Chariot, joined but the band would be over by the end of the year. One reason was that Burdon felt things had changed from the idyllic summer of 1967.

“It was pretty dark, you know. The dope gave you a brightness and lightness, but the flipside was a dark period and, in 1968, the whole thing exploded all over the planet – Prague, Paris, Los Angeles, London. The whole world was in turmoil by 1968, probably because of Vietnam.”

After the demise of Eric Burdon & The Animals, the disillusioned singer turned to acting. “I was tired of the music business and I went to the Actors Studio in Los Angeles for a year and thoroughly enjoyed that. It was great to be in a room of people who knew more than I did. I was really enjoying it and then I fell in with these street guys who told me, ‘What are you doing wasting your time? What’s this thing about wanting to be in the movies? You can’t do that unless you’ve got millions of dollars. The only way to get that is to go back to what you are good at and that is singing.’ They said, ‘We’re going to put a band together and how’s about being in front of a black band.’ I thought it was a great idea.”

That band was War, who formed in 1969 when Burdon and Danish harmonica player Lee Oskar joined members of The Nightshift, a Los Angeles club band that had been backing ex-LA Rams football star Deacon Jones. They quickly became famed for their explosive live performances, Burdon often improvising lyrics using both song and spoken word over irresistible grooves that mixed jazz, rock and funk. Two albums – Eric Burdon Declares War and the double set Black Man’s Burdon – followed in 1970 for the MGM label and that same year they scored a hit with the joyous, Latin-influenced Spill The Wine.

“We had two years of having a lot of fun and playing at great venues such as The Olympia in Paris. They loved us there, they loved us in Germany…We were the first non-jazz people to play Ronnie Scott’s. That had a big effect and we got great press.”

The death of his friend Jimi Hendrix on September 18, 1970, only two days after he had jammed with War on stage at Ronnie Scott’s, had a profound effect on Burdon. “That became the end of the parade because it affected us so much. It was tough for me, it was tough for everybody.”

Burdon remembers a previous visit from Hendrix that had forewarned him that all was not well with the guitar genius. “He came to Ronnie Scott’s club before that and I had to send him away because he was in such a bad state. You could almost smell the problems that he was having and, believe me, it was tough for me to say, ‘No, Jimi you can’t do it, come back when you’re in better form.’ He did, but it didn’t do much good. I was trying to reach him on many levels during that period… when I think about it now that’s what helped me get over my own 27th year, I was concentrating on other people like Jimi, who I could see was in deep trouble. He was very removed and in Britain he was a stranger in a strange land. The people who purported to be his friends were bringing him gifts of poison in the form of bad drugs that he was so ready to consume, he didn’t care.”

Burdon was dealt another blow when his colleagues in War made an album for a new record company, United Artists. “War went ahead and started recording without me and went across the street to a different record company and got themselves a nice juicy deal. I found out that I wasn’t a part of it. Things got really nasty from that point on.”

After splitting with War, Burdon’s next album was Guilty! in collaboration with blues legend Jimmy Witherspoon in 1971. The pair went on tour. “That was a great period of my life hanging out with Jimmy”, recalls Burdon. “He was always one of my heroes and we became close. He taught me a lot and I miss the guy. He was really a great person – tough but fair. We played San Quentin prison and there were moments that I was in heaven. There I was walking past Death Row with Jimmy Witherspoon, Muhammad Ali and his wife and Curtis Mayfield. I felt that I’d been propelled into the heart of black America. This was the ultimate experience of getting to see what it was like to be black in America and I could tell it wasn’t much fun, but they got on with their lives and I learned a lot. I’ll never forget it.”

Since then the original Animals have reunited twice, releasing comeback albums in 1977 and 1983, although neither outing recaptured the magic of the band’s 60s recordings and both were commercially disappointing. The Animals were then inducted into The Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame in 1994 although Burdon did not attend. He has continued to perform and record with various bands, and no matter who he is singing with or where, there is always one song his audiences expect to hear. “We were stuck with House Of The Rising Sun for the rest of our lives”, he says, “and I still am – and not earning a penny for it.”

After Bruce Springsteen called him up on stage for a cover of We’ve Gotta Get Out Of This Place at the SXSW Festival in 2012, Burdon was thrust back into the limelight and Springsteen credited The Animals as an inspiration. A deal with Abkco Records followed and his recent ’Til Your River Runs Dry is his strongest album since his days with War. With it Burdon has come full circle, with songs paying tribute to Bo Diddley and Fats Domino and a cover of Bo Diddley’s Before You Accuse Me. In addition the heartfelt, passionate idealist of the late 60s is reflected in Water, about water conservation and Invitation To The White House imagining what he would say if he met the President. His voice is still very much intact, and blues music is still very much at the centre of his sound. It’s an album he’s proud to have made, he has written ten of the twelve songs himself and feels his career is finally in good hands – his third wife and manager Marianna. Burdon reflects, “you’ve got to have good management. That’s what I learnt because I certainly didn’t have that for the first forty years.”

As our hour together comes to an end, he ponders for a second trying to sum up his previous 50 years of record-making. “I’d been screwed by [War], I’d been screwed by The Animals,” he says. “All use Burdon because he’s a great front guy and then come payday where’s the money? A lot of people had a great ride off me being on stage and I didn’t get much of it.”

He sounds sad, angry, maybe even bitter. Then Eric Burdon gives a little chuckle. “I’m not bitter,” he says. “I’m bittersweet.” And with that one of the greatest blues singers of all time is off.