It’s fair to say that Eric Clapton tends to polarise opinion. To the unknown graffiti artist who scrawled ‘Clapton is God’ on the wall of Islington tube station back in the mid-60s, and the fanatics who stormed the Royal Albert Hall for Cream’s 2005 reunion shows 37 years after their farewell ones, he is without question the greatest white blues guitarist of them all.

To Clapton detractors, on the other hand, whose number has grown steadily since his solo career got a little too comfortable in the 80s, he’s regarded as something closer to the Devil; the epitome of the bloated, Armani-clad superstar peddling mothballed hits to stadiums full of hedge fund managers.

Clapton sees himself in simpler terms, however. “I am, and always will be, a blues guitarist,” he once stated. And it was more than a neat soundbite.

Growing up as a “nasty kid” from a troubled home in 1950s Surrey, Clapton had found refuge in the music of blues heavyweights like Big Bill Broonzy, Blind Lemon Jefferson and BB King, studying their riffs on a tape recorder and attempting to finger them on a cheap acoustic guitar.

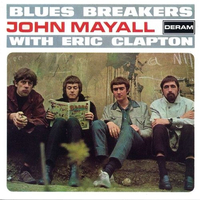

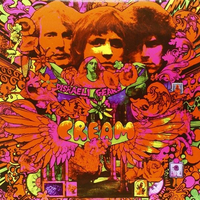

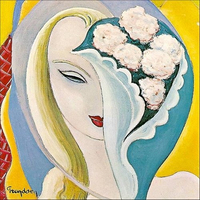

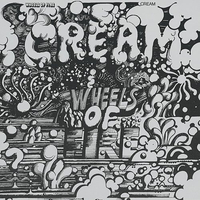

As his own technique blossomed, Clapton drifted out of art college and into the lineup of The Yardbirds in 1963, but quit two years later when he decided the band’s commercial ambition was compromising their blues roots. It was some measure of his commitment to the cause. What looked like career suicide ushered in Clapton’s most successful period, as he contributed searing guitar playing to John Mayall’s 1966 album Blues Breakers With Eric Clapton, then formed the power trio to end them all, Cream, with bassist Jack Bruce and drummer Ginger Baker. Over the next two years Cream’s three classic albums established Clapton on both sides of the Atlantic.

But by 1968 he was restless again. Feeling the band’s improvised live jams had grown stale, he handed in his meal ticket, passed through a handful of short-lived projects, and embarked on the solo career that continues to this day.

Ultimately, whether Clapton is a genius or an overrated relic depends entirely on the album you pull out of his back catalogue. Not even his most ardent admirer could deny that there have been missteps, runs of appalling albums and more than a little treading of water during his 42-year career. At the same time, not even his most vocal detractor could dispute that ‘God’, when at his best, comes close to a religious experience.

...and one to avoid

You can trust Louder Our experienced team has worked for some of the biggest brands in music. From testing headphones to reviewing albums, our experts aim to create reviews you can trust. Find out more about how we review.