After the visionary highs of the 1960s, Eric Clapton kicked off the 70s mired in a professional, personal and pharmaceutical nightmare. His semi-anonymous supergroup Derek And The Dominos had been largely ignored by the public – their signature song Layla, a thinly disguised wail of anguish inspired by Clapton’s unrequited love for model Pattie Boyd, wife of his friend George Harrison, had failed to chart. The guitarist’s woes were compounded when another friend, Jimi Hendrix, died in September 1970.

Mentally battered, Clapton and his socialite girlfriend Alice Ormsby-Gore gradually retreated from the limelight – and into a twilight world of heroin addiction from which he would not emerge until three years later.

Eric Clapton: With heroin, snorting it up the nose maybe three or four times a year was how I did it at first. Then I did it for maybe a week without stopping, and then two or three weeks not doing it. And then a month without stopping, and then come off and you’d feel bad. So to stop feeling bad you’d take some more, and then you’d be on it for six months.

Bobby Whitlock (keyboard player, Derek And The Dominos): Everything just got out of hand with the drugs and all that, so eventually everyone just drifted.

Eric Clapton: I don’t know whether it can be fairly placed at the door of drugs or relationships or life issues as much as I just had to get away. I had been doing so much; I’d been out there for a long time, playing and playing with no break.

Ronnie Wood (Rolling Stones guitarist and friend of Clapton): He withdrew with Alice Ormsby-Gore, and the two of them stayed stoned on heroin for two years. They became hermits.

Eric Clapton: Although we weren’t using any needles, we got very strung out.

Pete Townshend: He obviously had some cash-flow problem, because he was selling guitars… to raise ready cash to buy dope.

Eric Clapton: All that time, though, I was running a cassette machine and playing. I had that to hold on to. At the end of that period, I found I had boxes full of playing, as if there was something struggling to survive.

Clapton spent his time holed up in his Surrey mansion, Hurtwood Edge, with Ormsby-Gore. In August 1971, a concerned George Harrison convinced him to take part in the Concert For Bangladesh in New York, which he and Ravi Shankar had organised.

Pattie Boyd: Eric was in a bad way, but George thought that if he got him on stage, even propped up with drugs, his addiction would become an open secret and maybe he would open the door a little to his friends, who might be able to help.

Eric Clapton: I arranged by long-distance phone calls that there’d be something there for me because my heroin habit was going strong. So I fly over and there’s nothing there, and we can’t score.

Alice Ormsby-Gore: I was desperately running around that city trying to score some heroin for Eric. And I remember thinking how stupid it was for me, even then. I did that for him, and for myself, for three years. It was probably childish to be over-protective, but I thought it helped him not to have to face the full horror, himself, of scoring his own heroin supply.

Eric Clapton: Finally, one of the cameramen came up with this medicine that he took for his ulcers, which turned out to be a heroin substitute, methadone. It got me straight enough so that I could go on stage and play.

Ronnie Wood: He showed up, played, and after that, he and Alice just shut the door again and stayed smacked out.

Pete Townshend: Eric lost two people that he based his whole life on – Jimi Hendrix and Duane Allman – in fairly close succession. So there were a lot of reasons why he wasn’t working.

Ronnie Wood: His [Townshend’s] answer was to put together a concert, and then to convince Steve Winwood and me that it was time to drag Eric out of his reclusion in Surrey and up to London for rehearsals. Which is exactly what we did. We literally dragged Eric out of his house and moved him into mine.

Pete Townshend: The drugs were flowing very freely among the musicians, and I think Eric upped his intake of heroin – he stopped trying to substitute it with other things, which he had been doing to try to pull himself round. But his togetherness was a surprise. He was very, very strong, authoritative and confident.

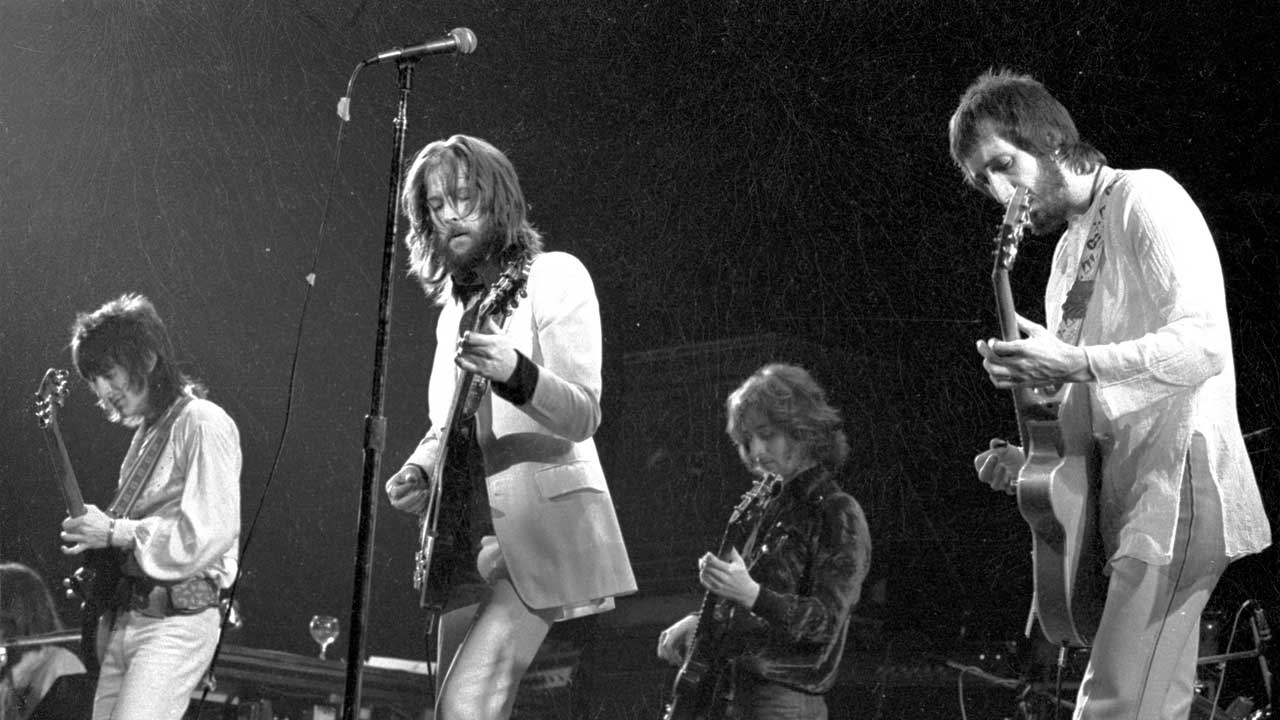

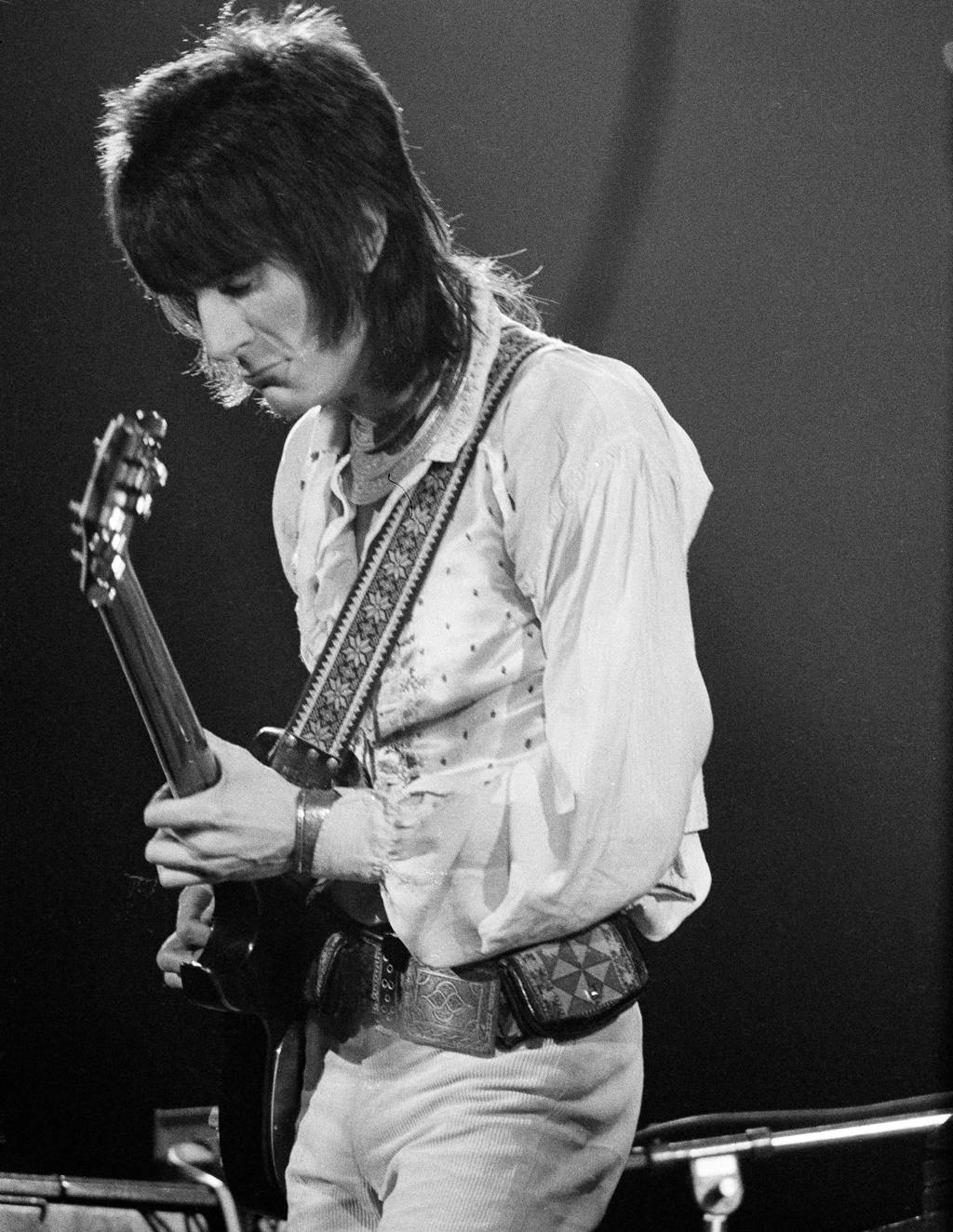

Following stage rehearsals at Guildford Civic Hall, Clapton’s comeback took place at the Rainbow in North London, where the guitarist played two sets on the same day, with a band that included Townshend, Winwood, Wood, bassist Ric Grech and drummer Jim Capaldi.

Eric Clapton: Alice and I, stoned out of our heads, turned up late [at the Rainbow], to find Pete and [Clapton’s manager Robert] Stigwood tearing their hair out. The reason for our lateness was that Alice had to let out the waist of the trousers of my white suit, because I had taken to eating so much chocolate of late that I couldn’t get them on.

Alice Ormsby-Gore: Five o’clock and there I am, sewing a six-inch piece of material in the back of the trousers with black cotton.

Pattie Boyd: I was sitting in the audience with George, Ringo, Elton John, Joe Cocker and Jimmy Page. Eric didn’t look well.

Eric Clapton: For the first few numbers I was in a daze. Then it suddenly clicked in and I began to get some confidence.

Ronnie Wood: We did the Hendrix hit Little Wing and lots of Eric’s big songs like Let It Rain, Badge, After Midnight and Bell Bottom Blues. By the time we reached the end of the set with Key To The Highway and Crossroads, no one had any doubts: Eric was back.

Jimmy Page: I saw him at his Rainbow concert. At least at the Rainbow he had some people with some balls with him. Pearly Queen was incredible.

John Pigeon (journalist, Let It Rock): Townshend was clearly taking his role as rhythm guitarist seriously, not just strumming along, but punctuating the music the way only he does. Ron Wood avoided the temptation to imitate Duane Allman’s part on the Layla album, instead handling the solos Clapton gave him in his own style.

Eric Clapton: I had a good time doing it. It was when I listened to the tapes afterwards that I realised that it was well under par. Everyone made mistakes.

The Rainbow shows might have brought Clapton out of his self-imposed exile, but they were less successful at helping him clean up. By the autumn of 1973, he and Ormsby-Gore had sunk ever deeper into their addict lifestyle at Hurtwood Edge. It took the intervention of Alice’s father, former Tory MP Lord Harlech, to bring them back from the brink, with help from Harley Street surgeon Dr Meg Patterson.

Eric Clapton: Alice’s father had discovered Meg Patterson and her form of acupuncture treatment. And then, for some reason, I just said: “Okay, I’ll give it a try.” And next thing you know, a very big emotional thing happened to me and I started to really want to live again. When you take a lot of heroin for a long time, you cut down on your ability to feel, your sensitivities shut down, you don’t feel emotions.

Dr Meg Patterson: All drugs were banned from the start of the treatment. We had the co-operation of Lord Harlech and Eric’s manager, Robert Stigwood, who said he wouldn’t give them any money to buy it.

Eric Clapton: Three times a day, one hour per session. It’s a box that has two cables leading out of it, with little metal clips on the end which you attach to your earlobes. The current runs through your head, then out the other side and back into the machine, and the pulse is controllable by a knob. You take it up to the threshold of pain and then take it down again. The cure itself was a combination of things… the acupuncture and the determination to get through it.

Clapton’s Harley Street treatment was a success, and by April 1974 he had kicked heroin. Unfortunately, during this period he began drinking heavily. To add to the chaos of his life, Boyd had left Harrison, eventually taking up with Clapton.

Eric Clapton: I came straight off heroin into drinking. It was essential. Woke up most days with a hangover.

Steve Turner (journalist): Eric told Robert Stigwood he wanted to make an album. Which turned out to be 461 Ocean Boulevard.

Eric Clapton: I’d been quite seriously addicted to heroin, then thought I’d got off it by drinking, not knowing that alcohol was probably going to do me more damage. I was so drunk on some stages that I played lying on the stage, flat on my back, or staggering around wearing the weirdest combination of clothes because I couldn’t get it together even to dress properly.

Yvonne Elliman (vocalist): That tour was drowned in alcohol. We were all a bunch of lunatics and we were falling into the rock-band ritual where you break things in hotel rooms and you throw food at each other and you release everything.

Eric Clapton: In that year I became a full-blown alcoholic. I’d have a bottle of vodka, a cassette machine, a guitar and a shotgun as my playthings at bedtime. And everything would be the same next morning, except the bottle would be empty. One of the things I used to do was put the shells in the gun and click it shut, and I’d put it in the position with the barrel to my mouth where you could take the top of your head off. And I thought: “Yeah, but if I did this, then I’d not be able to have another drink.” Now that’s what I’d define as insanity.

What happened next?

The two shows at the Rainbow may have proved a false dawn for Clapton, but they were recorded for a live album, released as Eric Clapton’s Rainbow Concert in 1973.

Clapton eventually married Pattie Boyd in 1979. He didn’t kick booze until 1981, after being hospitalised in the US with bleeding ulcers, forcing him to cancel an entire tour. He subsequently founded a rehab facility, the Crossroads Centre, on the island of Antigua.

Sources: Clapton, The Authorised Biography by Ray Coleman (Sidgwick And Jackson, 1994), Crossroads by Michael Schumaker (Hyperion Press, 1995), Conversations With Eric Clapton by Steve Turner (Abacus, 1976), Wonderful Today, by Pattie Boyd with Penny Junor (Headline Review, 2007), Ronnie by Ronnie Wood (McMillian, 2007).