“Steve Harris of Iron Maiden loves A Passion Play. I’m glad someone liked it!” Every Jethro Tull album in Ian Anderson’s words

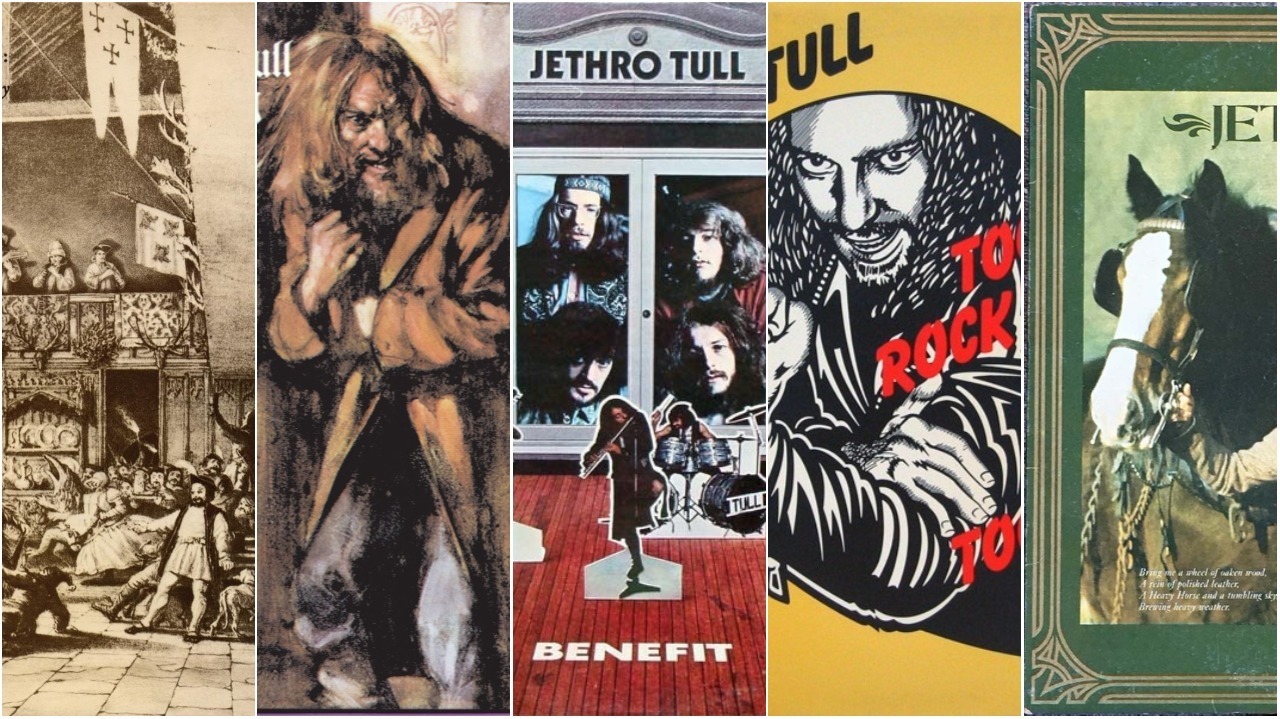

The coming-of-age one, the darker one, the singer/songwriter one, the step-too-far one, the kind-of-okay one, the odd one, the mainstream one…

In 1968, Ian Anderson released the first Jethro Tull album. Over that time, the band’s sound has evolved and diversified, but they remain an enduring touchstone of the prog rock world. In 2018 – before to the release of 2022's The Zealot Gene – Anderson looked back with Prog on Tull's studio output from 1969 to 2003.

This Was (1968)

“It’s all in the title, isn’t it? This was Jethro Tull. That’s no accident because when we were recording it, the one thing I felt sure about is that if we were lucky enough to make another album, I knew it wouldn’t be like this one: based on blues elements and black American folk culture. That’s not part of my life and I couldn’t keep doing that – I’d look like a complete twit. The cover had no logo or anything and people were telling me we couldn’t do that, but we did it, of course.”

Stand Up (1969)

“The coming of age, in a way. The birth of more original music for us. It was then that what was referred to as progressive rock music was coming into being. If it’s in that vein, it’s rock music rather than folky, but it’s progressive in that it reflects more eclectic influences, bringing things together and mixing and matching and being more creative. For me, it’s a very important album, a pivotal album.”

Benefit (1970)

“A darker album. You have to put that into the context of a band returning from the first of three forays into the USA and that altered my mindset. It’s not all gloom and doom, but it’s a slightly more oddball album. On For Michael Collins, Jeffrey And Me, we referenced Michael Collins, the astronaut who was stuck in the command module and we now know was given the instructions to leave the others behind. The loneliest man in space, and also he gets no glory because he’s not the guy who walked on the moon.”

Aqualung (1971)

“That’s the singer/songwriter side of things, where a lot of the music did come out of me strumming an acoustic guitar with a view to keeping it that way, as opposed to writing that way and turning it electric. That big title track riff came out of an acoustic jam – you’ve just got to have that imagination to hear that. You have to know that you can make it sing. It went on to sell and sell across the world. It’s the album that broke us in countries beyond the UK and US.”

Thick As A Brick (1972)

“After Aqualung, I felt we had to take a big step forward. Many writers wrote about Aqualung as a concept album, and I kept saying, ‘Maybe two or three songs in the same area, but not a concept.’ In the wake of all of that, I thought, ‘Right, let’s show them what a concept album is,’ and it seemed like an amusing idea to go down that route in this Pythonesque way and to try to use surreal humour. It clicked in America, which was a surprise, and it was our first real foray in that sort of theatrical presentation.”

A Passion Play (1973)

“The ‘step too far’ album. We decamped to the Château d’Hérouville in France where Elton had recorded, and had a rotten time: technical issues, gastric bugs… we just wanted to go home. So we did, and had a frantic few weeks of writing a new album. Two pieces made it on to the War Child album and one or two morphed into something more sophisticated, but they never came to light on that album. Steve Harris [Iron Maiden] loves A Passion Play. I’m glad someone liked it!”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

War Child (1974)

“It’s kind of okay. The big one on that was Bungle In The Jungle, which is a complete rebuild of a song from the Château tapes. Very much rewritten, but it used the reference of people behaving like they’re animals in the jungle. It was written to be a radio hit, and in America it nailed it – we got AM radio play, which opened us up to a much wider audience and brought a lot more people into the concerts. It had its moment. Ritchie Blackmore has a soft spot for that album, for some reason.”

Minstrel In The Gallery (1975)

“That’s an odd one. It’s the last one that Jeffrey Hammond [bass] played on, so it has this negative undertow to it as we knew he was going. So with Jeffrey leaving, it made me think, ‘Maybe I need to do this without relying on others so much.’ I started working more on my own in the studio, writing and recording, playing to a click track, so a lot of it was a bit more ‘them and me’ – a bit more insular, musically speaking, which wasn’t great in the spirit of working together.”

Too Old To Rock’n’Roll: Too Young To Die! (1976)

“The title track came to me on a plane journey when I was in heavy turbulence and very frightened. It was a piece about the kind of 50s Brit rock’n’rollers. Those bikers in that era, it was their world and they were already pushing 40 or 50 by then. You could mock that but there’s something rather noble and determined and dignified about it, and I just wanted to explore that dichotomy. It’s wistful and nostalgic and also a bit of a put‑down, and it’s finding that balance in a song sometimes.”

Songs From The Wood (1977)

“More than any album we’ve done, this is one where the band had more to do with the elements of the songs. Martin Barre [guitar] and Dee Palmer [keyboard] particularly had worked some material up that would fit right into a song, and where the recording process had all the band involved. There was an exception or two – Jack-In-The-Green was me one Sunday after lunch in there alone – but the rest of it was all of us. I feel perhaps since the days of This Was or Stand Up, it had much more of a band vibe. It was good.”

Heavy Horses (1978)

“You have to remember, this was at the time punk’s final embers were burning out and you had bands like The Police and The Stranglers, who were, collectively speaking, a bunch of old hippies. The brave new world of punk rock had perhaps become commercialised at that point. But bands like those two used punk as a means to get their foot in the door, just as I did with the blues in 1968.

“So from our perspective then, it wasn’t that we were vindicated that this new, intrusive music form had somehow ousted us from the public eye and approval, it was just a parallel event. I don’t really recall being moved as a music maker by any of those changes in music that were going on. I knew what it was about and I rather liked some of it, but it was entirely separate to what I was writing. I didn’t want to try to catch up or be influenced by it. We were still making Jethro Tull albums at that point.”

Stormwatch (1979)

“There was a lot of stress within the band, mainly to do with John Glascock’s illness [the bassist had heart problems]. We sent him home and told him he had to get out of this spiral he was in because it wasn’t just his illness, it was lifestyle. He’d be on stage and his face would be white like wax, with a film of sweat. I made him leave to get himself well and sadly he got worse and then we got the terrible news that he’d passed away. Did we do everything we could to help? That’s a question we’ll ask ourselves forever.”

A (1980)

“It was as simple as A for Anderson because it was supposed to be a solo album. I wanted to take some time out and I asked Eddie Jobson to be involved, so we started in the studio. I heard this guitar line in this bit I’d written and I called Martin Barre and he ended up staying. Then the record company said, ‘It sounds like a new Tull album,’ and I regret giving in to that. It sits there on the edge of our repertoire: it’s quite the mainstream thing.”

The Broadsword And The Beast (1982)

“That followed a bit of hiatus and we were getting towards the end of the record, and I thought, as I have before, ‘I’ve spent so much time with this material, I’d really like someone else to come in and mix.’ We found Paul Samwell-Smith, who we knew from The Yardbirds, and he came in towards the end and took a lot of pressure off me. We worked well together – we had this good accord and bounced off each other very well. I’d been feeling very pressured on the previous albums, nursemaiding everything to the end.”

Under Wraps (1984)

“That was following my solo album called Walk Into Light [1983] where I’d been exploring what was then the new technology of the emerging world that was moving from analogue to digital – drum machines, very primitive sequencers and so forth. I thought we could use that on a Tull album. It’s got some great songs and it’s arguably the one album where I really pushed myself as a vocalist. It’s a great album apart from the drum machine – it annoys me to this day, and the public didn’t like it either. I’m glad I did it though.”

Crest Of A Knave (1987)

“I was going out and doing Under Wraps [1984] live, and I ripped up my throat – I couldn’t sing and I thought maybe time was up and I’d blown my voice completely. I spent a year not doing anything but seeing throat specialists, so it wasn’t until the summer of ’86 that we went out and did some shows, including one in Budapest where I wrote the song of the same name. In America it was the early days of MTV and Steel Monkey got quite a lot of prominence. That album did well in the US and won the Grammy.”

Rock Island (1989)

“The antidote to the more cheerful Crest Of A Knave, it’s mostly dark subject matter of alienation and desolation, except for the absurd Kissing Willie – an all-too-regrettable, unsubtle piece of saucy innuendo. Benny Hill would have been proud of that one. But the song Strange Avenues is still a favourite of mine. And Another Christmas Song too, which talks of origins and cultural identity. ‘Everyone is from somewhere, even if you’ve never been there.’”

Catfish Rising (1991)

“A rather good collection of songs, but at a time when Tull weren’t exactly in fashion! Some people felt it went back to our bluesy base – maybe too much for one reviewer who referred to it as ‘cod blues’. This Is Not Love, Still Loving You Tonight and Rocks On The Road stand out for me. A lot of this was recorded alone in my studio with overdubs from Martin [Barre] and [bassist] Dave Pegg. The worst thing about the record was the album cover. Too much black! Too much Spinal! No space to sign autographs with a black Sharpie.”

Roots To Branches (1995)

“The last album with Dave Pegg who played, I think, only on three tracks due to the resurgent popularity of Fairport Convention – always his first love – and the increasingly difficult task of being the bass player of two bands at the same time. All the songs on this record still work for me. We enlisted American jazz rocker Steve Bailey to play bass. He turned up on a freezing January morning to start work on the record in my new studio. These days he’s Chair of Bass at Berklee College.”

J.Tull Dot.Com (1999)

“With the advent of the internet, I thought we should have our own website. After some legal arm-wrestling with the cheeky owner of the name www.jethrotull.com, I beat him into submission in a Swiss court and got the name freed up for our use. The title track stands out, along with Hunt By Numbers and Wicked Windows – a reference to the heinous Heinrich Himmler of the bespoke dodgy specs. I was in the Auschwitz museum recently where the glasses of many incoming prisoners are on display. I thought of him while I was walking around. A lot.”

The Jethro Tull Christmas Album (2003)

“When the record company suggested we do a Christmas album, my immediate reaction was no, but I started to wonder if there was a way to do something not altogether cheesy and trivial. So I came up with some variations on Christmas carols, looking at the ‘other side’ of Christmas. Some Tull material was re-recorded as I already had a few pieces in the repertoire that touched on the spirit of winter. Birthday Card At Christmas is special for me as my daughter’s birthday is on December 22 and it tends to be glossed over in the days before Christmas.”

Philip Wilding is a novelist, journalist, scriptwriter, biographer and radio producer. As a young journalist he criss-crossed most of the United States with bands like Motley Crue, Kiss and Poison (think the Almost Famous movie but with more hairspray). More latterly, he’s sat down to chat with bands like the slightly more erudite Manic Street Preachers, Afghan Whigs, Rush and Marillion.