It’s a balmy Saturday night in Los Angeles, and Row 9 on the floor of the LA Forum is drummer heaven – or maybe drummer hell, depending on your viewpoint. Chad Smith of the Red Hot Chili Peppers stands next to the Foo Fighters’ Taylor Hawkins. A few seats along, Tool’s Danny Carey is engaged in conversation with current Queens Of The Stone Age man Jon Theodore.

Like the 17,000 other people in attendance, they’re here to see Rush bring their sold-out R40 ‘anniversary’ tour to a close (in typically perverse Rush style, it’s actually 41 years since they released their debut album). But there’s one particular thing onstage that has them rapt, eyes front and centre: Neil Peart.

As Peart thunders into Overture from the Canadian trio’s breakthrough album 2112, the gaze of all four drummers instantly snaps stagewards, like dogs who have spotted a biscuit. The object of their attention rattles across his seemingly endless parade of tom-toms as the band segue into Temples Of Syrinx, and 17,000 pairs of air-drumming arms shoot ceiling-ward. None are more animated or as on the beat as Smith, Hawkins, Carey and Theodore.

A couple of hours later, Smith is enjoying the hospitality at the post-show end-of-tour party and recalling his indoctrination into the Cult Of Rush as a teenager. “I spent my sophomore year of high school in the parking lot, smoking weed and listening to 2112,” he says. “That’s when my Rush education began. I do believe it’s a prerequisite for all rock drummers to go through a Neil Peart phase.”

It’s not just a drummer thing. Matt Stone, the co creator of South Park and a close friend of Peart, is equally effusive. “Totally amazing show!” he says, waving his drink around for emphasis. “I invited a couple of friends of mine that I grew up with in Denver. We saw Rush in 1985 at McNichols Arena, and it was really cool to bring it full circle here in 2015.”

There’s a lot of talk about things coming full circle tonight. If recent proclamations by certain band members are anything to go by, then this tour – and specifically this show – represents the end of Rush as a touring entity, if not the end of Rush full-stop. Peart has made it clear that he’s tired of the physical and mental toll that playing live night after night takes. There are no more shows scheduled following the LA gig, either in the US or Europe. Asked recently whether this would be Rush’s swansong tour, guitarist Alex Lifeson replied: “I don’t think we’d have much difficulty thinking about it as possibly the last.”

Remind Geddy Lee of this and he laughs. “That’s not true,” says the bassist and singer. “I’m having great difficulty thinking like that. Alex is not speaking for me, and I don’t think he’s really speaking for himself either. I think he has mixed feelings. I don’t want to speak for him. You can ask him. He can tell you his own lies.”

It’s three days before what may or may not be Rush’s final show, and Lee, Lifeson and Peart are moving in slightly more rarefied circles. The three of them have convened at the Canadian consulate in LA, where a reception is being thrown in their honour. The Consulate is bestowing its very first Honoree For Canadian Excellence award on the band, thanks in part to the fact that they have played Los Angeles 36 times over the years (it also happens to be Lee’s 62nd birthday).

In the landscaped gardens at the rear of the well-appointed house, half a dozen tables have been set up for a dinner. The band members all sport the Order Of Canada pins they were awarded in 1997. Their families are here, as is their long time manager, Ray Danniels, South Park’s Matt Stone and actor Jack Black, the latter of whom spends the evening glad-handing other guests and demanding to know, technically speaking, whether we’re in Los Angeles or Canada. As the band are introduced by genial Consul General James Villeneuve (“Ray Danniels tells me the R40 cake I made contravenes some kind of copyright”), the assorted guests laugh good-naturedly. Glasses are raised and toasts are made, before Lifeson steps up to speak. “I’d just like to say, ‘Blah, blah, blah…’” he begins, a knowing nod back to his infamous Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame speech.

There’s some irony to this, at least when it comes to Neil Peart. The drummer, who has lived in California with his second wife, Carrie, for the better part of 15 years, was recently granted American citizenship. “Why did I take it?” he says, as we top up our glasses at the makeshift bar. “I found out that if you’re an American citizen, they can’t deport you.” He does an exaggerated double take at his lapel. “Though at any moment now, I’m expecting to be thrown to the floor and have my Order Of Canada ripped from me.”

He’s in high spirits, though that’s hardly surprising. Of the three members of Rush, he’s the one who seems most relieved that this journey might be coming to an end. Later in the evening, he’ll tell Jack Black that it’s over for him, as Black’s eyes get wider and his jaw slackens with disbelief.

Ray Danniels has mixed feelings about it all. He started out booking the band into bars, high schools and drop-in centres in and around Toronto in the early 70s, before going on to become their manager.

“I don’t think they should end,” he says, sipping white wine at the pool’s edge, when the inevitable question of whether this is the end of the road for Rush is broached. “They are playing as well as they ever have. Shorter tours, longer breaks, more days between shows, shorter sets, opening acts or just one last hurrah would be my vote. A lot of people wanted to see them that didn’t get a chance to. That said, I know you can’t perform this at this level of intensity indefinitely, but I would explore ways to make it work for a little while longer while it’s this good. It matters to a lot of people. That’s my honest feelings.”

He looks across the still pool of blue water where his band are laughing it up some twenty feet away. “But then I’m not the one on stage feeling any pain or the ravages of time. I’m in the house loving it with 14,000 other people most nights.”

Irvine is a two-hour-plus drive from Hollywood down Route 101, one of Southern California’s most congested highways. Even in the assigned car pool lane, the flow of traffic is sluggish. Outside our SUV, everything looks bleached in the bright Californian light. Inside, the only sound is the steady thrum of the AC set to stun. Geddy Lee looks distractedly at his phone, keeping an eye on the score in the game between his beloved baseball team the Toronto Blue Jays and the Kansas City Royals. Tonight’s gig, at the Irvine Meadows Amphitheatre, is the penultimate date of the tour. In two days’ time, Rush will take their bows at the Forum. Whether that’s for good or not, not even Lee can say.

“How am I feeling? Sad, sad,” he says, his voice hoarse with the vestiges of a cold he’s been fighting off for the last few weeks. “The tour’s gone so well. I’m really proud of it – we’re playing really well. I love the way the show has lived up to my expectations and I’d just like to keep going. I think a lot of the fear before the tour was that Alex’s arthritis would interfere with his playing and he wouldn’t be able to deliver. Rehearsals were a little shaky, but once we got past the first leg, I think he hit his stride and he’s ripping every night. That makes you feel, ‘Yeah, I can do this.’”

Lifeson’s arthritis is one of the main factors in Rush’s future, or potential lack of it. Earlier this year, he told Classic Rock that he has suffered from arthritis for the last 10 years.

“I am hurting a little, but it doesn’t bother me – everybody has aches and pains,” the ever-buoyant guitarist says today. “I think that if it was really slowing me down and quite critical in my playing then it would be a different story. My hand is sore after a show, like it never was before, but it’s not a big deal. Take a couple of Tylenols and power through it.”

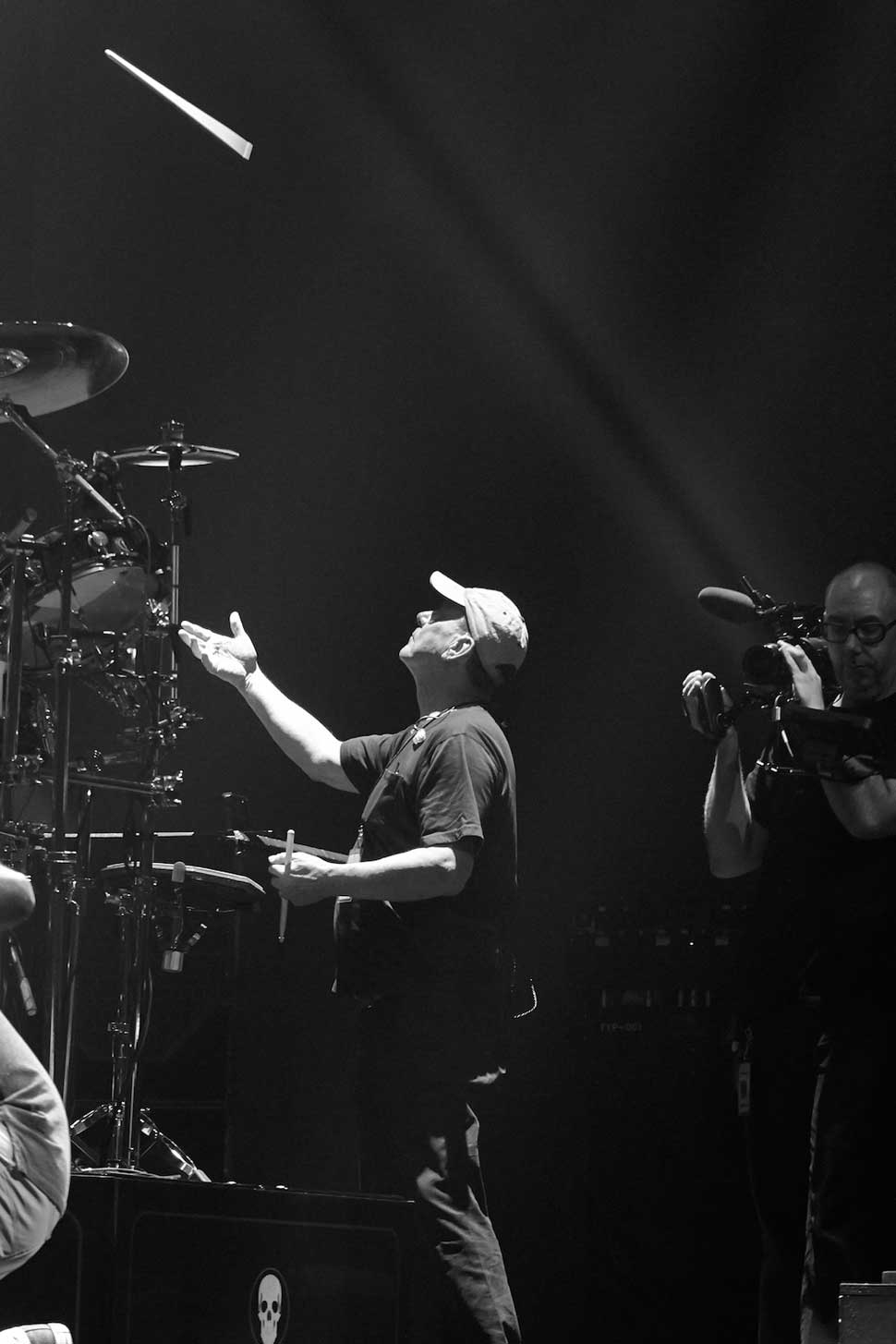

It’s soundcheck time at Irvine Meadows and the two of us are standing in the wings of the stage, trying not to overheat. Crew sporting T-shirts emblazoned with the legend ‘Blah Blah Blah’ in the same typeface as the logo from Rush’s self-titled debut album busy themselves as only roadies can. Neil Peart sits behind one of the two kits in the centre of the stage – he plays a different set in each half of the show: one his current Clockwork Angels drumkit, the other a replica retro kit. He throws drumsticks distractedly into the air, catching them as they fall.

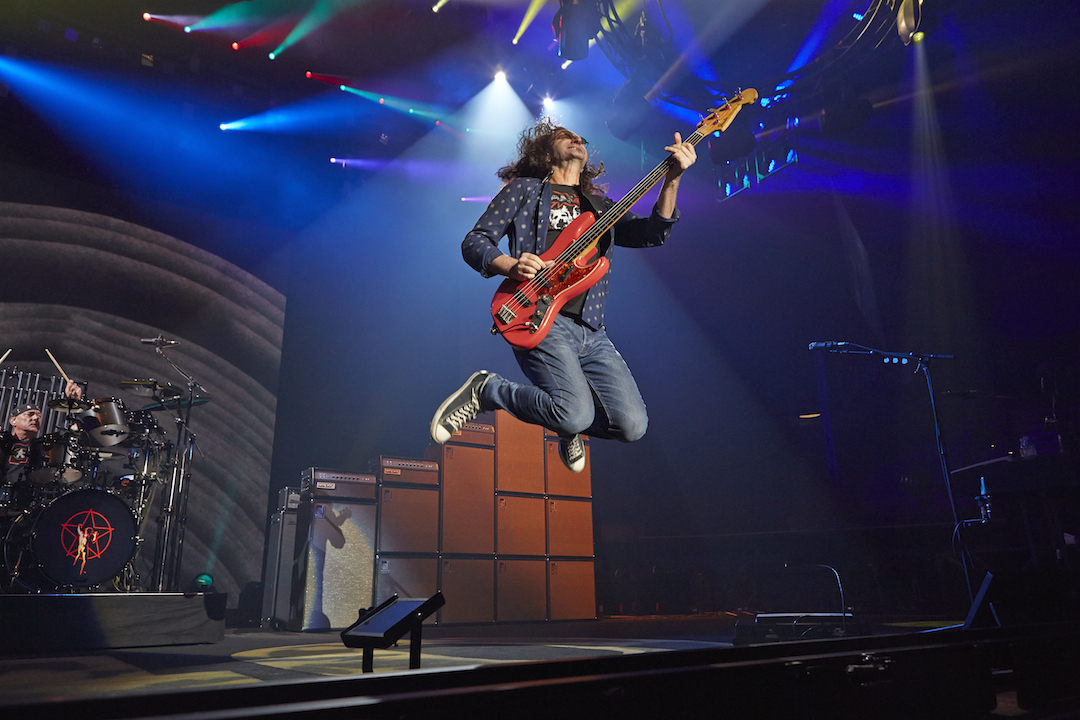

Lee’s side of the stage is home to a bewildering array of bass guitars, many of them collector’s items. He’ll change instruments 25 times during the three-hour show. At soundcheck alone, his tech, Scully, hands him three different guitars. They run through Subdivisions, its washes of sound bouncing around the empty arena. Its followed by 1978’s Jacob’s Ladder, still sounding eerie in the arid heat of the day. As it shudders to a halt, Peart happily exclaims, “Shut up!” and the three of them wander off for what might one of the last dinners they have together as a band.

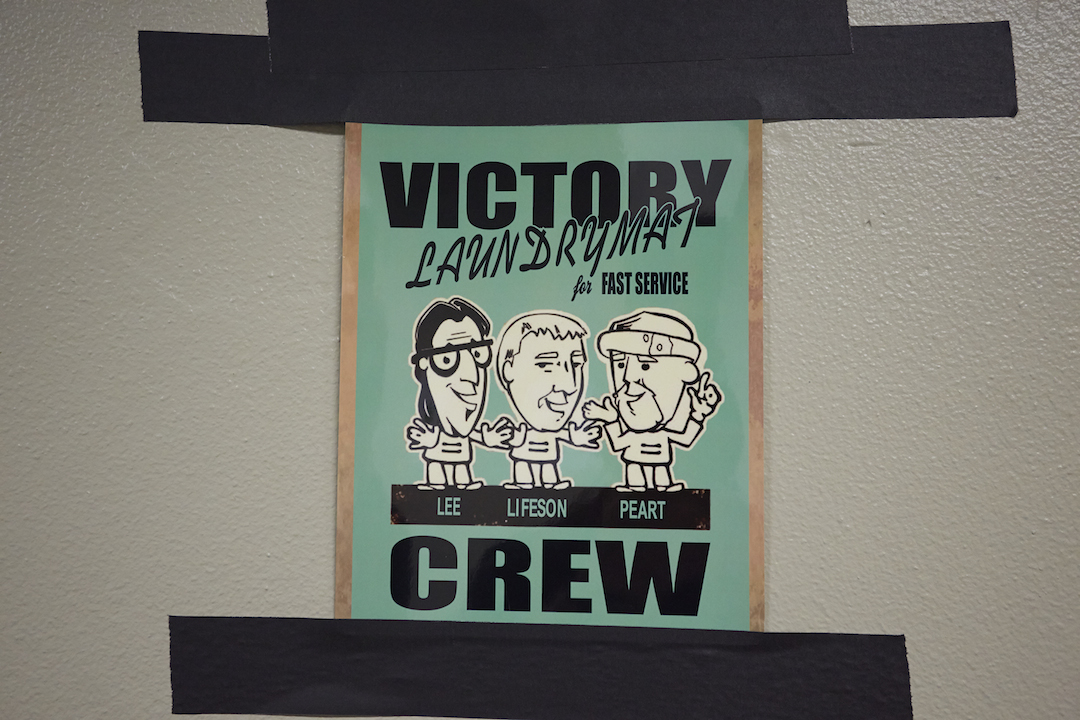

As this tour draws to its close, the crew are handed end-of-tour gifts: beautifully boxed Tag Heuer watches with the band’s logo and signatures etched onto the wristband. (To give you an idea of the scale of it, the R40 tour includes two carpenters just to accommodate Lee’s ever-changing backline of popcorn makers and washing machines.)

It’s a cliché, but there’s a sense of family to it all, which is largely down to the fact that many of these people have grown up together. Take Howard Ungerleider, the man responsible for the band’s spectacularly inventive light shows. He began working with the group in 1974 as their joint tour manager, lighting director and accountant.

“I’d been around, collecting money, making sure the band got paid, making deals, you know,” says the amiable yet gruff-sounding Ungerleider, who was working for the American Talent International agency in New York – who represented Savoy Brown and Fleetwood Mac, among others – when Ray Danniels signed his band with them in 1974.

“When I met them, they were in-between drummers and they had zero experience of touring. They sent me in there to take them out and make sure they knew the ropes. But when I first saw them in rehearsal, they had a power, and you could see it connect with the audiences almost instantly. I always felt they were going to be successful. I actually told Geddy’s mother that off the first tour. But that successful? No one expected that. When it came, it was so unbelievable.”

As well as Geddy Lee’s birthday, the night at the Canadian embassy marked another, no less crucial anniversary: the 41st anniversary of the day the band hired Neil Peart. Ironically, given Peart’s role in the band’s subsequent development, it nearly didn’t happen.

“We tried to poach Max Webster’s drummer and he said yes, and then a few days later he said no,” says Lee. “So that’s why we had the auditions. Neil was the third guy to come in and I felt for the fourth guy having to follow Neil: who’d want to be that guy? I felt so bad for him because he had written charts of the first album and he was sitting there playing while reading the charts and he was very polite and we had just experienced this whirlwind that was Neil…”

A week later, the newly reconfigured Rush were opening for Manfred Mann and Uriah Heep in Pittsburgh. “That was our introduction to touring,” says Lee. “It was the end of Uriah Heep’s tour so we were seeing all kinds of shenanigans backstage on the last gig. They had flocks of groupies hanging around, they were all throwing cream pies at each other on stage. We were like, ‘This rock’n’roll thing is cool.’ There was women and pie. I don’t know what we were more excited about.”

They played a ragtag mixture of tours and gigs after that, frequently opening one-off shows with what the bassist calls “strange, terrible combinations”. One of these was Sha Na Na, the New York rock’n’roll revivalists best known as the band who played at Woodstock just before Jimi Hendrix. “We did 30 minutes and got booed for pretty much all of that,” says Lee with a laugh. “Probably the worst thing we did in terms of the response we got.”

Almost as memorable for the wrong reasons was the band’s return to Pittsburgh. This time they were opening for Blue Öyster Cult. “The gear got there late for some reason, so they cut our set back to 10 minutes. We played Finding My Way and Working Man, then ‘Thank you, goodnight!’”

Lee says there were “rumblings” last summer that this could be Rush’s last tour. But Peart’s reluctance to commit threw things into doubt.

“I just shelved everything because I didn’t think the tour was going to happen. And when we did finally get together in November, after Alex had his surgery [the guitarist had been hospitalised for anaemia from bleeding ulcers, and suffered breathing problems after it was discovered his stomach had drifted upwards and settled behind his heart], Alex said he wasn’t sure about how he would recover and he was not feeling at the top of his game. He expressed the feeling that if we were going to do it, then he’d rather tour sooner than later. He was worried about how his arthritis would be in two years. Neil said, ‘That’s the one request I can’t say no to. If Al wants to do it now, then let’s do it.”

Two days later and the R40 tour – and maybe Rush themselves – is drawing to a close. The trio first played the LA Forum in 1976, in support of 2112. Tonight will be the 25th time they’ve played here. The load-in ramp to this cavernous venue made a cameo appearance in the Cameron Crowe movie Almost Famous when Kate Hudson’s character, Penny Lane, strides onto the screen and out into the Forum’s vast car park.

In the backstage area – a warren of seemingly endless corridors and boxy rooms – the mood is less celebratory than it was at Irvine two nights ago. Geddy Lee is quietly affable, but Neil Peart is stone-faced and mute in the band’s dressing room.

Lee’s wife, Nancy Young, is here as well. Nancy hasn’t been to a band soundcheck in some twenty years, maybe longer, but she’s making an exception this time.

“You go out to soundcheck when you’re young and in love,” she says with a laugh. “It’s been so long since I’ve been to one of these, people are asking me what I’m doing here today. What do they think I’m doing here? It’s just hit me – this might be it and for forty years this has, for the most part, been our life.”

Fittingly, the R40 show is a journey back in time. The band begin with songs from their most recent album, Clockwork Angels, and work their way backwards through their catalogue, until they end at the beginning with a histrionic Working Man. As they play, the stage show devolves around them: backlines rise and fall, lighting rigs diminish in size, twin-neck guitars are revived for Xanadu, until we finally arrive in a school gymnasium in the early 1970s, Lee with a solitary bass amp perched on a chair behind him, two slim towers of light flanking the band. It’s easy to imagine that you’re watching a band come full circle one last time, addressing their history before saying goodbye.

“It looks that way,” says Lee. There’s a long pause. “The idea was appropriate enough for a retrospective. The fact that it may or may not be the last tour makes it more poignant, but that wasn’t the purpose of it. I loved the idea of finishing the show in our earliest, most simple state.”

After Working Man draws to a close, the giant screen that shrouds the stage descends for the outro film. It starts off with a series of outtakes of the band hamming it up, before it jumps to Lee shouting, “Thank you, goodnight!” from different stages and times around the world. It’s an emotional moment that’s almost unbearable to watch. Some members of the crowd are shouting themselves hoarse while others are clearly in tears.

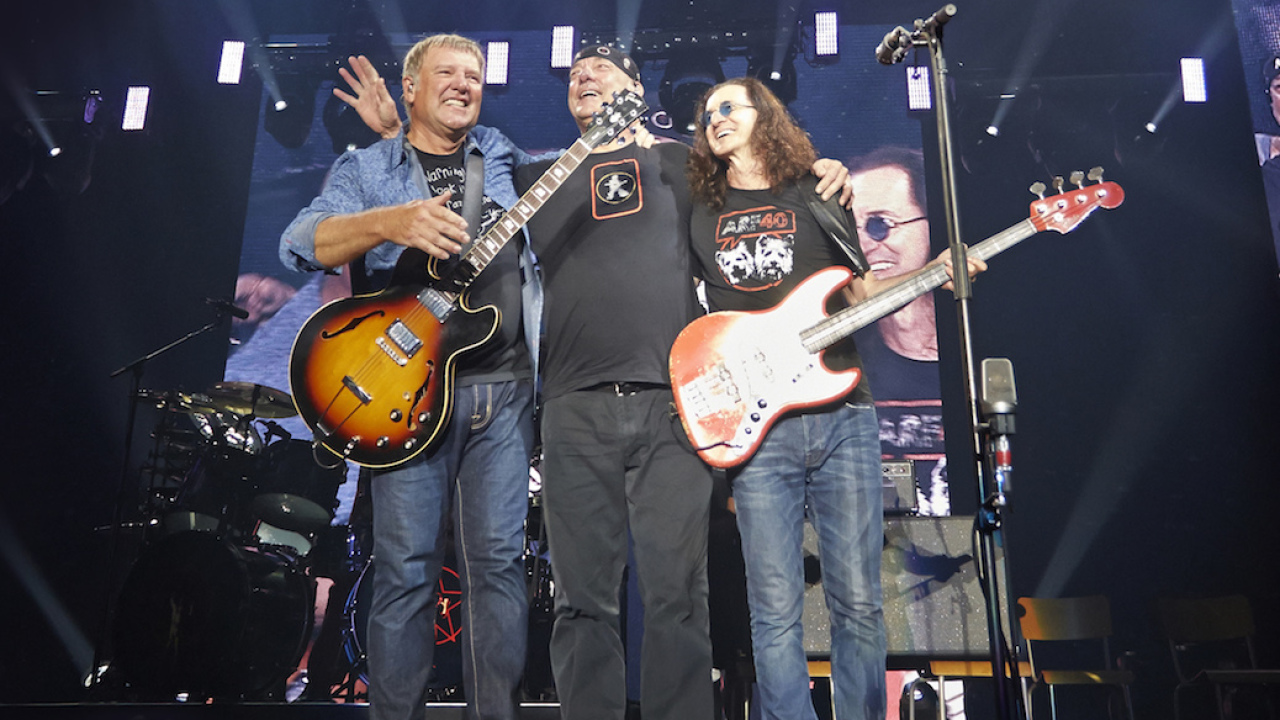

The film plays out with one last gag that involves the band being barred from their own dressing room by the puppet from the cover of 1977’s A Farewell To Kings album, while various characters from other album sleeves party behind him. The dressing room door shuts hard, leaving Lee, Lifeson and Peart to walk dejectedly down the bare arena corridor and into the long shadows. As the film ends, Lifeson turns to his bandmates, shrugs and asks: “What now?”

Right now, it’s a question that none of them can answer.

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 215, in October 2015.