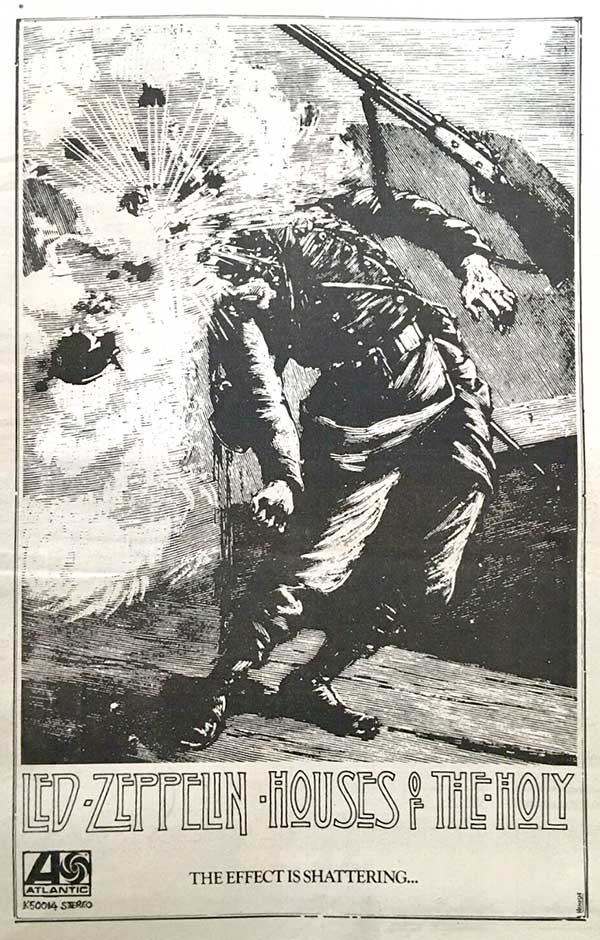

In March 1973, adverts started appearing in the music press for Led Zeppelin’s new album, Houses Of The Holy.

One featured a black-and-white drawing of the kind once found in the pages of a Victorian ‘Penny Dreadful’ magazine. It showed a man with his hands bound behind his back and his head jammed between the buffers of two railway carriages. Another featured a uniformed figure with their head exploding in a cloud of smoke and flames, above the words: “LedZeppelin. Houses Of The Holy. The Effect Is Shattering…"

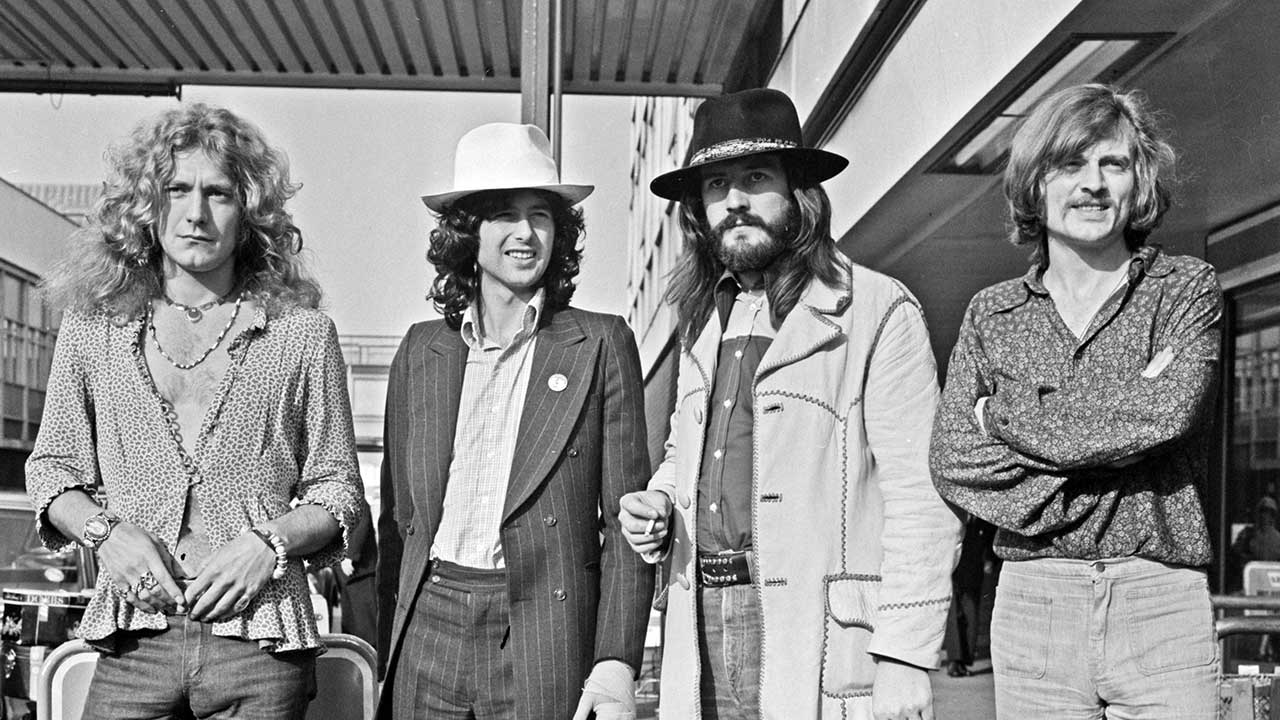

Even ads for Pink Floyd’s enigmatic-looking new album The Dark Side Of The Moon, released that month, couldn’t equal the confidence of Zeppelin’s campaign. Since 1971’s fourth album, they had dispensed with images of themselves on album sleeves. Now, they no longer needed a band picture or even an album cover in their ads; the crushed skull and exploding head did the job just fine. Released on March 28 1973, Houses Of The Holy rapidly topped the UK and US charts.

In truth, Houses Of The Holy is a more subtle record than that schlock-horror ad campaign suggests. Yes, it’s a bit messy and almost perversely eclectic, but it also contains at least four classic songs (five if you’re in the mood for a good pub argument).

Taken as a whole, it bottles Zeppelin’s gleeful energy and anything-goes experimentalism just at that point before they became the biggest rock group on the planet. Zeppelin’s fifth album always gets passed over for their fourth, with its ubiquitous Stairway To Heaven, or ’75’s magisterial Physical Graffiti. But Houses Of The Holy is the sound of a band entering their most imperial phase, just before fatigue, cynicism and hard drugs impinged on their well-being.

In a strange way, it’s Zeppelin’s last ‘innocent’ album – if anything about Led Zeppelin could ever be described as innocent.

Although they’d emerged in 1968, Zeppelin were always a band for the 70s. Jimmy Page had toured America with his old group The Yardbirds. There, he’d spotted a gap in the market for a band that could build on the power and dynamism of Jimi Hendrix and Cream.

By the end of 1969, rock music had become big business. Critics mourned the end of the hippie dream and the rise of the ‘breadheads’. But there was now a new audience to be catered for: teenagers who had been too young for the Summer Of Love and wanted their own heroes. There were arenas to be filled and dollars to be made.

Led Zeppelin saw their chance, and took it. Rolling Stone critic John Mendelssohn described their self-titled 1969 debut album as “weak, unimaginative, limited, monotonous”, sparking a tense relationship between the band and the press that was never resolved.

But Led Zeppelin and its follow-up Led Zeppelin II both cracked the Top 10 in Britain and America. Those who dismissed the group as stone-age grunters were further disarmed by 1970’s Led Zeppelin III, which included a clutch of almost tender folk songs. It proved, said Page, “that there is another side to us”.

This message was driven home on 1971’s fourth LP (the one most people call Led Zeppelin IV). Its centrepiece, Stairway To Heaven, conveyed more of the band’s light and shade, and became a hit on US FM radio.

Zeppelin’s refusal to release singles, together with their reluctance to woo the press, all added to the mystique. IV went gold on the day of its release. But by the time they started Houses Of The Holy, the stakes were higher than ever. “We wouldn’t make the same record twice,” said Page. “It was a case of: ‘Let’s keep moving.’”

Work began on the album in April 1972 at Mick Jagger’s Berkshire manor house, Stargroves. The Rolling Stones had moved to France a year before to avoid Britain’s punitive new tax laws and make Exile On Main Street. The four members of Zeppelin shipped over to Stargroves to rehearse and record their new material.

“It was a nice mansion, if you like mansions,” engineer Eddie Kramer told Zeppelin biographer Barney Hoskyns. Kramer showed up at Stargroves with an American girlfriend in tow, but “Robert Plant bagged her straight away”.

Meanwhile, Page bagged Jagger’s bedroom, one of the few furnished rooms in the house, and Bonham’s kit was set up in a large, conservatory-style space downstairs. When the group wandered outside, Kramer recorded Plant singing and Page strumming an acoustic guitar in the sunshine.

“You can hear the fun we were having,” the guitarist said. “And you can also hear the dedication and commitment.” Dedication and commitment were never a problem for Page.

“I don’t think Zeppelin was ever complacent,” said Robert Plant. “By the time we got to Houses Of The Holy, there was a conscientious air about Jimmy’s work.”

Page had come to the sessions loaded with song ideas worked up beforehand at his home studio. One of the songs he brought to Stargroves would become the album opener. The Song Remains The Same started as an instrumental fanfare for the album’s second track, The Rain Song. Then Plant heard it.

“Robert had different ideas,” said Page. “He said ’This is pretty good. Better get some lyrics – quick!’”

Plant’s lyrics referenced Zeppelin’s globetrotting adventures, with ‘sweet Calcutta rain’ a nod to a trip to India the singer and Page had made before starting the album. Page’s jangling 12-string guitar created an exotic noise and sounded like a mini-orchestra. Plant’s voice was slightly speeded up. Listen to it now and it almost sounds like Yes. But that’s an (un)happy accident.

While progressive and glam rock were thriving in the outside world, Zeppelin created music in a bubble. Nothing ever seemed to make its way in, apart from the blues, soul and 50s jukebox records they’d grown up with.

The Song Remains The Same also had a cinematic, larger-than-life feel that Zeppelin would go back to on Achilles’ Last Stand, the dominant track on 1976’s Presence. But while the latter track sounded like the end of the world, The Song Remains The Same sounded like a band having the time of their lives.

Even the ballad, The Rain Song, all about a broken romance, didn’t sound that heartbroken. John Paul Jones created the song’s mournful violins and cellos with a Mellotron, that unwieldy, primitive synthesiser featured on the Moody Blues’ 1967 hit Nights In White Satin. But, as Jones dolefully recalled, “They had the guy who invented it working for them, and I didn’t.”

Jones did a sterling job. Never one for self-aggrandisement, it’s difficult to overstate his role on the whole album. He’s there throughout, sometimes in the foreground but more often than not multi-tasking at the back.

Jones also brought song ideas to Stargroves. One of these, No Quarter, the album’s only downbeat track, had been attempted during sessions for the fourth LP. Now, though, they found an arrangement that gelled. Between them, Jones’s grand piano, bass and synthesiser, Page’s eerie-sounding guitar, Plant’s treated vocals and a restrained John Bonham, conjured up a mysterious song about an unspecified snowbound rendezvous.

You never knew exactly what was going on, but whatever it was sounded dramatic and life-changing. No Quarter swept Houses Of The Holy out of the daylight and into the Arctic gloom. It was a brilliant counterpoint to everything else on the album. “I knew instantly [No Quarter] was a very durable piece and something we could take on the road and expand,” Jones told Zeppelin historian Dave Lewis.

You can only imagine how much it must have peeved him, then, when Page and Plant lifted its title for their Jones-less ’94 collaboration album, No Quarter: Unledded.

After further sessions at London’s Island and Olympic studios, with engineers Keith Harwood, Andy Johns and George Chkiantz, Zeppelin went back on the road in America in June. In between dates, they checked into New York’s Electric Lady studios with Kramer to mix the Strargroves tracks.

The band had worked hard to cultivate an aloof image, believing that it helped sales. But it also had a downside. By now, Zeppelin had notched up four UK and US Top 10 albums. But it was the Rolling Stones, not Led Zeppelin, who were bagging magazine front covers and having society author and social butterfly Truman Capote trailing them around America on tour.

“All we read was, the Stones this or the Stones that,’ John Bonham complained in NME. “And it pissed us off.” Perhaps that’s why Stargroves was never mentioned in the credits on the original Houses Of The Holy LP. The Stones may have stolen their thunder, but Zeppelin sounded invincible at their own shows.

“Right through, the majority of the music was built on an extreme energy,” explained Plant. That was never more apparent than at the LA Forum and Long Beach Arena on June 25 and 27 (two shows preserved on the 2003-released live album How The West Was Won). That “extreme energy” was further distilled on the three Houses Of The Holy tracks played during the gigs, despite the new album not being out for another nine months.

On Over The Hills And Far Away, Plant revisited the role he’d played on Led Zeppelin II’s Ramble On: the hippie romantic with a well-thumbed copy of The Lord Of The Rings under his arm, still trying to get into a fair maiden’s pants. After a deceptively folky intro, Page’s scything guitar blew the song out of Middle Earth.

Meanwhile, on The Ocean, a sort of heavy metal sea shanty, Bonham’s drum fills challenged the jabbing rhythms on Led Zeppelin IV’s Black Dog for sheer unadulterated power. The Beastie Boys would later sample Page’s opening riff on The Ocean for their own She’s Crafty in 1986 (the lawsuit-tempting rappers also sampled Bonham’s monster drum pattern from When The Levee Breaks on IV for Rhymin’ & Stealin’).

However, despite the song’s burly swagger, The Ocean’s lyrics had a twist. They weren’t about sex or hobbits, but partly inspired by Plant’s three-year-old daughter, Carmen. Houses Of The Holy has the distinction of being one of only two Zeppelin albums (the other is 1979’s In Through The Out Door) on which Plant doesn’t slip into caveman mode even once and sound like’s he’s coming to drag your daughter/mother/grandma back to his lair.

It’s a long way from here to, say, Physical Graffiti’s Sick Again, three years on, where he sings about a gang of predatory LA groupies. But Led Zeppelin’s world had changed by then. If one single song summarises the (almost) innocence of Houses Of The Holy, then it’s Dancing Days, also premiered at those ’72 shows, and one of the best Led Zeppelin tracks you’ll never find on any official ‘best of’ compilation.

Dancing Days was the goofy pop-rocker with the wonky guitar and organ riff (that man Jones again) that opened Side Two of the LP. Until that first round of Zeppelin CDs appeared, listeners kept the album’s inner sleeve/lyric sheet close at hand, to check that Plant really did sing: ‘I saw a lion he was standing alone with a tadpole in a jar.’ He did. Perhaps the clue as to why could be found elsewhere in Dancing Days’ talk of ‘suppin’ booze’. Either way, it was the brightest-sounding song on a very bright-sounding album.

Which just leaves the two tracks that have been polarising opinion for 40 years. Side One of Houses Of The Holy ended with a circular funk rock jam called The Crunge. Bonham and Page played as if they were reading each other’s minds, and Plant ad-libbed the vocal to which he added a James Brown pastiche (‘Has anybody seen the bridge?’).

The song baffled listeners not used to their long-haired, white rock bands playing dance music, even if Zeppelin’s definition of dance music (see also Physical Graffiti’s Trampled Underfoot) usually suggested a man dancing with one foot in plaster. The Crunge is no exception. Nowadays, though, it just sounds like “the giggle” that Page told the press it was. And besides, the riff is fantastic.

Unfortunately, the lilting lovers rock of D’Yer Mak’er, forever damned as ‘Led Zeppelin’s reggae song’, hasn’t weathered as well. The problem is that it wasn’t reggae enough, which was partly due to the rhythm section’s lack of conviction.

“John [Bonham] wouldn’t play anything but the same shuffle beat all the way through,” said Jones. “He hated it, and so did I.”

Page insisted pedantically that D’Yer Mak’er was “more a 50s thing” than reggae. Which is why the lyrics on the inner sleeve ended with the question: “Whatever happened to Rosie And The Originals?”, a reference to a 50s doo-wop ensemble; the kind of obscure group Plant has been dropping into conversation for years as a way of putting doltish rock journalists off their stride.

If you hear D’Yer Maker unexpectedly, it sounds better than you remember it. But even after all these years it’s difficult to love.

Houses Of The Holy was completed in August ’72. The sessions had proved fruitful, and there were several songs left over. The discarded title track (a bouncy pop-rock song and distant relative to Dancing Days), together with The Rover (another of Plant’s questing lyrics roped to a wonderful grinding guitar riff) and Black Country Woman (acoustic fun and games recorded on the lawn at Stargroves) were all carried over to Physical Graffiti. The other leftover, Walter’s Walk, only surfaced on the 1982 compilation Coda.

By the time Houses Of The Holy appeared in March 1973, Zeppelin were getting the begrudging respect that had been denied them for so long. After all, it was hard for the press to ignore them when all 24 dates on their November 72 UK tour sold out in four hours. HOTH itself went to No.1 on both sides of the Atlantic. Though not everyone was convinced.

It was an “an inconsistent work,” said the Disc And Music Echo, who were more impressed with that mystical sleeve featuring naked kids crawling over the Giant’s Causeway.

“So there’s some buggers who don’t like [the album],” shrugged Page. “Good luck to ’em. I like it, and a few thousand other buggers too.”

On May 5, Zeppelin broke US box office records playing to 56,800 at Florida’s Tampa Stadium. It was proof that they owned the post-Woodstock crowd. They toured with a private jet, groupies at their beck and call, and enough booze and drugs to make them think their heads had exploded – or, at least, been jammed between the buffers of two railway carriages.

Their story would get very dark very soon. But for now the sun was shining. Houses Of The Holy, the best Led Zeppelin album no one talks about, had helped make them the biggest rock’n’roll band in the world. Who needed Truman Capote and the Rolling Stones anyway?