A snapshot of Chris Whitley performing at a poky club in downtown Manhattan. He’s wearing the exact same clothes as earlier that afternoon when I’d interviewed him at a Greenwich Village coffee shop: white singlet, skin-tight jeans and tatty sneakers. He’d seemed to me a gentle, fragile soul, soft-spoken but also jittery and intense, chugging espressos and chain-soaking Marlboros. He was as wired on stage, but commanding too, holding the small audience transfixed, among them Bono and The Edge who had interrupted a recording session for the show. As his two-piece band laid down a taut rhythm, Whitley wrung hellfire out of a battered Dobro guitar, his voice weeping over the tumult. Right then he sounded like nothing so much as a doomed angel.

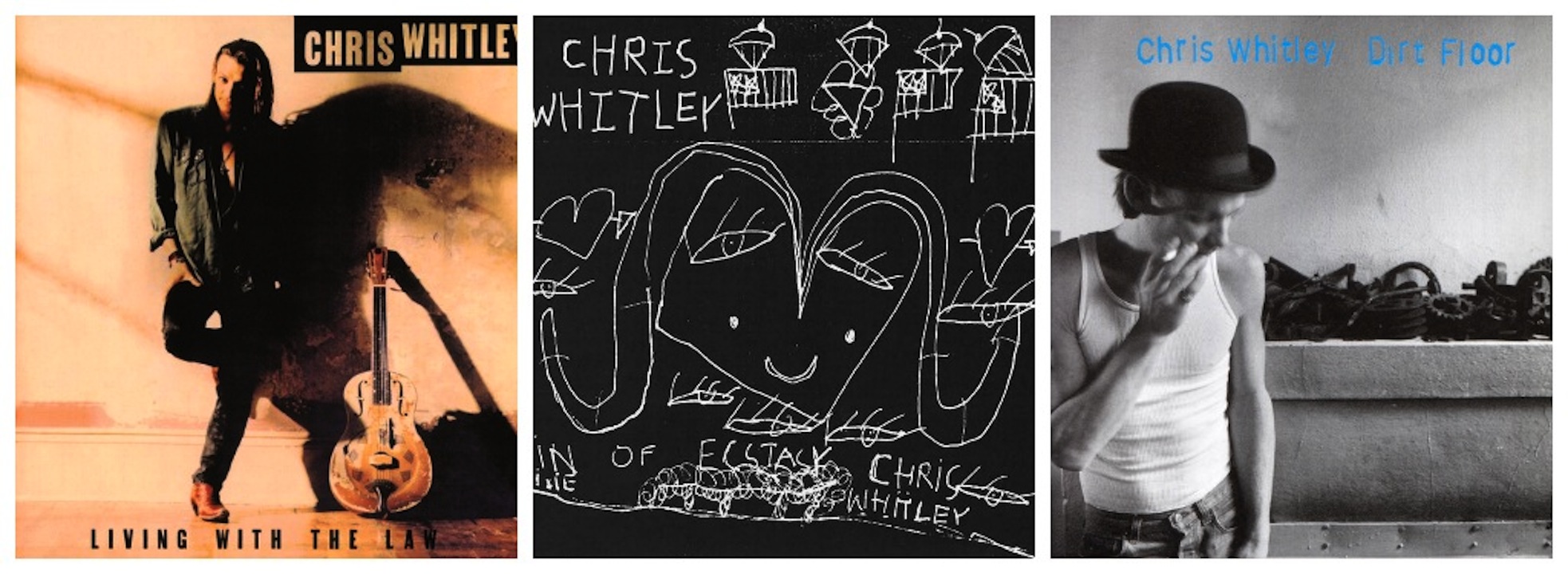

This was spring 1995 and Chris Whitley was preparing to release his second album, Din Of Ecstasy. Its predecessor, Living With The Law, emerged to great fanfare in 1991. A lush, modern blues confection, it was declared by Rolling Stone as Best Debut of that year, and Whitley was momentarily perceived to be the heir to Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen, labelmates of his at Columbia Records. He toured with Dylan and another heartland American troubadour, Tom Petty, but didn’t attract a mainstream audience. Back then the blues barely registered on the pop culture radar. And besides, Whitley was too conflicted, too complicated an artist to court mass appeal.

Against this backdrop and with his marriage crumbling, he returned to his adopted home town of New York to make Din Of Ecstasy. The result was an altogether different beast. Dismantling his debut’s trad-blues foundation, Whitley erected instead an edifice comprised of jagged edges and sharp corners. It was harsh and noisy, but also bold and occasionally brilliant. And it was a career killer so far as Whitley being a major-label artist was concerned, baffling executives at Columbia and shunned by the general public.

Fast-forward 10 years and Whitley was again holed up in New York, on this occasion in a cramped apartment strewn with the detritus of a vagrant musician – guitars, empty bottles, overflowing ashtrays. He’d spent the previous three years living with his German girlfriend, Susann Buerger, in the old East German city of Dresden. During the decade since Din Of Ecstasy he’d made a run of striking records on which he’d pushed his blues to almost avant-garde extremes, working from the margins. He’d returned to the US for a low-key tour, but at the end of it he found himself penniless and marooned.

One summer afternoon Whitley hosted an aspirant filmmaker, Jonathan Mayor, giving him what would be his last interview. On a hand-held camera, Mayor caught Whitley in the act of baring his soul. He was filmed perched on a mattress on the bare-wood floor of his single room. Years of toil in the outlands of the music, business as well as his ruinous excesses, had taken their toll. He’d always been thin, but now appeared emaciated. There were dark hollows under his prominent cheekbones, darker depths to his eyes, which stared down Mayor’s lens, desperate looking but also defiant, as if battling the dying of the light.

“He was very depressed,” Mayor recalls now. “At the same time, there were these sides to Chris that endured – an immense kind of potential to see beauty in art and the future. As bad as things had got, his creativity endured and so did his fighting spirit. It was a tough situation. He was drinking heavily and didn’t have a lot of options. He felt as if he’d tried really hard to be very good at something and sacrificed a lot for that. I don’t think he ever made music to be financially successful, but he felt betrayed, not by anyone in particular but by a world where that could be a reality.”

The surviving footage shows Whitley chain-smoking and gulping cheap wine from the bottle. His voice slurs, and now and then he’s racked by a hacking cough. At one point he looks into the camera, blinks back the memory of some torment or other and intones: “I’m just a motherfucker who’s fucking sick of thinking too much.” Three months later he was dead.

Christopher Becker Whitley was born on August 31, 1960 in Houston, Texas. His father was a high-flying art director for corporate advertising agencies. His mother was an artist, but faced a life-long struggle to make money as a sculptor and painter. The Whitleys had two more children: a son, Dan, three years Chris’s junior, and a daughter named Bridget.

As high-school sweethearts Whitley’s parents had snuck into local bars to see visiting bluesmen such as John Lee Hooker, and they filled their family home with music; the radio was most often tuned to a blues station broadcasting from the Tex-Mex border. From it and his parents’ record collection, Whitley picked up on blues greats such as Hooker, Muddy Waters and Bukka White, and contemporary bands including Cream, Led Zeppelin and local heroes ZZ Top.

“Chris and me would make our own fake instruments and put on shows for our folks,” Dan Whitley says today. “He had a makeshift guitar and I had drums made out of paint cans. I put rocks in them so they’d rattle like a snare.”

In 1971 the Whitleys upped sticks and relocated north to Connecticut. However, the move didn’t repair the serious cracks in their marriage and later that year the couple separated. Throughout the rest of his childhood, Whitley and his siblings lived a peripatetic life with their mother, drifting from place to place, shacking up in two-bit houses and on hippie communes in Mexico, Oklahoma and Vermont. The scars left by this rootless existence stayed with Whitley his whole life. It was in Vermont that he first picked up a guitar, and taught himself to play by ear.

“Originally he played electric,” says Dan Whitley. “He was sixteen when he did his first gig at a kids’ dance. There were so few places to play in Vermont, it was mostly bars and covers acts. Chris had some bad experiences. He was doing Cream and Johnny Winter covers and it didn’t go over well. It made him go acoustic, because the electric thing just turned people off.”

At 17 Whitley fled to New York and took a job in a Greenwich Village deli. Soon he was busking for chump change in Washington Square. By his own account he spent the next four years rattling around the city’s bars and coffee houses, renting a closet-sized room at an American Legion Hall for 130 dollars a month. Bizarrely, he had a chance meeting with a visiting Belgian travel agent called Dirk Vandewiele, who gave him a free plane ticket to Brussels and hooked him up with a local promoter.

He flew to the Belgian capital in July 1981 and spent the best part of the next decade in that country. While living in Ghent he formed an esoteric pop band, A Noh Rodeo, with his then girlfriend, Helene Gevaert, and her elder brother, Alan. The trio had a couple of regional hits before splitting in 1988, by which time Whitley and Gevaert were married and raising a daughter, Trixie. At the end of the 80s Whitley moved back to New York with his new family and got a job in a picture-framing factory. He returned to the city’s club circuit and began writing songs.

“I was working in a factory in my late twenties and my marriage was breaking up,” he once reflected. “But desperation can be a good impetus.”

A tape of Whitley’s songs found its way to producer Daniel Lanois, then riding a hot streak from his work on U2’s The Joshua Tree. Lanois arranged for him to go to New Orleans to record at his studio in the French Quarter with the in-house engineer, Malcolm Burn. This session produced such wide-screen songs as Big Sky Country, and led to a deal with Columbia and his debut album.

“He was somebody who was obviously inspired by the blues as a basic form, but not interested in just rehashing something,” says Burn. “He’d invented his own language and wasn’t playing by other people’s rules.”

Subsequently, Whitley’s wild spirit, and a deep-rooted sense of insecurity, led him to dismiss his first album as too polished, and he resolved to cut against the grain in future. There were other storm clouds on the horizon: the ending of his marriage, and a growing reliance on booze to combat his doubts and fears. Din Of Ecstasy came and went, as did a third album, Terra Incognita, after which Columbia dropped him.

Whitley sought solace at his father’s house in Vermont. The two men had a distant, fractious relationship, but during two days of recording in his dad’s barn Whitley poured his heart and soul onto a vintage reel-to-reel tape recorder and into perhaps his most deeply affecting record, Dirt Floor. Released in 1998 on tiny indie label Messenger Records, it showcased the essence of his undiluted talent across nine acoustic tracks that crackled like a naked bulb.

Dirt Floor began the second cycle of Whitley’s career. It was characterised by a series of starkly beautiful records, each a form of personal exorcism, and at the same time by the shrinking of his audience. It was as if the more he gave of himself, the less he was able to draw people in. Or as his daughter Trixie later told Jonathan Mayor: “The crowds got smaller and the clubs got shittier.”

“Chris was never at peace,” says Dan Whitley. “It was kind of what drove him – to find nirvana writing about his demons. But he was on a treadmill that he couldn’t get off. He had bills to pay, you know.”

“I went through a few nights with him that I won’t forget in a hurry,” says Australian blues guitarist Jeff Lang, who met Whitley at a gig in Melbourne in 1993 and remained close. “It’s hard to watch a friend face down their demons in front of you and come off second best.”

Susan Buerger first saw Whitley perform in the old West Germany in 1999. She wasn’t drawn to his music, but was captivated instead by the intensity he brought to it. At the beginning of 2001 she began promoting gigs at a club in her native Dresden and booked him to play. Such as it was, the show was a disaster; he turned up too drunk to play.

“He just lay there on the floor like a bug,” she says. “So I was immediately introduced to his issues. I thought he was a lot of trouble, and yet we fell madly in love that first night. I knew he wasn’t the perfect guy, but also that he was my soul mate.”

Six months later Whitley left New York and went to live with Buerger, who was 17 years younger than him, and her baby daughter. He settled in their home. Near the end of the Second World War Dresden was razed by an Allied bombing onslaught, and subsequently rebuilt from the ground up. It was as if the city was now able to restore Whitley’s wrecked psyche, and he made two extraordinary records there: 2003’s Hotel Vast Horizon and the following year’s War Crime Blues, both of them hushed and haunting.

During this period Buerger shot a series of intimate black-and-white portraits of Whitley on a camera he’d bought for her. Literally and figuratively, he is naked before her lens. In these pictures there’s a sense of him being at ease, but then again a spooked quality residing in the black pit of his stare.

“Most of the time here he was sober,” she says. “He liked this kind of family life and having a home and roots. I went out to work, and he cleaned the house and did the cooking. But he had such a hard time leaving for a tour. He’d get fucked up at the airport. He told me he felt scared to go.”

In 2004 Whitley lost his mother, and her death hit him hard. Toughest of all was the fact of her dying alone and in poverty, her devotion to her art having brought her neither material comfort nor salvation. The parallels would have been obvious to him, and he threw himself into his music as if a hellhound was on his trail.

He went to Australia to make the Dislocation Blues album with Jeff Lang, released posthumously in 2007, and to New York to repair old wounds with Malcolm Burn on Soft Dangerous Shores. Both men saw first-hand how drink and his devils had ravaged Whitley. In Melbourne he went on a three-day bender before recording. He was calmer when Burn encountered him, but weaker too. “I knew something was up as soon I saw him,” says Burn. “He’d lost a ton of weight, and had these intense coughing fits where we’d have to take a break. Yet he was still just as devoted to his craft, if not more so.”

In Spring 2005 Whitley was offered a US club tour. He took it, against the counselling of friends worried by his declining health and despite the small amount of money it would bring him. He had his reasons for going; his relationship with Buerger was floundering on the rocks of his boozing.

Back in New York Whitley cut what would be his final record, Reiter In, during a drunken three-day session and with a pick-up band. It was released out after his death, and sounded splenetic and harrowing. At the time of making it he was facing eviction from his apartment.

“I was worn out by all his booze shit,” Buerger admits. “One day he called me from New York to tell me this guy Jon Mayor was filming him right there and then. I was outraged, and wanted to know what he was doing letting someone in while he was fucking up. Later on, when I saw the material, I realised that Chris had really wanted to get something across, like he’d foreseen something.

“He had such a hard time making compromises and he paid the ultimate price for it. In German we have a saying that you can be tired of life. And at the end he was like that, tired of living.”

At this, his lowest point, Whitley accepted an entreaty from his brother Dan to go and rest up at the ranch house of an old family friend in Houston. Once back in Texas he began experiencing chronic pains in his right leg. He’d had a long-standing aversion to doctors, but was persuaded to go for a check-up. He was subsequently diagnosed with terminal lung cancer. Buerger flew from Dresden to Houston to join Whitley’s family at his side.

“He looked like a dying man,” she remembers. “Within a couple of days he decided to leave hospital and go back to the ranch, which he hated; he didn’t want people thinking he’d returned home to die. During those last weeks he was fighting through all these situations where he’d fucked up or felt humiliated. Some of them happened thirty years ago, but Chris could not let them go. He also had this typical son thing of hating his father for certain things, but really just wanting a hug from him. His dad never gave him that, not even on his deathbed.”

Chris Whitley died at 4pm on Sunday, November 20, 2005. He was 45 years old. Both his brother and Buerger believe that at the end he was at last at peace.

“I was alone with him in his room,” Buerger recounts. “I held him, lay on his chest and told him how much I loved him. He always used to say to me: ‘Have a safe trip,’ even if I was just going to drop my child at kindergarten. So that’s what I said to him: ‘Have a safe trip.’ He exhaled, and that was it. It was just a breath and it was beautiful.”

In the years since his passing, life has rolled on for those who knew and loved Chris Whitley. Trixie Whitley sings with Daniel Lanois’s band. In 2014 Dan Whitley made his first record, at the age of 51 and with Malcolm Burn producing. Jonathan Mayor is currently entering the Whitley documentary Dust Radio into film festivals and seeking a distributor.

Susann Buerger returned to Dresden and now works as a photographer. In accordance with Whitley’s wishes, she took his ashes to scatter at various sites that had meaning to him. She intends to make her final pilgrimage on the anniversary of his death this year and will let the last of him go into the River Elbe.

Whitley’s legacy remains etched into the records he made. They are the bruised works of a gifted musician who simply hurt too much.

“When he felt safe and loved he had a lot of beauty and joy,” Buerger insists. “But he was also a very doubting person, and most of all of himself. That was painful to watch. He used to tell me that he was a piece of shit and that sooner or later I’d leave him. I was twenty-eight when he died, and I wish I’d been more mature and able to convince him to stop hating himself. On the other hand, I saw a different person at the end, someone who was not afraid any more.”