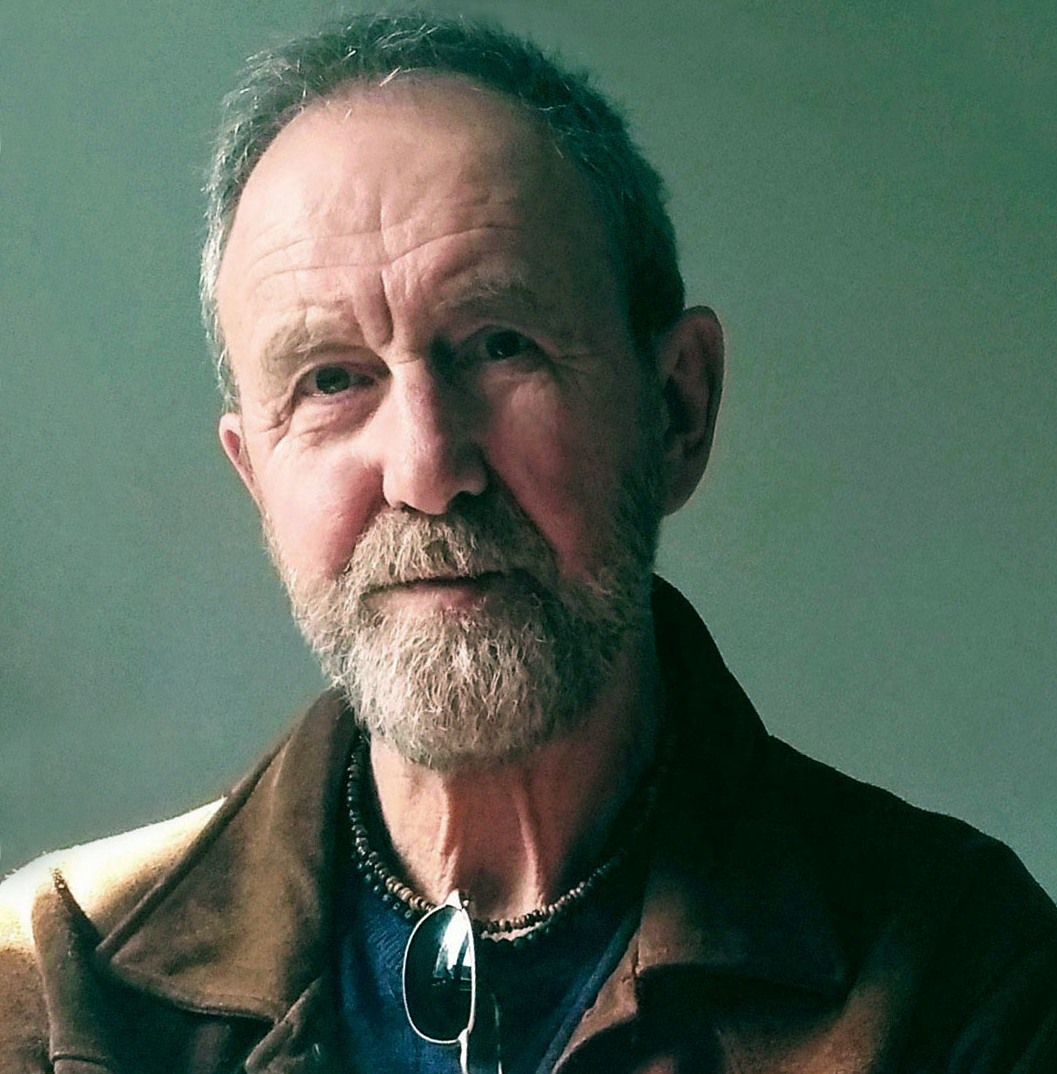

“A lot of early Genesis and Roxy Music comes from Family… I think we set a certain kind of style for the next generation”: Roger Chapman recalls Music In A Doll’s House

With its twisted arrangements and otherworldly vocals, Family’s mind-boggling 1968 debut set a benchmark in underground music

Post-war, pre-AIDS and in the middle of a sexual and music revolution, the late 60s was a time when people were jumping into bed with whoever they felt like at the drop of a hat. Among the one-night stands, some unlikely relationships were being formed. Such as the one in 1968 when Reprise, the woefully unhip US record label founded by Frank Sinatra and with a roster headed by him and sharp-suited rat-pack crooners Dean Martin and Sammy Davis Jr, hooked up with a bunch of dope-smoking, loud music-loving lads from Leicester. It was an odd coupling. But the first date between Reprise and the band Family resulted in something truly special, as vocalist Roger Chapman told Prog in 2012.

By 1968 Family had made a name for themselves on the gig circuit and as a festival favourite thanks to their attention-grabbing, highly individual rhythmic fusion of R&B, soul and envelope-pushing progressive rock. Their dynamic live performances usually saw the manic Roger Chapman reduce several tambourines to matchwood and twisted metal as he battered them against his mic stand.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic, executives at the mighty Warner Brothers-owned Reprise were looking to tap into something new. They already had the megastar that was Sinatra. But they’d watched British pop music invade the US and The Beatles go global, and they wanted a piece of the action. Reprise had dipped a toe in the safer end of the rock market by signing Neil Young and Joni Mitchell. Now they were looking to sign a hip new British band.

“I don’t really know the main reasons why Reprise signed Family,” says Chapman, more than 40 years later. “But they wanted to break into the English market and the rock market and start in the right direction. I have to say, at the time, we were a very, very hip band. And quite big. We’d made a big following on the road, we did loads of festivals. We had a hell of a lot of respect and we were branded as a serious, class act. Reprise thought we would help them to get a foothold in the UK.”

In spring 1968 Family began sessions for what would become their first album, working in Olympic Studios at 117 Church Road, Barnes, south-west London, pouring their ideas into the same four-track mixing desk used on albums and singles by heavyweights such as Jimi Hendrix, The Rolling Stones, The Yardbirds and the Small Faces. “We had quite a lot of the songs written,” Chapman recalls, “and there were some that were written in the studio as we went along – at least arrangement-wise. Being the era it was, invention was the thing without even thinking about it, and you were bouncing things off walls. We were using violin, soprano sax... So you just twist things around.

“And I assume there were a few drugs involved as well. Family wasn’t a druggy group, as such, but half the band would have been smoking dope – that’s what it was in those days. Psychedelics? Not very much – just for the weird bits.” Recording began with Jimmy Miller producing, and Eddie Kramer and George Chkiantz engineering. Miller was taken off the project when The Rolling Stones asked him to work on their next record (which would become 1968’s Beggars Banquet). Family must have cursed their luck. But it may well have been a blessing in disguise.

Exit Miller; enter Traffic guitarist Dave Mason. Along with Mason came production and arrangement ideas that played a big part in making Family’s debut record a great psychedelic progressive rock album – arguably the first progressive rock album – and a genre classic.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Released on July 19, 1968, Music In A Doll’s House met with critical acclaim, including crucial support from BBC DJ John Peel. It sold well in Europe, but less well in the then prog desert of the US. In the UK it eventually reached a creditable Number 35; quite a feat for such a radical, experimental and adventurous record, in the era of Number One artists such as Andy Williams, Scott Walker, The Four Tops, The Seekers and Tom Jones.

With 13 tracks proper, plus three short Variation On A Theme Of... interludes linking some of the pieces, Music In A Doll’s House was a revelation. Here was music painted on a big canvas with a broad palette of colours. Trad jazz saxophonist Tubby Hayes lent horn arrangements to Old Songs New Songs, while wonderfully-wrought tracks such as the gently lilting Mellowing Grey, the hypnotic The Breeze, the darkly eerie The Chase, the rocked up Hey Mr Policeman and the acid-flavoured Never Like This came from a more familiar place – blending elements of rock, R&B, soul, jazz, psychedelia, blues and pop.

What truly cements Music In A Doll’s House’s formidable reputation as one of the great progressive albums are its four remarkable cornerstone tracks: Me My Friend, See Through Windows, Peace Of Mind and Voyage. These tracks featured strange, dark new sounds including backwards instruments, cascading Mellotron, eerie echoing violin, trumpet, saxophone, studio effects and, not least, Chapman’s bleating, almost impossibly severe vocal vibrato. At times you were convinced that the Tardis had come screaming in and landed in your front room – in glorious stereo. It was fabulous, ground-breaking stuff.

In mid-’68, progressive rock (or ‘underground’ music, as it was called back then) was still in short trousers and smoking behind the bike sheds. King Crimson’s startling In The Court Of The Crimson King debut album was still a year away; Yes had only just changed their name from Mabel Greer’s Toyshop and started playing gigs; Genesis were barely out of school and recording their first album with producer Jonathan King; and Jethro Tull were still a blues band just about to release their first record. ‘Progressive’ rock back then was bands such as Traffic, The Moody Blues, Pink Floyd, The Nice, Barclay James Harvest and The Mothers Of Invention, setting out their stalls with the kind of music people had never heard before.

Family were as apart and as unique as any of those. While Music In A Doll’s House didn’t sound like anything else, wanting to throw down a radical new marker wasn’t on the band’s agenda, according to Chapman. “Not at all,” he says. “That’s just what Family was at that time. And, again, the ideas were coming in while we were in the studio. While we were there, the idea came to use different versions of the songs and use them as links. I think the idea was John Gilbert’s, our manager’s. I forget, but it was over 40 years ago.”

Music In A Doll’s House was a one-off for Family. The follow-up, 1969’s Family Entertainment, was a very different and different- sounding album. It was more song- focused and had less of the debut record’s arrangements, which had proved impossible to reproduce live. This time, says Chapman, the band made a conscious effort to set it apart.

“The difference was, I think, John [Gilbert] realised that with Music In A Doll’s House we’d made an album that was almost too eclectic, and almost couldn’t be reproduced, and decided we should go a bit more down the road of music we could play on stage. We also used a different producer, Glyn Johns. Again, we already had quite a lot of the songs for Family Entertainment, and with the arrangements we were playing on stage – songs like Weaver’s Answer, How-Hi-The-Li, Second Generation Woman.”

Next came 1970’s wonderful A Song For Me, an album that includes some of Family’s best songs, such as Drowned In Wine and Love Is A Sleeper, and was the other book-end of Family’s three-album purple patch. The band recorded four more studio albums – Anyway (part live), Fearless, Bandstand and It’s Only A Movie – before calling it a day after their final concert at Leicester Polytechnic on October 13, 1973.

All of those albums had their merits, yet none of them captured the essence of Family as well as those first three, and each was less prog and more mainstream than the one before it. On the plus side, depending on your point of view, that change brought chart success, with their best-known song, the seemingly evergreen hit Burlesque reaching Number 13 in late 1972. Yet it’s perhaps no surprise that for prog aficionados Music In A Doll’s House is Family’s defining record.

“I think it was a very good representation of the time,” agrees Chapman. “I still think a lot of the songs still stand up, and as album I think it stands up well among anything that we made. One of the good things about Family was that there were no two albums alike, so they’re really difficult to class against each other.

“But, obviously, some were better, because of the song structures and the songs themselves. I wouldn’t say Music In A Doll’s House has got all the best songs on it, but it does have a classic piece of production of the times.”

While Genesis’s influence on Marillion is plain for all to see, as is Pink Floyd’s on, say, Crippled Black Phoenix, at first glance it’s harder to see which rock bands were directly influenced by Family and Music In A Doll’s House. Some of Queen’s future members, especially drummer Roger Taylor, were big fans of the album while sharing West London student digs in ’68 and ’69, but Chapman claims Family have other famous fans.

“A lot of early Genesis comes from Family,” he insists. “Them and Roxy Music, in my mind. In the same way that Cream were the stereotype/template for all the multi-millionaire three-pieces that came after them, I think we set a certain kind of style for the next generation.”

Perhaps the most important influence Music In A Doll’s House had on what came afterwards is that it opened people’s minds and broadened their horizons regarding what was possible to those with imagination and a determined spirit; to those who, to coin a phrase, prepared to boldly go where no band had gone before. Thankfully, many went on to do just that – warp factor five, and don’t spare the engines...

Classic Rock’s production editor for the past 22 years, ‘resting’ bass player Paul has been writing for magazines and newspapers, mainly about music, since the mid-80s, contributing to titles including Q, The Times, Music Week, Prog, Billboard, Metal Hammer, Kerrang! and International Musician. He has also written questions for several BBC TV quiz shows. Of the many people he’s interviewed, his favourite interviewee is former Led Zep manager Peter Grant. If you ever want to talk the night away about Ginger Baker, in particular the sound of his drums (“That fourteen-inch Leedy snare, man!”, etc, etc), he’s your man.