When Fanny formed in 1969, the music world was an entirely different place. No one believed that four women could possibly be skilled songwriters and musicians, much less be able to rock with the commitment and ferocity of their male counterparts. Fanny could do it all – and spent their entire career battling to win over the cynics and non-believers. “Kim Fowley came into our dressing room at the Whisky A Go Go,” recalls Fanny guitarist June Millington. “He said, like he’d just had this bright idea: ‘I’m going to form a band like yours but we’re going to make money.’ And that last part was what would make the difference. Because Fanny was working real hard but we weren’t making very much money. I went kind of quiet for a second, because I do think about things, then I turned to him and said: ‘Why not?’ That was my assessment. Why not? We knew we were opening the doors for other female bands, only now it was a guy who was going to take advantage of it. But you know what? He did it. They did it.” True to his word, Fowley hit pay dirt with his jailbait fantasy The Runaways. Meanwhile, Fanny – the first all-girl rock band to release an album on a major record label – faded into bitter obscurity. Is there much about them in the history books? Sweet FA. It was an unseemly, uncalled-for fate for the pioneering Queens Of Noise.

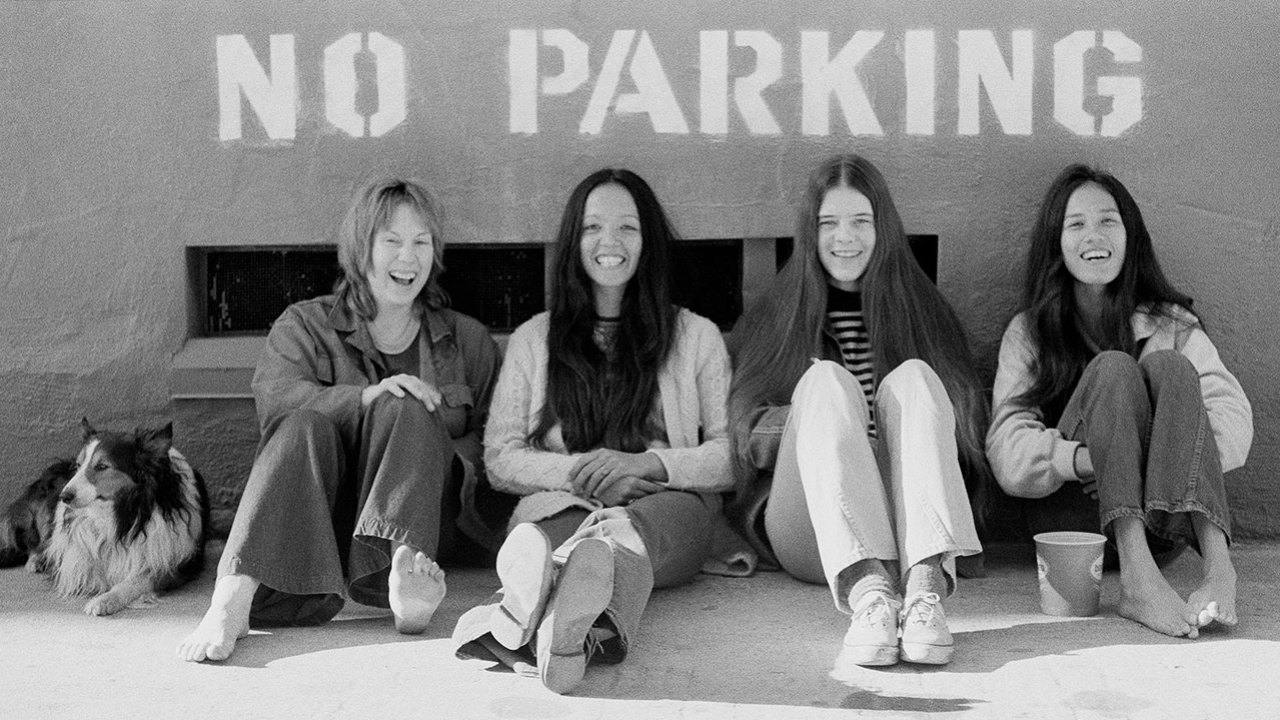

Fanny’s roots go back to the beginning of the 1960s, when sisters June and Jean Millington moved with their family from the Philippines to Sacramento, California. Their father served in the US Navy and met their mother just after World War II. They married in Manila in ’47. Being both biracial and bicultural, the girls found it hard to integrate Stateside, so they turned to music both as a release and in an attempt to make new friends. In ’65 they formed their first band, The Svelts, with June on guitar and Jean on bass. The line-up would also feature two other future Fanny members: Brie Brandt and Alice de Buhr. The former was The Svelts’ original drummer; the latter her replacement.

“We played a lot of Motown,” de Buhr says of The Svelts. “The solid rhythm foundation in all of those great old Motown songs, with those wonderful beats, really helped us click in and find our groove.”

De Buhr left to form another all-female group, Wild Honey, while June and Jean continued with The Svelts. “But neither of us was finding any great success or having a whole lot of fun,” she says. “So we decided, y’know, let’s get over the petty differences and get the band back together. So that’s what we did, but we kept the name Wild Honey instead of The Svelts. We thought: ‘Hey, let’s go to LA and try to make it, get a record contract. And if we don’t, we’ll all come back and go to school. We’ll give it all up.’”

In fact, Wild Honey were on the verge of doing precisely that – splitting up – when they were talent-spotted at the Troubadour by the secretary of record producer Richard Perry. They snaffled a deal with Warner Brothers offshoot Reprise on the strength of a 15-minute audition for Perry at Hollywood’s Wally Heider studios, home to the likes of Jefferson Airplane and Neil Young. “What did Richard see in us?” asks de Buhr. “He saw a bunch of good-looking girls rocking their asses off and he said: ‘This is a band that needs to be recorded.’”

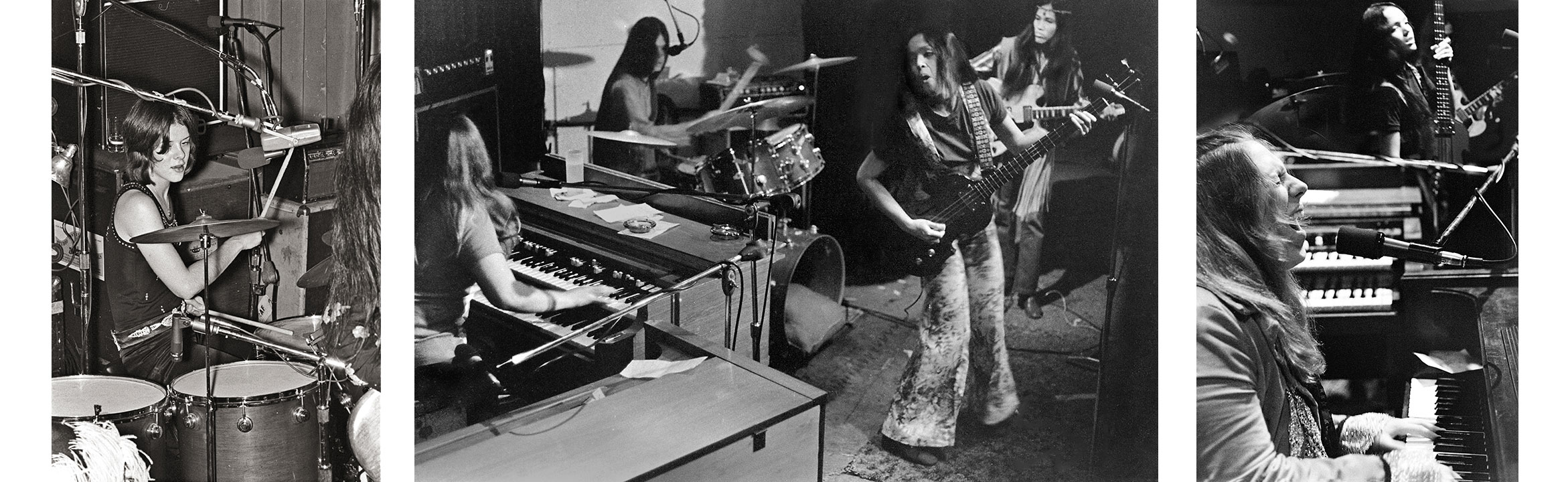

“Women who could rock hard were a rarity in those days,” says Jean Millington. “Most of the girl bands were novelty acts. When we were sixteen, seventeen years old and playing up in Reno, there was a band called Eight Of A Kind – four females who performed topless, you know what I mean? That’s what we were up against. They were radically different times. We had to prove that we were serious and that we could really play our instruments.”

“There were all-girl bands before us,” concedes de Buhr, “but there was no other all-girl band that had been signed to a major label to release full albums. Goldie And The Gingerbreads, Isis and the Pleasure Seekers were around but they were only putting out singles.”

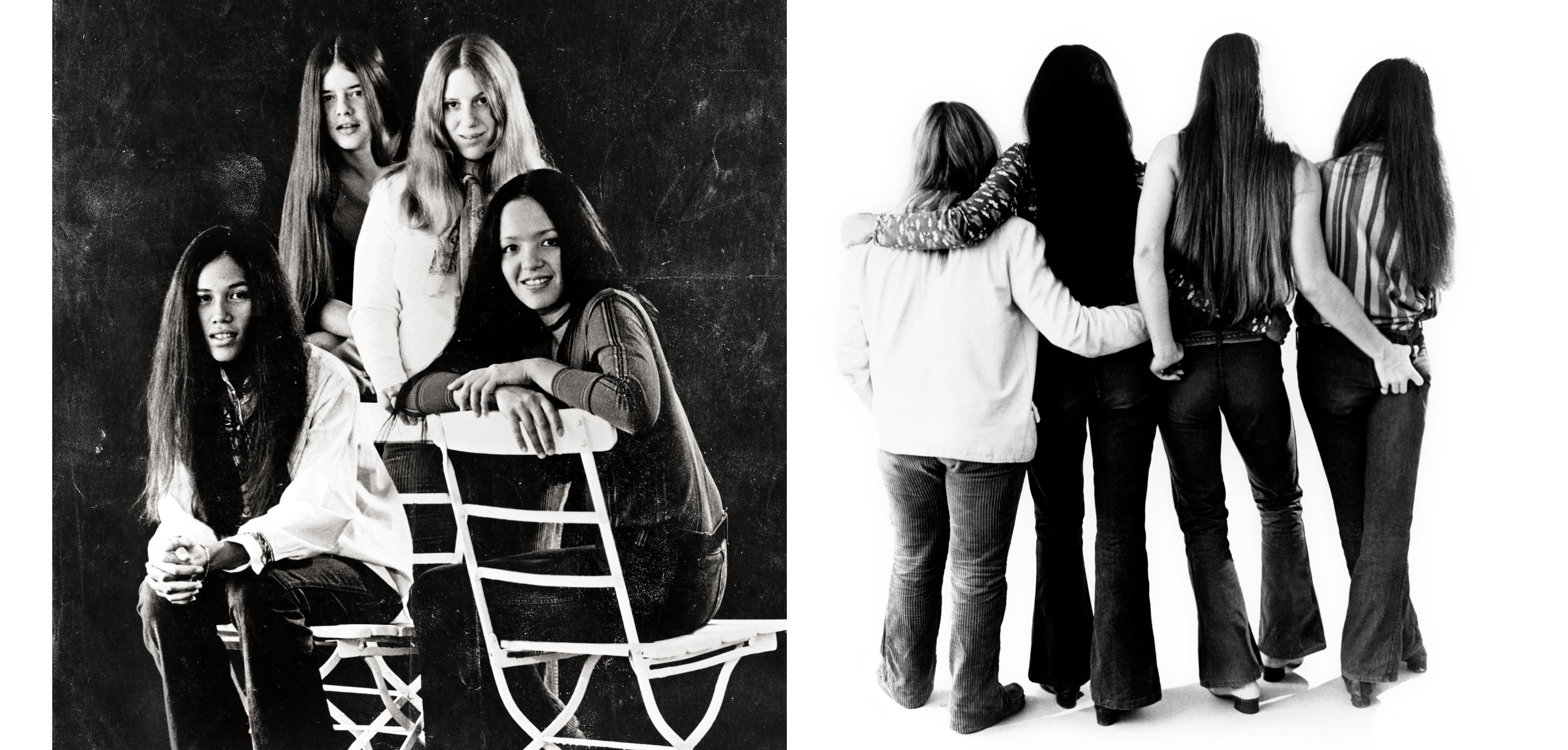

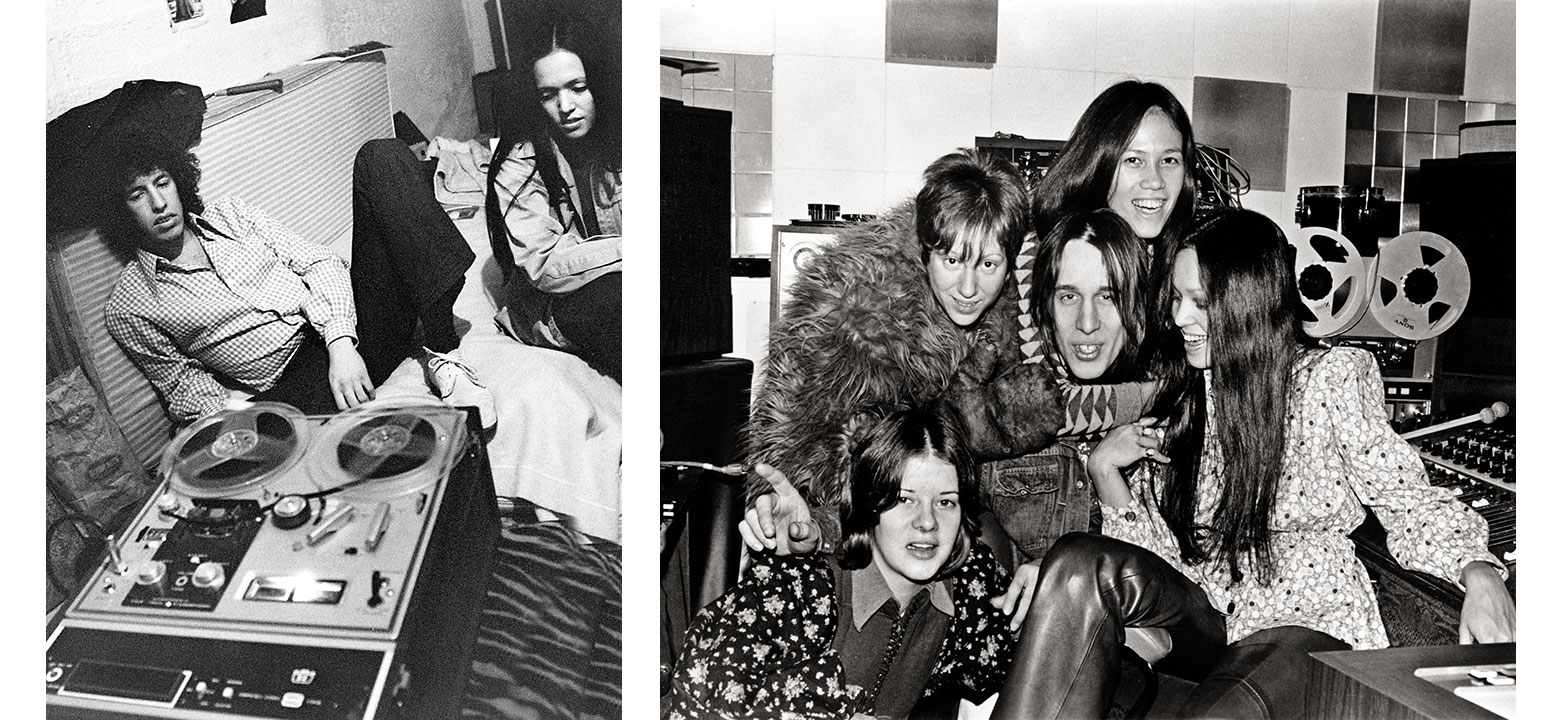

In 1970, the band that would become Fanny – completed by keyboardist Nickey Barclay – entered the studio to record their debut album, with Perry producing. Perry – who the following year would mastermind Barbra Streisand’s breakthrough album, Stoney End, which also featured June Millington on guitar – had a light touch that didn’t bring out the best in the girls. But the synergy between band and producer improved on subsequent releases.

“Richard was very patient with us,” says de Buhr. “I don’t think we felt any pressure from Richard, although we felt pressured by ourselves.”

There was a another pressing matter to consider: a new name for the band. June mentioned that she had heard of another female group called Daisy Chain. “I loved that there was a girl’s name in it and we all started trying to think of something similar,” she says now. “Someone called out ‘Fanny’ and it got added to a list of wild, zany, far-out, psychedelic sixties names. A few days later I found out that our manager and producer liked that name too. And just like that we had the name of our band: Fanny.”

“We weren’t aware of the different connotations until we went over to play in Europe,” de Buhr says, chuckling. “That’s when everybody started saying: ‘Well, you know… ha-ha-ha, titter-titter.’ We said: ‘Well, sorry, that’s our name. It’s a woman’s name, it’s got nothing to do with that part of the body. So get over it, you pricks!’”

Even so, the band’s record company wasn’t averse to the occasional double entendre, Fanny being slang for ‘backside’ in their US homeland. Cue a marketing campaign that urged people to ‘Get Behind Fanny’…

Fanny were determined to level the male-dominated playing field. In June Millington they had a bona fide guitar heroine, someone who could crank it hard, heavy and with feeling. “Lowell George, Elliott Randall, Jeff ‘Skunk’ Baxter… these guys took me as an equal and didn’t sneer at me,” she says. “After a certain amount of time I knew I was as good as them – or better. So don’t mess around with me. I still have that attitude.”

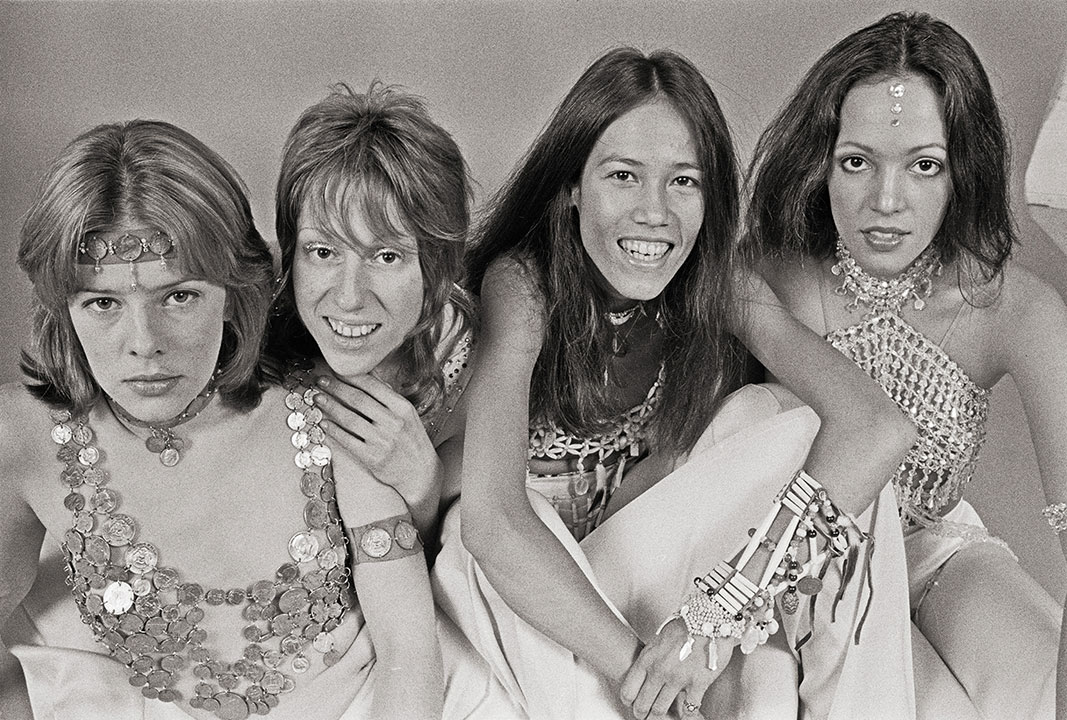

Bassist Jean provided a sultry counterpart to her wild-eyed sister, and her partnership with drummer Alice de Buhr was intuitive and rock-solid. Nickey Barclay, meanwhile, was in many ways Fanny’s secret weapon. Her classy keyboard skills were well-renowned: before committing full-time to the band she had been a member of Joe Cocker’s Mad Dogs & Englishmen touring ensemble. As a bonus, all four of Fanny were excellent singers, with Barclay’s soulful voice just edging it.

Despite their musical prowess, Fanny found it hard to win over audiences. “There was a whole lot of curiosity about us,” says Jean, “which was good to draw in the crowds, but it was somewhat difficult for the first ten minutes or so of a show until people figured out we actually could play. We were such an anomaly – no one expected women who could rock that hard. I still think women are proving themselves nowadays. I even find myself being somewhat prejudiced in that way. When a girl group comes up, I always ask myself: ‘How well do they actually play?’ I mean, hats off to The Go-Go’s, they were very successful, but as far as I was concerned, they were adequate musicians.”

“When we toured in Europe, the audience reaction was much more positive than it was in the States,” reveals de Buhr. “I particularly loved playing in England, where the fans never looked at us as a gimmick.”

Unusually for a US band of the early 1970s, Fanny visited Europe regularly, both as a headline act and opening for the likes of Slade, Jethro Tull and Humble Pie. “People over there got it,” says June. “I wish we’d moved to Europe and just kept playing and recording there. We were trying to play intelligent rock. If you look at our lyrics, they’re not [Runaways song] Cherry Bomb. We were serious about being musicians and songwriters. We wanted to be the smart chicks who could play.”

Fanny released four albums for the Reprise label: 1970’s self-titled debut, the following year’s Charity Ball, 1972’s Fanny Hill (recorded at Apple Studios in London) and their finest and most sonically satisfying, 1973’s Todd Rundgren-produced Mother’s Pride.

“We progressed with each successive record,” says de Buhr. “Sometimes I cringe when I hear something on the first album and the drum is rushing the beat. Oh hell, c’mon! But I am proud of Fanny’s body of work, most definitely.”

Fanny fought hard to be accepted as serious musicians. Yet there was a behind-the-scenes story that record company and management – intent on eroticising their charges – wanted to keep under wraps.

The sexual orientations within the band were complicated. Both June Millington and Alice de Buhr are gay; Jean Millington is straight; Nickey Barclay came out as bisexual shortly after she left the band. It was quite a melting pot.

“Oh, it was,” agrees de Buhr. “Back in the day, you couldn’t be gay. June had a big fear that if anybody found out we were gay, it would be the end of our careers.”

“I didn’t hide it; everybody knew. The record company just said not to talk about it,” counters June. “The fact I played lead guitar came ahead of any questions about sexual politics. I really didn’t think much about it at the time – we were just living our lives. And there was a lot of swapping and gender-bending and experimenting with free love and drugs in the late sixties and early seventies, you know? I’ve slept with both sexes. I’ve still got a photo of one of my boyfriends in seventy, seventy-one, who was black and I really liked him. So there it is, you know? Those kind of assumptions shouldn’t be made so casually because we were a part of those times.”

“A lot of what was difficult in the band dynamic was down to us being really young,” says Jean. “We had no one we could really talk to and there was a lot of internal pressure. We ended up having quite a few group-encounter sessions to try and work things out. There was just so much outside pressure to release albums, tour hard and put on great shows, it brought out the inherent insecurities within us.”

Even more of a pressure was the battle against being promoted as sex objects. “I remember doing a photo shoot in Germany, up in the mountains,” says June. “We were in front of a chalet and the photographer wanted us to get on our hands and knees, like submissive creatures. I turned to our road manager and said to him: ‘Do we have to do this? And he very quietly said: ‘Yes.’

“That was a big moment for me,” she continues. “I knew that we were being thrown to the dogs in that sense. It felt like all our hard work was being chucked away for this crap idea that girls couldn’t possibly be decent musicians. That contributed to pushing me over the edge.”

“There was a lot of pressure for us to glam it up,” says Jean. “Warner Brothers apparently thought it would help us sell more records. And that was a big bone of contention, especially for June.”

Ultimately, the pressure of being a trailblazing female rock guitarist proved too much. In 1973, June Millington had a nervous breakdown. “I couldn’t eat or sleep, my body just gave up,” she says. “People assumed it was down to drugs, but it wasn’t. All we did was rehearse or go on the road or record. I was just really tired and I snapped under the strain. It was very scary. I didn’t want to leave Jean. I didn’t want to leave the band after we’d worked so hard. It was a pretty terrible decision to make. But I just couldn’t continue. I was lost.”

“Once June quit, I really didn’t want to be in Fanny without her,” says de Buhr. “Patti Quatro [ex-the Pleasure Seekers and sister of Suzi] joined the line-up but she wasn’t June. Her guitar sound was different, she played different kinds of leads and it wasn’t interesting to me.”

With Brie Brandt (formely of The Svelts) replacing de Buhr on drums, Fanny left Reprise and signed to Casablanca, home of Kiss and Donna Summer. Their sole album for the label, Rock And Roll Survivors, produced an unlikely hit single in Butter Boy, written by Jean Millington about a brief fling with David Bowie. (“Was any butter employed? Er, no! It was au naturel, if you will.”) Jean sang on Bowie’s Fame and in 1978 married his guitarist, Earl Slick.

- AC/DC's Brian Johnson could perform live 'inside 6 months'

- Video: Mike Portnoy thrashes metal classics on a tiny Pokemon drum kit

- How Led Zeppelin III Was Their Most Misunderstood Album

- Alter Bridge’s Myles Kennedy – 10 Records That Changed My Life

In a 1999 interview with Rolling Stone, Bowie returned the compliment by saying: “One of the most important female bands in American rock has been buried without a trace. And that is Fanny. They were one of the finest rock bands of their time, in about 1973. They were extraordinary. It just wasn’t their time. Revivify Fanny. And I will feel that my work is done.”

So, was it a case of too much, too soon for Fanny? “I think it was too much, too soon for the general public,” replies June. “I mean, we were on all the rock shows, we were even on The Tonight Show, y’know, so that should’ve been enough. But, man, we just couldn’t crest the edge. Believe me, we worked so hard, we did so many interviews, we played so many gigs.”

Nickey Barclay doesn’t talk about Fanny any more. Interview requests fell on deaf ears. “After Fanny broke up, it seemed like Nickey couldn’t stand to be herself,” confides Jean. “For a while she played in England, then in Ireland, and she used to call herself Annie Laurie. That was her persona. Then she moved to Australia. And from what we know she is not in good health. But Nickey had a very hard time with her identity, so who knows what happened in the context of being raised in this dysfunctional family?”

“After I left the band I went to work for a record distributor in Los Angeles,” says de Buhr. “I remember hearing the guys in the promotion department saying Fanny was a joke. It broke my heart. So I didn’t used to tell people I was the drummer in Fanny. It’s only recently that I’ve come to realise that what we did was really important. I’m now in the process of helping Real Gone Music reissue all of our albums.”

“I’m still pretty impressed by what we did forty years ago,” says Jean. “As a matter of fact, when June and I get together for the occasional show, it comes right back. It’s unbelievable.”

June is now artistic director for the Institute for Musical Arts (IMA), a teaching, performing and recording organisation with a mission to support women in music and music-related businesses. She’s just completed her autobiography, Land Of A Thousand Bridges.

“To me, the name Fanny brought up a sweet aunt somewhere in the Midwest, or a favourite grandmother who fed you warm cookies,” June reflects today. “And it had an edge, too. Hey, this was rock’n’roll. We had to prove we could play like guys, and we couldn’t use a can opener to sway public opinion. We needed a buzzsaw. We didn’t want to just conquer the world, we wanted to be immortal.”