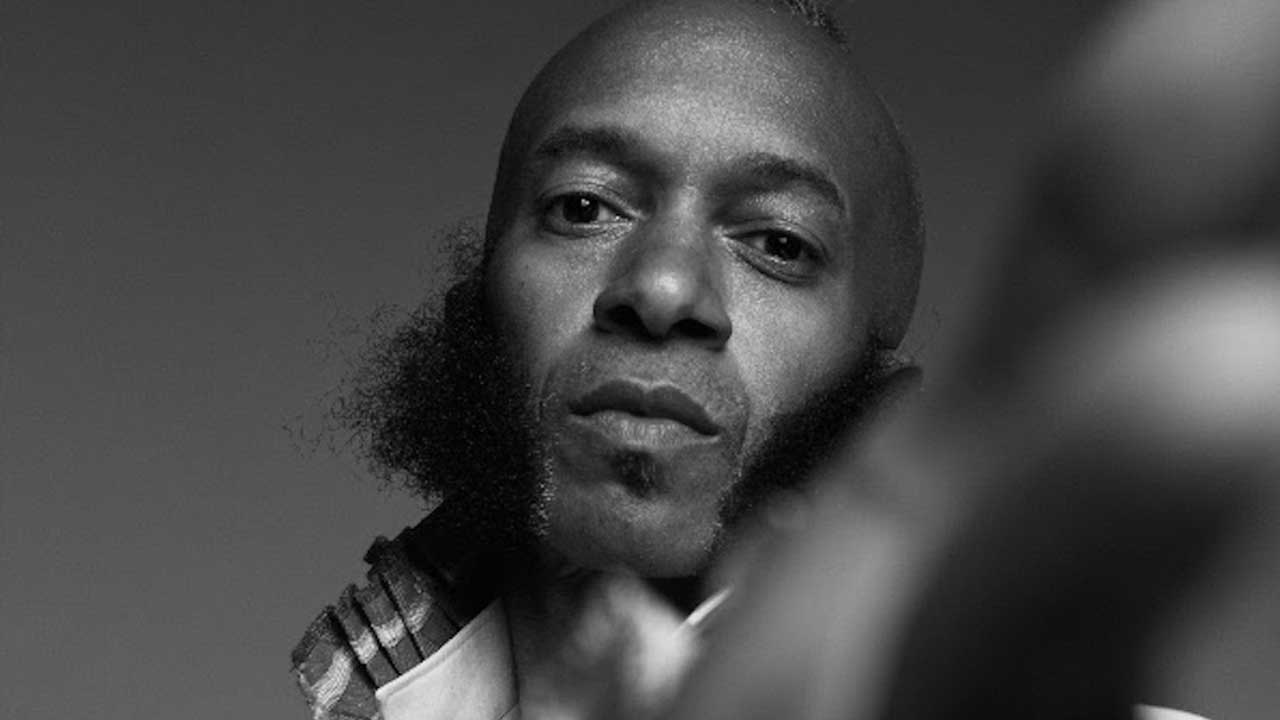

A moment of boredom and a visit to a genealogy website led to Fantastic Negrito, aka Xavier Amin Dphrepaulezz, discovering a secret family history packed with more peril, intrigue and romance than your average Hollywood film.

Not only did it turn out that his father had fabricated his entire past, but his eight-time grandparents were revealed to be an African slave and a Scottish servant who met and fell in love in Virginia 270 years ago – a time when interracial relationships were against the law. Because of their bravery and perseverance, the couple not only made it, their children were legally free, as were the generations that followed.

Their incredible story is the jumping-off point for the new album, White Jesus Black Problems, a searing mix of rock’n’roll and timeless R&B, which takes on themes of racism, capitalism and freedom in an all-too-modern context.

What was the starting point for White Jesus Black Problems?

“I was ready to make my fourth record, and I wanted to make a record with artists that I listened to as a teenager. I wrote down the list of a bunch of artists and the first guy I got was Sting. We got together, recorded a song, and it was a great start to an album of duets. Then the pandemic happened, and that dream was over, because you couldn’t hook up with people.

So I drifted back to the farm I live on. Eventually I got a call to do a TV show in Atlanta, which was great, because it was the first gig in a year. I’m stuck in this room [waiting to perform], And I start looking at messages from people and one was a link to ancestry.com. And as I pressed that link, my whole life changed.”

That was when you discovered your seven-times great-grandparents’ story?

“Well, first I found that everything about my father was completely fabricated. He lived this double life. I didn't even know his first name, his real last name, what country he was from. He had children before. So that was when the universe hit me with that title, White Jesus Black Problems.

My dad was born in 1905 – that's a generation after slavery. And he was always this progressive, smart guy. I thought, if you were black at that time in America, that's not a good thing, to be a person that's progressive and thinking outside of the box. I understood that. He wasn't going to cry about the injustice. He's going to do something about it. So he made up a lie.

And I thought that's White Jesus Black Problems. This is very good, Dad, to create all this. I mean, you've seen my last name, who comes up with that? So I was beside myself, I couldn't believe it. I had to call my mother, who's in her 80s, and give her the news.”

What happened when you looked deeper into your family history?

“I got really curious about all these well-dressed African Americans on my mother's side, and I'm looking at the year of the pictures. First, how do you get pictures if you're black and enslaved? Oh, this is photo day on the plantation? I don't think so. Then I discovered that they're free. Free? That's a strange word for us people that are from the South.

I started digging and it keeps going: fourth generation, free, fifth generation, free, sixth, free. Now for African Americans, we can only go to about the third generation or maybe fourth because of enslavement. I was having some kind of mental meltdown in the room because I couldn’t really accept that they’re free, in the South, and they're related to me. I almost felt like I cheated somehow, it was a very strange feeling. It wasn't all joy.”

How far back could you go?

“I kept going and in the place of the person that would be my seventh-generation grandmother there’s a document that says: ‘Elizabeth Gallimore presented in Amelia County Court, Virginia, for unlawfully cohabitating with a negro slave who belongs to Henry Jones, and having several mulatto children.’ That's the weirdest thing I could read. I kept retracing the steps, and it keeps going back to this document. And I thought, again, White Jesus Black Problems, but this time a white person is involved.

Here's a story about people on opposite sides of the spectrum, one from the UK, one's an African slave, but they got something done. I feel like now we can't get anything done. You know, people are screaming over here, ‘I'm on the left’, ‘I'm on the right’. ‘I'm for the vaccine’, ‘no vaccine’. We live in this world of people that have contrasting philosophies, but get nothing done.

So I love their story. I thought, hey, let me just stay out of the way and let this story be told. Let me get on this train that's going 100 miles an hour. And it just took me to places I didn't know existed in my brain sonically.”

It's a really romantic story.

“It's Romeo and Juliet, basically. Imagine sneaking around like that. You know? That’s hot! Like, you go grandma and grandpa, it took a lot of imagination. I imagine everybody goes to sleep on the plantation and grandpa’s sneaking out. He's as black as the night and she's as white as a sheet. I mean, just that first touch, what was that curiosity? Wow!”

How do you feel now that you've honoured them by telling their story?

“It's emotional. But I feel hopeful. I look at all the bad things going on in the world, I think I changed my view on how I see black and white and all this, I feel a little bit different. My seventh generation grandmother's Scottish, my seventh generation grandfather's African, and I'm here.

And for that to happen in the 1700s, they should have been killed, if we believe the conventional wisdom, but they weren't. They made it, and it makes me feel very positive, very upbeat. I really want to tell their story, and I will.”

White Jesus Black Problems is out now.