To celebrate the 30th anniversary of Let Love Rule, Lenny Kravitz has announced an exclusive UK date at The O2, London on Tuesday 11 June 2019. Support comes from Corinne Bailey Rae and protest rock collective Brass Against. Tickets are available from AEG.

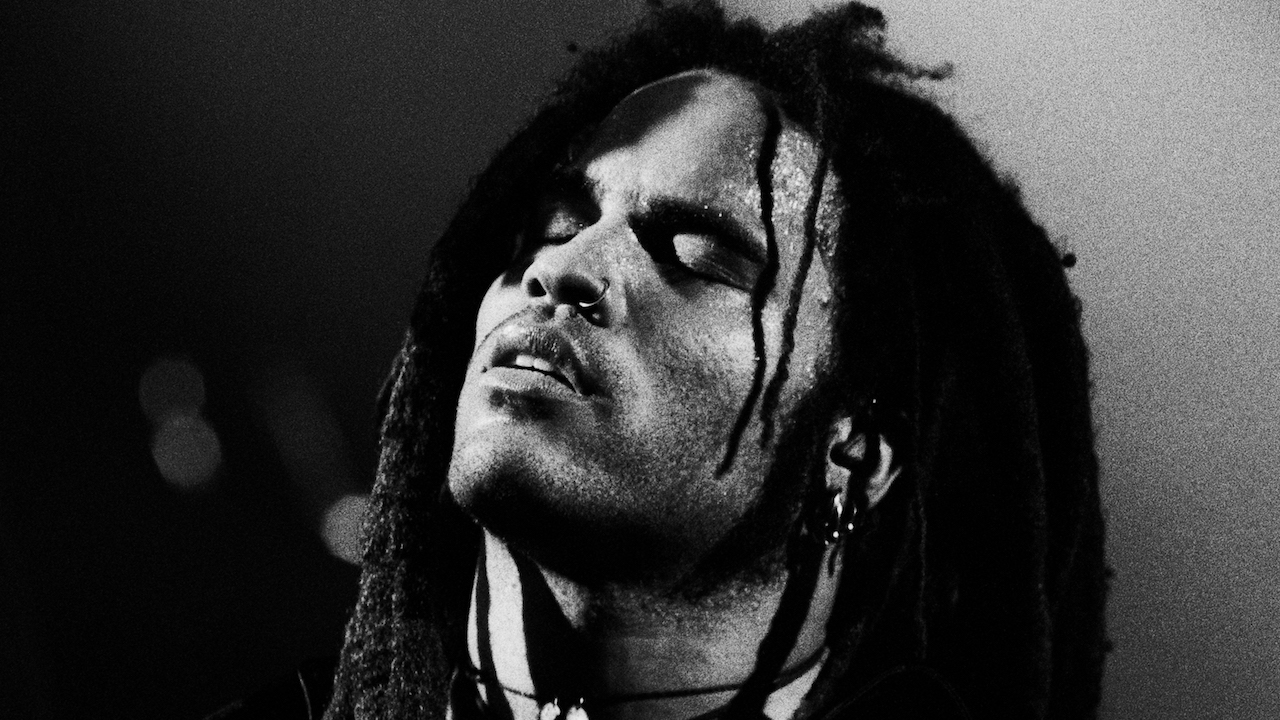

A stone’s throw from the traffic thundering noisily past the iconic Arc de Triomphe lies an oasis of opulent calm. The Hotel Saint James Paris resembles a minor 19th-century palace, with a gated drive away from the bustle of the street. It’s just past noon on a hot day and Lenny Kravitz, wearing a black shirt and jeans with snakeskin shoes, is holding court. He’ll slip away for lunch at his nearby home – one of several scattered around the globe, including the private Bahamas beach where he keeps a caravan and a recording studio.

Since 1993’s Are You Gonna Go My Way album turned him into an MTV staple, Kravitz’s music has often had a slick style suited to plush environments. But between takes on The Hunger Games: Catching Fire set (in which Kravitz plays Jennifer Lawrence’s stylist), the singer/multi-instrumentalist found himself writing gutsier music.

“It brought me back to being a guy with a guitar, making raw music without much thought,” Kravitz says of his latest album, Strut, his tenth. His voice has the grit which made his early singing recall Al Green, but his words come out even and easy.

Recorded in his Bahamas hideaway, with Kravitz producing and playing everything, Strut has a polish by legendary mixer Bob Clearmountain but the most focused rock energy in years. Recording it reminded Kravitz of his feelings as he first started making music. So he’s ready to look back to the eclectic albums with which he began. 1989’s Let Love Rule and 1991’s Mama Said, recorded on vintage equipment and influenced by classic rock and soul from the late 60s and early 70s, influenced the Black Crowes and Guns N’ Roses; they also led to Kravitz’s befriending by older rockers from Bowie and Jagger to Kiss and Aerosmith.

“I was actually in New York two days ago,” he muses, “and I was driving past the place where I used to live at 450 Bloom Street where I made those first records, which now is all very nice. Soho then, especially on Bloom Street, was quite… gritty. And I saw my upstairs neighbour, this lady I hadn’t seen in years, and I recognised her – from the back! Our families grew up together. I used to have Thanksgiving and Easter with them, they’d invite me up. And so I was just there at that place where Let Love Rule was conceived and made.”

Almost since his birth in 1964 there was something of the golden boy about Kravitz. His Bahamian-American actress mother, Roxie Roker, a star in 70s sitcom The Jeffersons, took her son to shows and gigs. Father Sy Kravitz was a Jewish-American TV producer and part-time jazz promoter. Giants of the black artistic world were house guests as Kravitz grew up in New York; jazz great Duke Ellington played Happy Birthday to five-year-old Lenny.

Kravitz agrees it’s significant that such stellar musical figures were around him from the start. “Absolutely. It was all part of the road map. I got to watch these people, be around them, see them performing and personally hanging out with us. Duke and Miles Davis, and great writers, like Maya Angelou, and Nina Simone were around our crew. And you’re watching your mother act in plays, and you see people around and they’re doing poetry readings, and there’s Lorainne Hansberry – she inspired Young, Gifted And Black. I mean, wow!”

When his family moved to LA in 1975, Kravitz found the rest of his musical soul. “I’d left New York City,” he explains, “where it was all about R&B and soul, gospel and jazz. And then I went to LA, and at that time the whole Dogtown skateboarding scene which I became part of were listening to English rock, and Hendrix and American rock’n’roll as well. That’s where I learnt about Led Zeppelin and The Who and Queen and Jimi. That electric guitar side of it – that heavy, distorted, powerful feeling.”

The West Coast in the 70s was perfect for Kravitz. He built his own world in his bedroom, where he set up a drum kit, guitar, bass and amps. “After Let Love Rule my mom was like: ‘Oh, that’s what you’ve been doing,’” he says. “I never shared it.” When he wasn’t honing his talent, the skateboard scene filled his time. “I remember one of the first skateboards, before it even had wheels on it, with the hand-drawn Dogtown sign. I spent a lot of time on the beach, and riding my skateboard up and down the streets, and hanging out at kids’ houses, and jamming. Smoking great weed. Because the parents were all hippies, and it was just a very loose, chilled atmosphere.”

But his relationship with his ex-US Marine dad was less than chilled. In 1979, aged 15, Lenny left home. He had already made his gig debut, singing Mahler with a choir at the Hollywood Bowl. “I had to get on my path,” he remembers. “I knew what I wanted to do when I was five. So by the time you’re fifteen, you’re: ‘Well, I’ve been knowing this for ten years now – let’s go!’ The streets of LA and the streets of New York are what taught me.” His privileged life was largely left behind. “I worked in a fish market, cutting and gutting and frying fish. I worked in a clothing store, I worked in a shoe store, I was a dishwasher in a macrobiotic restaurant.”

By 1987 he was back in NY with girlfriend Lisa Bonet (above, with Kravitz), who starred in The Cosby Show. The globally famous Bonet and her unknown boyfriend married that year. After eight years of struggle he ceased to be Lenny Kravitz, answering to ‘Romeo Blue’.

“I wasn’t comfortable being myself yet,” Kravitz explains of his 80s alter ego, “and I thought Lenny Kravitz was the most ridiculous name for anybody trying to make music. It was that time when people were having these very theatrical names. Someone called me Romeo, because they thought that I was very much a ladies’ man: ‘Oh, check out Romeo!’ And I added the Blue part. I was thinking about a mesh of Ziggy Stardust and Prince.”

It was Romeo Blue who unsuccessfully knocked on every major label’s door. “Depending on who was listening, I either wasn’t black enough or wasn’t white enough. It was rock but it was funky, it was R&B but it was too rock. It was usually this thing of being caught in between. Because at the record companies you had your black music division, and your other music division.”

Does it bug Kravitz that, as it has been since his debut, black radio in the US still won’t touch him?

“It’s just the way it is,” he says equitably. “They played It Ain’t Over Till It’s Over. They played certain ones. I don’t agree with it, but I understand that people have their formats and their advertisers. It’s too bad that things are so segregated.”

Is it disappointing that he’s still seen as unusual in playing rock; as if it’s assumed to be white music?

“That’s always weird. I mean, it belongs to everybody, but we know who invented it, who it came from,” he says, his placidity ruffling just a little. “My music is very mixed, but it has a lot of rock’n’roll in it – and I’ve even had black kids say: ‘How can you play that white music?’ Know your history.”

It was at a studio in a disused factory in Hoboken, NJ that Kravitz found a kindred spirit.

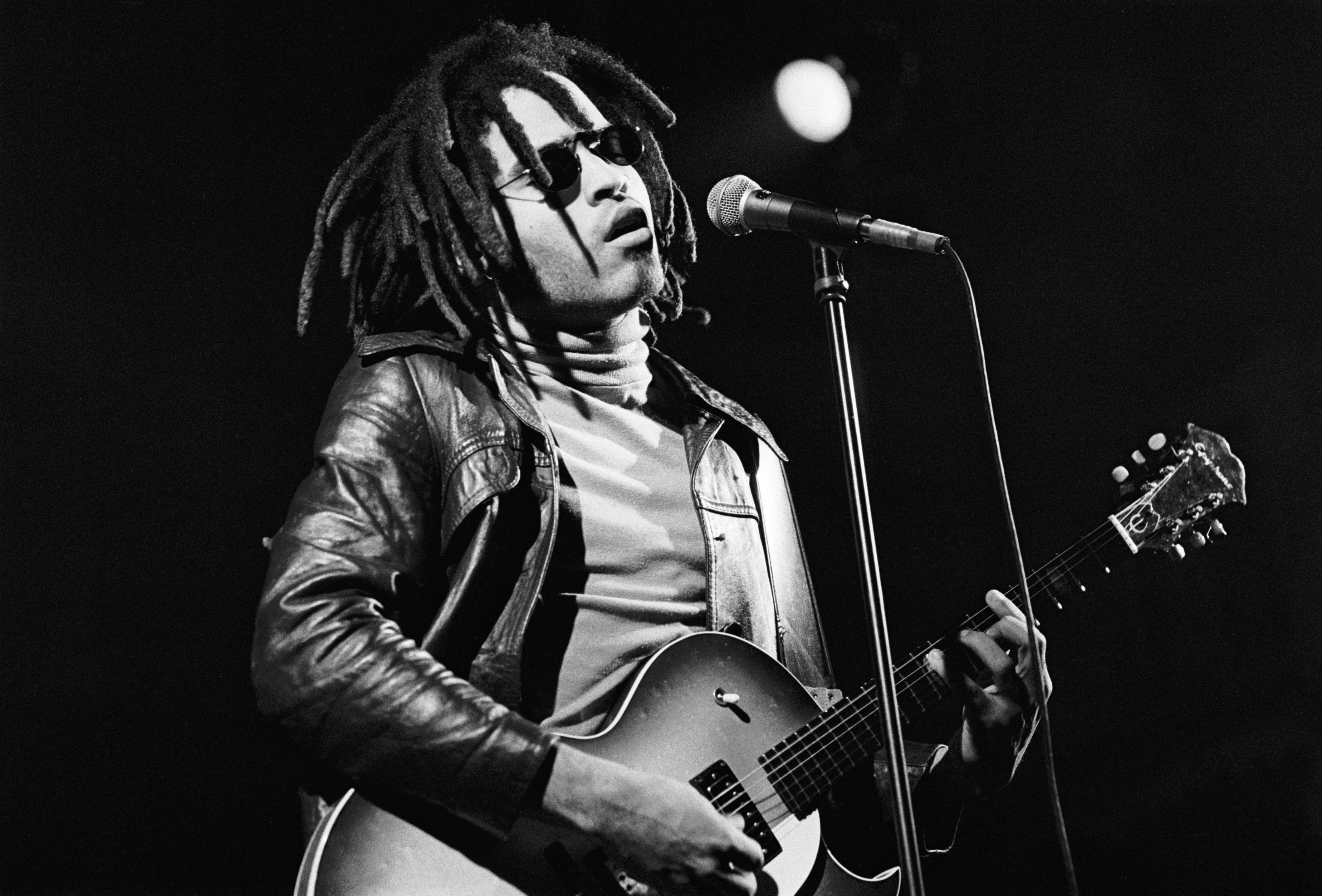

“Henry Hirsch came from New York City,” he explains. “He was a keyboard player who’d gone to Germany and had a couple of hits, and he then learned how to engineer, and had a very unorthodox technique, really raw. I came to his studio on the waterfront with another band I was playing with, and he and I saw things eye to eye. I ended up leaving that band to do my own thing. That was Let Love Rule.

“I was in LA, and my wife at the time was pregnant. At that time there weren’t many people around who were into the vintage thing – it was 1987 and ’88. We were into the old equipment, with the older sound. Not because it was romantic, but because it sounded so damn good. He had very basic equipment, like an old Trident console. I called him, and I remember saying: ‘I wanna make this real intimate, personal record that sounds carpety – very plush and warm.’ And he got it. He’s a big reason why I ended up playing all the instruments on the record. He said: ‘It has more character when you play it.’”

The major labels were still unimpressed. Until Kravitz talked his way into Virgin Records in LA to meet A&R person Nancy Jeffries, as she was about to leave on a Friday afternoon. “She said: ‘I’ve got fifteen minutes.’ I had a cassette, and popped in the song Let Love Rule. And she said: ‘Wait here a minute.’” One by one, more execs were brought to listen to Kravitz’s tape. “They kept writing on papers, and passing them back and forth. And at the last song, they looked at me and said: ‘Do you want a record deal?’ I was in shock. When I looked at the papers they’d passed, they said things like: ‘John Lennon Meets Prince’. And they told me straight up: ‘We can’t say this is gonna sell, because it doesn’t sound like what’s on the radio. But we really dig it.’”

Romeo Blue was killed off before anyone knew he’d lived. “I realised I was Lenny Kravitz, and I should deal with it.”

As Virgin had feared, the Let Love Rule album made little impact in the US. With vocals veering from Al Green screams to the Lennonesque Be, the dirty guitar of Blues For Sister Someone, and Flower Child’s beatific hippie flashback, critics sneered at its retro stance. “The influences are there, like you can hear in anybody,” he says of the charge. “But I always made my own music.”

Kravitz wasn’t as alone as his label supposed. Guns N’ Roses had recently relaunched Zep-style guitar aggro and sent it to the top of the charts. The Stone Roses mixed acid house with The Beatles. Dylan, Lou Reed and Neil Young returned from the wilderness with great new albums, and ‘retro’ ruled.

“The Black Crowes had Let Love Rule in the studio the whole time they were making Shake Your Money Maker,” Kravitz says. “The CD was right up there on the console, and they’d be referencing it.”

Kravitz was by now signed to the powerful agents CAA. He’d never played a rock gig. But after a brief warm-up in the clubs he supported Tom Petty, Bowie, Dylan and The Cult. He’d found his golden touch.

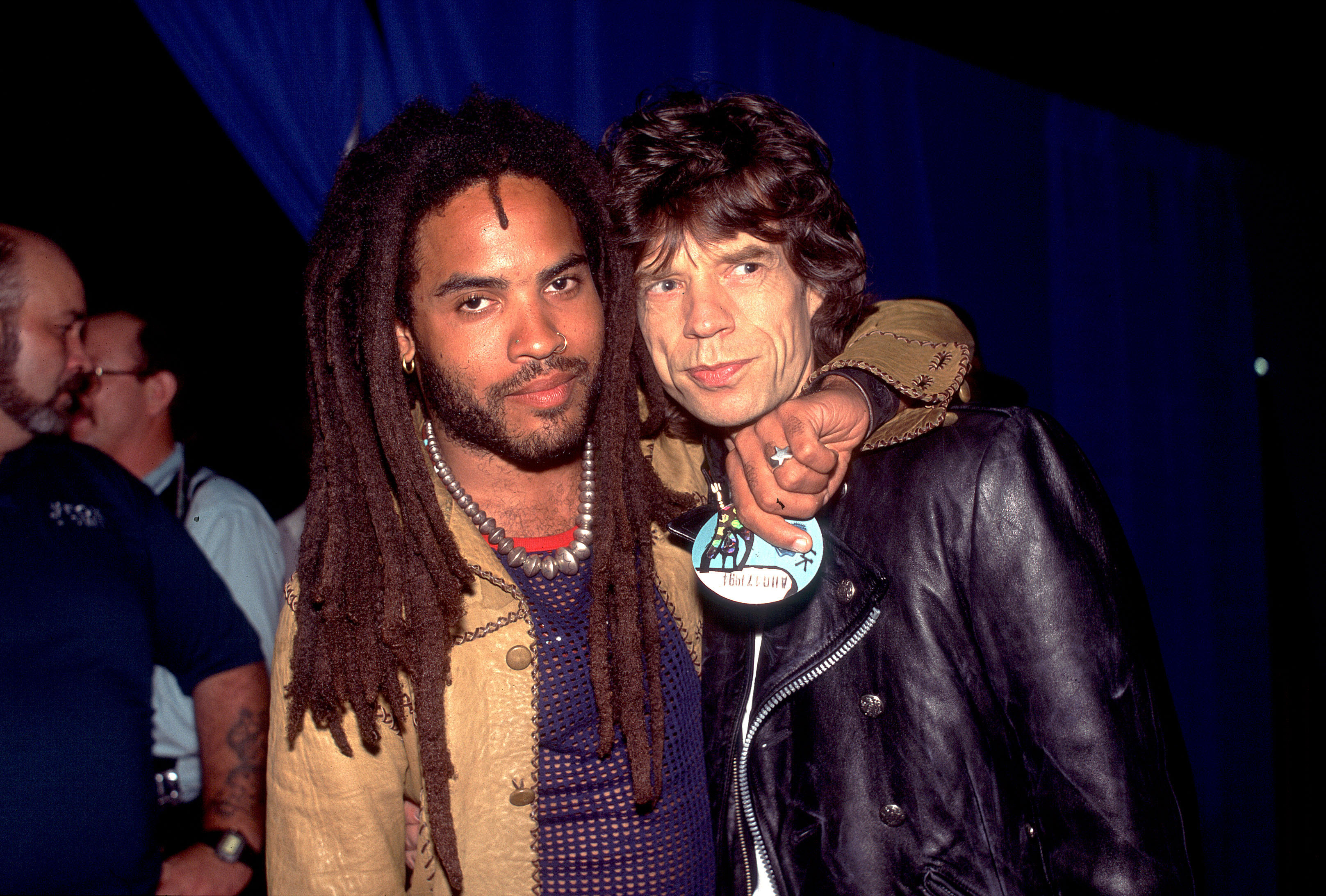

“Tom Petty was the first to take me out,” Kravitz confirms. “Thank you, Tom. And I got to open for Bowie at Dodgers Stadium. It was freaky. But once I got up there it felt really great. We had to work, because they were not there to see us. But even opening for the Stones later, and their audiences don’t fuck around, we got them.”

Veteran rockers were delighted to hook up with a young star indebted to their music, even if some of the meetings were odd. “Dylan was in his underwear,” says Kravitz. “His wardrobe person was ironing his pants.” He became a friend though, along with Bowie and Jagger. “Mick came backstage on my Mama Said tour, here in Paris. I said: ‘Mick, man, since you’re here, why don’t we do No Expectations from Beggars Banquet tonight?’ We started working it out on guitars in the dressing room, and here I am, at my show, doing Stones tunes with Mick Jagger. You meet people that taught you, and now you’re playing with them.

“But my heroes got it: Curtis Mayfield, Al Green, Robert Plant and Mick Jagger, digging me and hanging out and coming to see me. Joan Baez used to come over to my place. I’d be this kid in my loft in New York, and Anita Pallenberg and Yoko would be coming to hang.”

Kravitz returned to Hoboken to follow up Let Love Rule. But his life had taken a disastrous turn. Amid denied rumours of an affair with Madonna (for whom he co-wrote UK No.1 Justify My Love), he and Bonet separated. Kravitz responded with a break-up album.

Slash’s solo on opener Fields Of Joy came after Kravitz met him at the American Music Awards. “Axl was wearing a ‘Let Love Rule’ button on his leather jacket,” he remembers. “Slash came up to me and said: [drawls] ‘Man, I got laid to your records so much, man.’ Then as we were talking, I said: ‘Dude, didn’t we go to high school together?’ It wasn’t that many years before, but we looked different. We said: ‘Man, we should do something together.’”

After a Guns N’ Roses European tour, Slash “arrived at eight in the morning, and went right to my loft,” Kravitz remembers. “I had to go to that same upstairs neighbour that I bumped into this week, and wake them up to borrow a bottle of vodka. And then we went straight to the recording studio – at nine in the morning. He thought I was out of my fucking mind. And we did Always On The Run right there.”

It Ain’t Over Till It’s Over didn’t have its intended effect – separation turned to divorce in 1993. But it lifted Mama Said into the US Top 40 and UK Top 10. It laid the foundation for Are You Gonna Go My Way, and the rest of Kravitz’s career. Now, the man serenaded as a child by Duke Ellington records in his own studio, on his own beach. Does that make any difference?

“I’m not on the subway or getting in my van and driving through the Holland Tunnel,” he considers. “But once I’m working in the studio, whether I’m in the Bahamas or in some shit-hole in Hoboken, the work ethic and the feeling is still the same. Because the expectation is something’s gonna happen. And when that thing starts to happen, it’s the rush that it was in high school.”