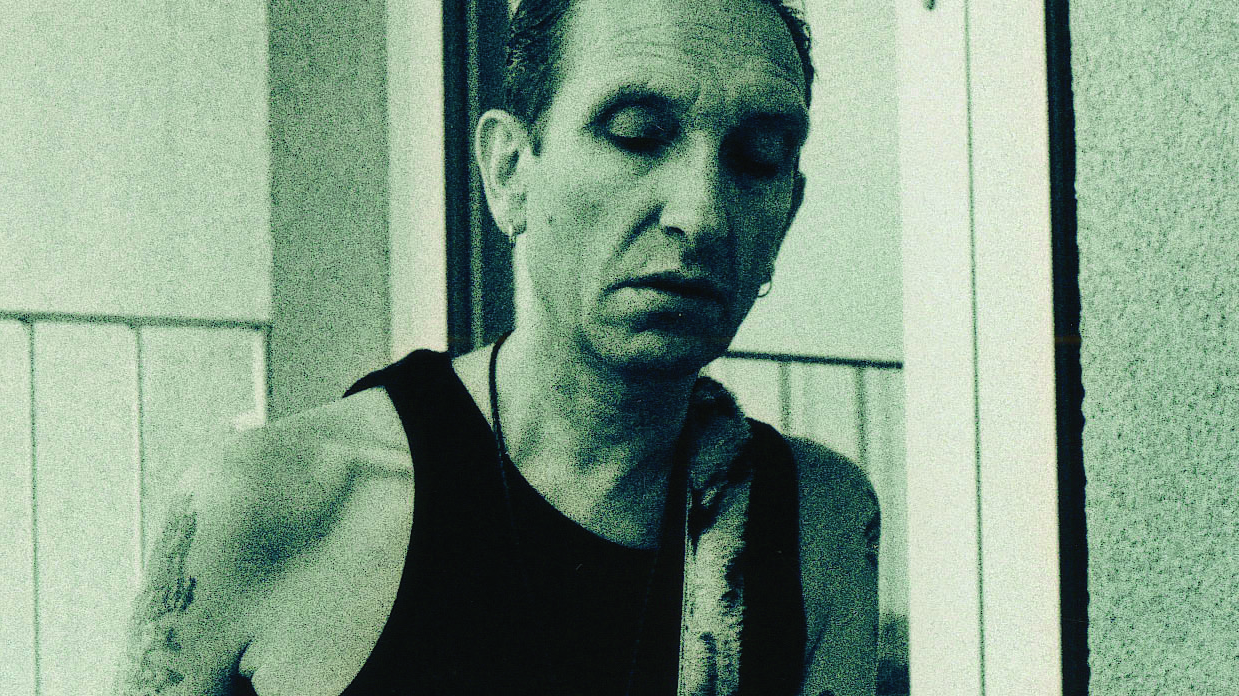

Southend’s Steve Hooker has been making music since the late 70s, first with The Heat, then with The Shakers, Boz And The Bozmen, Rumble and, since 2004, Stripped Down Stompin’ Band. He’s also collaborated with a wealth of musicians from Wilko Johnson and Steve Marriott to the Pretty Things’ Dick Taylor.

What’s the story behind your new album, Duende Blues?

‘Duende’ means ‘soul’ – it’s a term often used in flamenco and what you have on the album is bar-room rockabilly, bottleneck blues and country soul, Stripped Down Stompin’ Band, harmonica sweetener and a naked icon wrapped up in river pirates parchment. One long soul ballad has been left off the final running order due to the personal lyric – it’s a bit close to the bone. This is the second time we’ve self-censored – there’s a missing track from the last album, Smokin’ Guitar, in the vaults, too.

You once said, “I’m fussy about mastering and the gaps between tracks – I’m as much of a Motown guy as a rough-and-ready bluesman.” Discuss.

I prefer the production on Motown or Hi Records to the more earthy sounds like Sun. I think the Chess brothers had a far better ear for the bluesmen than Sam Phillips. I used to think of vinyl albums as two performances, like a club gig. I want a record to flow like a film or a story. Once we have a few tracks down, I put the rest together around them, start to finish, with that in mind.

What are your memories of being in your first band The Heat in 1977 and touring with Wilko Johnson?

From Uxbridge University to Liverpool’s Eric’s, through Leeds’ F Club, Dingwalls, Birmingham’s Barbarella’s, the Hope & Anchor and the Nashville to Aylesbury Friars, it wasn’t Highway 61 or Route 66, but we lived out most of the rock’n’roll fantasies of violence, sleaze, dope and musical mayhem. We played mostly original songs and covers we liked: Knock On Wood, Little Queenie, 96 Tears. I remember The Slits turned up at Dingwalls. Viv Albertine hung around to talk through most of Wilko’s set after we played. Things were slow after that tour though. I had no home phone, no manager and no offers from major labels. We had to start knocking on doors and the best thing we came up with was a gig at the – by then – rundown Roxy club. Everything went well until the hissing manager ran on stage and ejected us for playing rock’n’roll behind the hallowed doors of punk rock.

How did your relationship with the blues begin?

My parents were big jazz fans, they had a few records by Big Bill Broonzy and Lead Belly, and after making the connection between them and The Beatles and the Stones I wanted to dig deeper, and of course I found the devil waiting down there and he was Sonny Boy Williamson. That album, Down And Out Blues, influenced me as much as Robert Johnson’s King Of The Delta Blues Singers. I was lucky to have heard Sonny Boy and [Howlin’] Wolf around the same time as The Animals, the Stones and Them, because then I understood where they were coming from and that they didn’t just want to hold somebody’s hand.

Was there a musical epiphany?

In 1964, I saw the Stones play Around And Around on TV. ‘When the po’lice knocked/Them doors flew back’ – that blew my mind, the idea that they or Chuck Berry played so loud they couldn’t hear the Old Bill knocking. I was like, “fuck school and everything else” from then on.

You shared a stage with Steve Marriott in the 80s.

The Shakers were booked as support for one of his comeback shows at Dingwalls. As we were soundchecking I noticed a peculiar echo effect on the guitar but I just played on, assuming the soundman was messing around with the FX. Then I looked across the stage and saw Steve had got up and plugged his Telecaster in and started jamming along, because he dug it.

You also worked with Dick Taylor.

I did troubleshooting work for small record companies, booking sessions, finding musicians and, in the case of Dick Taylor, Pretty Things N’Mates, working out some of the tunes and playing guide guitar or singing guide vocals. I was lucky enough to walk away with a mix of me playing and singing Pushing Too Hard with those guys when Phil [May] was at his club.

You cameo in the Danny Garcia-directed Looking For Johnny film about Johnny Thunders.

I was real fond of Johnny. I learned the best way to get on with people is to give them space and not ask a lot of questions. NYC people are similar to us in Essex: sharp and sarcastic.

What do you listen to when you’re on the road?

Taj Mahal’s self-titled first album is never far from the CD player in the car. I wish he’d stuck with that Otis thing

a little longer though.

Duende Blues is out now on Raucous.