If you’re of the opinion that an artist needs to be put through life’s wringer in order to be sufficiently inspired, well, Fish could write a book about it. In fact, that’s what he’s already doing, aiming to publish his memoirs once he’s finally put this pesky music career behind him.

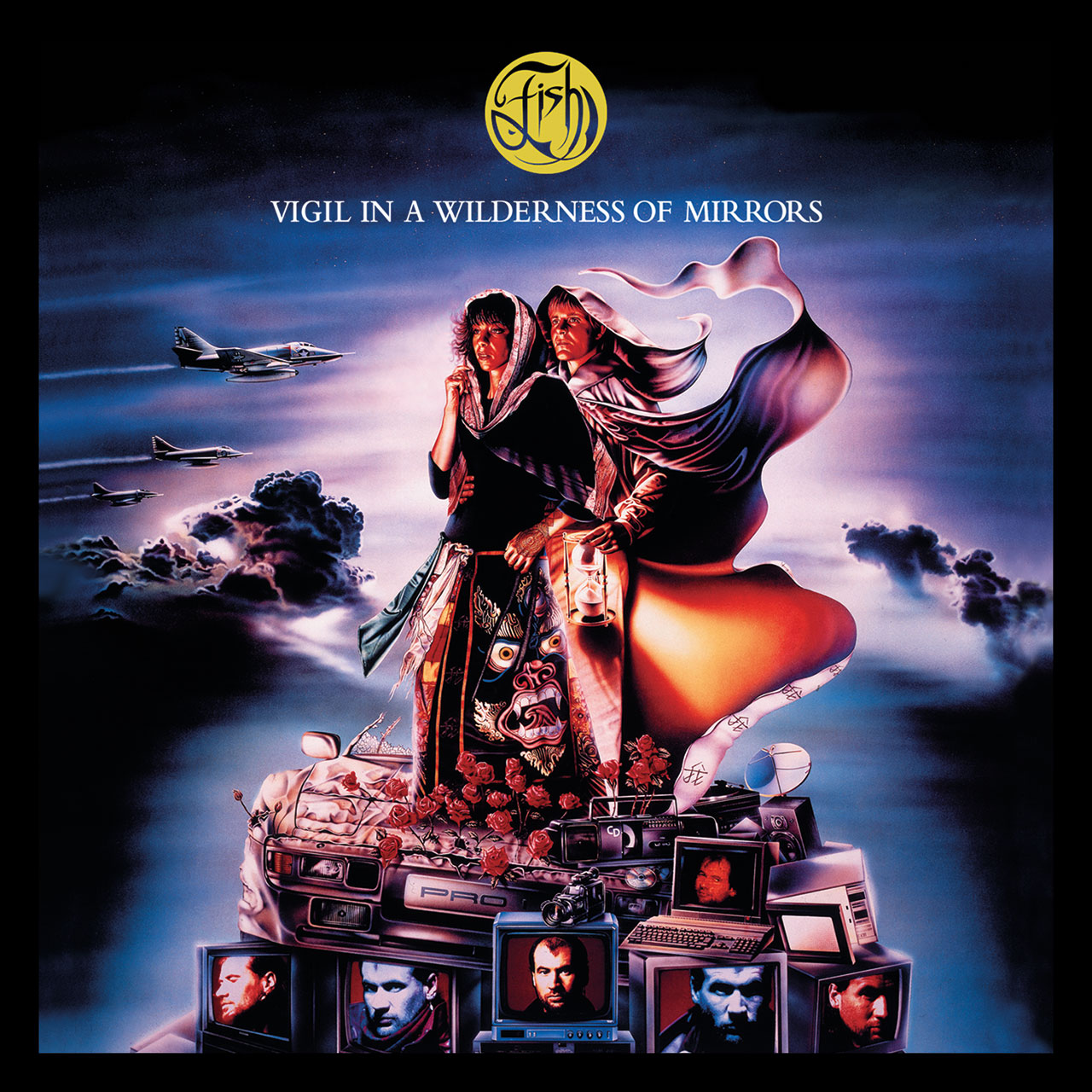

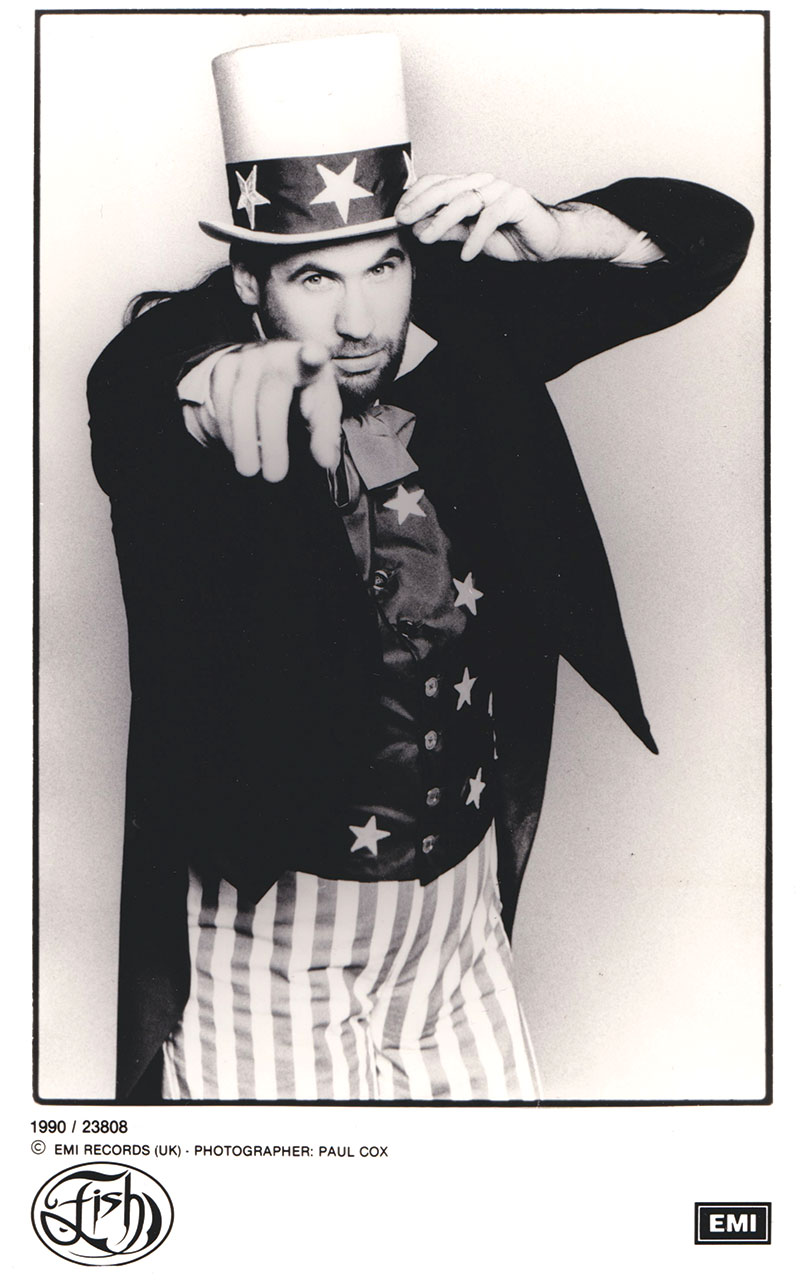

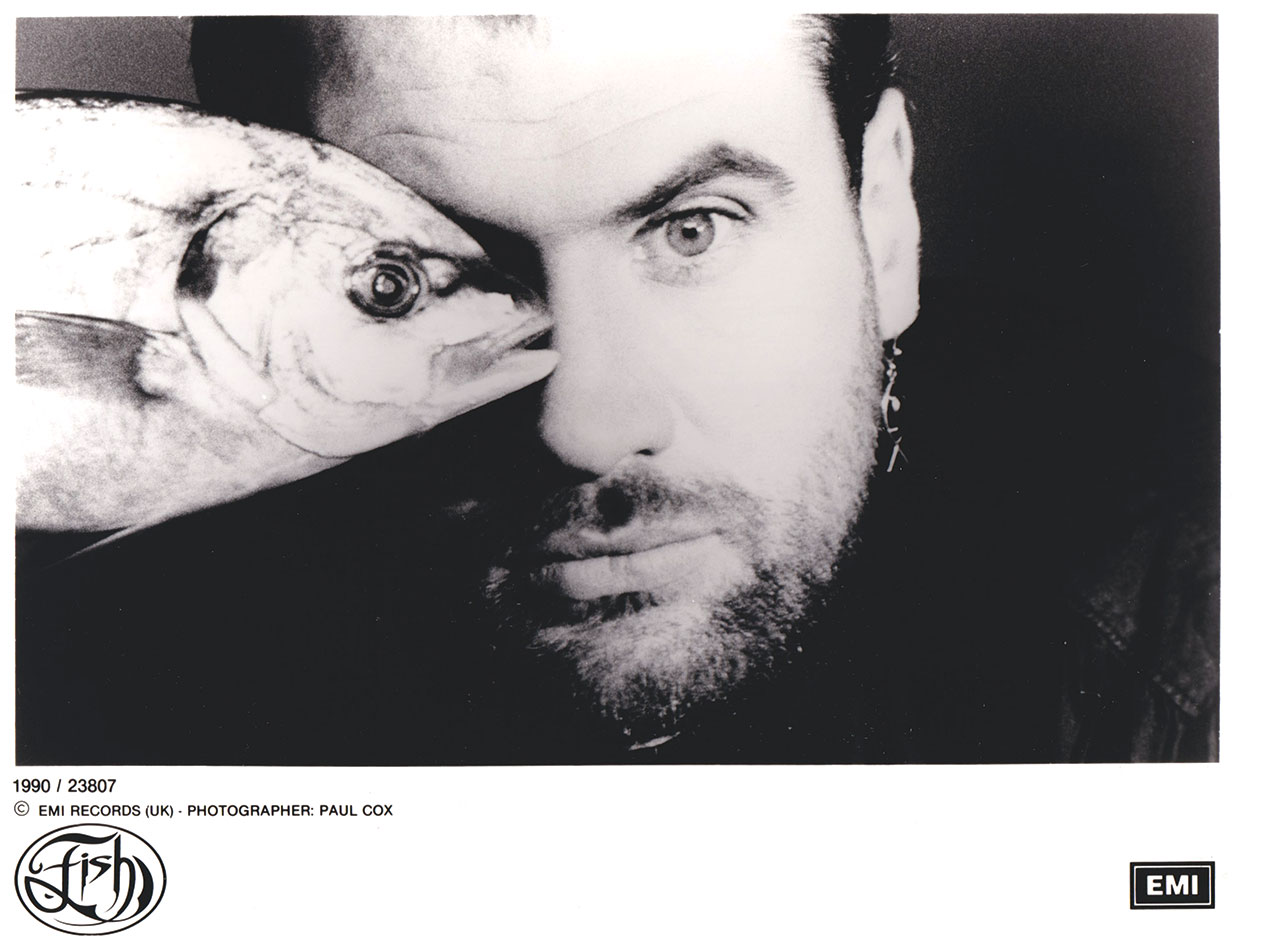

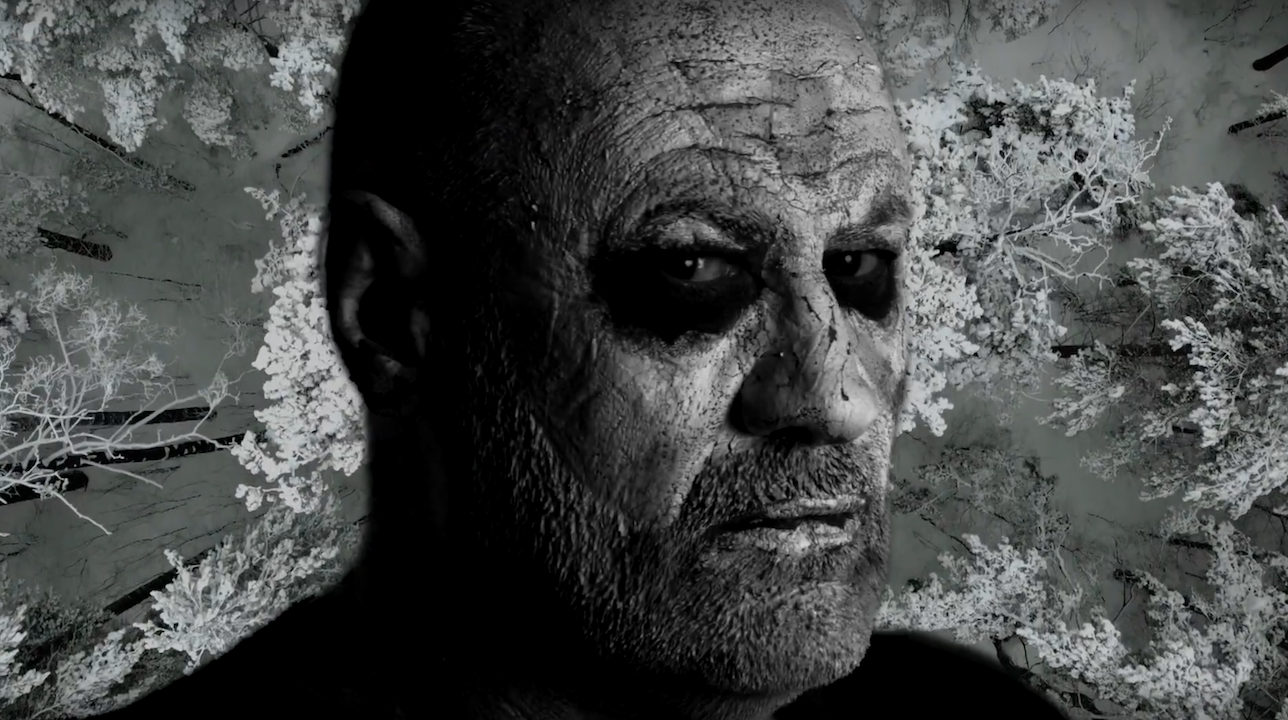

Seasoned Marillion fans will surely have read chapter and verse on that band’s story over the years, much of it in these very pages. But as for what happened next for their original frontman – it’s a less well-documented tale. With next year’s tour (pandemics permitting) celebrating the two bookends of Fish’s solo career, focusing on new album Weltschmerz and his 1990 debut Vigil In A Wilderness Of Mirrors, and his imminent retirement from music still on the horizon, we got this giant of modern prog to take us through that 30-year solo journey, and the turbulent tales that provided its backdrop.

New Beginnings, Old Problems

Within days of Fish’s exit from Marillion during rehearsals for the follow-up to 1988’s Clutching At Straws, a very public row was ignited. Fish still winces at some memories of it: “I’ve looked back at some of the press at that time and gone, ‘Oof! I wish I’d never said that.’ But it was an emotional time.”

Just a bit. But for Fish, there were still positives. Despite reluctantly agreeing to EMI’s request to delay Vigil In A Wilderness Of Mirrors so as not to clash with Marillion’s first post-Fish outing Seasons End, the album still performed respectably – imagine notching up a No.5 album on the back of three Top 40 singles now. And the new dawn felt good.

“I’d just walked through a hugely successful band for reasons that most fans found inexplicable. So the pressure was on. But when I found Mickey [Simmonds, new co-writer and keyboard player], I was dealing one on one with someone, and I could do what the fuck I wanted without having to come through a committee. That freed me up, and made Vigil… a great album.

“If you look at The Company, you look at Family Business, you look at Big Wedge: they were fully realised songs. You still had the Marillion elements like Vigil, which is a longer song. You had View From The Hill, which was a nod to my Who-ey, rockier side. And then you get A Gentleman’s Excuse Me – a beautiful song.”

Yet at the same time, he and EMI were clearly on a collision course.

“Every time I wanted to make an album, I had to go to them and get an advance with the studio, they had complete control of the material. And promoters wouldn’t book gigs unless they knew EMI was providing tour support. I wanted my independence.”

Which is roughly when, after deciding to move out of London with his then-wife, German model Tamara Nowy, and their newborn daughter, he had an idea.

“It was just a farmhouse with rundown outbuildings, but I fell in love with it. I had the vision,” he remembers.

“One of the reasons I – and Marillion – ended up owing so much to EMI, was every rehearsal, every residential writing session came off our royalties. Here I could be in control of the situation and bring people up when I wanted to have them stay. And it worked for me. It was a lang sair fecht [long sore fight], as they say up here… for a number of years this studio was like a fucking concrete albatross around my neck financially, but if I hadn’t gone through that, I wouldn’t be here.”

This return to his East Lothian roots also reflected a reconnection with his own Scottishness, which would become evident on his second solo set, Internal Exile (A Collection Of A Boy’s Own Stories).

Even if his dispute with his old band had yet to be resolved, and he also had to fight EMI to let him leave and sign to Polydor (“I was writing the album with a head full of legalese”), Internal Exile wasn’t short on spirit.

While the tin whistle-laden folk of the title track, and its video featuring traditional dancers, reflected an upbeat, unironic celtic pride, there was righteous anger crackling within Credo, reflecting a newly politicised Fish who saw how his homeland was suffering.

“I was up here and the poll tax was going on [the hated ‘community charge’ was tried out in Scotland a year before the rest of the UK], and I found myself in the company of some very politically oriented people. They opened my eyes up,” he says.

Meanwhile, though, Just Good Friends and Shadowplay suggested all was not well on the romantic front and more pressingly, the album, released on Polydor after a suitably acrimonious parting of the ways with EMI, didn’t sell in the numbers Fish and the label had hoped.

He partly blames himself (“We wrote great songs on the album but as an album, it wasn’t cohesive”) but the only way to rectify the situation, in Polydor’s eyes, was for Fish to come up with something else. Now.

“They wanted another album, I was paying off all this interest on the studio… so the only option was to put an album together quickly.”

Songs From The Mirror, an album of covers, revisiting some favourite songs from his youth, was the result.

“I needed to rediscover the magic of the music that had brought me to the point,” he says. On the other hand, he also compares it to “a coyote caught in a trap where you bite your fucking leg off to go,” because Polydor wouldn’t commit to putting out another album of originals after this one. It has some standout moments, though, not least his brave attempt to offer a male- voiced version of Sandy Denny’s Solo. “I related so much to that lyric,” he says, “and it’s one of my favourite songs on that record, next to Five Years, the Bowie one.”

State Of Independence

In 1993, Fish began to manage himself, and go it alone label-wise, with the launch of the Dick Bros Record Company, on which he released 1994’s Suits. By this time, the songwriting set-up had evolved, with chief musical contributions coming from producer James Cassidy and Foster Paterson on keyboards. Although the album made No.18 in the UK charts, Fish was still getting to grips with doing things himself, and he didn’t have the resources required.

“I spent the money on the album and then you got the promotion, I was having to learn all this stuff… but there were some beautiful songs on Suits, which I still play now. When I played Emperor’s Song a couple years ago, it sounded so fresh. It was lovely.”

The lead single, meanwhile, Lady Let It Lie, seemed to betray some bleak feelings in its writer, admitting: ‘I don’t want to be me no more.’

He pauses.

“Well, I’ve got to put that in perspective. During the recording of Vigil I came up to the house and I discovered my wife was having an affair. And I had to go back during the recording of Vigil and sing Cliché after I discovered that.

“My marriage was just fuckin’ disintegrating, and I would go on the road to escape. But my daughter was born in January ’91, and my DNA is like, you’ve got to be a family guy, so I didn’t want to give up.”

However, a more fruitful relationship would soon emerge on the professional front with a new collaborator. “Steven Wilson was an absolute breath of fresh air. He had new ideas, a different approach, and he started just sending stuff up to me. And then it was like, ‘Well, yeah, that works.’ So I decided to really invest in that album.”

History backs up that decision in the sense that the resulting 1997 LP, Sunsets On Empire remains among Fish’s best-loved solo sets, although Prog can’t imagine all of it being as well-received in 2020’s cultural climate.

Touring further afield after Suits (including an eye-opening visit to war-torn Bosnia in 1996) inspired pointedly polemical lyrics such as lead single Brother 52 and the opening track The Perception Of Johnny Punter, which opens with a string of racial epithets that evoke the hatred and intolerance still being stirred up across the globe, but which would surely trigger an almighty Twitterstorm if it was written now and, inevitably, taken out of context.

“I’m a fan of Lenny Bruce,” he explains, “and it was inspired by one of his stage performances [where he racially insults everyone in his audience], and he’s trying to say, ‘They’re words, and the more you use them the more you disempower them.’”

Whether or not readers agree with that, Fish’s “investment” in Sunsets… ensured a rich production with mastering in the US by Bob Ludwig. “It was a brilliant sounding album and I’d got a chance for a release in the America. The world was my oyster again, for a moment… until I opened it up and found out there was a turd inside it. We ran out of money, basically.”

Death, Debt And Divorce

By the time the next Fish album of original songs, 1999’s Raingods With Zippos, came to be made, budgetary restrictions were making their presence felt in more than just promotion. Many fans still complain of a flat sound to this album and its successor, and while Fish is loath to criticise producer Elliot Ness, he does still wonder about what might have been, particularly when it comes to the 25-minute centrepiece of the record.

“If Plague Of Ghosts had been recorded by [current Fish producer] Calum Malcolm it would have been a fucking epic,” he says. “If we’d had Calum’s knowledge and experience of arrangements and how to decorate songs…”

Meanwhile, Steven Wilson was contributing guitar but didn’t co-write any tracks, and the song credits are many and varied, reflecting a period of rebuilding on several fronts.

By the time Fellini Days followed in 2001, thanks to overspending on recording and tours and crippling bank interest, he admits, “I was nearly 900 grand in debt.”

The Dick Bros label had gone under, meaning Raingods had been put out by Roadrunner, and Fellini Days came out on a new self-launched indie label, Chocolate Frog. Meanwhile, his marriage finally bit the dust.

“If you want a song to illustrate how I felt, listen to Long Cold Day on that album,” he says. “Our Smile is on that album too – that was about an affair that I was having in 2000 before my wife left. I met somebody and I went, ‘Wait a minute, I’m actually I’m happy and I’m smiling.’ Then my wife left me for good in 2001. She’d been having another affair.

“When we had the meeting in 2001, it was like, ‘I want half of everything.’ I’m like, ‘Cool. Write me a cheque for 450 grand, you can have half that debt!’”

The finances were eventually sorted (“it took an awful lot of manoeuvring”) chiefly through the sale of most of Fish’s house. “All I kept was the studio, but thank God I did,” he concludes. “It’s the best place I’ve ever lived and it’s still my home.”

Two Weddings, A Court Case, And A Creative Rebirth

The next major songwriting collaborator for Fish turned out to be his chart contemporary from Marillion’s prime, Big Country’s Bruce Watson. The album they co-wrote most of, Field Of Crows, is another with bittersweet associations for the gentle giant, since that was when he discovered the office manager he’d hired in the early 2000s to deal with mail order, merchandise and the like, had been up to no good.

“I reckon she took us for round about 100-150 grand,” he says, and although he won a civil case against her, she disappeared and still owes him money.

Things were at least still ticking over creatively. Field Of Crows isn’t a Fish album often mentioned among his solo highlights by fans, but if the blues rock undercurrent beneath tracks such as Innocent Party and The Rookie were an acquired taste for Fish-heads, ballads such as Shot The Craw and Exit Wound were as affecting as anything he’d previously done.

The seeds would also be planted for a new creative partnership that would bear fruit on the next album.

“Steve Vantsis, my bass player, had been on about having a go at writing,” Fish explains, “We started to play about with things and came up with some really interesting ideas.”

The first building blocks of what would become 2007 album 13th Star duly took shape… and then, as ever with Fish, life intervened.

“Around that time,” he says, with a slight weariness in his tone, “I got involved with [former Mostly Autumn singer] Heather Findlay. It was all hunky dory and we were going to get married. I was working on the album, had a bunch of lyrics for it, and then, kaboom! She walked out. I think it was about two months before the wedding, with everything booked.

“It was like someone had put a frag grenade in my head. Steve was working in the control room, and I was going out to the greenhouse and writing all these lyrics about the situation I was in. I went from being completely broken-hearted, completely confused, to being very fucking angry. I still am. I wouldn’t go out of my way to do anything, I just leave it up to karma. And my karma was a fucking brilliant album.”

The qualities of 13th Star lie not just in piercing lyrical dissections of heartbreak such as Circle Line, Dark Star and Manchmal. The multi-instrumental creativity of Vantsis allied to another newcomer’s work – the bold, dramatic production of Calum Malcolm – put the heart back into Fish’s sound again.

Walking Back To Happiness

Were calmer seas on the horizon? No such luck. As he entered his sixth decade on Earth, things would get even worse before they got better. “I’d been having problems with my voice. I was walking onto stages and my voice just wasn’t there. It was awful – people were saying, ‘Fish’s voice is fucked.’”

At the end of 2008 he finally found a specialist who could pinpoint the problem. Literally.

“She said, ‘You’ve got a growth on your vocal cord.’ I said, ‘Is there cancer?’ And she said, ‘We won’t know until we operate.’ I spent three months not knowing if I would have a voice again. It was fucking awful. I went in for that operation, she went in with a scalpel, she touched it, and she said it exploded. She said, ‘You’ve had a cyst on your vocal cords for probably three years.’

“I had that operation, then at the end of 2009 I had another one… in the middle of which I got married again for six months. Tcchhhh!”

He laughs ruefully and lights up another roll-up.

“I thought I was cured,” he says of going travelling to Vietnam after the first throat operation, “And I met Katie. I fell head-over-heels. Got engaged in October and married the following May. And all I can say is I met Felicity Kendal from The Good Life, and then six months later I find I actually married Margo.”

It turned out his intended was not as keen on as she had initially indicated on giving up the bright lights and big city for the rural charms of East Lothian. “I came out from

my second operation on the December 23. My then-wife went down to London on Boxing Day and that was it, she disappeared.”

As the new decade dawned, Fish wasn’t just heartbroken again, but he wasn’t sure if his voice would ever be the same again: “The beginning of 2010 was the lowest I can ever remember being in my life.”

Thankfully, a Fish Heads club tour for fans proved a welcome fillip in the latter part of that year, and he also met his future wife, Simone, a fan since the 1980s.

And nearly a quarter of a century since he clutched his last straw from his disintegrating relationship with Marillion, he’d achieve another creative landmark. His 10th studio album, A Feast Of Consequences, was another adventurous step forward, with the five-part High Wood suite forminga darkly moving, and sometimes se thingly unsettling emotional peak.

The idea formed on a visit to the First World War battlefields of northern France, with the small but strategically crucial area of Bois des Fourcaux (known to the British as High Wood) making a particular impression.

“I’m an ex-forester, I’ve got an affinity with woods, trees. And I saw this wood on this hill, and… it was just pure fuckin’ malevolence.”

He found out his grandfather William Paterson “dug trenches through bodies” on that very ground. “It became personal, and I became completely enveloped,” he says.

That album was signed off with The Great Unravelling, a song Fish admits he “can’t even listen to anymore”, wherein he got to thinking about his own mortality, the lives of his parents and his grandparents.

And it wasn’t long after that when he began to think about a life beyond music. But not before he dealt with a concept that his grandfather would have known plenty about: Weltschmerz.

That brings us just about up to date, and to the question of what’s next for Fish after he finally faces the final curtain as a singer and turns his hand to his other ambitions – screenwriting, a memoir, who knows what else?

“People ask me: ‘What are you gonna write about?’ What don’t I write about? You know, trying to get all the stuff I’ve talked about over in lyrics becomes really claustrophobic. There are so many things I wanna say. I mean, I could write a fucking book about my two days at the Somme, you know. I mean, I ended up sitting… no, no, that’s another story…”

And Prog will surely hear about it in due course. After three and a half hours talking to Fish, we still get the impression that he’s only just getting warmed up. If you think this is the last we’ve heard from Derek William Dick, you’re sorely mistaken. If he has his way, this isn’t the end – just the end of the beginning.

The article originally appeared in issue 112 of Prog Magazine.