"It was if Merlin himself could not have concocted a spell more perfect": how Stevie Nicks turned to mythology to conjure up Fleetwood Mac's Rhiannon

A chance encounter with a fantasy novel inspired Stevie Nicks' witchy hit and helped to resurrect Fleetwood Mac

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

It makes sense that what has become Stevie Nicks’s signature song was inspired by a kind of ancient magic. Bibliomancy, a mystical practice dating back to the 1700s, holds that if a book is picked up and opened to a page at random, the first word or sentence one sees will reveal some kind of epiphany. But the book that Nicks picked up in 1974 – one that would eventually help launch her into superstardom – didn’t exactly seem full of divine promise.

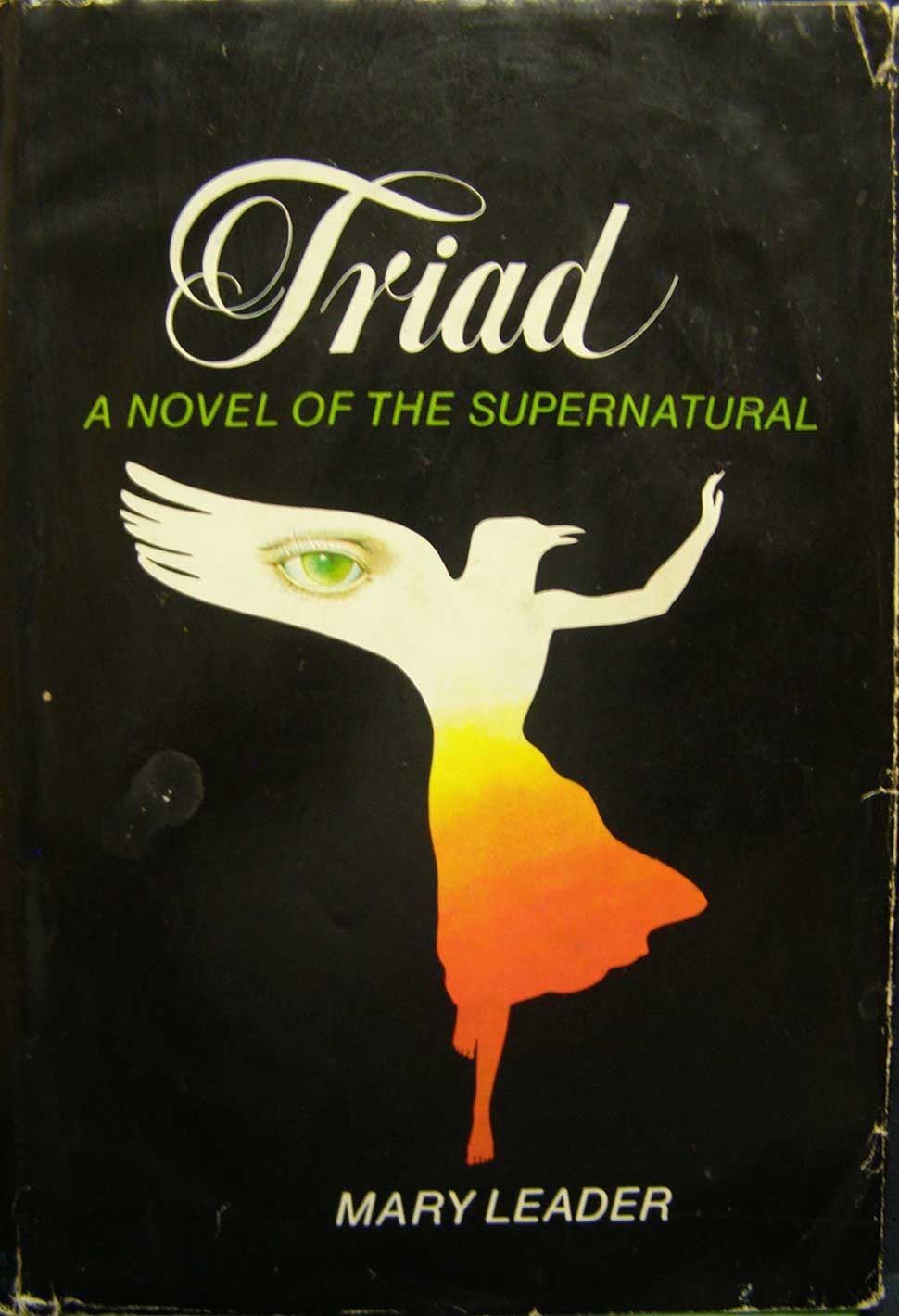

“It was just a stupid little paperback that I found somewhere at somebody’s house, lying on the couch,” Nicks says more than 40 years on. “It was called Triad [written by Mary Leader] and it was all about this girl who becomes possessed by a spirit named Rhiannon. I read the book, but I was so taken with that name that I thought: ‘I’ve got to write something about this.’ So I sat down at the piano and started this song about a woman that was all involved with these birds and magic.

“I still have the cassette tape of when I was first writing it,” she continues. “Lindsey [Buckingham, Nicks’s musical and then romantic partner] came in and I said: ‘We have to go to a park and record the sound of birds rising.’ And he looked at me like I was crazy. And I said: ‘Don’t you think Rhiannon is a beautiful name?’ And he said: ‘Yeah, it is a beautiful name.’”

True to its witchy beginnings, in time the song would reveal deeper significance. “I come to find out, after I’ve written the song, that in fact Rhiannon was the goddess of steeds, maker of birds,” Nicks explains. “Her three birds sang music, and when something was happening in war you would see Rhiannon come riding in on a horse.

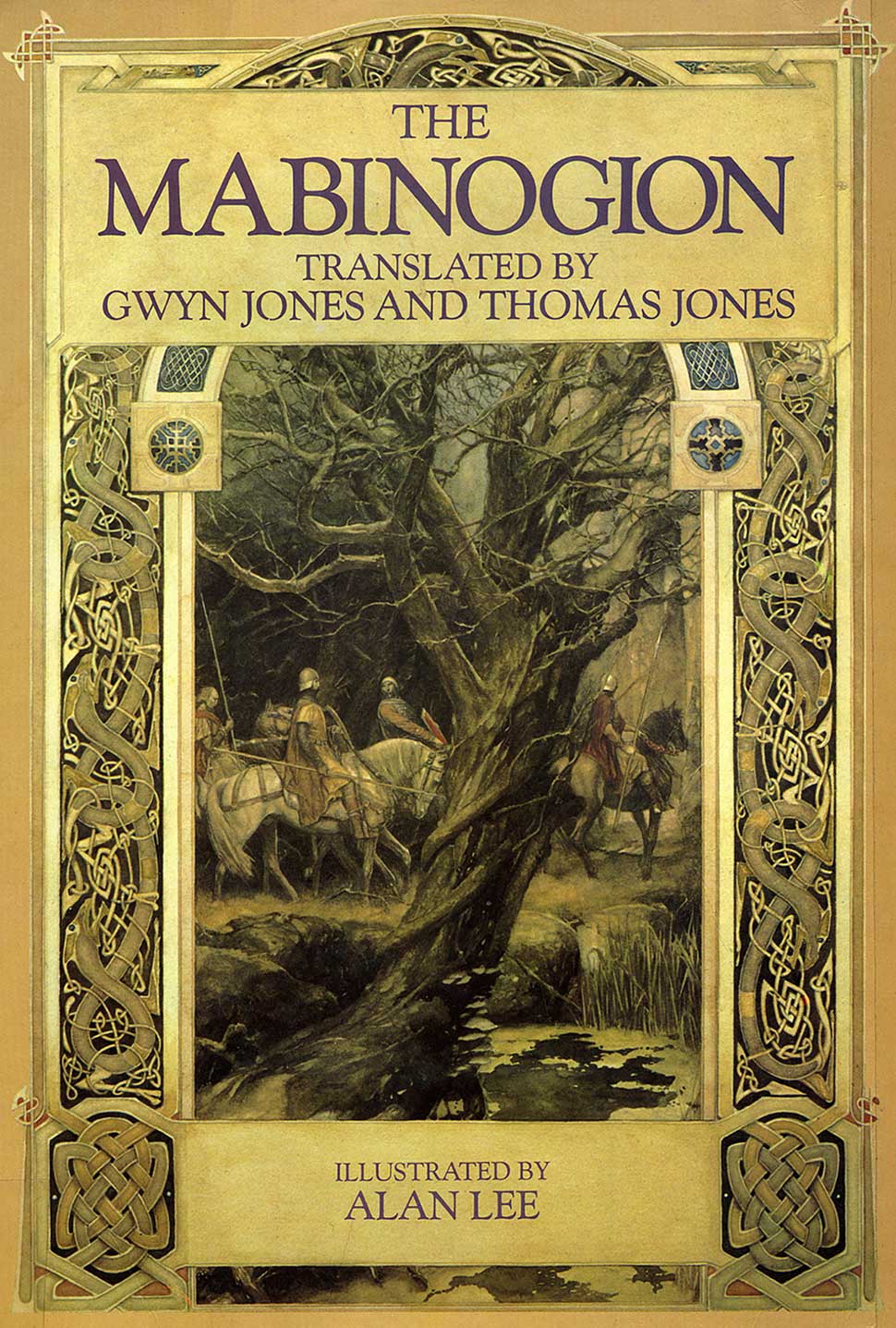

This is all in the Welsh translation of The Mabinogion, their book of mythology. When she came you’d kind of black out, then wake up and the danger would be gone, and you’d see the three birds flying off and you’d hear this little song. So there was, in fact, a song of Rhiannon. I had no idea about any of this.”

Nicks’s concerns in the autumn of 1974 were more down-to-earth. Working as a waitress, she was living with Buckingham, writing for the follow-up to the pair’s mostly ignored debut album, Buckingham-Nicks, and struggling to stay upbeat about her future.

Meanwhile, their producer, Keith Olsen, met Fleetwood Mac drummer Mick Fleetwood, who was looking for a replacement for the band’s guitarist, Bob Welch. Olsen played Fleetwood a few Buckingham-Nicks tracks. Fleetwood was impressed. Although he initially wanted Buckingham, and Olsen as a producer, Lindsey insisted it had to be a package deal that included Stevie.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“Who knows?” she says today. “It’s possible if that hadn’t happened that I would’ve gone back to school and never had a music career.”

Joining the rest of Fleetwood Mac in Sound City Studios in Los Angeles, the pair were nervous and excited about their new roles with the band. Of the magic moment when they first harmonised with Christine McVie, Mick Fleetwood later said there was an “undeniable sensation of rightness” about the vocal sound. “It was if Merlin himself could not have concocted a spell more perfect.”

And the spell extended to Rhiannon. With Buckingham’s finger-picked guitar line, an offbeat snaky groove from Fleetwood and bassist John McVie, and ethereal background vocals, Nicks’s raw piano demo magically came to life.

“What the band does, and have always done,” she says, “is take the skeleton of a song and flesh it out. They arrange right underneath my little skeleton.”

The self-titled album (also known as the White Album) that launched the most successful and enduring version of Fleetwood Mac was released in July 1975. Chosen as the second single, Rhiannon went to No.11 in the US but failed to catch on in the UK (when it was re-released two years later it reached No.46).

But the song’s significance went far beyond chart positions. It quickly became a live showcase for Nicks and a cornerstone of the band’s image and mythology. On stage, whirling with chiffon scarves, blonde hair tumbling out from beneath a top hat, Nicks would push the song to six minutes, building to a frenzy on the outro (‘Dreams unwind/Love’s a state of mind’) that Fleetwood said “was like an exorcism”.

“Rhiannon is a heavy-duty song to sing every night,” Nicks said in 1976. “On stage it’s really a mind tripper. Everybody, including me, is just blitzed by the end of it. And I put out so much in that song that I’m nearly down. There’s something to that song that touches people. I don’t know what it is but I’m really glad it happened.”

In the years since, Rhiannon has been covered by everyone from Waylon Jennings to Taylor Swift to countless American Idol hopefuls. And it remains a staple in the reunited Mac’s shows in 2015. Along the way, the strange magic from that bit of bibliomancy has continued to surprise Nicks.

“Years later, somebody sent me a set of four books written by a lady named Evangeline Walton,” she says. “She spent her whole life translating The Mabinogion and the story of Rhiannon. She lived in Tuscon. I went there in 1977, after Rhiannon had been a big huge hit. Her house was totally Rhiannon. She spent her whole life on the story. She never married. She had in essence almost become Rhiannon. And it was trippy.

“She had heard about the song. She told me about her life and how she had been entranced by the name, just like I had. It’s so interesting, because her last book was in 1974, and that’s right when I wrote Rhiannon. So it’s like her work ended and my work began.”

Bill DeMain is a correspondent for BBC Glasgow, a regular contributor to MOJO, Classic Rock and Mental Floss, and the author of six books, including the best-selling Sgt. Pepper At 50. He is also an acclaimed musician and songwriter who's written for artists including Marshall Crenshaw, Teddy Thompson and Kim Richey. His songs have appeared in TV shows such as Private Practice and Sons of Anarchy. In 2013, he started Walkin' Nashville, a music history tour that's been the #1 rated activity on Trip Advisor. An avid bird-watcher, he also makes bird cards and prints.