Christine McVie has a look of sultry invitation as she puts her hand on Lindsey Buckingham’s shoulder. She’s almost touching his tempestuous ex Stevie Nicks’ left hand, as Nicks puts her other hand in Buckingham’s and leans back in his arms to dance. Buckingham for his part looks a figure of glowering romance, the Heathcliff of Hollywood, dressed all in black, with black shadows encroaching on them all, as he gives McVie a reproachful look that stops short of rebuffing her.

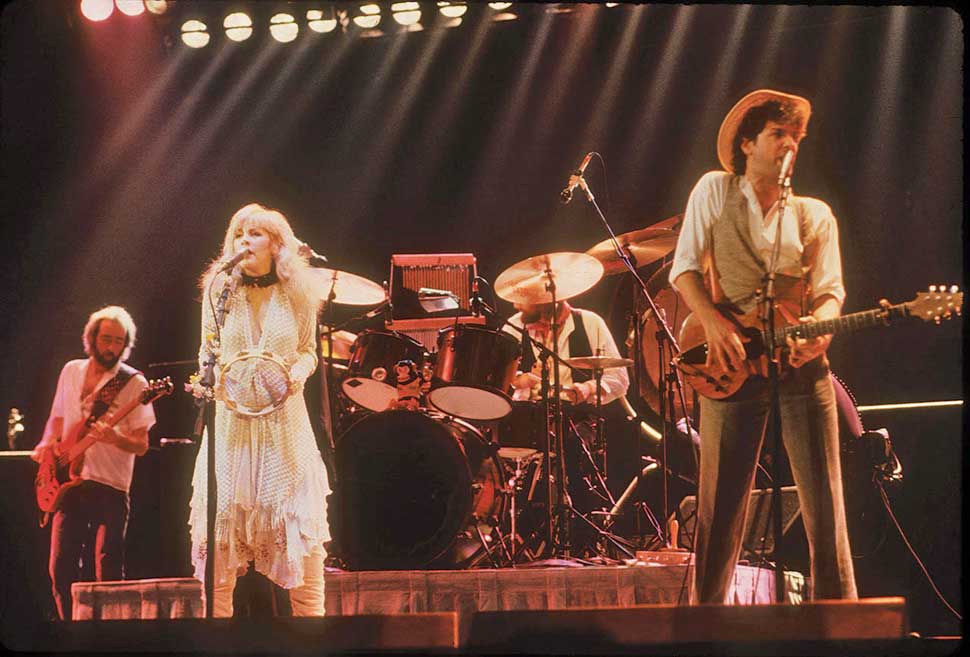

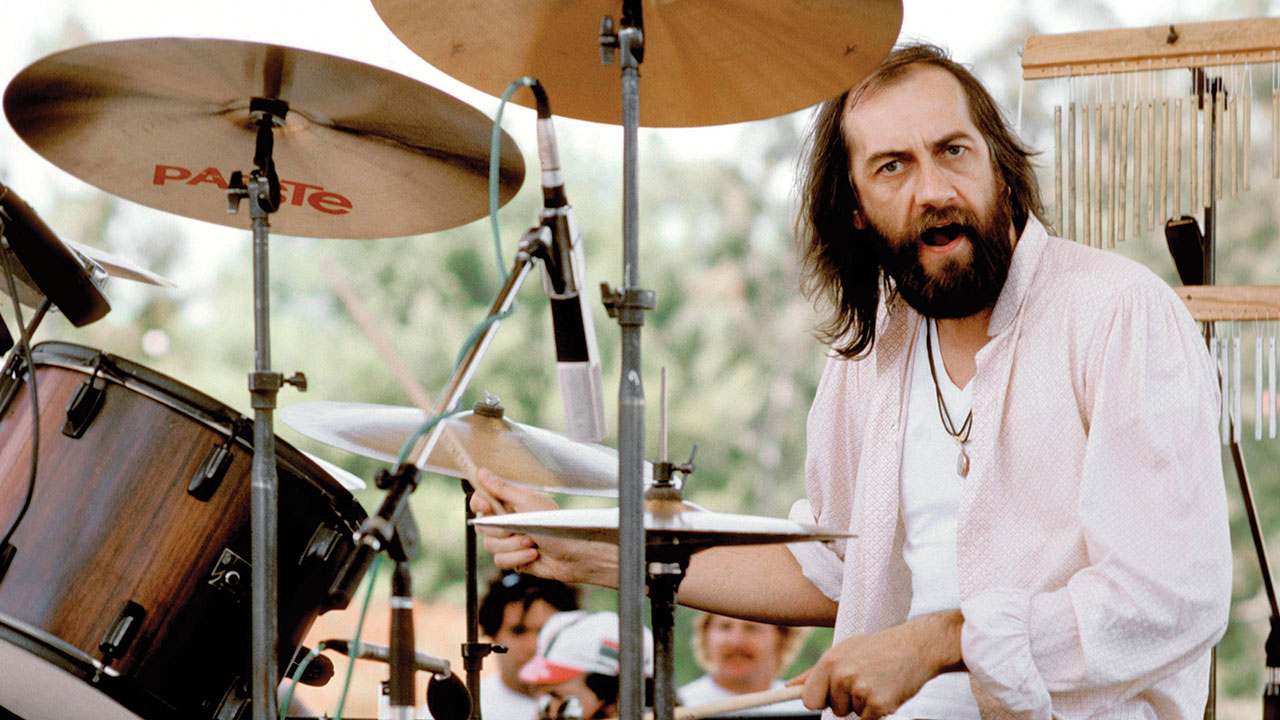

Mick Fleetwood and John McVie stand forlornly, looking out from the back of this sleeve photo for Mirage, the multimillion-selling Fleetwood Mac album most likely to have slipped your mind. But the message to potential buyers in 1982 was clear: step inside the Mac circus for more Rumours-style entanglements.

“Oh yes, exactly – that’s what it’s meant to do,” says Christine McVie. We’re sitting in a penthouse room in the west London offices of her band’s grateful long-time home, Warner. She’s wearing a grey mesh jacket and leopard-skin ankle boots, lived-in touches of glamour for a 73-year-old, still Brummie-accented rock queen not inclined to fuss. Holding the LP sleeve of Mirage’s outtake-heavy reissue, she considers her band’s real state back then.

“I’m trying to think of John [McVie] here,” she says. “John, I think, was still pretty much drinking like a fish. And he,” she says, finger pointing at Mick Fleetwood’s face, “was out of his brain. I’m sure I was drinking a lot of alcohol. I didn’t do any drugs then. He [Buckingham] was smoking marijuana. And Stevie was on… something or other. Everyone was doing something. But I can’t remember any nastiness on that record. It was quite an enjoyable experience. We goofed off a lot. And I don’t think there were any great romantic melodramas. Everyone was getting on great.”

Mirage was the studio follow-up to Tusk, Buckingham’s 1979 double-album production folly and masterpiece, itself the commercially underwhelming sequel to the 15-million-selling Rumours.

“I just went with the flow,” McVie says, when asked if she had misgivings about Tusk. “In the studio I said, ‘Whatever.’ And at that time, there was an awful lot of drugs and alcohol being consumed, and I’d just met Dennis Wilson from the Beach Boys, and I was going out with him and in love with him, and one thing led to another. And if Lindsey wanted to go into the bathroom and do drums on an empty Kleenex box, fine. Why not?”

Tusk had been backed up by a punishing tour schedule that provoked “the best and worst that anyone would ever see of Fleetwood Mac”, Fleetwood recalled in his autobiography, the band veering in later gigs from instinctive brilliance to exhausted carelessness as they ended the tour running on fumes.

“We’d just had two massive world tours after doing Tusk,” McVie confirms. “They had to scrape us off the plane after the last flight, and we all just dissipated and went away. I don’t quite know what I was doing. But Stevie did Bella Donna [a 10-million-selling solo smash]; Mick went to Ghana to make his The Visitor album.

"And I think we must have been under contract to do another record, and time was not on our side. And Mick thought about getting everyone away from their values and into a bubble, like we did in Sausalito when we made Rumours, to see if we could do something a little more Rumours-y, and not quite so left-of-centre as Tusk was.”

Led by Fleetwood – overextended on property purchases that would soon bankrupt him – and with bandmates asking where the money was after such huge tours (up their noses and on Lear jets, mostly), the band gave Buckingham an ultimatum before returning to work.

“We still want you to produce us,” Buckingham recalled them essentially saying, “but we don’t want to do that process any more.”

Buckingham’s own solo debut, Law And Order, hadn’t come close to Nicks’ success, so he buckled down gloomily to this new hair-shirt regime. Fleetwood Mac, he told a reporter, was getting “more and more like a day job”. “That’s what Lindsey said?” McVie laughs wryly. “Trust him.”

Did there seem an element of him clocking in on Mirage, the reluctant professional, after getting his way on Tusk?

“There’s always an element of that with him. ‘Gee, what-ever,’ you know. ‘O-kay…’ But then he gets sparked and excited about something. Like we were just doing a few songs a year ago in the studio, because we’re starting another album. And when you see the tears come into his eyes, you know it’s genuine. That he really is enjoying himself. I’ve never heard him say that [about a day job] – but as you say it, I can see it. Yeah, I’m sure a lot of it was quite pedestrian.”

So the tears weren’t coming much on Mirage? “No. I don’t think they were.”

Mick Feetwood's location for the out-of-the-way “bubble” where they’d record, not unconnected to minimising tax, was Le Château in Hérouville, France, the studio made famous by Elton John’s Honky Château.

“It was in the middle of nowhere”, McVie recalls. “I think Lindsey said, ‘Why fucking France?’ or words to that effect. Lindsey didn’t like being in France because he doesn’t like French food. He likes American food. Stevie saw a bit of romance to it. I remember her galloping in on horseback one day, in a velvet gown – I can’t remember why.”

Nicks also took the opportunity to have her hair done by five French hairdressers at once, while her and McVie’s Château lodgings were decorated to their specifications for the duration. “And rumour had it the place was haunted,” McVie continues, “which added to the fun. We all lived there, and we had a cook who lived in and fed us. But my memories of it aren’t that strong – probably because we were drinking a lot of French wine…”

McVie had only recently left Dennis Wilson, the once golden but now burnt-out Beach Boy who would drown while drunk on December 28, 1983, a year after Mirage’s release. His self-destruction had been too extreme for her to tolerate. Her love songs on Tusk and Mirage were based on their difficult, full-on months together.

“There’s a few songs about him, for sure,” she agrees. “Never Make Me Cry. Yeah, a lot of them are about Dennis.”

If the relationship was extreme, what parts of that extremity did she love?

“With Dennis? Oh, God,” she says. “He used to make me laugh. It’s not like he had this great, wacky sense of humour. It was the things he did that made me laugh. Yes, he was a thoroughly annoying human being, who was really bloody out of his brain with drugs. But there was something very endearing about him as well. And he had a big soul. A very, very hurt soul, but big. And a great capacity to write songs, when he was sober. Yeah, there was a sweet side to him when he came out of one of these weeks of debauchery – when he’d just be normal and sit on the couch with a cup of tea, and the smile, the real Dennis came through. There were some good times. But not many. The real Dennis didn’t come out that often.”

More typical was the time McVie returned to her LA home on her birthday and found her manic boyfriend had excavated a hole in her garden in the shape of a heart. “That’s true. I didn’t react very well. My gardeners didn’t, either. Especially when I got the bill!” She laughs heartily at the memory of Wilson’s foolishness now. “He had everybody standing around the edge of the heart, holding a candle, while sinking in the mud, waiting for me to come up so they could sing Happy Birthday. That didn’t go down too well.”

‘I’m out of my mind,’ McVie sings on one of her Mirage songs, Only Over You. Was she crazy in love for a while? “Oh yeah. I was addicted to him. It’s very easy to be addicted to someone like him, because people gravitated to him – you couldn’t help but like him. But he was just too far gone in the end. He lost it.”

Did she have to leave him for some of the reasons she left her ex-husband, bassist and bandmate John? “No,” she says firmly. “John was different. John didn’t have the same problems as Dennis. John wasn’t as loopy as Dennis. John just had a serious drink problem. And the fact we had to work together only multiplied the problem. So we were much better off being friends. And now we’re terrific friends.”

Riotous times with Wilson lay behind McVie’s songs, but Mirage’s general tone was all glistening, harpsichord-like keyboards, and a feeling of cool, gliding simplicity, a contrast with the jagged edges of Tusk. Buckingham slipped in a few experimental moments on the bustling New York tribute Empire State, and there are some gorgeous tunes, McVie’s album-bookending Love In Store and especially Wish You Were Here among them, while her Hold Me proved one of the band’s biggest hits. Nicks, too, chipped in with Gypsy, a tribute to her and Buckingham’s early, bohemian days together, which is Mirage’s most enduring song.

Outtakes on the recent reissue – including a cover of Fats Domino’s Blue Monday, the country gospel harmonies of Cool Water, and the Buckingham-written, McVie-sung European smash Oh Diane, which verges on doo-wop – show how far back Fleetwood Mac looked in their quest for simpler times.

“It was supposed to be Neil Sedaka-esque,” McVie says of Oh Diane’s vintage style. “And Lindsey’s always been a huge fan of the Kingston Trio. He loves all that stuff – folk, early Elvis songs, slap bass, the Everly Brothers. He loves the harmonies.”

Even on Mirage’s 1982 release, though, Buckingham made plain how much of this was done through gritted teeth, stating: “I was under pressure to regress.”

The album at least seemed to play to McVie’s songwriting and singing strengths of classically crafted, airy pop. “I don’t know how spontaneous that was, when I look back,” she says now. “We might have pieced certain songs together. I just remember an awful lot of laughter, and quite a lot of sitting around noodling. I don’t remember much frustration, or irritation. But at the same time I’m aware that this album feels more contrived.”

The lack of the intra-band tension that helped deliver both Rumours and Mirage’s 80s-conquering successor, Tango In The Night, may have lightened the studio mood, but it leaves thinner gruel for the listener. The desire to return to Rumours’ safe commercial waters, explicitly requested at Mirage’s start by Fleetwood, was ironically what has made it relatively sink without trace since.

“The pressure from Warner was to make an album,” McVie remembers. “And of course they’re all praying for another Rumours. And I think that might have been quite a self-conscious decision we made, that we ought to go for something un-Tusky. It’s pointing a finger towards Rumours – one finger.

“If I’m being honest with you, this is not top of my list of favourite Fleetwood Mac albums. It’s a fairly commercial album, with some quite good commercial songs. I don’t think we were trying to make them commercial. Or maybe we were – maybe that was the trouble. Where on Rumours, we weren’t trying to do anything except write. That has soul, that album. That’s what leaps out of the grooves. And I don’t believe this one has to the same extent. There’s some great craftsmanship, some great songs – but it pays Rumours homage.”

No one except Fleetwood could bear the idea of another shattering tour schedule in 1982, so after a month’s worth of dates, Fleetwood Mac left Mirage to its fate. It sold five million, around the same as Tusk.

Christine McVie, such a stabilising presence in Fleetwood Mac since joining from Chicken Shack in 1970 – even after Buckingham quit in disgust, having saved their creative bacon yet again on Tango In The Night – shocked her bandmates by announcing her retirement in 1998.

“I’d had enough of flying,” she says now. “I didn’t want to get on another plane. And I’d had enough of living out of a suitcase. I missed my roots. Because I’m a Cancer, you know. We’re domestic bodies. We like to cook, and we like our nests. And I was aching for my nest.

“My father had been ill and died, so I decided to move back to England. I bought a house that was in a terrible state, and repairing that really tickled my boat. And so, in the end, the band did a video called The Dance in ’97, and I went on a short tour with Lindsey back, and I said to everybody, ‘This is going to be it for me. I’m going to go home and spend some time with my remaining family.’

“It had to be England, close to my brother, just outside Canterbury. The green, green grass of home. And for a few years, it was fantastic – the dogs, the Aga. I was the quintessential retired country gal. But it wasn’t what I thought it was going to be.”

What did she miss? “Fleetwood Mac,” she says simply. “I made a solo album in my garage, with my nephew Dan, who’s quite an accomplished guitar player, and handy with Pro Tools. But Dan’s a fine artist, and he went back to his easels. And I started to become very isolated. I felt like I was rattling around this huge house on my own, not doing anything. And I became quite unwell, so I thought, ‘I’ve got to do something about this. I’ve got to find a way of getting on a plane again.’”

She sought out a therapist for help.

“This guy said to me, ‘Where would you most like to go?’ And I’d always been in touch with Mick. He always reached out and asked how I was. And Mick lives in Maui, so that’s what I said.”

Fleetwood ended up offering to fly there with her from London. “I didn’t even notice the plane leaving the ground. And Mick has a little blues band in Maui, and I did a couple of songs in his gigs over there. That was scary. But the big stage with the big Mac, and those four familiar faces looking at me – and all the guys, because it’s the same crew – just felt like being home. I get goosebumps even when I think of that first time.”

So having thought she’d gone back to her roots, did McVie find stadium stages were the real home she’d missed?

“Yeah. What’s remarkable is it seems we’re more popular now than before. Because I think it’s the five back together, and one element was missing all those years. And everybody accepts that fact now. It’s that five. It’s the synergy.”

Like McVie’s Kentish sojourn, Mirage was when Fleetwood Mac tried to retreat to a falsely comforting idea of home. Instead, it taught them that you can’t go back to where you were before, or make a Rumours deliberately.

“It’s the one that got away in people’s memories – I think even ours, to a degree. There’s some really good tracks,” she says, looking again at that cover that tries so hard to make you think of Rumours. “But there a song on here called Can’t Go Back.”

She murmurs the tune to herself, then recalls the words. “‘Standin’ in the shadows/The man I used to be/I wanna go back/Can’t go back, can’t go back.’ That says something about some of the things we’ve been talking about.”