In progressive terms, Canada hasn’t only been ruled by Rush, although that band are without a doubt the figureheads of all things pomp and prog-like to have emanated from the Great White North.

The latter half of the 70s saw the rise of similar bands, such as Saga, Zon, Max Webster and Prism, to name a few, who mixed the progressive flourishes of the 70s greats with something more commercially minded, as one might have expected from Styx or Kansas.

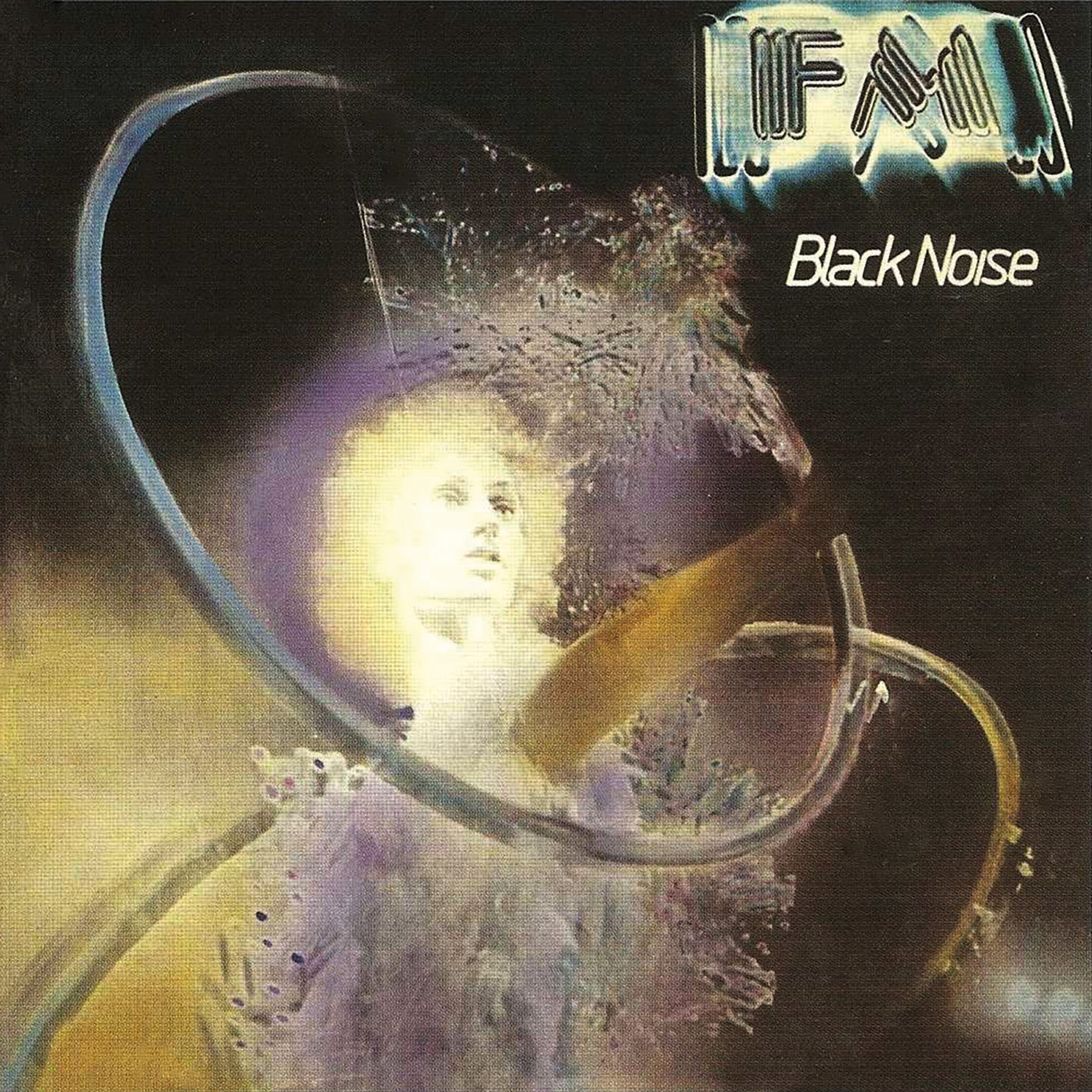

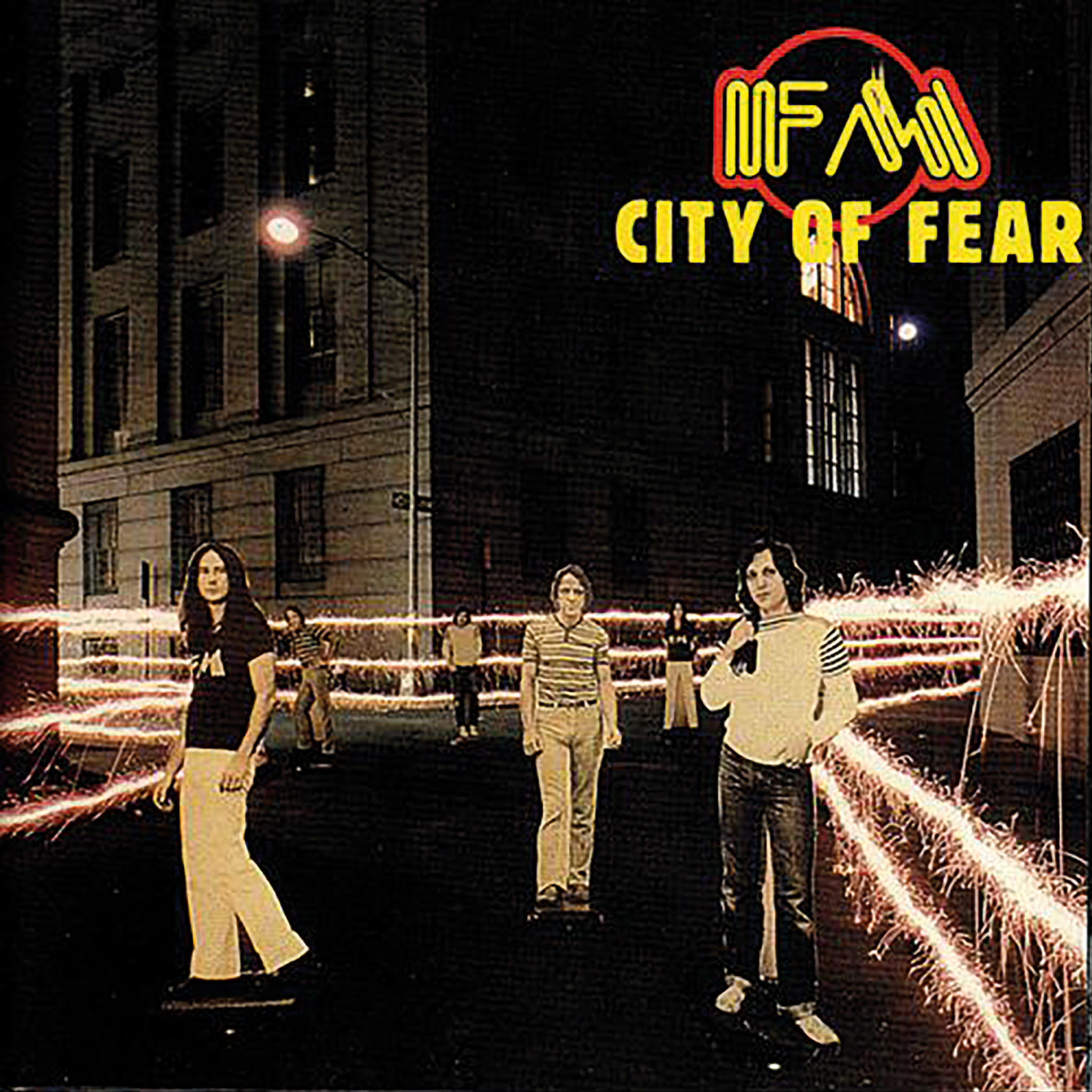

One of the best, however, was FM, who formed in Toronto in 1976, and for at least the next half decade were one of the prime exponents of Canada’s pomp sound, thanks to albums such as Black Noise (1977) and City Of Fear (1980).

However, it’s taken the cult Canadians almost 30 years to release their latest studio album, Transformation. It follows a flurry of activity that started when their set at NEARfest 2006 was released as a CD/DVD set in 2014, and their first four albums were remastered for CD for Esoteric in the UK. Bandleader Cameron Hawkins (vocals/keys/bass) explains why the time was right for new material.

There’s constantly new music coming through, so we thought we had nothing to lose by doing an open and honest, serious prog record.

“In FM’s history, there have always been things that bring us together and then drive us apart. There was no FM for quite a number of years, but that’s not unusual for us. I was happy doing other things involving the creative application of technology. The skills you learn in being a bandleader are also useful in business for interacting with people and coming up with ideas; they’re all transferable.

“Then I turned 60 and I believed I had another album in me, but I wasn’t really thinking about an FM band thing. It slowly began to dawn on me that FM was more than just me, and that’s actually what I liked about it. By finding other guys to join me – the original guys were either all over the world, or dead – it became another part of the FM legacy.

“I called Paul DeLong (drums) and his answer was: ‘What took you so long?’” Hawkins says. “So, five years ago we started working together on songs, and then we added Aaron Solomon on violin about three years ago. We would send tracks to each other, add to them and send them back. But then Aaron had to take a leave of absence to appear in some plays around Ontario – he’s also an actor – so Ed Bernard came in on mandolin and viola. It wasn’t until we did the band photo that we were all in the same room together.”

While it’s usually easy to find guitarists, drummers and the like, you’d expect it to be a bit more problematical to track down violin, viola and mandolin players. Not in Toronto, it seems. “Ed is a great guitar player and plays in a band called Druckfarben,” says Hawkins. “I didn’t realise until later that he’s a great violinist and also plays mandolin. He’d seen FM when he was about 11 so we were very lucky to find him.”

The band’s 1977 debut album Black Noise is still generally regarded as their best, but in the finest traditions of experimental bands, they’ve refused to repeat its space rock style. “You don’t want to be typecast by the past – you just have to let flow whatever comes out of you,” Hawkins says. “We knew that Transformation’s prog count would have to be ridiculously high and it had to be a commercial suicide record!

“That’s the great thing – the prog community is hanging together more than ever today, not just listening to old stuff. There’s constantly new music coming through, so we thought we had nothing to lose by doing an open and honest, serious prog record.”

The methods may have changed but Hawkins is grateful for the simpler recording techniques of the modern age. “The same computer you do your taxes on can be used to create music and art. The technology is already there in our hands and any time you get inspiration, the tools are there. It usually starts with Paul and I, with a driving bassline and a complex drum pattern. Then we’d add a keyboard and put a mandolin or a violin over it.

“We tried not to get too deep into the song before everyone had their chance to put their own ideas into it, and then it fell to me to move things around and structure it into an FM song. We have unwritten rules – they’re mostly between five and eight minutes long and they start off more like movements, but there are always melodies that I hum on top of it.

“The hardest part is to find the lyrics, so the last thing is always, ‘What do you want to say that goes with what the music says?’ That’s always hard for me to dig that out, but Transformation is just like any other FM record in that respect. Thank goodness we had six years to do it!”

We knew that Transformation’s prog count would have to be ridiculously high and it had to be a commercial suicide record!

Today Hawkins remains the only ever-present member of the band. “FM has certainly been a frustrating band to be in,” concedes the softly spoken Torontonian. “I don’t think that makes us special or unusual. We have a unique style and that’s certainly made keeping a stable line‑up a lot harder for us, but I don’t think the music would have been as good without that struggle. Almost every record company we were with went bankrupt, and musicians really need to get paid.

“It’s hard to keep a band going when you’re not being rewarded for your success, and that leads to people leaving. If one guy wants to have a family, you can’t have a family and be in FM – they would starve!

“And then there’s Nash The Slash!” Cameron smiles wistfully when mentioning his co-experimentalist, famous for never appearing without bandages covering his face, who sadly passed away in 2014. “There was a man who could contribute great things and then walk away from them, again and again. As the news of his passing sank in, I realised that my musical career would have been a lot different if I’d never met him. I’m proud of the music we made together on Black Noise, and later on Con‑Test and Tonight, but mostly of the gigs we played, upwards of 200 gigs a year across Canada. The reviews were generally great but he continually walked away from that and couldn’t reconcile himself to it.

“FM was a good band so who knows how much better it would have become if he’d stayed? He was a very complex, very gifted man who could get very enthusiastic about something and then go very cold on it, which isn’t helpful for anyone else who’s depending on him. That was the baggage that came with him, but if you continually do that, you don’t get as much of a sense of fulfilment about what you’ve done.

“What he did wasn’t logical, but that was just him. It all comes down to the financial thing – if you’re really successful, I’m sure your level of tolerance for people goes up, and maybe your commitment to things goes up too. I’ll never find out!”

Nash was replaced by violinist and mandolinist Ben Mink, another mercurial talent who stuck around for a few albums before going on to be a successful writer, performer and producer, as well as playing on Rush’s Losing It from the Signals album.

“Ben’s a completely different person. He’s a really gifted musician like Nash, but here’s a guy who played differently every night, depending how he felt. Nash and I were road players – 80 per cent of it was identical every night and 20 per cent was how you presented it and stuff that happens onstage. Ben was so gifted that he could do it his way every night and make it work. I’m really lucky I played with both those guys.”

The sticky subject of live shows with the current line-up comes up, especially as Hawkins is now without any other original members since drummer Martin Deller relocated to Copenhagen. “We’ve been in rehearsals, we’re playing the record together and slowly adding the old FM stuff to it,” he says hopefully. “We have to learn how to play together because none of us were together when we made the album. We’ll need a couple more months of occasional rehearsal and then we’ll have a good 90 minutes’ worth. I believe we’ll be as good as we ever were, maybe even better! We’ll do a showcase here in Toronto and then see what happens – you can’t call in deposits for concerts until you prove yourself.

“I learned a lot of things in the business world and one of those is to keep one thing that you’re working on important in your mind. Don’t ignore everything else, but don’t lose sight of that one thing, and playing an hour and a half of FM music is that one thing. That will hopefully lead to more gigs. Maybe we’ll go down to the States and see if anyone remembers us, and maybe we’ll come over and play in Europe, which we’ve never done.”

The live album and reissues of Black Noise, Direct To Disc, Surveillance and City Of Fear on Esoteric were a surprise bonus in 2013. Cameron explains: “I thought the ideal thing would be to get them out and then do something new. It was a six-album distribution deal, where the last piece of the puzzle was the most difficult one. Certainly working with Esoteric has been great. I looked on their website and it was like Soft Machine, Arthur Brown – we belonged with this company because all our childhood heroes were there.”

The reissues were particularly tricky to do because all the original masters had been lost. Black Noise was owned by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, their equivalent of the BBC. “They put it on their shelf and somebody stole it,” says Hawkins incredulously. “There’s actually a quad mix somewhere with synthesizers flying around in circles around your head, but that’s gone too. Maybe it’ll show up one day. FM music is still available on Amazon but we’ve never received any royalties. If I was bitter enough, I would track them down, but I much prefer to dwell on the positives and the future.”

In 1981, the highlight of FM’s career was opening for Rush on their North American Moving Pictures tour. “Talk about rock’n’roll zoo!” laughs Hawkins. “At Madison Square Garden, the Ringling Brothers Circus pulled out of the main arena and then Rush came in. You’re walking in and there’s dwarves and elephants and white tigers – we were in fairyland. Then you walk out and play for 17,000 people who immediately react 100 per cent positively, and I suddenly thought: ‘I have long hair and a Rickenbacker bass and I’m playing keyboards – maybe they think we’re Rush?’

“Something amazing happened throughout the whole tour – our crew and their crew, our band and their band, and their audience… it was magical. We’d do our soundcheck and then the cover would come off Neil’s drums, Geddy would come over and pick up a bass, Alex would plug into his amp behind Ben and we’d just start playing together. It was a wonderful thing.”

The big question, though, is this: has Transformation been a pleasant enough experience for Cameron to continue making music? He pauses for thought before saying: “It’s definitely been positive but I’ll just take it slowly. If we could play some gigs, that would be good, and maybe the music will come through again. We’ve just emptied ourselves. The music’s in there but it has to want to come out.”

Transformation is out now on Esoteric Antenna. Visit FM online for more information.

Recommended Listening

Black Noise (1977)

FM’s impressive debut album set the standard against which the others are judged. Their unique format – Cameron Hawkins’ spacey synths, expressive bass and smooth vocals; Martin Deller’s busy percussion; and the enigmatic Nash The Slash on violin, electric mandolin and rawer vocal – is unusual but interesting. Sci-fi themes abound in the dark title track, Journey’s upbeat groove and the aggressive instrumental Slaughter In Robot Village, but it was the US radio hit Phasors On Stun that would best marry their echoey instrumentation and crazy rhythms with a pop sensibility, one that would endure throughout the following decades.

City Of Fear (1980)

By album number four – their third with future kd Lang/Heart/Geddy Lee producer Ben Mink on violin and electric mandolin – they’d dropped space rock for a sparser, angrier sound based around Mink’s distorted mandolin. Produced by electronic pioneer Larry Fast (Synergy/Peter Gabriel), the stark soundscapes of Krakow, the catchy Power and the soaring Surface To Air are among the highlights. The mandolin could almost be a guitar on the rocking Riding The Thunder, while Nobody At All is the closest they ever got to a heartfelt ballad, with Mink’s beautiful violin showing exactly why he would soon guest on Rush’s Losing It.

Transformation (2015)

Organic but no less eclectic, Cameron Hawkins and the new four-piece line-up delivered a different sound for the band. The multi-layered opener Brave New Worlds, the commercial Reboot, Re-awaken and orchestral Safe And Sound all add quality to the legacy, along with other quirky songs that make up a bold but also pleasingly familiar release. Ed Bernard’s viola adds a melancholy tone to a complex record that proves to be one of their most dramatic statements.