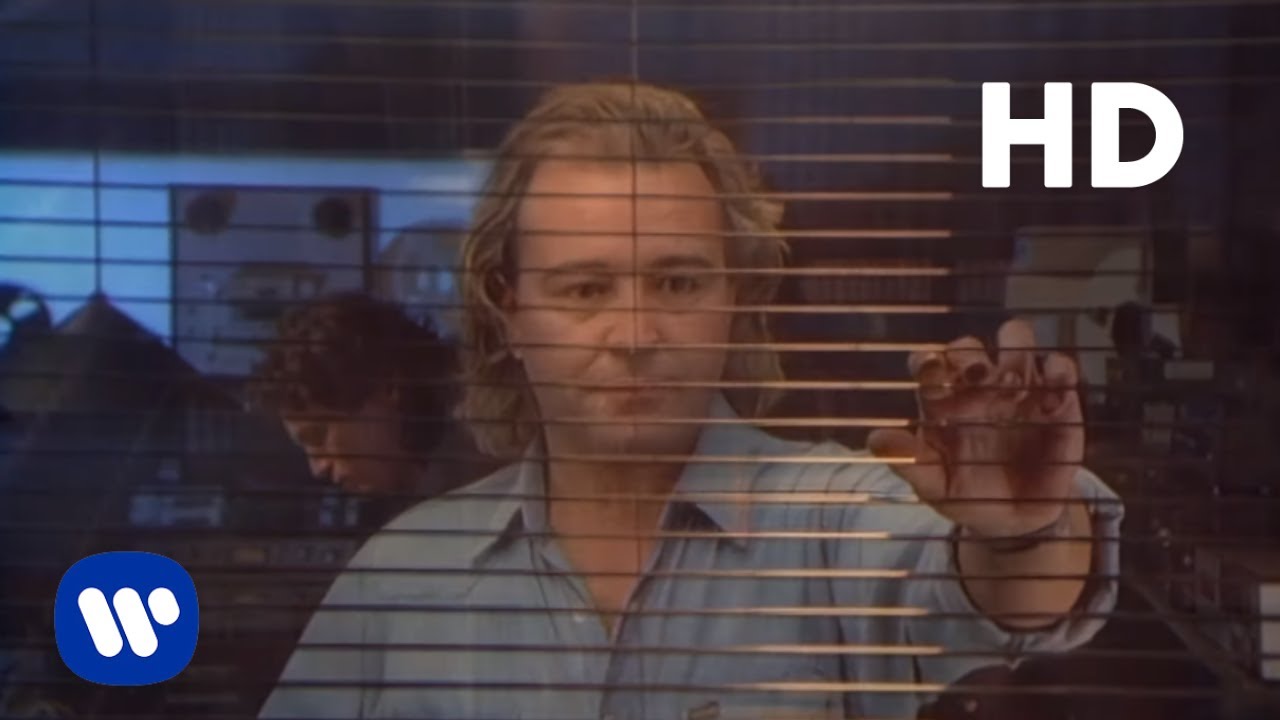

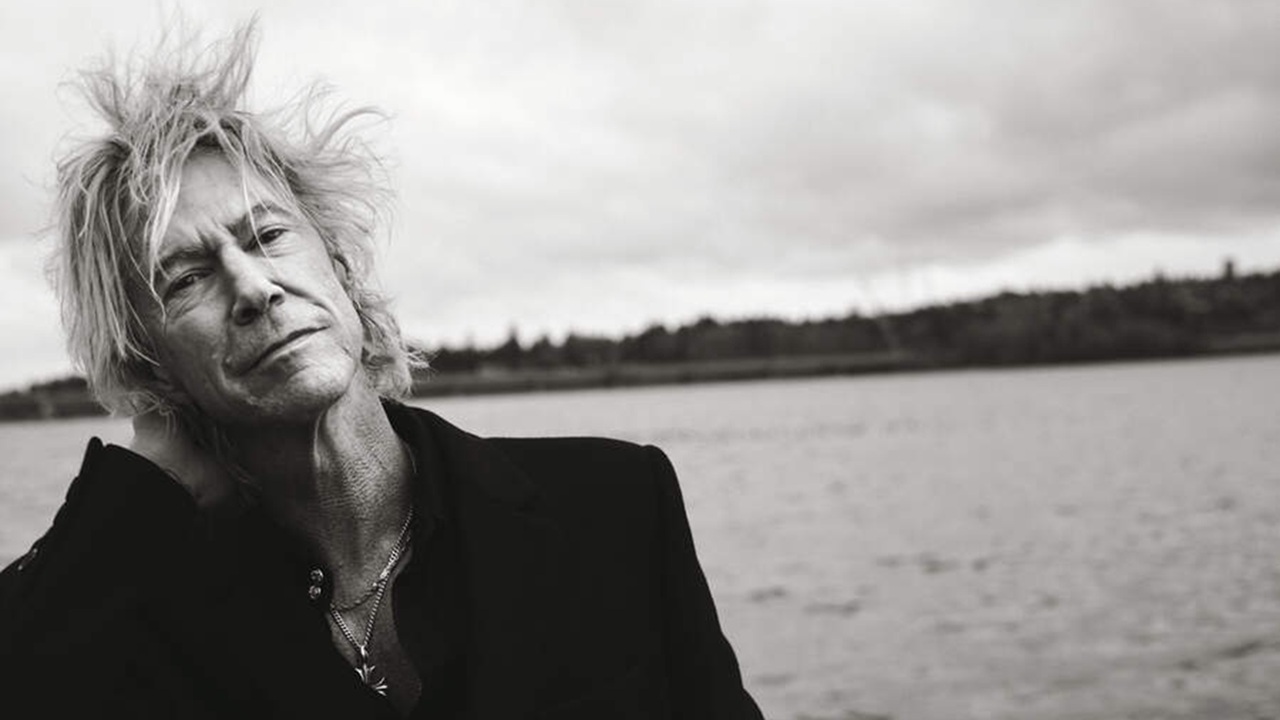

"The Boston Symphony hasn't changed its name, so why should Foreigner?": Mick Jones looks back on 50 often fractious years with one of rock's most successful bands

Mick Jones steered Foreigner to instant success, but with a self-confessed "bit of a control freak" at the helm it was often far from plain sailing

In the speech he sent along with his daughter Annabelle to Foreigner’s belated induction into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame, Mick Jones described his band’s near-50-year journey as an odyssey. That notion was hardly dispelled by the optics and brouhaha attending the HOF bash in Cleveland on October 19.

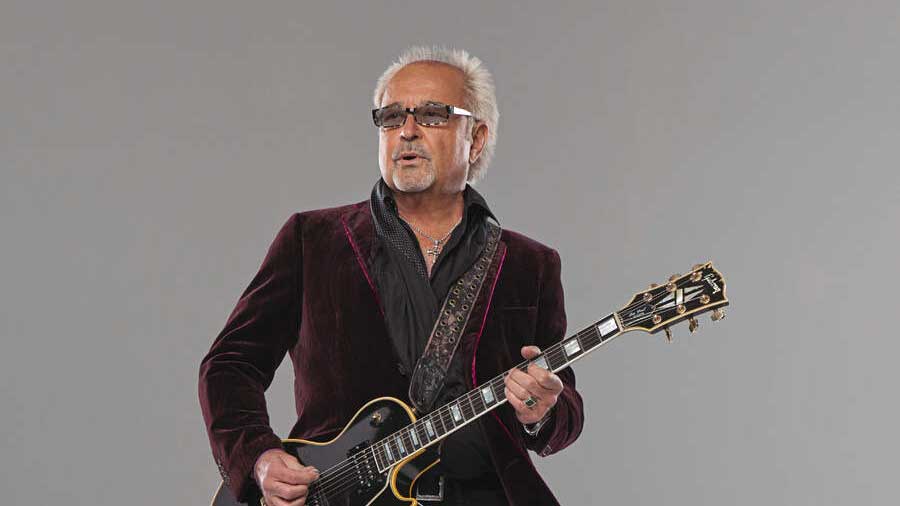

Just two original members made it along on the night: former frontman Lou Gramm and ex-keyboard player Al Greenwood. They were joined by former bassist Rick Wills, a 1979 replacement for the late Ed Gagliardi. Like Gagliardi, multi-instrumentalist Ian McDonald is no longer with us.

Jones, who’d announced his Parkinson’s diagnosis the previous February, excused himself. Which left drummer Dennis Elliott to deliver the slice of rancour all too familiar to Foreigner watchers through the decades. In a post on Facebook two nights ahead of the ceremony, Elliott let rip: “We were finally given the schedule last night, and it’s not to our satisfaction. So we are staying home.”

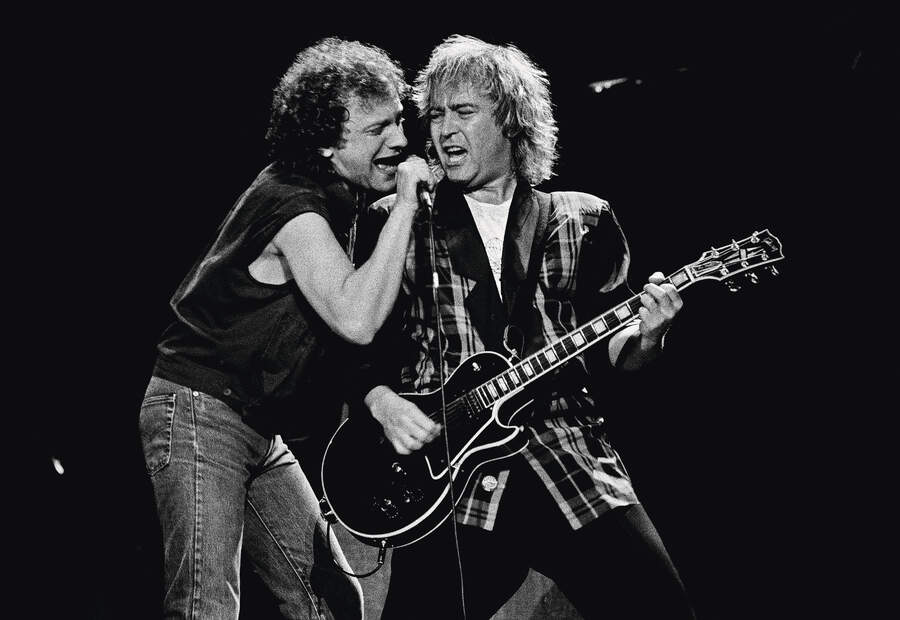

It was ever thus with Foreigner. Formed in New York in 1976 by expat Englishman Jones and called Trigger to begin with, the group was initially split equally with three Brits and three Americans. Parity between them was otherwise lacking. Jones ruled the roost – a “bit of a control freak”, in his own words; a domineering taskmaster with a temper, and worse, in Gramm’s. Under Jones’s iron hand, and with Gramm’s stellar voice, they blasted off with the five-million-selling debut album Foreigner, and and launched an even more successful follow-up with 1978’s Double Vision.

Gagliardi got his marching orders prior to 1979’s undercooked Hot Blooded. That record’s relative failure prompted the defenestrating of McDonald and Greenwood by Jones and Gramm. The came 4, Foreigner’s commercial and creative zenith, melodic rock gold mined from the combustible alliance of Jones, Gramm and uber-producer Mutt Lange.

Then in 1984 one last show of strength, I Want To Know What Love Is, the power ballad to end all power ballads. Its parent album, Agent Provocateur, was a mess. In its aftermath, Jones and Gramm bickered and ultimately split from each other. But Foreigner have forged on. Unbowed these past 40 years and still a going concern, in spite of not having made a record together since 2009’s so-so Can’t Slow Down and a complete absence of original members from their current line-up.

For all intents and purposes retired, Jones doesn’t do interviews these days. He’s made an exception to talk to Classic Rock, for this one, conducted over email from his home in New York, and perhaps his last word on his altogether remarkable band.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

What does the upcoming Hall Of Fame induction mean to you personally? And why do you think it took so long in coming?

Well, it’s nice to be recognised by your peers. All the great artists that have been entered over the years into the Hall Of Fame makes it an honour for me to be inducted. In answer to why it took so long, I really haven’t thought about that. In fact it might mean more to me now than if it had happened twenty years ago.

Let’s go back to the beginning, and the start of 1976. Where were you at?

I was playing and writing songs with the Leslie West Band. After I left, I began writing songs for myself. During one of my writing sessions I came up with an opening riff on the guitar that I thought was pretty catchy, and that became Feels Like The First Time. I recorded a demo of it, and upon hearing it I knew instinctively that it could possibly be a hit. Now I had to form a band that would be able to bring the song to life.

How did that lead into Foreigner?

Once I had Feels Like The First Time in my pocket, along with a few other songs, I wanted to put together a group of musicians who could play and form a chemistry in the studio and on stage. That was really important to me. Because bands can sound great in the studio, but that doesn’t mean it automatically translates to the stage. I deeply wanted both.

I’d known Ian McDonald from his days with King Crimson. Ian had plenty of on-stage experience. He could be quite eccentric, and he became an important part of Foreigner. I invited Dennis Elliott, who had been playing with Ian Hunter. Ed Gagliardi and Al Greenwood joined next.

Then there was one more important ingredient, and that was the excellent Lou Gramm. I had gotten a copy of the Black Sheep album, which was the band Lou was fronting. I was really impressed with his vocal timbre and phrasing. I later heard him live, and that nailed it for me. I knew Lou had what it took to bring out the best in the songs I had written.

What was the musical blueprint for the band you had in mind?

I didn’t exactly have a blueprint in mind, but I had an inkling of what I was looking for. The sound came out of the cultural backgrounds of the Brits and Americans that made up Foreigner. Our musical sensibilities meshed well together. I like to think it had a freshness or an energy that stood out at the time. I think the success of the band supports that.

What qualities do you think are essential to being a good band leader?

I think most aspiring musicians have a vision of how they want their music projected to the audience. For that vision to take off, you need to be able to communicate your desires to the rest of the band, so they know the direction you want them to go in. You also need to be able to balance all the personalities within the band. Keep the egos in check.

Foreigner had such huge, and instant, success.

It was a kind of a tsunami, and staying with our heads above water was not always easy. We had to really take the time to gather ourselves and remain grounded. It had its difficulties – dealing with the industry, the media attention, and being there for our families. It was a real juggling act.

There was just 15 months between the band’s first album, Foreigner, and follow-up Double Vision.

I wanted to keep the momentum going from the first album. It was a lot of work within a short period of time and it led to feeling a little burnt out. But it was a case of striking while the iron was hot.

Ed Gagliardi was replaced after that album. What led to his departure?

With the direction the band was going in, Ed just didn’t quite fit. We were a mainstream rock band, and Ed was slanting more into a progressive rock sound in his playing. It was a very difficult decision to let him go.

How do you look back on the next album, Head Games?

When you experience the type of success we’d had up to then, you fall into the trap of letting it inflate your ego. You count the gold albums hanging on your wall. It’s a type of reality outside the norm of day-to-day living, and it can cloud your perceptions.

Following on from that third record, both Al Greenwood and Ian McDonald also departed. Any regrets?

Of course. You’re in the studio and touring with these guys who also are your friends. It’s like a second family, and can become divided, which was the case with Al and Ian. They were getting frustrated because of their level of participation in the writing. And quite rightly so. I was a bit of a control freak about the direction I wanted to take the band in, which alienated them both. That is a regret.

Mutt Lange is hardly renowned as easygoing as a producer. How did the two of you go together to make 4?

Mutt and I shared the same vision, which was to create a memorable album of really good songs. I wouldn’t say we weren’t ruthless, but we were equal in driving the musicians to carry out our vision. Both of us were very headstrong in the studio, but I found that to be very positive because we pushed each other to be at our best. We got on very well and I think that shows in the quality of 4. We developed a strong respect for each other.

Agent Provocateur was a troubled record. Fair comment?

Touring 4 was very self-indulgent. Staying in the most expensive hotels, living the high life. No TVs flying out of hotel windows, just lots of money. You can lose focus when you’re experiencing that type of success. You’re also constantly worried about staying relevant. The pressure can sometimes sideswipe you. You think you’re going to lose it all. Every album in-the-making has its challenges.

It was an album where we started writing and experimenting in the studio. We began in New York, with Trevor Horn producing. Then the project was shifted to London. Trevor’s focus wasn’t aligned with mine and things went awry. We ended up hiring Alex Sadkin, who was producing a Thompson Twins album at the time. The hardest thing to do was keep everyone focused. There were always last-minute changes to the tracks, which led to frustration among the band members. We got it done, but it wasn’t easy.

What was the catalyst for the breakdown of your relationship with singer Lou Gramm?

It happened so long ago, and to dredge up those memories now serves nobody. I like to think it’s in the past. Hopefully Lou feels the same way.

You went off to produce Van Halen’s 5150, their first album of the post-David Lee Roth era. What were you able to bring to another band?

When you’ve accrued as much experience as I did when making all the Foreigner albums, you’re able to foresee problems and avoid things that can lead to chaos in the studio. That came through for me working with Van Halen. I was able to bring together their creative energies into a very good album.

But not so with Foreigner’s next record, Inside Information.

It’s amazing that record even got made. Things had changed between Lou and me. He’d half moved on emotionally and was not happy singing ballads, although there were some rocking songs on the album. It wasn’t very collaborative in the studio. Lou came in, sang the songs, and then left as soon as he could. Due to those circumstances it wasn’t a very good record.

If you could go back would you do anything differently?

Looking back, I was so driven to get everything right that I may have made band members feel in some ways excluded from the creative direction of the group. I was a bit of a perfectionist in the studio. I may have come off as being controlling. I could’ve been a little more flexible with the guys. But then again, would Foreigner have been as successful? That, I guess, we’ll never know.

Having started out in 1976, Foreigner have had a long career and many peaks and troughs. What’s kept the band going for all those years?

The songs. The last time I performed with the band was two years ago, and due to my struggle with Parkinson’s. I’m doing okay.

There’s been criticism that Foreigner is now just a cover band.

I find that a bit over-the-top. The current line-up has been together for a long time. And, you know, over the years major orchestras experience changes in personnel either because musicians retire or pass away. The orchestras continue to perform the great music of the past. The Boston Symphony hasn’t changed its name, so why should Foreigner? People still want to hear the music played live.

Which would you say is your greatest song?

If I base my opinion on worldwide popularity, I’d have to say I Want To Know What Love Is. It has become a kind of anthem.

And what’s your single biggest regret?

Regret is a part of the human experience. I do sometimes think about all the time I spent apart from my family due to all the touring. I like to think I’ve been a good father to my children, but it must have been difficult for them to not have their dad at their side all the time. My children are great, and I love them dearly, but it hasn’t always been easy for them.

What’s next for you? Just living my life to the fullest.

As I’ve gotten older, I look back at all the amazing years I’ve had in music and the wonderful memories. I’ve been very fortunate as an artist. Knowing I’ve brought joy to so many people, that means a tremendous amount to me. One never truly knows what the future holds, but I do know that I want to take advantage of my remaining years.

Paul Rees been a professional writer and journalist for more than 20 years. He was Editor-in-Chief of the music magazines Q and Kerrang! for a total of 13 years and during that period interviewed everyone from Sir Paul McCartney, Madonna and Bruce Springsteen to Noel Gallagher, Adele and Take That. His work has also been published in the Sunday Times, the Telegraph, the Independent, the Evening Standard, the Sunday Express, Classic Rock, Outdoor Fitness, When Saturday Comes and a range of international periodicals.