It was easy to spot the rock fans in This Is England ’90: they were the two fucknuts in mirrored shades and pencil moustaches who didn’t know anything about drugs and ruined the underwhelming first episode with their ‘hilarious’ ‘sniff-banging’ antics. By the final episode they were enthusiastically dry humping a woman old enough to be their mum.

Higgy and Flip are clueless, sneaky and styleless – it’s not their fault, they’re just written that way, like the writers looked at old YouTube clips and decided that Paul Calf was a bonafide youth movement. Their only purpose is to illustrate the naff old world: those daft old rockers, they don’t realise the tide is changing, still dressing and talking like they’re in a naff 80s cop show, too busy listening to Huey Lewis to really get the news, man.

This is really not how I remember it. For starters, there’s the drugs thing. Back then, before rave culture really hit, if you wanted drugs you asked rock fans. Metalheads usually. If you wanted “a bit of Pat Cash”, you followed the smell of patchouli oil and Embassy Regal and went to a Black Sabbath fan. As a non-smoker, a Bob Dylan fanatic turned me on to the joys of hot-kniving. I laughed hysterically as he did daft things with a bowl of sugar for half an hour. Yay, let’s hear it for drugs!

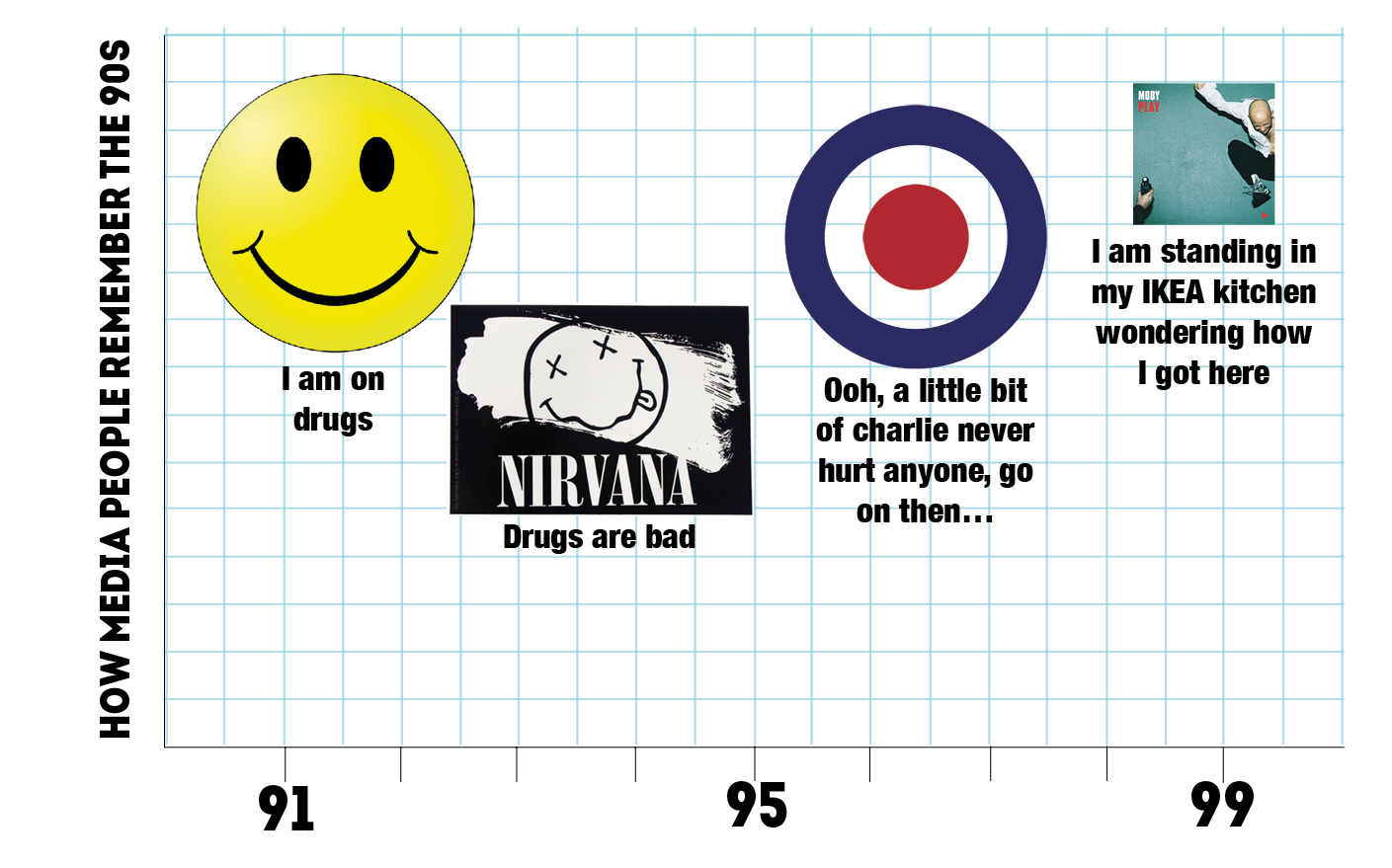

They’re re-writing musical history before our eyes. As soon as The Guardian got a sniff about This Is England 90 it had a raft of pieces commissioned about how awesome acid house was, Oasis Vs Blur and Cool Britannia – a whole decade reduced to some pictures of dudes in bucket hats and dungarees and Noel shaking Blair’s hand.

Here’s how the media remembers the music of the 90s:

I saw Happy Mondays at the Glasgow Barrowlands in 1989. They’d been booked to play Strathclyde Student Union but it had sold out fast and upgraded to the Barras. In many ways it was an ordinary gig. It had that ‘right-time-right-place’ buzz you get watching a band that’s on the rise – but still, it was just a gig, full of rock fans drinking lager and smoking.

There were some differences: 1) They only played just eight songs, though each one was stretched out into looping, meandering jams. 2) Shaun Ryder spent most of the set sitting on the drum riser. 3) A lot of the audience weren’t facing the stage – to be fair, apart from Bez’s bulging eyeballs there wasn’t much to look at – but at each other. People were dancing.

Regardless, Madchester didn’t sweep across the country like a revolution. Hardcore techno and pills did. Within a few years, the music scene in Glasgow had changed. By then I was writing for M8, a Scottish music magazine that was slowly transforming itself into a rave mag, much to the disgust of most of its writers. I was sent to review The Orb and took a couple of mates. Outside the Barrowlands, people were offering ‘Strawberries’ for tickets. Inside, we were the only people at the bar. The Orb’s ponderous take on Vangelis-style atmospherics went right over our heads. But then we were half-cut on Tennents, not ripped to the tits on ecstasy. The people who *were* jumped around like excited toddlers every time a beat kicked in, which wasn’t very often. We sat in the “chill-out” room downstairs nursing a pint and wondering what the fuck was going on.

For years afterwards, if you were unlucky enough to end up in a Glasgow nightclub, you felt the difference. For all the media’s big claims that we were in the grip of a new musical revolution, the music didn’t really change too much – it was still shite – but now you could easily be the only person at the bar not ordering water or Redbull.

On a weekend trip home me and a mate were asked if we had any ecstasy by an 11 year old girl in a pool hall in Saltcoats. At night we went to the Metropolis. The Metro had once been a cinema – when I was 11, I saw ET there – by 1990 it had been transformed into Ned Heaven: Sodom and Gomorroah for teeth-grinding pill-gobblers in sweatpants who arrived by the busload from all corners of Ayrshire to fuck about with glo-sticks and toot on whistles while dancing like total arses.

You know your childhood is over when you see the kid who sat next to you in double history wearing white gloves, dancing like a cunt standing on a hot tin cunt, topless and covered in cunting Vicks Vapo-Rub.

Ecstasy never made anyone smarter. Didn’t make the music better. “Well,” I hear you say, “at least ecstasy made everyone friendlier! It ended football hooliganism and turned lager louts into nutty geezers!” Yeah, right. The Metro closed in a flurry of stabbings and overdoses. Further down the coast at Hangar 13 (formerly the Ayr Pavilion. I saw The Mission there, supported by The Rose Of Avalanche), three guys died in a space of weeks, boiled alive in their own bodies after necking too many Es and dancing all night to music that literally no-one remembers, music you could only listen to if you were out of your nut on ecstasy.

This is Music, ’90: Students are listening to The Smiths, the Pixies and Billy Bragg. The chart success of Primal Scream’s Loaded means that every indie band from the Wonderstuff to the Soup Dragons are getting a Paul Oakenfold/Andrew Weatherall remix in their quest for a crossover hit. The dance floor is not awash with pills and thrills, it’s awash with snakebite and blackcurrant and dozens of eejits in cardigans who sit down when haw-haw-haw-isn’t-it-hilarious Sit Down by James comes on.

Grunge is well underway – it just isn’t called that yet. 1990 was the year of Alice In Chains’ Facelift, Soundgarden’s Screaming Life/Fopp, Mother Love Bone’s Apple, while Dinosaur Jr were already way ahead of the pack, recovering from their first split with Lou Barlow and the level of fame that came with Freak Scene. Teenage Fanclub picked up on the slacker vibe with Everything Flows but the UK was ruled by the blank-eyed monster that was shoegaze. Shoegaze was like a gateway drug for rave culture: a soulless, trippy wall of noise that made you feel stoned and empty. But in a good way.

There was Jane’s Addiction’s psych-funk classic Ritual De Lo Habitual, Black Crowes’ debut Shake Your Money Maker, the Cramps’ late period charmer Stay Sick!, Depeche Mode’s US-breaking Violator, Gary Moore’s career-changing Still Got The Blues, Nick Cave’s romantic The Good Son, Slayer’s slightly-less-romantic Seasons In The Abyss.

It was the year of possibly the last bona fide AC/DC classic (Thunderstruck), of Passion And Warfare by Steve Vai, Cowboys From Hell, Megadeth’s Rust in Peace, Maiden’s No Prayer For The Dying, The Pogues’ Joe-Strummer-produced Hell’s Ditch, Tesla’s Five Man Acoustical Jam, the Sisters of Mercy’s ‘rock’ album Vision Thing, The Mission’s Grains of Sand and every dope-smoking guitar player’s favourite, The La’s.

It was the year of Beers, Steers and Queers (Revolting Cocks), A Bit of What You Fancy by the Quireboys and the album that helped invent the new wave of Americana, No Depression by Uncle Tupelo. Fugazi’s Repeater, the Pixies’ Bossanova, Sonic Youth’s Goo, World Party’s epic Goodbye Jumbo, The Winding Sheet by Mark Lanegan and the final album from the Replacements, All Shook Down. Hip-hop was still dangerous: it was the year of Fear Of A Black Planet and The Geto Boys. The Cure headlined Glastonbury and Aerosmith headlined Monsters of Rock, joined by Jimmy Page for Train Kept A Rollin’ and Walk This Way.

We spent much of the 80s waiting for ‘The New Punk’, the next musical revolution that would sweep away all that came before it. It didn’t come. The idea that we were all just a bunch of laughable tribes – skins, goths, rockers and ravers – waiting for E to come along and whisk us off to party central? It’s just a load of sniff-banging.

I’m starting to wonder if the swinging 60s even happened.

Listen to our 1990 playlist on Spotify. You can watch This Is England ‘90 here.