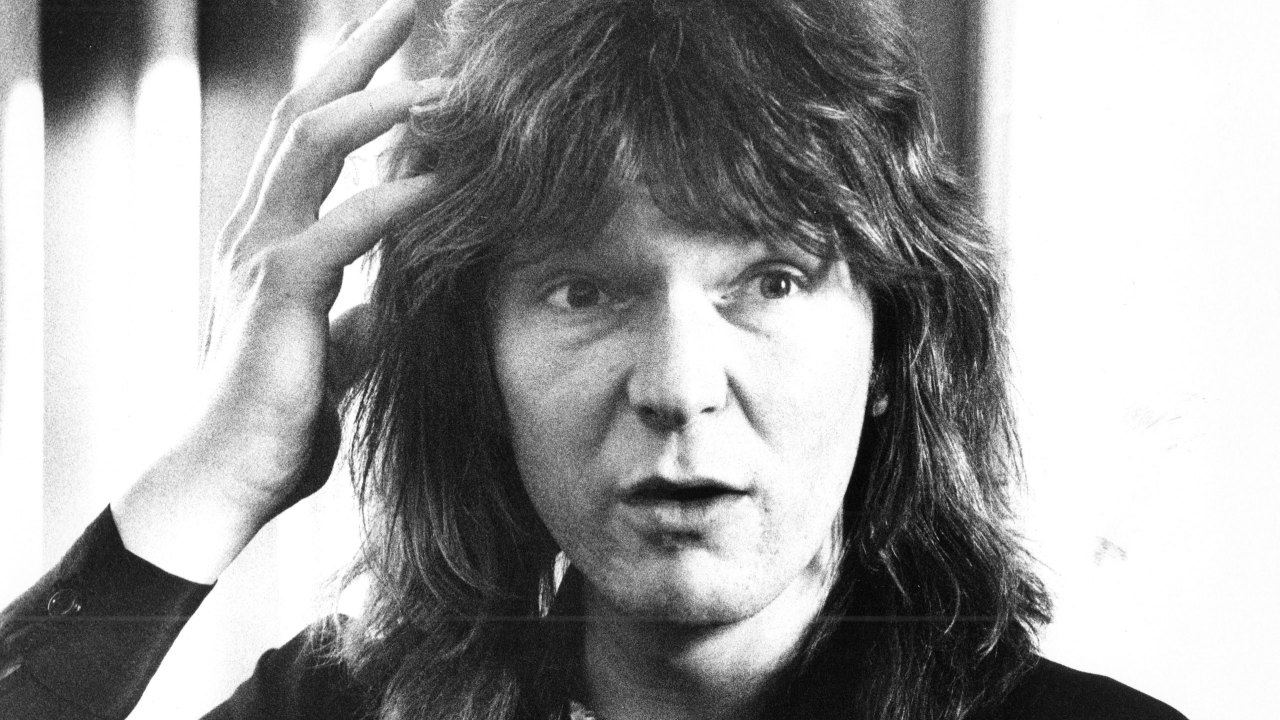

I first met Chris at The Speakeasy in London in 1969 or ‘70.

The place used to stay open until two or three in the morning and I was drinking at the bar when I saw this really tall guy come over. It turned out to be Chris Squire from Yes. There was this lovely barmaid there called Nikki. Nikki went on to marry Chris and he adopted her daughter Carmen. He had two daughters of his own with Nikki, then he went to LA.

How did your friendship develop?

When I lived in Los Angeles in the ‘90s, my house basically became an extension of the Rainbow rooms after two in the morning. You never quite knew who was coming and who was leaving. One night someone mentioned that Chris was around and I said: “Oh my God, I hope he hasn’t brought that singer with him. When that guy’s balls drop, we’re going to have a serious problem!” I couldn’t cope with Yes music, because I didn’t like Jon Anderson’s voice. Suddenly this big hand came around my head and a voice said: “That’s one of the most interesting and truthful statements I’ve ever heard.” And it was Chris Squire. I said, “I’m so sorry, I didn’t mean to criticise,” but he just went: “No, I quite understand what you’re saying.” We ended up becoming very close friends. In fact, he introduced me to my wife. We lived in Beverly Hills and Chris was our neighbour down the road. He used to come over for Sunday lunch and we’d cook roast beef. Chris missed Britain terribly and he’d talk about England a lot. He actually owned the largest thatched house in Southern England at one time, at Virginia Water in Surrey [known as ‘New Pipers’]. It was the most amazing house and in it he built a beautiful studio, where he made all sorts of music [including Yes’s Relayer].

How was his relationship with the other members of Yes?

He had terrible problems with [keyboardist] Tony Kaye. Tony went off with Carmen [Squire’s stepdaughter] and Chris found it difficult going on stage with him. He’d say: “I’m playing in a band with a possible future son-in-law who’s the same age as I am!” Thank God that Tony and Carmen broke up in the end. Chris would often come to me and pick my brains. I’d retired from management at that point and had gone into the Hollywood film business. I had this enormous house with a big studio and a nightclub. This was a time when we were all misbehaving and partying on. Chris was a big man - six-foot five, big feet and big hands – and he would push it. One day I was back to England and got a call from Chris. He said, “On the night you left I didn’t actually go to bed. I went down to Beverly Hills at seven in the morning to go to Mrs. Gooch’s delicatessen and I didn’t feel at all well. So I passed Cedars-Sinai hospital and drove in.” He told me that the car valet had asked if he’d be long term or short term. Chris went: “I’ll tell you in a minute.” And he walked in, then came out on a bed with a drip in his arm, en route to the emergency ward. He sat up in the bed and said to the valet: “I think it’ll be long term!” It turned out he’d had a heart attack. But, with the luck of the devil, he was driving past the hospital when he’d had it. He said to me: “I can’t tell you how much I drank or what I took, but I had a major heart attack. I want you to get on a plane and help me. I need you.” So I got on a plane, flew back to LA and he asked me to become his manager. That was 20 years ago.

Did he rein in his lifestyle after that?

I had to go on the road with him and it was the most extraordinary thing, because when you become a drug taker all the dealers turn up at gigs. So I had to sort all that lot out and, after a while, we had a limit of half a bottle of red wine a day. I literally had the half bottle in my possession and was carefully nurse-maiding Chris. I’ll never forget the time we arrived at Madison Square Garden. I walked backstage and there was a series of plants, the kind you might find in an Ideal Home exhibition, that led along to a door. I asked Chris what was going on and he went: “Don’t ask”. I walked into the dressing room and there was this massive teepee, with Jon Anderson sitting there, cross-legged in a loincloth with crystal champagne. This was my introduction to Yes. At the time, Tony Dimitriades was managing Yes and I was looking after Chris. After that show the band asked me to manage them. I suggested to Tony, whom I’d known since ’68, that we could do it together, but he flatly refused. So off we went.

And how did managing Yes pan out?

Trevor Rabin [guitarist and vocalist] had produced the album Talk [1994], which was in the days of sampling. Chris didn’t like that. He didn’t think it was what Yes was all about; he was very much against a computerised, digital sound at that time. So Trevor and Chris moved away from one another for quite a while and Trevor eventually resigned. In the meantime, Castle had approached me with a view to recording a live Yes album. I thought it was a brilliant idea and said yes, on the condition that we did a new live album with the original members, or at least the classic line-up. So we chose Rick Wakeman, Chris Squire, Jon Anderson, Alan White and Steve Howe. It took months to put it together. We ended up leasing an old building in San Luis Obispo that was once a bank, turned it into a theatre [the Fremont Theatre] and put a notice on the internet that this line-up was going to do a show there. We were invaded by people from all over the world, so we ended up putting on an extra night. We recorded both shows and they became the basis for Keys To Ascension I and II [1996 and ‘97]. Chris then decided to take the band out on the road, but there were so many petty arguments and skeletons that kept coming out of the cupboard. Eventually I resigned and told Chris that I’d help him with his career. I stayed as his confidante and adviser and became his music publisher for 20 years, with Carlin Music.

How do you rate Chris as a musician?

When it comes to bass playing, there was only John Entwistle, Stanley Clarke and Chris Squire. He was the most extraordinary bassist, because he played it like a lead guitar. He had the most unusual tuning system, which I could never get used to, and was quite brilliant. When you saw him rehearsing it was one thing, but on stage he brought a lot of those songs to life. He was like a light. And the other members of the band all complemented each other perfectly. Alan and Chris made an absolutely superb rhythm section. Alan knew where Chris was going before he even went there. It was quite something to see them in action. It was just a shame that there were so many problems between the band on the road.

When was your last contact with Chris?

Chris ended his life in Phoenix, Arizona. The last contact I had with him was when he sent me a text in early June saying: “Don’t panic. I’m in a new, secure room in a section of the hospital and I don’t want you to come out and see me. They’re only doing tests and I’ll call you in two weeks.” But he died so quickly. I’ll always remember him as a wonderfully kind man, someone who never stopped smiling. And those big hands worked that fretboard like no one else.