The following extract is taken from Genesis: 1975 to 2021 - The Phil Collins Years, by Mario Giammetti, available now via Kingmaker Publishing from Burning Shed.

By June of 1977, Genesis were back on the road in Europe after playing an extensive (and successful) North American and Brazilian tour. They started out in Stockholm on the 4th before moving on to Berlin. The band then played four shows in Paris (recordings from these concerts in the French capital were released a few months later as the extraordinary live album Seconds Out), followed by dates in Cologne, Offenbach am Main and Bremen in Germany, before three shows at London’s Earls Court opened by Richie Havens.

The Wind And Wuthering tour succeeded in consolidating Genesis’s standing; at long last they were stars in the UK, popular throughout Europe and had a growing following in America, added to which they gained their first and fantastic foothold in the South American market.

The five musicians were, quite simply, in magnificent form. New boy Chester Thompson was the perfect drummer for Genesis, with his great technique placed at the band’s service. Now, more confident than ever in his role as frontman and having acquired a certain amount of rapport with the audience, Phil Collins sang perfectly, ironing out the few imperfections of the previous tour, and his contribution on drums was spectacular, not only in the instrumentals …In That Quiet Earth and Los Endos, but also in sections of One For The Vine, Robbery, Assault And Battery, Firth Of Fifth, Supper’s Ready and, doubling up on drums, the final sections of Afterglow and The Musical Box.

Mike Rutherford was at the top of his game as an instrumentalist too, playing on his new Shergold double-neck guitar with a 12-string at the top and bass at the bottom, not forgetting his essential contributions on bass pedals. Tony Banks was phenomenal as always on his array of keyboards, while Steve Hackett (who on the previous tour had stopped playing sitting down) appeared at perfect ease, with his guitar solos enjoying greater space than usual.

With major success finally knocking on their door, what more could Genesis want? However, for one band member, all their success did not appear to be enough.

Steve Hackett: “I was starting to write more and more material and it was harder and harder to incorporate that into a band format. Plus, I wanted to work with other people. Brilliant though the members of Genesis were, I felt I had to take the risk in order to find out just how good I was on my own. There’s a voice that tells you that you’ve got to see whether you’re up to scratch or not. Doing the first solo record [Voyage Of The Acolyte, 1975] was a bit like turning on a tap.”

Tony Banks: “I think Steve probably felt that he couldn’t get enough of his own writing into the band. He felt that Genesis was always going to be dominated a little bit by what Mike and I decided and that he wouldn’t be able to get his stuff through. I have to say, there were various things that he wrote that we didn’t do, you know, that maybe we didn’t particularly go for.

"The important thing was that we all had to like it, unless you shouted very loud, in which case you ended up doing it anyhow, like I did with One For The Vine. I think he felt frustrated by that and I’m sure that was one of the reasons why he left. Beyond that, I’ve no idea. Perhaps he thought it was time to try and go solo and, you know, take his chances.”

Hackett: “Wind & Wuthering [1976] is a great album, and the stuff I had left stood me in good stead for future albums. Some of the ideas I had presented to the band and were turned down went on to [his solo albums] Please Don’t Touch! and Spectral Mornings.

"Forty years ago I had something to prove, and I still do. I don’t think group’s members should be competitive with each other, you should try to bring out the best in everyone. If I work on a solo album for someone else, whoever they are, I do what they want. If Tchaikovsky asks me to do a guitar solo, well, he’s the boss… But in a group it shouldn’t be like that.

"But one person always wants to be the Fuhrer. The Beatles, the Stones all managed to produce good stuff, but I sympathise with Bill Wyman, who wrote the riff Jumpin’ Jack Flash is based on but got no writing credit at all for. I can’t complain with Genesis because I am credited with a number of things that I didn’t really write, as we used to put it all as being done by everyone.”

Banks: “I always suspected that Steve was going to leave at some point, but I thought with Wind & Wuthering things would be okay, as he was getting rather more across on that album. But I think, having done a solo album, he had psychologically moved on. But we certainly missed his presence on the next album.”

Genesis had never been so popular. As soon as the Wind & Wuthering tour was over, they began work on mixing a live album, mainly from recordings of the Paris show held on June 14, 1977 (just one track, The Cinema Show, with Bill Bruford on drums, was taken from the previous tour). It was right in the middle of all this that Hackett left the band.

Hackett: “When we were doing the A Trick Of The Tail tour, one of the guys from Chrysalis Records asked if he could film one of the soundchecks and the band agreed. But because it was Chrysalis [the label that had just released Hackett’s solo album in America] the camera was on me.

"Mike Rutherford got very annoyed, threw down his guitar and walked off. Then he wanted to have a meeting with Tony and myself. He had obviously spoken to Tony and wound him up, and this is where it all came out. They started saying: ‘We don’t think you’re giving everything to the band’, blah blah.

"So I said: ‘Well, give me space within the band.’ But that wasn’t on offer. Clearly Tony felt that they could be a huge success without me… and who was I to doubt them? So I stuck with it for one more album [Wind & Wuthering] in case there might be a change in the amount of ideas that I might give. But, as you can see, it’s got Tony’s credits everywhere.”

Mike Rutherford: “I’m not quite sure to this day what happened, really. We were mixing the live album, and Phil bumped into Steve in the street. He’d said hello but then he didn’t come into the studio. It was sort of weird really, I’m not sure we knew what was going on. He didn’t come and talk to us, he just sort of left. But in a way, maybe I sensed it coming. His solo album had been very important to him and I think he wanted to do more work in that area. And probably he felt that with Genesis he couldn’t be as free.”

Collins: “We were mixing Seconds Out and I passed him on Ladbroke Grove waiting for a cab. So I stopped and said: ‘Hey, hop in, I’ll take you there.’ He said: ‘No, no. It’s okay. I’ll call you later.’ I didn’t think anything of it. When I got to the studio, I said I’d seen Steve, and Tony and Mike said: ‘Did he tell you?’ ‘Tell me what?’ And they said he’d left.

"He has since said, apparently, that had he got in the car with me that day, he wouldn’t have left the band. He said I was the one person who would’ve talked him out of it. It’s probably true. I’d have worked out some way of being the diplomat. I can be that sometimes, when there’s a difficult situation between people. I’m a confrontationist, to be honest; I’d rather say: ‘Listen, if you’ve got a problem with him, sort it out now.’”

Hackett: “I was providing a lot of material for the band at this point, but in terms of writing credits I wasn’t really getting what I thought I should. I had already managed to get a hit album on my own, so I needed to be respected as a writer, and I don’t think I was getting that from Mike and Tony. I think their agenda was always to run the band. Pete [Gabriel, former frontman], who had been an enormously important part of the band, had always wanted a democracy, as had [early Genesis guitarist] Anthony Phillips.

"Democracy in bands is a great ideal, but rarely works in practice because to achieve it you need to recognise everyone as being equally talented as yourself, and I think that’s difficult for certain people to take on board. It’s usually one talented person who ends up getting their way more than the others. But it doesn’t keep bands together forever, as everyone needs to develop. I think to get a band like Genesis to all flow in formation, to make an album like Wind & Wuthering, was quite an achievement.

“I gave it everything I had and I gave it as much as I was allowed. By the time I was doing A Trick Of The Tail [’76] I felt I was a fully-fledged writer, rather than someone who was learning from the others who had been writing more fully in the early days. Although I was already writing some stuff with Phil way back on Nursery Cryme: For Absent Friends and parts of The Return Of The Giant Hogweed, The Musical Box, Fountain Of Salmacis.

"If I’d been more of a politician I may have ridden it out, but I wasn’t given the chance to continue doing solo albums whilst I was a member of the band, even though Phil was allowed to work with Brand X [the first album by Brand X, Unorthodox Behaviour, came out in 1976]. Maybe if I’d had another band I’d have been allowed to do that, but not under my own name.

"Tony said I couldn’t do more solo albums and be a member of Genesis. Tony was assuming leadership at that point and Mike was backing him up, so there was no guarantee of a proportion of the songwriting being divided up equally. Tony said: ‘If you don’t like it, you know what you can do.’”

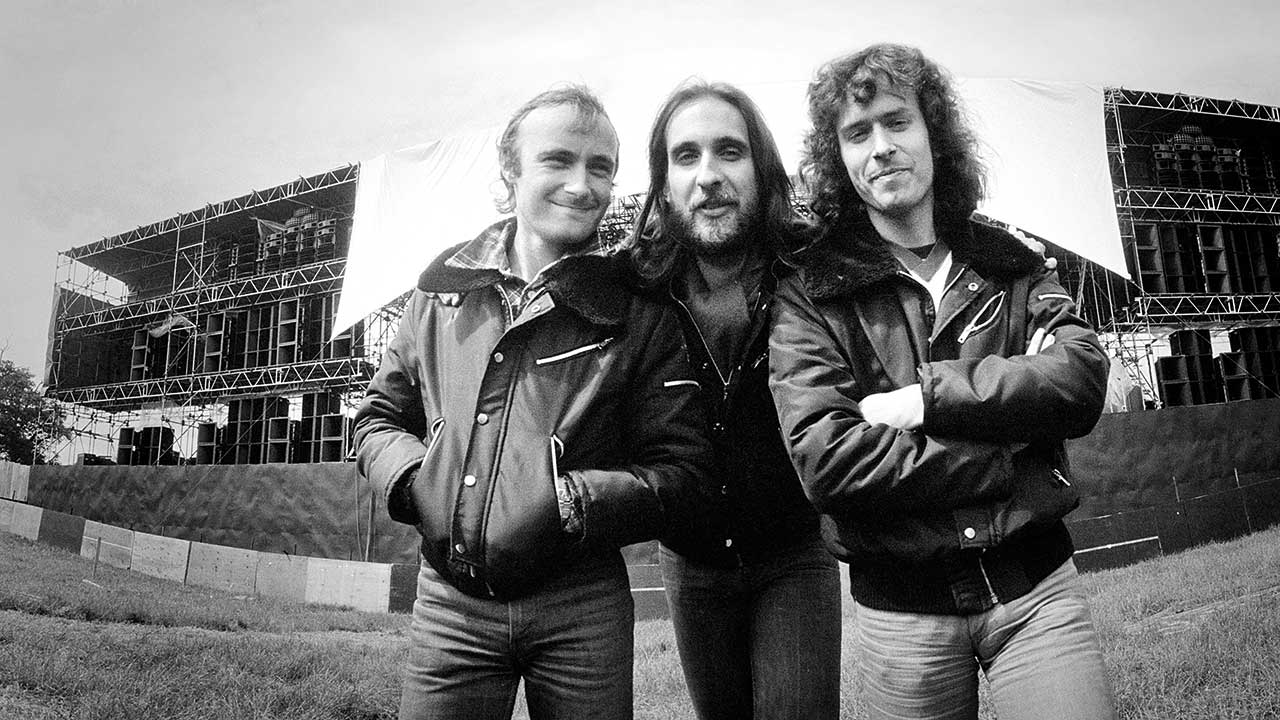

Hackett’s departure left the remaining members of Genesis faced with a major decision: bring in a new musician, or carry on as a three-piece.

Banks: “I don’t think we really thought twice about it; we knew we could do this. Not only because we’d already been through it with Pete, but while the lead guitar and everything that came with that was Steve, the rhythm guitar, which had been so prevalent in things like The Cinema Show or The Musical Box, had always been Mike. The only thing was whether or not he would also be able to cope with lead. He definitely had to work a bit to get the right mind-set for that."

Rutherford: “I don’t think any of us really thought about getting in another guitar player. Having replaced Peter with Phil, we knew we’d get a good feeling from the audience with someone who was already in the band. Guitar-wise, I’d done an awful lot of stuff but I hadn’t really played lead, that was Steve’s job and he was a great lead player. But I think we felt we could sort this out in-house.”

Collins: “Mike had a big mountain to climb, because being a guitar player is one thing, being a fluent lead guitar player is something totally different. He struggled with that for a little while.”

Rutherford: “Yeah, but I was quite excited too, you know. When a change happens, you’re forced to do something else, which is often not a bad thing.”

And so it was that in August 1977 the trio were already in the rehearsal room writing new material. In terms of writing, Steve’s absence didn’t create any real issues; if anything, it made things easier. The guitarist was growing significantly as a composer by that point, and Tony and Mike, traditionally the main songwriting forces in the band, were reluctant to give him more space.

His leaving therefore resolved disagreements that had built up over the last couple of albums: without Peter and Steve, and with Phil largely continuing with the role of arranger rather than composer, Tony and Mike finally had the chance to control almost the entire songwriting process. Which, in reality, is essentially what they had been doing ever since the departure of Anthony Phillips.

Banks: “One great advantage of there being fewer people in the band was that we had even more writing space. We were doing one album a year at that point, as we hadn’t done any solo albums, so we did tend to fight a little bit to get our stuff on the album.”

After about six weeks of rehearsing at Shepperton Studios, the trio had managed to sketch out about 15 songs, 13 of which would be recorded in September and October, again in Relight Studios in Holland with co-producer David Hentschel. A new direction was immediately evident, with the band focusing more on the song format and showing a marked loss of interest in extended instrumental passages.

Banks: “When we were writing for four and I wanted to write a solo, it meant that Steve, for example, would just busk along and then have his moment elsewhere. Mike and I had written various instrumentals over the years, it just didn’t happen this time round.”

One of the consequences is the distinct lack of solos on …And Then There Were Three….

Banks: “There are keyboard solos, like on Down And Out or Follow You Follow Me, but they are short, concise things which just really fit with the chords. They’re not separate solos in the way they were with previous albums. There’s not much lead guitar on this album, just two or three parts, but what there is, Mike plays them well. So that was a loss I think. And from my own point of view, in losing Steve I had lost an ally. You know, we both liked to do weird things and we could sometimes drag it along that way for a bit longer."

In September 1977, continuing at the band’s usual unstoppable pace of that period, Genesis had a new album ready, but it was decided to delay its release for a few months while they planned a new tour. Yet again, fans were oblivious to the change in line-up.

Hackett: “When Pete left, he agreed not to release the news officially for some months, and I honoured the same agreement, so news of my departure was released when it was most beneficial to them rather than to me. I deferred so that I could help the group as much as possible. I’m not a competitive guy and neither is Pete.”

The announcement came in October 1977, coinciding with the release of Seconds Out, a stunning double live album that did very well in the charts (No.4 in the UK, No.47 in the States). Shortly afterwards came the announcement that a new studio album was to be released, with a title, …And Then There Were Three… It turned out to be a totally different album to anything Genesis had previously recorded.

Banks: “The idea of trying to keep the songs a little more concise and to get more ideas on the album was quite appealing. The other thing about this album is that it was written when Phil was probably most distant from the group in many ways, so Mike and I ended up writing just about all the tracks individually, apart from Follow You Follow Me, which emerged more in the studio as a group track along with a couple of others like Ballad Of Big and Down And Out.

"But the rest of it was almost like a dual solo album. I did Undertow pretty much as I would have done as a solo project, and the same thing goes for Mike with songs like Snowbound or Say It’s Alright Joe. Which produced a certain kind of result.”

Collins: “This is probably my least favourite record, but maybe that’s just because it wasn’t a particularly happy period in my life. I contributed little bits, but the songs were kind of short, a little inconsequential, I felt, apart from Follow You Follow Me which I thought was great. I remember writing some lyrics for different things, but certainly not the kind of lyrics I would go on to write a couple of years later [on Genesis’s next album, Duke], which were much more personal.

"I suppose there are a couple of lyrics in there that I might have written based on personal experiences, but I was still writing some fantasy things, based on what the Genesis history was, as opposed to what I would become. I was always more direct, while Genesis were always more ‘round the houses’ storytellers.”

Rutherford: “We were starting once again to find slightly simpler styles of playing and writing, and lyrically speaking, Tony was simpler, more immediate. In a way there was less desire to always prove that we could do complicated stuff and do long songs to make it work. We were getting better at writing short songs.

"We were always very intense young men, trying to prove that we were the best and the greatest at everything, and suddenly we were getting a bit older, we had kids… Maybe you just reach a moment in life when you feel you don’t have to try so hard. Songs like Follow You Follow Me and Many Too Many, for example, I don’t feel like anyone was in any way trying, and I think that’s why they work well.”

The album finally came out in March 1978 and starting with the title, …And Then There Were Three…, it immediately revealed a different side to a band that was in continual evolution. Having made the decision to concentrate more on shorter songs, the album comprises 11 tracks, on average lasting around four minutes, making it without doubt the most accessible album the band had made since their naive debut back in 1969.

Gone are the long instrumentals, replaced by short and structurally more linear compositions. Mostly absent too are the sudden changes in rhythm and syncopated time signatures. And the acoustic 12-string guitar sections, while present in Snowbound, Undertow and Say It’s Alright Joe, were much less of a feature. The aim, in other words, was to create an album of seemingly simple songs.

However, while the songs were more straightforward, a feeling of sadness surfaces more than once in both the musical atmospheres and the lyrics. Obviously the result of an understandable state of internal upheaval, the album also highlights a division in roles that had never before been so marked: Collins is the singer/ drummer, Rutherford the bassist/guitarist, Banks the keyboard player; no backing vocals for Rutherford and Banks, and no guitar for Banks.

The spotlight is obviously on Rutherford. He does his best on lead guitar, giving just a few, simple solos which are often overdubbed with harmonies on a second guitar, for example on Many Too Many, but he is still in magnificent form with his rhythmic riffs and on acoustic guitar, while his bass playing remains remarkable (and definitely worthy of acclaim on The Lady Lies).

Without Hackett, Banks could finally take centre stage as the unchallenged soloist of the band. That said, there are very few solos on this album and, apart from the one on Down And Out, they are all of very simple execution. Collins plays and sings well, but it is easy to discern his detachment from the band and his lack of involvement at a time when he was going through both personal and artistic issues.

The end result is therefore a somewhat individualistic record, with only three of the songs having been written by the group as a whole. That said, it would be desperately unfair to hastily dismiss an album that still holds some moments of dazzling beauty: the irregular opening of Down And Out, the poetry of Undertow, the complexity of Burning Rope, the disturbing tenderness of Snowbound.

As albums go, it is a product of its time which, if nothing else, has the indisputable merit of disproving all those who had off-handedly tarred Genesis with the same brush as their peers, bands such as Yes and Emerson, Lake & Palmer who, with their Going For The One and Works Volume 1 respectively, showed that they really hadn’t grasped the fact that, musically, times were changing. Other bands, however, were faring better, such as Jethro Tull with their pastoral Songs From The Wood, and Pink Floyd with their claustrophobic Animals.

In the meantime, a more immediate pop-rock genre was growing in popularity, led by bands such as Fleetwood Mac (who had hit the jackpot with Rumours) and the Electric Light Orchestra (Out Of The Blue achieved significant success).

More importantly, The Damned, Television, The Clash, The Stranglers, The Jam and Talking Heads each released their debut album, while Peter Gabriel brought out his first solo album (self-titled, aka Car), Bob Marley released Exodus, and David Bowie was exploring new territory with “Heroes”.

Genesis, however, still had many strings to their bow and couldn’t wait to prove it. Consequently, …And Then There Were Three… constitutes a transition that was absolutely essential if the band were to continue into the 1980s, which were just around the corner.

Their first album without Gabriel, A Trick Of The Tail, sold more than any of their previous releases, and the same happened with the first album after Hackett’s departure. In fact …And Then There Were Three… consolidated the band’s success on home territory, where not only did it reach No.3 (as high as A Trick Of The Tail and four places higher than Wind & Wuthering), it also managed to stay in the Top 100 for a year. In the US, it got as high as No.14 and earned the band a gold record.

These impressive chart placings were surely assisted by the first hit single in the history of Genesis: Follow You Follow Me, which made it to No.7 in the UK and No.23 in America.

Collins: “Follow You Follow Me was a huge hit, not only in Europe but also in America, and that made a big difference to us. It was another step on that ladder that made us a bigger band. We were playing to more people, there was more interest, more play on the radio, and suddenly there were even a few girls in the audience.”

After the last show of the …And Then There Were Three… tour in the US (Houston, on October 22, 1978) the band returned to the UK for a few days. On arriving home, Collins was greeted with a bitter surprise. Tired of a husband who was always on the road, his wife, Andrea, had run off with the painter and decorator who was doing up their apartment, and taken the two children with her.

It came as a huge shock, but Collins had no time to dwell on it as Genesis were scheduled to make their first trip to Japan, to exploit the success of …And Then There Were Three…, their first album ever to enter the Japanese chart.

While the record label and management had reason to be pleased with the album’s success, the same could not be said of the band’s long-standing fans. The more immediate nature of much of the music created what can only be described as a watershed moment between old and new fans.

Many of those who had already had difficulty digesting Gabriel’s departure now lost all interest in Genesis. But in absolute terms the band had never had it so good. Collins, however, was quite understandably at rock bottom…

This exclusive extract is taken from Genesis: 1975 to 2021 – The Phil Collins Years by Mario Giammetti, published by Kingmaker, and available from Burning Shed. Reproduced with kind permission.