Rock fans of the late 70s might have claimed her as their own, but in fact Black Betty was older than she seemed. In December 1933, the noted American ethnomusicologists John and Alan Lomax set up at Central State Farm in Texas – actually a prison where convicts produced sugar cane and cotton – to record an a-capella take by career criminal James ‘Iron Head’ Baker, which is believed to be the song’s first rendering.

The 63-year-old couldn’t claim authorship of Black Betty, which had likely been hollered under the burning sun as an African-American work song since the first slaves landed. But whether the ‘Betty’ of the title meant a bottle of whisky, a devious woman, a police car or the bullwhip that bit at the workers’ backs, Baker – self-described as “the roughest n**ger what ever walked the streets of Dallas” – knew of what he sang, and his vocal was an eerie moan that even Lead Belly’s first commercial recording for Musicraft Records in 1939 struggled to match.

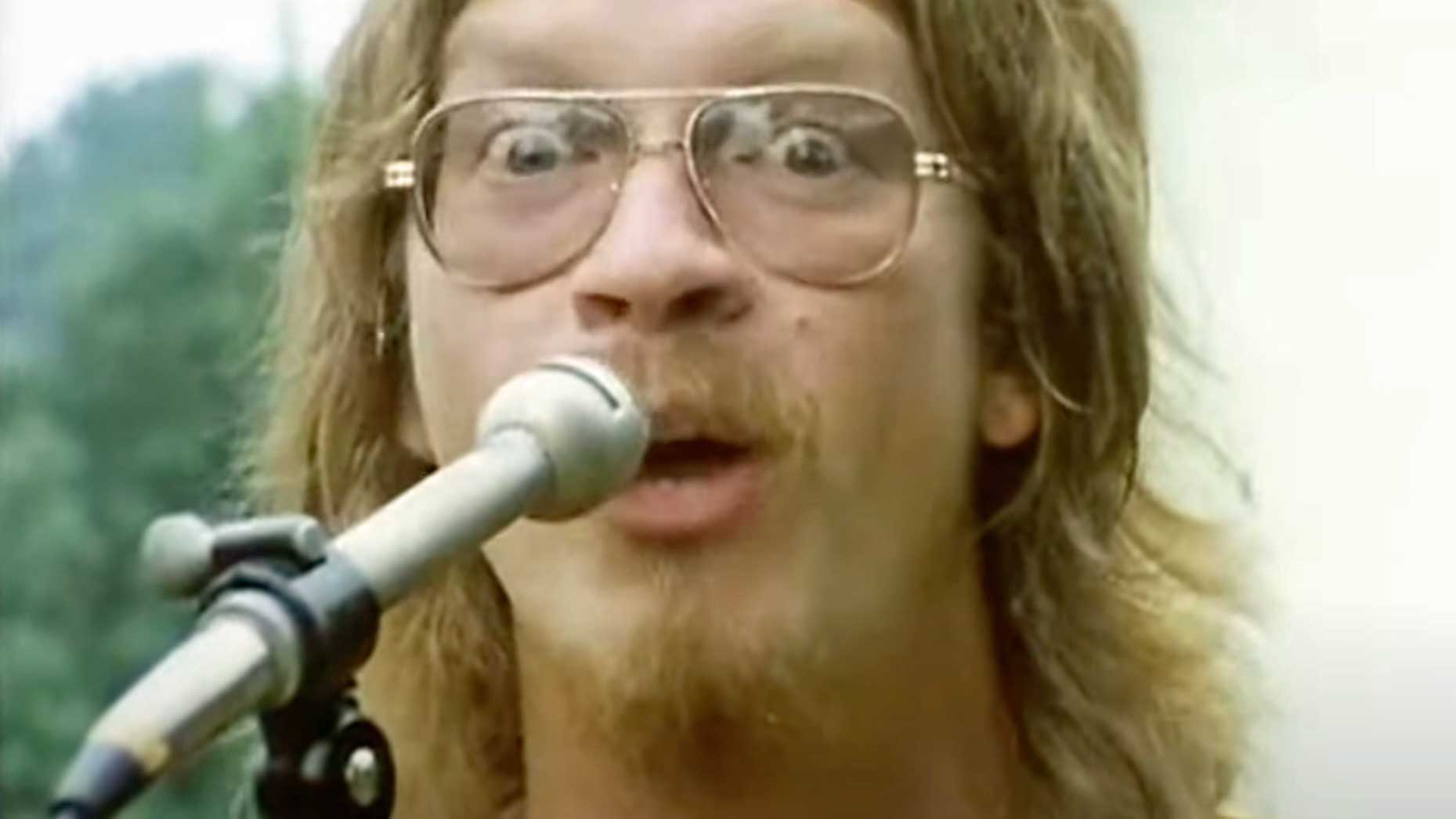

Yet it was the Lead Belly version that caught the ear of one Bill Bartlett. A sometime member of 60s psych footnote the Lemon Pipers (famous for 1968’s Green Tambourine), the guitarist set to rearranging the song in the mid-70s, adding a choppy southern-smoked riff and two extra verses, then issuing a low-key release by his then-band Starstruck.

Everybody asks: ‘What’s Black Betty about?’ Bartlett explained in a recent interview. “My version is about Bettie Page. She’s not a black girl, she’s a pin-up queen from the fifties. She was the tops. She was my inspiration for writing the last two verses. I don’t know what Lead Belly was writing about. That’s up to anybody to guess. But music can be whatever you want it to be about. As long as you’re having a good experience listening to the music, I don’t care what you think it’s about.”

The track’s regional splash was enough to lure Super K Productions executives Jerry Kasenetz and Jeffry Katz, who put Ram Jam together around Bartlett and re-released it as a single in 1977. But, as the singer was at pains to point out, the band in the video was not the band playing: “Ram Jam did not cut Black Betty. It was Starstruck.”

Sung by white men who had their liberty, the Ram Jam version doesn’t have the depth or pathos – how could it? But just as Cream’s Crossroads means less but thrills more than the Robert Johnson original, the same principle applied to Black Betty. The opening cludding drum beat sets up that scuffed guitar riff, then all the instrumentation drops out except the hi-hat and Barlett’s vocal.

A chippy, charging thing that can barely keep up with itself, it was irresistible. Black Betty was intended as a visceral, not an intellectual, experience – a song that demanded movement – and in 1977 it delivered on that brief. After hearing the whipcrack Ram Jam interpretation, to return to the original was to wade through treacle.