Gary Moore was off the road and hardly in the studio during 1993, until he took a call from former Cream bassist/vocalist Jack Bruce, who had just lost his guitarist Blues Saraceno to the glam-metal band Poison. Jack had a couple of gigs coming up in August in Esslingen, Germany, where his wife Margrit was born. Steve Topping was down to play the first night, but couldn’t do the second, so Jack asked Gary if he fancied stepping in.

Gary Husband was Jack’s drummer at the time: “I was immediately pretty impressed by Gary’s ‘lightning strike’ impact as a guitarist. He meant every note, and that means a lot to me. For the majority of the time we were playing Cream material, which wasn’t my favourite endeavour with Jack because I always hated trying to fill someone else’s shoes in a very particular and personally formed way of playing. Gary, on the other hand, came in and ‘owned’ those songs, seemingly from moment one, almost as if he had been the guitarist in the original group. It was always very impressive how he did that.”

Gary Moore told me in 2009: “That gig in Esslingen went so well, I asked Jack if he fancied doing some writing together, because I was planning the next Gary Moore album.”

Gary had tried to set up a studio in his house in Shiplake in Oxfordshire. He experimented with the changing room of the outdoor pool but it didn’t work, so he rented a house nearby that would serve as an office and an eight-track studio. Gary said: “Jack would come over and would work with me during the day. I’d written some songs, but it was kinda weird because the songs were moving more his way and I was starting to think of Jack singing them.”

At the beginning of November 1993, Jack celebrated his 50th birthday with an all-star concert over two nights at the E-Werk in Cologne, featuring many of the musicians he had played with over the years, including Ginger Baker, Simon Phillips, Clem Clempson, Dick Heckstall-Smith, Pete Brown and Gary Husband, and Gary Moore was invited to take part.

On the day the musicians gathered to be taken by coach to the venue, Gary disappeared into a limo – to much mutterings about “bloody big-headed rock stars”. The limo was following the coach, but when the coach pulled up outside the E-Werk the car vanished, and Gary with it. He arrived about an hour later. It turned out he was nervous about this very important gig and had instructed the driver to park up away from the venue while he sat in the back with his guitar and practised.

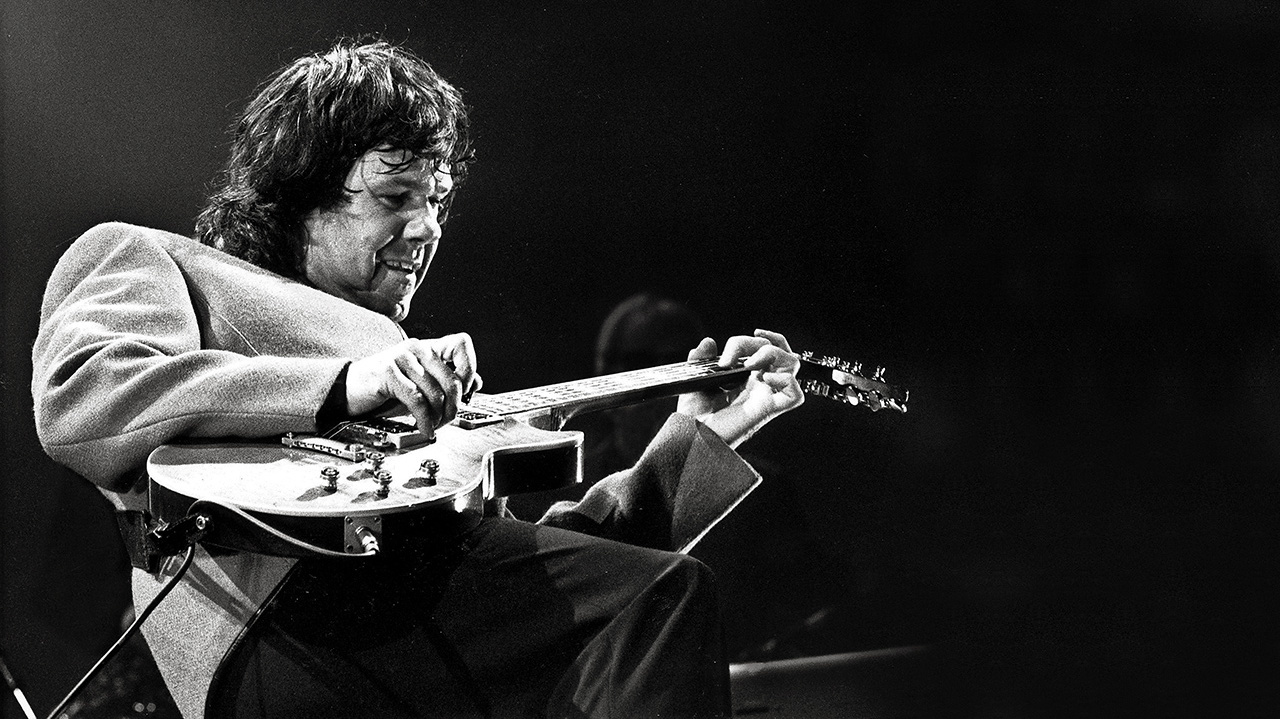

With Clempson playing lead guitar on the first night, Gary stepped up for the second. He began with Jack and Simon Phillips, playing Jack’s frantic Life On Earth, a revved-up version of the riff of Cream’s Tales Of Brave Ulysses played at breakneck speed. For the past three years, Gary had been retraining himself in the art of blues restraint. Now he was off the leash – Gary Moore, rock guitarist, red in tooth and claw, harking back to the frenetic fusion workouts of when he was in jazz-rock band Colosseum II. Jack was loving it – they faced each other, exchanging riffs and smiles, driving each other on. Simon finished off with a drum solo, while Jack and Gary stood to the side, arms around each other.

Simon began the beats to NSU and then left the stage as Ginger picked up the refrain. Gary must have thought all his Christmases had come at once. When he played Cream’s NSU nearly 30 years ago, in front of hordes of amazed Belfast teenagers, could he possibly have imagined that one day he would be playing the Eric Clapton role in front of a packed German audience – where Gary had a large and enthusiastic fan base – alongside two-thirds of Cream?

They carried on with Sitting On Top Of The World, Politician, Spoonful and White Room. It was a bravura performance by Gary – truly owning the songs, as Gary Husband observed. The years between Ginger and Jack fell away – they were as powerful as ever, and even Ginger could be spotted smiling at the back.

And from that came the most unexpected twist in the tale of Gary Moore.

Early songs that Gary and Jack worked on included City Of Gold, Waiting In The Wings and Can’t Fool The Blues. The project was geared towards Gary’s next album, which, on the strength of the songs he was writing, wasn’t planned to be another outright blues album. Gary Husband had been told that the project was in the offing and that both Jack and Gary wanted him involved. Yet the weeks went by and the drummer heard nothing, so by the time the call came to go into the studio, this multi-instrumentalist musician was committed to doing an album as Billy Cobham’s keyboard player.

“Amazingly,” said Gary Moore, “Jack suggested we get Ginger over. I said: ‘Are you sure about this?’”

Jack and Ginger had managed to get through a one-off gig with no traumas, but the pair’s love/hate relationship was legendary. Could it possibly work as a band? Jack had no such qualms. “Yeah, yeah, it’ll be great,” he said. “Don’t worry.”

Now with Ginger involved, they were looking at a very different beast. Realistically, it could no longer just be Gary’s next album, with Jack and Ginger as ‘backing musicians’. This was a whole new project, and they needed to secure an album deal as a band in their own right.

Steve Barnett had moved to the United States to establish Hard To Handle management, as the US end of Part Rock. This worked fine for Gary when he was living in Connecticut, but it was much more difficult when he returned to the UK, and so Gary’s day-to-day management passed to Steve’s UK partner Stewart Young. Meanwhile, Gary had a new tour manager, John Martin, who during the course of 1993 found himself thrust rather reluctantly into the role of manager, as the arrangement with Young wasn’t working out. Nonetheless, Steve was the deal-making wizard and he flew in to negotiate with Virgin Records.

Steve was presenting to Virgin that much maligned concept ‘the supergroup’, which had a topical edge. Back in January 1993, Cream had been inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame. They played together in public for the first time since Cream broke up in 1968, hugs and glad-handing all round, creating a major buzz through the business that they were going to re-form. However, that was always Clapton’s call, because he had the organisation behind him to make it happen, and, probably with one eye on his own solo career, he didn’t want to do it.

Now, with the industry still talking about Cream, Virgin were presented with the chance for two-thirds of Cream to combine with their star guitarist in what the German show had already demonstrated was a potentially monstrous band. The deal was struck for a ‘non-commitment’ album – that is, not part of Gary’s main deal with the company.

At that point, John Martin had yet to officially take over from Young: “I remember driving back with Steve to Heathrow,” he recalls, “and telling him that Gary had asked me to manage him. Steve’s expression suggested it wasn’t going to be a day at the beach. He said to me: ‘Are you really sure you want to do this?’”

No doubt, John’s initial foray into management would be something of a baptism of fire.

It all started calmly enough. The new band went into the large residential studio at Hook End, Berkshire. And as a present for Ginger, Gary’s team managed to track down Ginger’s old Ludwig double-bass-drum Cream drum kit on sale in a drum shop in North London. “Ginger walked in,” said Gary, “and he was just freaked when he saw it. But he didn’t end up using it because it didn’t sound as good as his modern kit.”

Gary did have concerns, though, when Ginger first arrived at the studio, as producer Ian Taylor explains: “Ginger had been paid a lot of money for the session, flown in from America Business Class and so on, and he turned up with hands full of cuts and calluses. Turned out that Ginger had been building fences for his horses and his hands looked like a stockman’s.”

He also had a whopping great bump on his head. Apparently he had been doing a spot of roof repairs on a windy day. He tried to grab his hat as it blew off, forgetting that he was holding a hammer at the time.

After they ran through some Cream songs to warm up, “we started putting down tracks and it was very easy,” Gary said. “There was no problem at all. It was really fun and I got a great insight into the chemistry between Jack and Ginger. It wasn’t what I thought at all; they weren’t at each other’s throats. I think Jack really looks up to Ginger, and Ginger knows it, so he’ll never tell him he’s any good. They’re like two brothers, just winding each other up.

“One day I said to Jack: ‘Can you ask Ginger to play the hi-hat pattern like he did on Born Under A Bad Sign?’ ‘No way. I’m not fuckin’ asking him. You ask him.’ So I just pressed the button in the control room and asked him to play that pattern and he said: ‘Yeh, sure, man. No problem.’ And Jack looked at me speechless. They were just like an old married couple. It’s just the way they were.”

Ian Taylor agrees that, for the most part, and given the egos, it was remarkably plain sailing.

“We did have one problem over timing with Ginger. For some reason we were using a click track on Where In The World, and Ginger just couldn’t or wouldn’t get on with it. It can be a problem for the older drummers. I remember doing a session with Gary and trying to get Cozy Powell to play to a click track – it was terrible. But Gary was a bit fanatical about timing, and eventually we used Arran Ahmun on drums. But apart from that it was fine.”

As it was a band project now, they needed a name. Some of the ones they came up with were Driver’s Arm, Rocking Horse, Herbal Remedy, Worldwide Cargo, Mega Bite, In + Out, Piece Of Cake, Thrilled To Bits, Tit Bits, Fantastic Three, Grand Three and Expanding Universe, the latter of which was the front runner for a while. Nothing stuck, though, and eventually they settled for BBM – although not before a band called Bang Bang Machine tried to kick up a fuss.

Once the album was in the can, they started thinking about the cover. They used David Shineman as the photographer. John Martin says: “We did a session all day of them individually, Jack playing cello and so on. At one point, David asked Ginger to stand in front of some angel’s wings that had been used for a fashion shoot. When we got the contacts sheets back from Virgin, it was such a strong image.”

It was also the most amazing juxtaposition: rock’s Grade-A curmudgeon in a long black coat, smoking a fag, presented as a heavenly celestial being – one of rock’s classic album covers.

The album, Around The Next Dream, was released on May 17, 1994 at the start of the tour. The whole vibe about a possible Cream reunion, and the fact that half the songs clearly had their Cream antecedence, gave the critics ample ammunition for comments along the lines of: ‘They couldn’t get Eric, so they got Gary instead’, which was a world away from the truth.

Gary recalled that one interviewer actually asked him: “Have you always wanted to be Eric Clapton? And now you can be?”

“And I thought: ‘No, fuck off.’ And then Ginger chimed in with ‘Gary plays like Gary. Eric plays like Eric.’”

Jack also found the ‘ersatz Cream’ jibes very irksome: “We deliberately wanted to nod towards Cream. It was around the time when Oasis were copying The Beatles, so I thought: ‘Why shouldn’t I do a copy of me?’ So it was very deliberate, and I thought it worked very well.”

Some reviewers did buck the trend: Q magazine concluded that the album was “satisfyingly well rounded… which proves that BBM are not Cream re-formed with one notable omission, but a credible band in their own right.”

Even the ever-astringent Charles Shaar Murray, writing in Rolling Stone, felt that improved recording techniques gave this band a sound that was “bigger, cleaner, rounder and more defined than the often fuzzy, scuzzy, over-compressed Cream”, and thought Gary had out-Gibsoned and out-Marshalled his illustrious predecessor.

Despite all the carping, the album sold well in Europe and got to No.9 in the UK chart.

The reviews of the album came out once the tour was under way, and it was BBM on the road where the whole project began to fracture.

They played a ‘worst-kept secret’ warm-up gig at the Marquee in London, and the band almost folded there and then. With Cream, the sparring was between Jack and Ginger, with placid Eric staying out of it or trying to act as peacemaker. Whatever label you want to pin on Gary Moore, ‘placid’ would not be one of them: a Celtic band leader in his own right came up against Jack, another fiery Celtic band leader hewn from the same rock.

The studio and the stage are two totally different environments. On stage you’re in front of a paying audience, there is a ‘performance’ going on, no retakes or overdubs, somebody has to cue songs in and out. It was all about who was the leader on stage.

BBM rehearsed at Peter Gabriel’s Real World Studio in Wiltshire, drove into London for the sound-check at the Marquee, and all seemed fine. But when it came to the gig, according to Gary: “I was only using a small amp because it’s only a small place, so I thought I’d better not play too loud, so I used a fifty-watt Marshall. But Jack had about three bass rigs, and I think he turned them all on at the same time and nearly blew me off the stage. So I’m screaming at the roadie: ‘What the fuck is going on? All I can hear is the fuckin’ bass.’

“And then I said something to Jack afterwards and he gave me this filthy look: ‘I don’t like to discuss gigs after the gig. I have a rule.’ I then said something really bad back and he was really upset. Ginger was outside having a fag and says: ‘See, Gary, that’s what broke Cream up.’”

Jack did say later that “Ginger really did unsettle me that night. He was in such a bad mood.” And according to John Martin, there was the usual row between Jack and Ginger over volume. But for once, Ginger was more the bystander in all this. At any rate, Jack and Ginger walked out on stage for the encore; Gary walked out of the building with John Martin. They finished up at the nearby Groucho Club. And so it started.

However, for the most part, when they were on the stage BBM absolutely tore places apart – they were a superb live act and fulfilled all the promise of Jack’s 50th-birthday concert. Gary especially enjoyed the gigs they did in Spain: “They were the best ones. We got into jamming a lot in the Cream tradition – it was a very magical band.”

Once John had taken over as manager, he brought in Ian ‘Robbo’ Robertson as tour manager. An ex-member of the parachute regiment, Robbo had already acted as security for the Natural Law Party Albert Hall concert. That night, he had roped in a friend of his, another ex-serviceman and a full-time fire officer, Darren Main. Looking back, Robbo says, “I think the greatest service I did for Gary was to employ Darren.”

Darren began as security for Gary, but quickly became his long-standing multitasking personal assistant, friend and confidant who (a bit like Radar O’Reilly in MASH) knew what Gary wanted almost before Gary knew himself.

Gary acknowledged that for all the extraordinary musical telepathy there was between him and Jack, there was a ‘political’ dimension to their relationship: “You have to remember there were three, not two, leaders in that band. Put them together and it’s very hard for them to compromise beyond a certain level. I think Jack felt it was more my thing and wanted to get back to being in charge of his own music, although I was trying to keep things as equal as possible.

“To be honest, at that time I was probably the most popular of the three of us – I could sell out very big venues all across Europe. I think Jack felt he was being pulled along by me, but I didn’t want it that way at all.”

Putting the politics aside, they were the best of mates. Post-gig, Ginger would repair to his room for tea and a spliff, while Gary and Jack would hit the bars with attitude. Gary: “We’d be sitting in a bar, and some guy would come up and talk to me and I’d just sit there while Jack answered every question, just taking the piss. We’d drink brandy and get really pissed and he’d suddenly say: ‘Shall we go home?’ And it was like four in the morning.”

Although in truth they never went anywhere in the end, except back to their hotel.

When Gary talked about flying home, he made it sound like he and Jack surfed the net, booked some tickets and off they went. But this was 1994, so no online booking, and they certainly weren’t going to plough through all the flight schedules bound in huge paper timetables, working out how to get home and back again for the next gig.

As tour manager for BBM it was up to Robbo to make sure that the demands of these performers were dealt with as best as he could, and most tour managers can take this kind of left-field request in their stride. By his own admission, Robbo wasn’t that experienced and maybe didn’t yet have the rhino hide you need for the job. “You’ve got to be a complete asshole to do that job and you cannot let all the shit get to you,” says John Martin. As Robbo admits: “That BBM tour was the worst of my life. There were nights on that tour when I was on my own in my room in tears.”

Nevertheless, the tour carried on. Plans and budgets were drawn up for a US tour, with some lucrative opportunities in the offing, but eventually the band ground to a halt because much of the latter part of the European tour was blown out by Gary, who said he was having ear problems.

“We tried all sorts of things,” says John. “I talked to Pete Townshend about it, audiologists, we tried new attenuators.”

Ginger was fairly fed up, complaining that Gary continued to play at full volume and then cancelled gigs because of ear trouble. They also had to pull out of the Le Zenith gig in Paris because Gary said he had damaged his finger on a dry-cleaning staple. Jack found this a bit odd: “I’ve played with fingers hanging off, you know. Gary was very insecure on stage. He wanted a rehearsal for the gig at Brixton Academy, and Ginger was furious because he didn’t want to rehearse and blamed me. I could hear him coming down the corridor, shouting: ‘I’m gonna kill that Jack Bruce!’ But Gary had insisted.

“He kept a lot of things to himself, even with me. We had some really good conversations, but he never really opened up and it seemed important that he kept these things to himself.”

There was certainly one thing that Gary wished he could have kept to himself, something that added hugely to the toxic mix of ego, emotions and politics that engulfed and finally sank BBM. On November 23, 1993, The Sun and the Daily Mirror exposed Gary’s affair with the Moore family’s former nanny.

Despite all the hassles, Gary said he took nothing but positives away from playing with Jack and Ginger. He regarded the latter as “the finest drummer I ever played with… they both helped me to be a better player, for sure. They changed my rhythmical feel [and like the blues guys] taught me to lay back a bit more and not be so frantic.

“Jack is one of the few people I would call a genius. I was crazy about his solo albums. Phil [Lynott] and I used to listen to Songs For A Tailor [Jack’s first solo album, in 1969] all day long. The music he was coming out with was just astonishing, so other-worldly. Nobody was writing music like that. He made it flow so beautifully melodically. I was quite in awe of him.”

With the collapse of BBM and also his marriage, it was hardly surprising that Gary pretty much disappeared off the scene for the best part of a year, although he must have taken some heart from the results of Guitarist magazine’s 10-year anniversary readers’ poll in 1994, spanning the decade, which awarded him third place in Best Album for Still Got The Blues; second spot in Blues Guitarist, behind Stevie Ray Vaughan; an overall third in the guitar slot, behind Vaughan and Clapton; and third in Best Act, behind Pink Floyd and Queen.

As there would be no second album from BBM, there was talk of a Gary Moore ‘best of’, which, John Martin says, was originally conceived as a four-disc box set going right back in his career. “And we tried to get a release on Checking Up On My Baby and Going Down, which was done with the Stones on National Music Day.”

This never happened, and the box set idea was scrapped, to be replaced by 1994’s Ballads & Blues 1982-1994. The album title made it plain that this collection was not majoring on ‘Gary Moore, fret melter’, but whatever Virgin’s commercial thoughts might have been behind the release it was a useful reminder to the record-buying public of Gary’s track record as a soulful songwriter. In retrospect, it began to lay the ground for Gary’s excursions to come in uncharted waters.

Taken from the brand new official Gary Moore biography I Can’t Wait Until Tomorrow. Only available in the forthcoming BMG Gary Moore: Blues And Beyond box set. Pre-order now.