This article originally appeared in Classic Rock Presents: Rush - Clockwork Angels

Geddy Lee is seated at the main mixing desk in the Jim Henson Studios in Los Angeles, where the band have come to finish Clockwork Angels. He leans back in his seat as producer Nick Raskulinecz stands next to him. Both are staring at the massive speakers attached to the wall, as if they can see the sounds emanating from them. As The Garden builds and falls in a wash of orchestral strings, Raskulinecz raises his hand dramatically, as the song hits some invisible point, and then stabs at a button on the desk. After the huge wall of sound that’s been vibrating through the room, the silence is startling. “You see?” asks Raskulinecz. Lee nods. He does, apparently.

Twenty minutes later we’re walking down the hallway through the studio’s labyrinthine maze of corridors and ante-rooms. Along one wall stands a half dozen identical old tape machines, all seemingly in perfect working order. Out of a door to our left walks Alice In Chains’ Jerry Cantrell. He shakes Lee warmly by the hand and, for some reason, pats Classic Rock genially on the back.

“Let’s do this outside, it’s a beautiful day”, says Lee, heading to the sunlit courtyard. He points out Charlie Chaplin’s footprints embedded in the concrete – Chaplin originally built the studios and shot both Gold Rush and The Great Dictator here. As we sit blinking in the light, a huge bust of Kermit the Frog bursting through the wall hangs silently over our heads.

Cheerfully, you refer to mixing albums as the ‘death of hope’. Are you ready to give up yet?

We got a few segues left, and that’s it. This last song, The Garden, was a tough mix because it’s such a different song for us, with the textures and the orchestra. Originally we took it in a different direction and it just didn’t have the same continuous feel – it started to feel like it was from a different record, so we took a step back and now I’m very happy with it. This side of the band I’ve always wanted to push more. The melodic side, the orchestration, the possibility of that. I guess you’d call it the softer side, I don’t really see it as that – just more thoughtful, reflective maybe. So I’m really happy the way that turned out.

When word filtered down that you’d made a concept album, our first thought was, ‘Is it going to be 2112 or Fountain Of Lamneth?’

Ha! Caress Of Steel part II! That’s what we’ve been joking about all this time… We keep saying, it’s Caress Of Steel all over again. Get ready for the ‘Down The Tubes Tour’ part two!

Alex said that it would take $1,100 to make another concept record; you said you’d want $10 million in 1970s money, what happened?

One of the great things about this band is that we really don’t know what we’re doing too far ahead; we just let it happen. Whatever’s going to happen happens and sometimes it works well and sometimes it’s a bit sideways and sometimes it’s not so good. But I think that’s part of the journey, right? Someone asked us in an interview, who is Rush? And the three of us just had no answer for him. It’s such a stupid question in one sense, but it also makes you think about yourself in a kind of existential way, and I realised that we can’t answer that question because we’re constantly in search of that answer.

It’s a strange thing to say, but this album really sounds like Rush…

No, I think that’s true. I think this album really sounds like Rush, the essence of who we are. One of the things we agreed upon early was, ‘Let’s write a trio’s album’. We thought we were doing that with Snakes & Arrows, but we didn’t; we just made that record a little too dense. Going in to this, we wanted to have moments where it was just the three of us playing the way we play on stage. We had so many amazing jams last tour, like in Working Man, where we allowed ourselves to free form a bit. We enjoyed it so much that I said to the guys after the tour, ‘Let’s try to be that band sometimes on the next record’. It feels so essential and it’s what we’re about.

It sounds as though (producer) Nick Raskulinecz only encouraged that.

Yeah. We’re a bit curmudgeonly, you get tied to your way of doing things, so it’s hard to break out of that. But with a producer like Nick that has that kind of enthusiasm and confidence and also knowledge, it works. If any old person came in and started asking us to do some of the things he asks us, I don’t think we could pull it off. But because we know where he’s coming from and we know that he understands… For instance, he can sing you every note of every drum lick, you know. He’s coming from the same place that we’re coming from as musicians – he is a musician, he’s got legitimate respect from us – so when he comes in the studio and asks us to try something else, we look at each other and go, ‘I don’t know about this’. We think for a second, and we respect the guy, so we do it.

Plus, Neil has been really open to rhythmic ideas from outside, a lot more open generally. Alex and I put together rough drum ideas when we’re writing, and Alex is brilliant at creating rhythms, and so sometimes Neil will just use it, when it’s right it’s right. Same thing with his approach to Nick this year: rather than go through the whole process of writing the song and then having Nick come in and push him around, he let Nick push him around first.

You’re singing a lot more on this record, too.

It’s just where we’re at. The lyrics and the music we were writing lent themselves to melody. It was ironic, because in some of the songs where I was feeling a little bluesy, maybe, and wasn’t sure that they were something I could make into a satisfying melody, the exact opposite happened, because it didn’t have so many constraints: because it was a loose, bluesy feel. Like in Seven Cities, I could stretch out melodically, I could be a little more that guy, and it kind of put me in mind of the way I used to write when I was just starting. Everything Rush had kind of begun as a band listening to people like John Mayall; we liked American blues reinterpreted by British rock musicians. That was the thing that turned us on. And it kind of took us back there a little bit.

The songs started coming together over two years ago.

They did. We wrote Garden at the same time as B2UB and Caravan; Anarchists and Clockwork Angels, too, they were all two years ago. I’m the kind of person, when we write something, or even when we record, I don’t listen to it everyday. Alex is the exact opposite: he’s constantly listening to it and driving himself mental. So I didn’t listen to those songs for something like a year and a half, until we went back last September to start writing again. I hadn’t heard them in two years almost, so when I put them on, I was shocked at how well they stood up.

You said that about going back to listen to Permanent Waves.

That doesn’t always happen. You have all these reference points when you’re working on something; the things that bug you and the things that are successful stay with you, so when you’re listening to them constantly, you’re reinforcing either one or the other. When you’ve forgotten about the song, forgotten about what surrounded it, it becomes a new thing again, so you can judge it a lot more clearly. Permanent Waves had shed all those things for me and it sounded great.

It feels like you’ve gone full circle on this album – back to writing together and jamming, extended pieces, more experimentation. Alex says it’s because he’s 58 and doesn’t care what people think anymore.

He looks 58! I don’t know why we took so long to get to that place, you have ways of writing and sometimes you ignore the obvious. And the obvious always comes back to what you are as a band, and we’re players first, always. But somewhere along the way we missed that connection on how that playing informs the writing and that’s a really big part of it. We changed our approach to song-writing and somehow forgot that’s how we used to write in the old days – that that’s how we wrote Spirit Of Radio, that’s how Tom Sawyer was written, all of us together in a room jamming. So without realising it, our playing was informing our writing right from the get go, and then we went away from that. We separated that from what I guess is essentially Rush.

Do you write songs away from Alex and Neil?

I haven’t in quite some time. I did during the period when Neil was on hiatus, shall we say. I did then. I haven’t since.

Why do you think that is?

I think I learned, when I did my solo album [2000’s My Favourite Headache], how much effin’ work it is when you’re doing it outside of a band and playing every role. And so when we got back together, I truly appreciated my relationship with them as band-mates, and I just said I’m not writing unless I’m writing with them. It’s not worth it. It’s just way more fun with them. And the results are way more satisfying.

Do you ever think about making another solo album?

Yeah. I think I would do another solo record. I have some ideas I’ve been working on. I love to play.

You’ve always resisted repeating yourselves; you’ve been quite dogmatic about it at times…

The one thing that Nick has shown us is to not be afraid to respect our accomplishments of the past. And it’s not that we borrow from our past, it’s a different thing. It’s like saying, ‘That’s a thing we know how to do really well’. We spent most of our lives running from anything we’d already done. Some would say it’s not a forward move, it’s a sideways move, but nonetheless we’re trying to learn more, we’re trying to get to a better place finally: to write that song that we feel is better, play those pieces that reflect a growth. You get lost along the way, but that’s what we’ve tried to do.

The Time Machine tour obviously energised the three of you, even if you were worn out at the end of it.

It was just a great experience for me. I think it helps, too, to have children that are a little older and feel a little less guilt about being away from them. I think the time of our lives makes us more appreciative of the positive things that we have. I’ve heard sports guys say this quite often in their last few years, they get invited to an all star game or whatever, and when they were younger, they didn’t really experience it with the same emotion that they do later, and I understand that completely. Now, whenever we hit the stage it’s like an opportunity and I don’t know how many more of those opportunities one has in one’s life. So, I think we all feel kind of privileged and I know that Neil has come to a much happier place about touring and playing live. I think he’s reconnected with that being an essential part of what a musician is. It was torture for him, and it’s still very difficult, just given the kind of person he is, just in his private nature. He’s come to terms with the fact that if you are a musician and you are still wanting to hone your craft, you have to play. It’s just what you do and that’s huge for him and, of course, it reinforces our feelings.

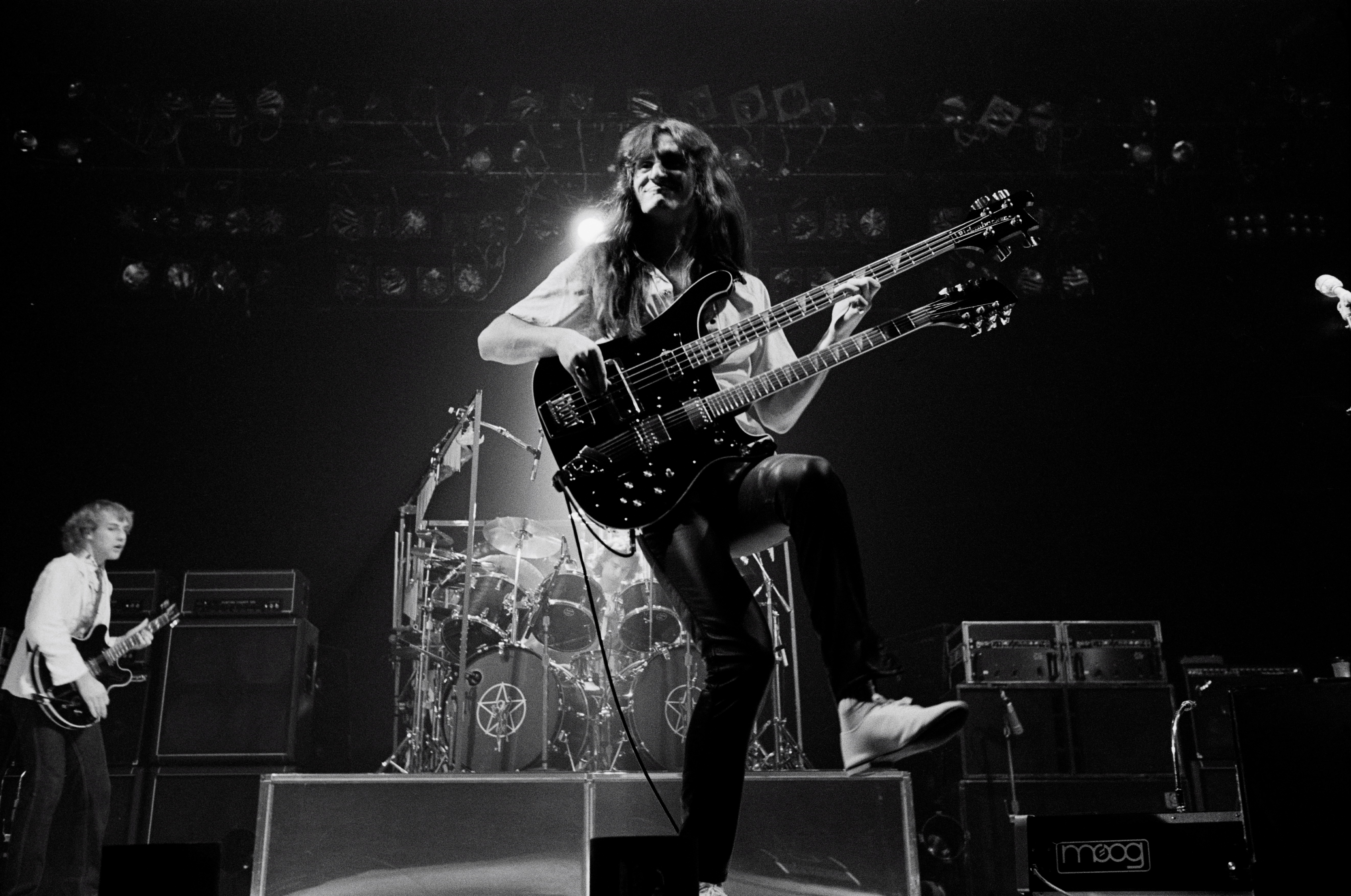

I think that attitude made every night on stage so much more enjoyable, and the way the show was structured was really quite fun, it was really hard. Especially as the tour winds on and you’re running out of gas. But we had those moments – Camera Eye was one of those, and Working Man was one of those moments where you just… You could tell everyone was so into it, in that moment and loving the fact. When you start a tour, your chops are decent, but they’re a little clumsy and we just got our playing to a point where I don’t think we’d ever gotten to before, ever. I don’t think we ever have played with as much confidence and fluidity as we did on that last tour, let’s hope we can repeat it!

- Rush: Neil Peart - Man Out Of Time

- The Prog Interview: Alex Lifeson

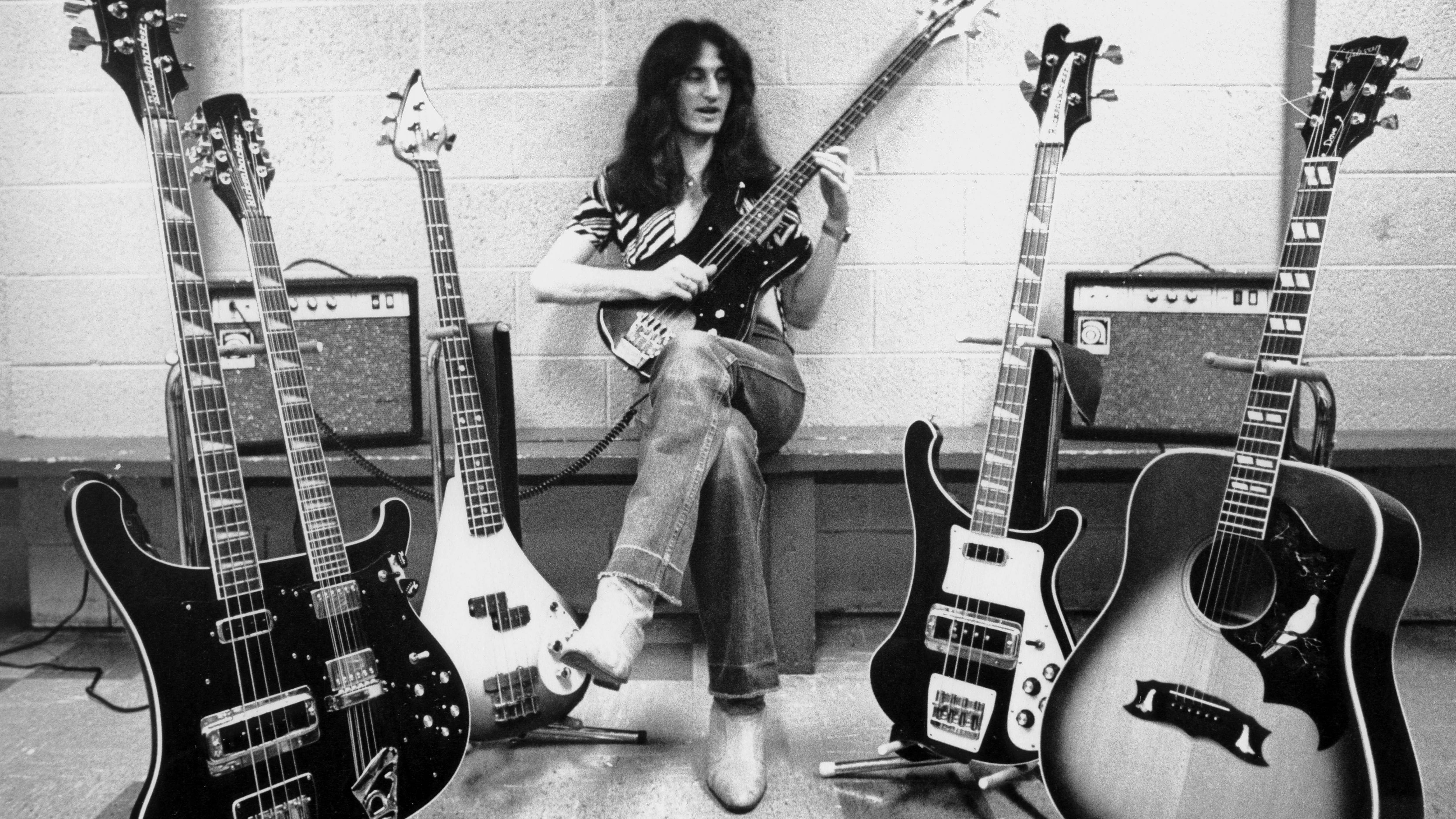

- Heavy Load: Geddy Lee

- Rush accept touring days are over

When we spoke to you in London after the O2 show, you talked about pushing boundaries live… What did you mean?

Parts of the show kept getting better for me, and I felt like we really were playing so well. It got looser and more free, and we were pushing the boundaries and trying to see if we could hit a breaking point almost, just pushing and pushing. It was a great experience, we’re trying to make this next tour a little different, to give people a different experience, slightly.

But it’ll still feature the Time Machine stage set, all the bells and steam whistles?

There’ll be some tweaks. We’ve got lots of ideas. The steam punk thing is definitely part of it, we just jumped the gun. We got excited about it, which is good at our age.

After years of resisting it, you’re finally talking about doing some festival shows.

I think we will do some festivals in the future, because I think it is an interesting way to get across to people who maybe wouldn’t come to the oppressive idea of a Rush show… Three hours of us, some people don’t want that! We played more outdoor festivals on the last tour in North America, and we proved to ourselves that we could do it and still maintain our vibe, our thing. It was just a nice experience, so we’re learning not to be afraid of those. We were such control freaks for so many years: we didn’t want to go anywhere we couldn’t control the environment, put on our show. So we’re learning that wherever we play, that’s our show. And at the end of the day, it’s about the playing, and the songs, and it’ll be fine.

In the five years since Snakes & Arrows your public persona’s changed again, not least because of the Beyond The Lighted Stage movie. People like you guys…

There’s been a huge shift in perception of us, but just because we’re nice doesn’t mean you should like our music. The film is very watchable, it’s got a great pace to it, and it shows up in all these places where you’re trapped, like airplanes or a boring Wednesday night on the movie channel, and people are watching it and they’re finding the story interesting and they’re coming away with a different impression of us. And I see it on the street, I see it wherever I travel… I’m far more recognisable than I’ve ever been. It is what is, there’s good and bad; I can’t accept the good and complain about the bad, that’s my attitude. We get into restaurants a little easier.

Neil’s never seen the movie, but have you watched it again since it was made?

When I came home from this first part of the mixing session after Andrew [MacNaughtan, the band’s long standing photographer and friend] had passed, I couldn’t sleep, and so I got up and was nursing a Macallans, flicking through the channels and I saw it was on. So, and I don’t know why, but I just started watching it. I started seeing things in it that I hadn’t noticed the first time, listening to things a little differently, because when I saw it the first time I really didn’t want to, it was hard to watch. Watching yourself talk about your life, it’s not for me. But I started watching it again and started thinking, my god, how strange to see your life up there on a television show in the middle of the night. And I thought about all the different people that can’t sleep and are having the same experience I am, but they’re watching about my life! It’s just so bizarre.

But was it a good experience?

It was all good. It was interesting to hear everyone’s take on us, the kind of things that the other musicians were saying and how important our music was to them. The stuff we say about ourselves, I hear that all the time. But hearing other people talk about you and seeing what you mean to them…

Hearing Billy Corgan talking about what the song Entre Nous meant to him was actually quite affecting.

Yeah. Billy blew my mind in that. The things that he was saying about his relationship with his mother, and what that song meant to him… And even Trent Reznor, it meant a lot to me to hear those guys talk about our work. Because you don’t start doing this for any other reasons but your own, and, of course, forty years later, you never expected that you’d still be doing it… And then to hear other people describe your work in such a serious light, it just makes you feel like you’ve lived a life, and that’s such a nice feeling. That and getting over the shock that a filmmaker made us interesting…

When you saw the first edit, you and Alex said you liked it, but asked if there could there be less of you in it.

We meant it! Not that they listened.

One revelation in the film is that your longstanding manager, Ray Danniels, fired you and the band went along with it.

He really did! That was pre-history really. We hadn’t recorded yet and were still in our embryonic stage, and he came along. He had no real reputation yet as a manager or anything. He was just kind of an agent working in Toronto back then. So he started directing the band, and he just thought I wasn’t suitable for whatever reasons he had. I don’t know whether it was the way I looked, or my religious background – who the fuck knew? Anyway, he influenced them and they went along with it, Alex and John [Rutsey], and I was out. I was out! They kicked me out!

We were a four piece at that point. My friend Lindy Young – who is now my brother in law, my wife’s brother – he was the piano player in the band, so this is way back, back when we were just playing little drop in centres, that era.

But they basically kicked me out, and I started a blues band, and I was doing gigs and was, frankly speaking, doing better than they were! And then I got a call from John and he said, ‘Can we get together? Basically, can you come back? We’re sorry.’ They had to go through whatever they went through, so we tried it again, and that’s really when the band started. Then we became this three piece, and then we were really going in the same direction.

Sam Dunn from Banger Films (the company who made Beyond The Lighted Stage) says that if you and Alex hadn’t been such outcasts living in the Toronto suburbs, there probably wouldn’t have been a Rush. Fair comment?

I think that’s pretty true. I think it makes you want to escape your surroundings. I think most musicians and artists probably have that in common, where their art is a vehicle for escape from what they believe is a boring existence.

It was certainly that way for me, and I think that’s why a lot of our fans identify with us, because a lot of them are from the suburbs and a lot of them had the same feelings, the same frustrations. And so, to a certain degree, we’re one of those people who somehow managed to get away.

Subdivisions crystallises those thoughts into five minutes plus.

On the last tour, Michael Moore came to one of our shows, and we found out that he’s a big Rush fan. He was saying that very thing to us about Subdivisions, and he quotes Subdivisions at the top of his last book. And I thought that was fascinating, because I have a lot of respect for him and I love what he does; he’s smart, and a moral guy. So Neil says to him, ‘Oh yeah, which line?’ And he put the poor bugger right on the spot and Moore’s going, ‘Oh… I…’, and he’s sweating and trying to remember exactly which line he used. I just wanted to grab Neil and shake him. Put the guy on the spot or what?!

Your audience really spans generations now: you’re talking to dads and their kids these days. That must be a thrill?

It really is amazing, I love it. There’s dad and mom and the two kids, and why does that kid not have earplugs on? Why is that guy holding a baby up? Put the baby down! Leave the building with the baby immediately! There are about six people every night that I want to scold – what is wrong with you? This is cruel and inhuman treatment of children!

Talking of cruel and inhuman, you’ve recently told right-wing American firebrand Rush Limbaugh to stop using your music on his radio show.

I didn’t know he was using our music. Apparently, he’s been using Spirit Of Radio for quite a few years; we didn’t know that. I wouldn’t know where to find his radio show, he’s such an offensive human being; I try not to bring that into my life. Anyway, this gentleman who worked for The Huffington Post wrote to us and made us aware of it.

We had a similar thing happen with Rand Paul, the Libertarian candidate – he’s like a Tea Party guy, he’s Ron Paul’s son – earlier this year. We heard he was using our music on his campaign and actually quoting lyrics of ours, and we sent him a nice letter saying, ‘Please don’t do this’.

I don’t want to be seen to be sponsoring these guys. A lot of situations you can’t control how your music’s used. You don’t want to get caught up in it too much, but some people put you in a position where you have to separate yourself from it.

On a happier note, your baseball team, the Toronto Bluejays, play Spirit Of Radio through the PA each time they score. Which isn’t so often…

I like that. Sometimes the players choose their walk up music and this catcher, who I’ve since got to know, Gregg Zaun, he’s now retired from the game, but the one experience I had, I came to the game and it was the first time in a while. I’d been on tour for most of the season, and they played Limelight as he came on deck circle, and then he hit a home run. So he walked round, and as he was coming back, he pointed at me as everyone applauded. That was kind of a sweet moment I won’t forget.

Something else the film turned up was your room filled with baseball ephemera at home. You just picked up a signed Fidel Castro ball, didn’t you?

I did, yeah. No one goes in that room apart from me. I started collecting baseball stuff about twenty-five years ago. I stopped for a while, because things were getting really outrageous. When I started collecting, it wasn’t such a big deal to buy somebody’s signature. But with the boom of the 90s it got crazy; all these new millionaires were looking for things to collect: wine went crazy, collectibles went nuts, so I kind of came out of that. But in the last few years I’ve got interested again, because the upside of having a boom market is stuff comes out of the woodwork. So I started noticing rarities that I’d always wanted and had no access to: game balls, different players that you never thought you’d see on a single signed baseball, the kind of thing that was inherited within a family and they now realised they could make a few thousand dollars from it. So it helps them, and then it goes into my glass case.

You’ve bought the film rights to a book about baseball; you’re in the movie business now.

Yeah! It’s called Baseballissimo, written by a guy called Dave Bidini. It’s non-fiction, and we’re kind of fictionalising it, we’re taking a lot of liberties with it. I’ve known Dave for a long time; he’s a musician who played in a band called The Rheostatics. Actually, he knew Neil long before he knew me. He went off to live in Italy in order to write the book, and he came back a year or so later and I was so thrilled to read what he’d come up with. I found it to be such a charming story, about something that most people don’t realise: that there’s such passionate baseball fans in Italy, and how Italy got introduced to the game through the GIs at the end of World War II.

People love books, it doesn’t meant they have to option the movie rights…

I thought it would make a great film. I have this bugaboo about great Canadian books that get optioned and then made into shitty movies. So I just kept saying to him, ‘Make sure someone doesn’t fuck it up!’ And in the meantime I had been talking to a friend of mine here in LA about turning books into films. I find it really interesting… It’s difficult, more unsuccessful than it is successful. I kind of thought, ‘What’s involved, maybe this is something that I could do?’ I had this conversation with Dave at one point and he was having some difficulty in getting someone interested, and so I started putting people together to talk about it. And Dave called me up one day and said, ‘I want you involved in this project, you speak for this book way better than I can, why don’t you help me get something going?’ Long story short, I optioned the book and together we’ll find a producer and I hope we’ll do it properly.

Will we be seeing a Geddy Lee original soundtrack?

No. It does interest me, but not for something like this. I know Alex has done it numerous times. Plus, he’s a great actor too, he has all those tools at his disposal…

His performances in your short films are nothing short of remarkable.

I always think of the most ridiculous get ups for him: ‘Hey Al, how about you play a real fat guy?’ He really takes to it. [Laughs]

They’re brilliant fun, especially as everyone thinks you’re so po-faced as a band.

Nobody takes the piss out of themselves to the extremes that we do. The first time I saw Jethro Tull was on the Thick As A Brick tour and their production was so much fun. What a lovely bonus to give an audience that’s sitting there for three hours listening to this intense music! And our music is a little on the bombastic side, so I think it’s nice to give some candy.

Which is going some, considering just how serious your fans can be.

They’ve made such a bond emotionally with the music that it’s hard for some of them to take it lightly. Some fans were upset that we were on The Colbert Report and that he interrupted us in the middle of Tom Sawyer. It was funny, and we were obviously in on it, but to them it was sacrilege. Lighten up a bit, would you? We’re just having fun. That stuff’s harder to come by than you might think sometimes.