“After Supper’s Ready, I think we’d always had the idea of one long piece that could carry a whole album,” says Genesis keyboard player Tony Banks, referring to the epic, 23-minute centrepiece of 1972’s Foxtrot album. “You could call The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway a concept album, except that it’s such a dirty word these days.”

Along with The Who’s Tommy and Quadrophenia, David Bowie’s The Rise & Fall Of Ziggy Stardust & The Spiders From Mars, Jethro Tull’s Thick As A Brick and Pink Floyd’s The Wall, Genesis’s The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway is one of a handful of releases that defined the concept album genre.

This sprawling, 1974 double album has been an essential touchstone for those who’ve developed the style over the last 30 years: Rush, Styx, Queensrÿche, Iron Maiden, Marillion and (despite their denials) Radiohead. You can find websites that give a line-by-line an analysis of Genesis’s lyrics and more theories and meanings than you can throw a colony of Slippermen at.

Not that The Lamb… was greeted that way when it was released in late 1974. The story of a Puerto Rican New York punk named Rael and his surreal adventures in the underworld, as told by a bunch of English public schoolboys, did not exactly set critical pulses racing. The dense plot, sprawled across a double album, was impenetrable to many reviewers who decided it was pretentious.

“It got a pretty mixed response in terms of reviews – and from the fans, initially,” Banks remembers. “People tend to look back and see it as the culmination of the early era of the band, but it wasn’t seen that way at the time. It was darker than our earlier albums, and being a double album it took people longer to get into.”

It didn’t even seem that impressive to the band at the time, either. The six months Genesis spent making the album stretched the band to breaking point – and, briefly, beyond. The experience changed them irrevocably, not least when singer Peter Gabriel left the group at the end of a six month tour of America and Europe to promote the record.

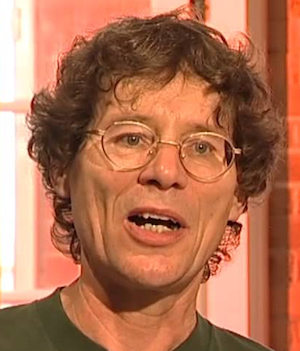

“When it was done I just remember thinking: ‘Phew’,” guitarist Steve Hackett recalls. “Some albums are a natural birth. This one was definitely a breech birth. It came out kicking and screaming, rather than in the tranquillity of a birthing pool in your living room.”

“It didn’t feel like a glorious moment or anything,” Banks agrees. “I was pleased with the album, but it was a rather bumpy ride. There’s a dark edge to the album all the way through, and maybe the fact that we weren’t at our happiest comes across.”

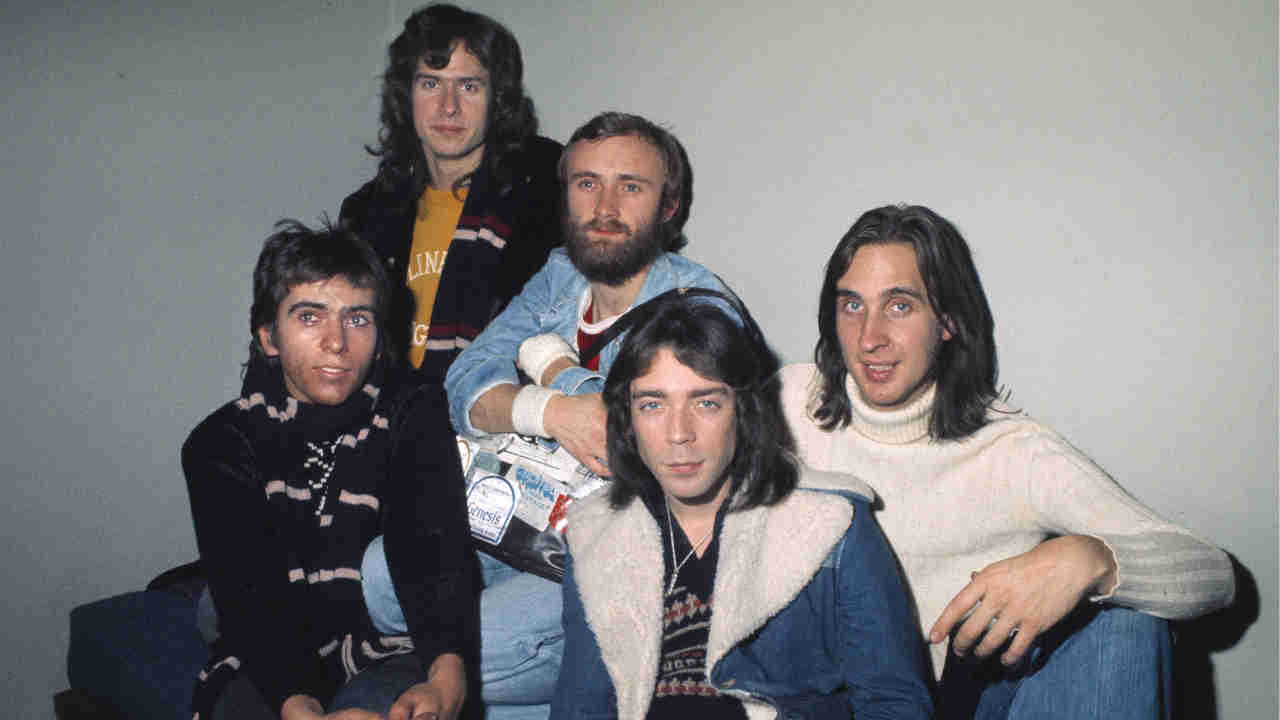

It wasn’t supposed to be like that. In the summer of 1974, when they began work on The Lamb…, Genesis were coming off the back of their first British Top 10 album, Selling England By The Pound, and they had even had a brief flirtation with the singles chart with the quirky but catchy I Know What I Like (In Your Wardrobe), which got to No.19.

Three years of building up a cult audience via their Nursery Cryme and Foxtrot albums and constant gigging was paying off. Genesis were big in Belgium and Italy and had established a bridgehead in America. So there was a mood of optimism when they reconvened after a break to

consider their options for the next album.

“To begin with we were pooling material in the way we normally did,” Banks remembers.

The idea of devoting a whole album to a single story had, as he says, been in the back of their minds for a while. Once that had been agreed, the band’s internal democracy required that individual ideas had to be submitted for band approval.

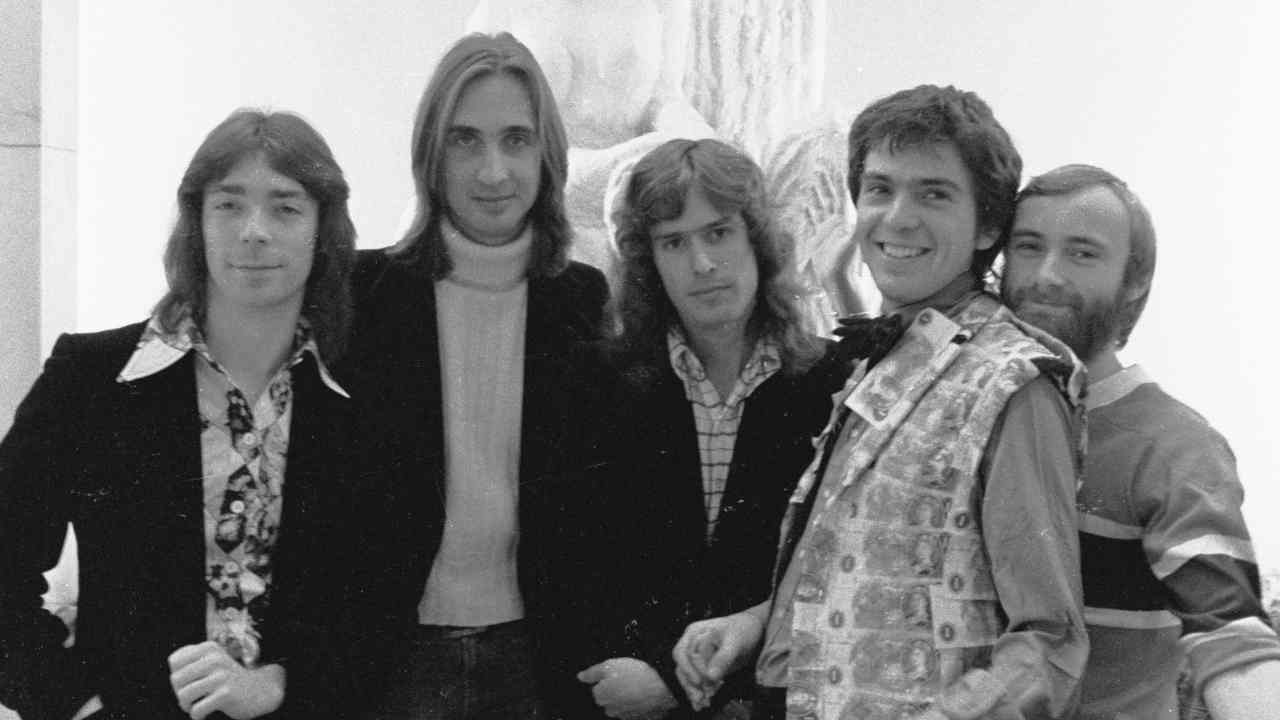

This democracy had produced a group dynamic that was different from most other progressive bands at the time. Unlike Yes or ELP, Genesis were not about instrumental virtuosity or flash showmanship. “We were very much a composers’ group,” says Banks. “We were interested in the song and the way that it came across. Even when one person was leading it on vocals, keyboards or guitar it was still very much a band thing.”

As Steve Hackett puts it: “We were less about heroics, and more about illustrating stories.”

Peter Gabriel already had a story for the new record: “A type of Pilgrim’s Progress, but with this street character in leather jacket and jeans,” as he describes it. “It was looking more towards West Side Story as a starting point. I knew mine was the strongest, and I knew it would win,” he recalls. “Or rather, I knew that I could get it to win.

“The only other idea that was seriously considered was an adaptation of The Little Prince [a modern French fable about love and loneliness, by Antoine de Saint-Exupery], that Mike Rutherford was in favour of. I thought that was too twee. This was 1974 – it was pre-punk, but I still thought we needed to base the story around a contemporary figure rather than a fantasy creation.”

Once Gabriel’s story idea had been accepted, he then proceeded to break the democratic rules by insisting that he should write all the lyrics. “My argument was that there aren’t many novels written by a committee. I said: ‘This is something that only I’m going to be able to get into, in terms of understanding the characters and the situations. I was indirectly writing about my own emotional experiences, and I didn’t want anyone else colouring it.”

The others were not happy. “It didn’t go down very well with the rest of the band, to be honest,” says Banks. “We’d always written the lyrics between us. And I still feel even now that it would have been a better album if other people had been involved as well. It was a fairly fragmented concept. There was scope for lots of things that other people could have done.”

But Gabriel was insistent, and the others, realising that this could become a sticking point, gave way. “It seemed fair enough,” Hackett remembers. “We all wanted to be a band, and we were prepared to make that concession. It was all very gentlemanly, as I recall. There were no big arguments at that point.”

The band moved down to Headley Grange in Hampshire to work up the album, free from distractions. Headley Grange had already staked its claim in rock’n’roll history as the place where Led Zeppelin recorded Led Zeppelin IV; Robert Plant even recalls writing Stairway to Heaven with Jimmy Page by the fireplace in the sitting room. But the place was a mess.

“It was in a pretty revolting state when we got there,” says Banks. “I think Bad Company had been in just before us. The only permanent residents were the rats, and they used to use the wisteria outside as a staircase.”

“Robert Plant always thought it was haunted, Hackett says. “I used to hear these scratching noises in the night. I thought it was the rats. But there was certainly a depressing aura hanging over the place.”

There’s no shortage of people trying to make two plus two equal five where Led Zeppelin and bad vibes are concerned. But any bad vibes lingering over Headley Grange probably date back to 1830, when it was trashed by a gang of agricultural labourers during a riot. The miscreants were rounded up, seven of them were transported to Australia and two others were hanged at Winchester Prison in front of the other condemned prisoners. So maybe it wasn’t just the rats…

Nevertheless, Genesis settled into Headley Grange, and Banks, Hackett, Rutherford and Phil Collins started working on musical ideas while Gabriel beavered away at the lyrics in another room. Banks was aware that this creative separation had created a division within the band.

“Once Pete was saddled with the lyrics, he took less part in writing the music than he might have done,” he says. “Most of the music was written without any lyrics. We’d write bits to illustrate various parts of the story. Some of the more experimental ideas like Fly On A Windshield and atmospheric pieces like Silent Sorrow In Empty Boats were just improvisations that we could edit into shape later.

“The first time we played the Evil Jam, which became The Waiting Room, we turned down the lights in the room and tried to frighten ourselves. And the first time we did it we really did frighten ourselves. It had a real dark edge to it, and the whole gloomy atmosphere of the house seemed to come out. We were all excited by it. But unfortunately we didn’t tape it, and every time after that we were chasing an idea. The final result was okay, but it doesn’t have anything like the strength of the original.”

Phil Collins also remembers the Evil Jam: “It started with Steve inventing noises, and Tony messing around on a couple of synthesisers. We were just mucking about with really nasty sounds. Peter was blowing his oboe reeds into the microphone and playing his flute with an Echoplex, when suddenly there was a great clap of thunder and it started raining. We thought: ‘We’ve got in contact with something heavy here.’ We were making all these weird noises, when the thunderstorm started and it began to pour down. And then we all shifted gear and got into a really melodic mood. At moments like that it really was a five-piece thing.”

Mostly on the album, however, it was a four-piece thing and a one-piece thing. “Peter was writing the story, and little bits were being revealed to us as we were going along,” Hackett explains. “But I don’t think we were really working on the same page. The album was heavily conceptual, but I don’t think we realised how much at the start. For all we knew he could have been writing individual songs on a theme.”

Hackett had his own problems to deal with as well. “I was separated from my first wife and was in the process of getting divorced. And I was living with the band in this derelict, depressing house. The band was also pulling in different directions. I thought our playing on Selling England By The Pound had been very good – quite clever, in fact – and there was humour. Even John Lennon liked it. What better testimony can you have? And now we were doing The Lamb…, which seemed much more dense and claustrophobic – the whole writing environment and everything.”

Gabriel was feeling distracted too. And not just because his wife was pregnant. “Around the time we started work on The Lamb…,” he explains, “I had this call from Hollywood from William Friedkin, who’d seen the story I’d written on the back of our live album and he thought it indicated a weird, visual mind. He was trying to put together a sci-fi film, and he wanted a writer who’d never been involved with Hollywood before.”

Friedkin was hot property in Hollywood at the time, having just made The Exorcist, and his interest was clearly flattering for Gabriel: “I would bicycle down the hill to the phone box and dial Friedkin in California, with pockets stuffed full of 10p pieces.”

How much the rest of the band knew about this intrigue at the time is unclear, but when Gabriel told them he wanted to take some time off they were annoyed. “The group was very much the main thing in our lives at that time,” says Banks. “If you’re going to do it properly, there’s no way one person can suddenly go off like that, leaving the rest to hang around for three months. Peter kept saying that if this William Friedkin offer came he would do that in preference to working with us. And I thought: ‘This is absurd.’”

“If you push Pete into a corner, he will retreat still further,” says Mike Rutherford. “When we tried to tie him down he became more and more vague. Then he went off back home to Bath.”

“Obviously we didn’t want Peter to leave, but he was being quite – how shall I say? – a little obstinate about it all,” says Banks. “And we thought, to hell with it. We definitely wanted to carry on. We were going to write another story line. We’d already written a lot of good music.”

Hackett remembers discussions about recruiting another singer. When the band’s management and record company found out what had happened, there was pandemonium. The boss of Charisma Records, Genesis’s label, rang Friedkin and told him he was responsible for breaking up the group. Friedkin backed off, leaving Gabriel in the lurch.

“Our manager, Tony Smith, came down and said to us: ‘I think we can get Peter back. Are you all interested?’ And we said yes,” says Hackett.

Mike Rutherford was appointed the go-between. “I rang Pete and said: ‘This is silly. Come back and we’ll sort it all out.’”

Gabriel: “I had said: ‘If you’re not going to allow me to do anything else, then I’m not going to stay.’ And Mike had replied: ‘If you delay the project, then we can reach an agreement.’ In a sense I’d won that round, but the resentment which had already accumulated became even more pronounced.”

Banks: “It made us realise that it could happen again. We were still very intense at that age, and the fact that Pete wasn’t 100 per cent into it any more changed the whole group dynamic again.”

Hackett reckons that, mentally, Gabriel left the group at this point. Other pressures were also coming to the fore. They’d written plenty of good music, and the concept had grown into a double album. But Gabriel was already behind with the lyrics. And they were running out of time at Headley Grange, which had been booked by another band.

They decided to relocate to Glosspant (since renamed Glaspant) in the wilds of Cardiganshire, a village so remote it made Headley Grange seem like it was in the middle of, well, Broadway. “It was okay. Not brilliant. It was just converted outhouses really,” Banks recalls. “But we quite liked the fact that we were completely away from everything. And we liked the idea of using a mobile [studio].”

But whereas Headley Grange had proven recording credentials, with Led Zeppelin, Glosspant was more problematic. “It had been sound-proofed to some extent, but there was a bit of a buzz on everything,” says Banks.

Scarcely had they settled in at Glosspant than Gabriel’s wife Jill went into labour. It was a long and difficult birth, and their daughter spent the first few weeks in an incubator, in a critical condition.

“My baby daughter was between life and death in Paddington,” Gabriel recalls. “So there was this five-hour drive to visit my wife and baby. My wife hadn’t been allowed to see the baby for the first few days because they thought she wouldn’t survive – something they would never do now. It was the most traumatic thing I’d experienced in my life.

“The rest of the band were sympathetic, but they couldn’t understand. And ‘the band’ had always been ‘the boss’. Our life was our work, and any kind of life outside this all-consuming entity was something the others found pretty threatening.”

But the band were already locked into a schedule that was over-running. Dates were being booked for a US tour at the end of the year. As Hackett says: “What we should really have done at that point is stop. We should all have sat down and talked. Peter could have explained it to everyone. But we didn’t. We weren’t grown up enough yet.”

So the recording continued, along with the tortuous process of matching the music to the lyrics – which still weren’t finished. “In the end Mike and

I did write one lyric – for The Light Dies Down On Broadway – to speed things along,” Banks says.

There were also a couple of extra tracks needed to fill gaps in the storyline. The first was the quirky Grand Parade Of Lifeless Packaging. “We had nothing written for that, and it developed out of a little idea I had,” says Banks. “It was intentionally humorous, and Peter came up with a lyric that took it even further. I really like it because it’s much more spontaneous than the rest of the album.”

The other was the gorgeous Carpet Crawlers. “That came fairly late on,” Banks remembers. “Pete already had the lyrics, so Mike and I sat down and wrote a chord sequence and Pete created a really nice melody on top. That again was spontaneous, but it ended up being the most popular track on the album.”

“I always thought that melody was one of choicest things I’d written,” says Gabriel. “To me, it was a pop song.”

Hackett, meanwhile, recalls having to find his own space in the song (as was often the case): “Mike’s finger-style 12-string, Tony’s piano arpeggios, together they created a lovely, shimmering, cloudy sound. There was nothing much I could add to that. So I started providing a counterpoint to Peter’s vocal. It’s a difficult melody to begin with, but it turns into a great melody. I don’t think there’s been another song quite like it.”

By the time they got back to London for the mixing sessions at Island Studios, things were fraught and frazzled. Phil Collins remembers mixing the album in shifts: “I’d be mixing and overdubbing all night, and then Tony and Mike would come in and remix what I’d done, because I’d lost all sense of normality by that point.”

For Gabriel, “the only way I could work was to go into a corner and function on my own. A lot of the melodies were written after the event – after the backing tracks had been put down.”

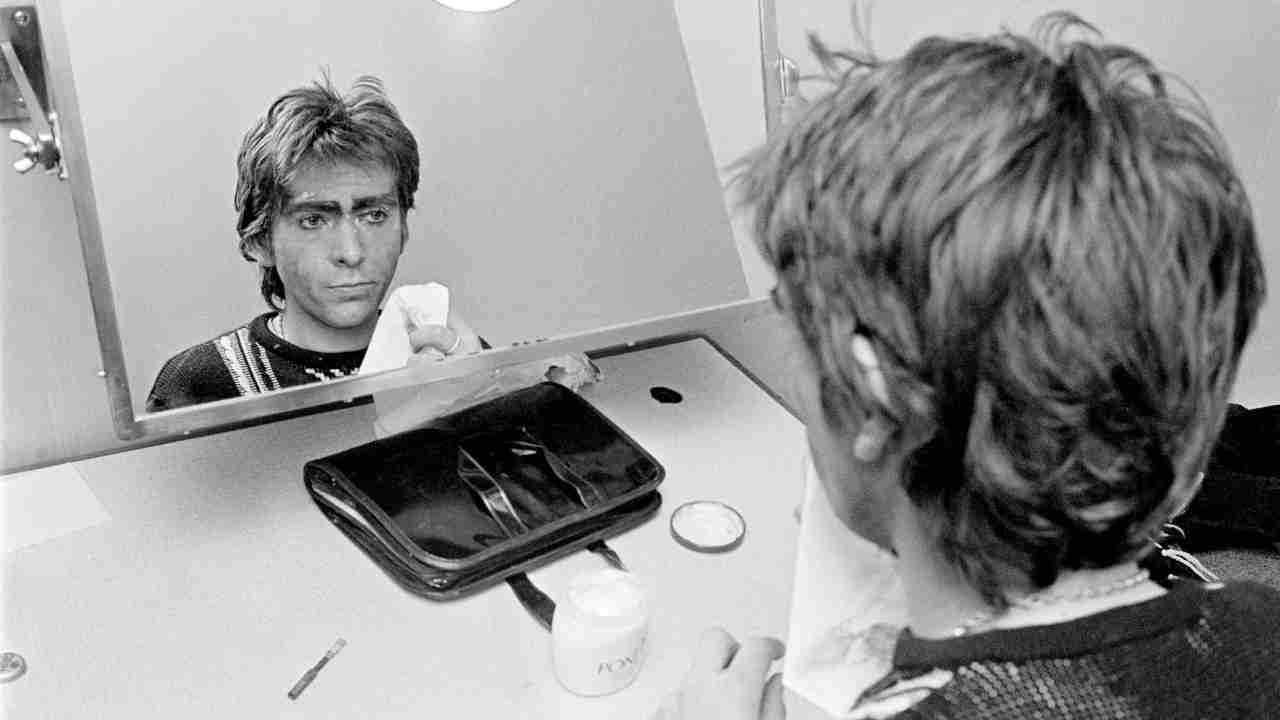

Despite his self-imposed isolation, Gabriel made friends with Eno (the ex-Roxy Music synthesiser player/‘electronics’ man who was now enjoying a solo career), who was working in the studio upstairs, and ended up getting ‘Enossification’ on his vocals for Grand Parade Of Lifeless Packaging and In The Cage.

Producer John Burns (who had also worked with the band on Selling England By The Pound) struggled to keep the final mix under control as tired hands pushed the faders all the way up. “We were all playing enough to fill the sound on our own, really,” Banks admits. “We were also trying to get as many ideas down as possible. I think that’s why it sounds a bit dense.”

When The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway was finally finished, they had left themselves no time to prepare for their tour, which would consist playing the whole album. The blessing in disguise that enabled them to postpone the tour sums up the state the band was in.

“I was at a reception after a Sensational Alex Harvey Band gig at the London Palladium, and I had a glass of wine in my hand,” Hackett explains. “It was not my first. I was telling someone I thought the Alex Harvey Band were terrific, and he said: ‘But they’d be nothing without Alex.’ The next thing I knew I’d crushed the glass in my hand. I’d almost cut my thumb off.”

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 89