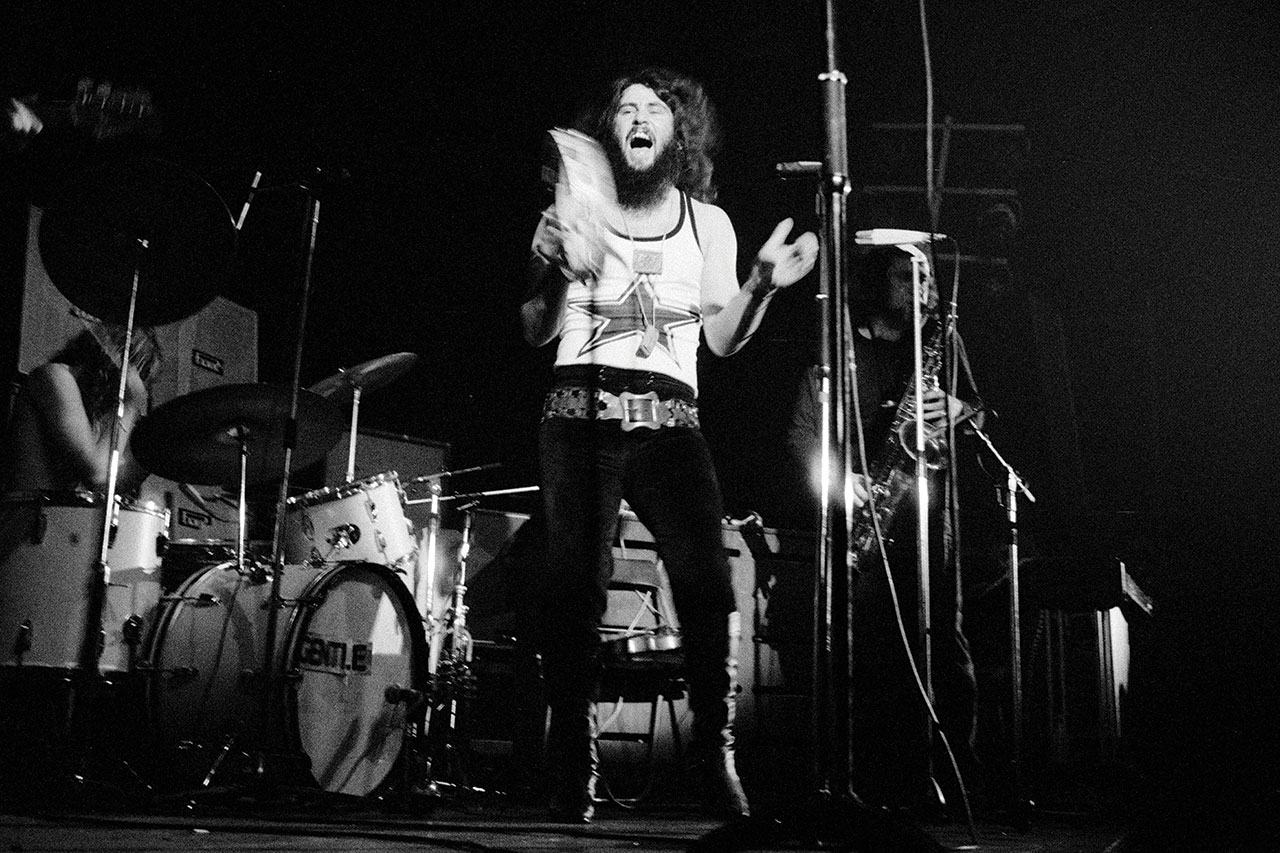

Once the taste has been acquired, Gentle Giant are one of most flavoursome bands in prog. For those who like their music in turns spicy, delicate and super-literate, they remain arguably the genre’s best-kept secret.

Yet 37 years since their demise, the whispers are getting louder. They have a significant, and growing, hardcore fan base of admirers. One of the first acts to spawn a cottage industry for reissues at the end of the 20th century, they have since been keenly championed by Steven Wilson, who has remastered several of their albums. His latest is one of his best for them: Three Piece Suite looks at the cream of the group’s first three releases.

We here at Prog have long recognised their significance – they picked up our Lifetime Achievement Award at the 2015 Progressive Music Awards. Lead singer Derek Shulman flew in from the States and joined bassist Ray Shulman and keyboard player Kerry Minnear – half of the original six-piece – to collect their gong that evening.

Almost two years to the day later, coinciding with the release of Three Piece Suite, Prog got wind of a very special event taking place in Portsmouth, the band’s home town, and soon were on a fast train to the south coast. The group – and Simon Dupree And The Big Sound, their hit-making precursors – were being inducted into the Portsmouth Hall Of Fame at the Guildhall, right there in the middle of the city.

It was here in the Guildhall that the Stones, Jimi Hendrix and many others played. Davy O’ List stood in for Syd Barrett when Pink Floyd played here in 1967, and it was where Dark Side Of The Moon was first played in its entirety five years later. It was here, too, that a 12-year-old Derek Shulman bunked off school to see The Beatles, but was caught in the queue on a Southern TV news bulletin that got him in trouble.

At a beautifully organised and tremendously sincere event, the brothers who founded Gentle Giant – Derek, Ray and, most importantly, Phil Shulman – were together, along with founder member Kerry Minnear. This was huge news as Phil, the eldest brother and the group’s original visionary, now a very spritely 80-year-old, hadn’t been in the same room publicly with his brothers since 1973. Although Gentle Giant were to play the hall twice themselves in ’74, and ’75, Phil had long left the group.

Surrounded by the extended Shulman clan, it was like being at a sizeable family wedding: children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren mingled with cousins, wives, nephews, nieces and old friends from the Portsmouth music scene. Even Tony Ransley, the drummer from Simon Dupree, was there.

Gentle Giant join a Hall Of Fame that already includes other well-known exponents of Pompey showbiz, Edgar Alan Poe, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Joe Jackson, Mick Jones from Foreigner and Mark King (from the Isle of Wight).

After the ceremony, Prog enjoys an exclusive audience with Gentle Giant. The repartee is priceless. At the start of our interview, we discuss Phil being back in the fold for the day and, just as Prog says, “Which is…” Derek chips in with “very sad” and Ray retorts simultaneously with “historic”, which offers a remarkable insight into the fraternal dynamic of the band. Phil jokes that he feels something of an imposter in the city as “I live in Gosport”. A cursory look at a map will tell you it’s less than two miles away.

We were initially to talk about the three albums Gentle Giant, Acquiring The Taste and Three Friends from which Three Piece Suite is made, but on returning to London, we felt we should expand our article to include their ground-breaking fourth album Octopus, and assess Phil’s years with the band as a whole. Calls were made to Wales, America and Sussex and soon our Giant tale was complete.

Hear how their first four albums – lauded, loved and, in their original Vertigo pressings, extremely collectible – are the gold standard in progressive rock, and marvel as Simon Dupree And The Big Sound, Phil, Derek and Ray, were in the clubs one moment, then on Top Of The Pops. Next, they’re touring Scotland with the future Elton John as their keyboard player, then – as Gentle Giant – they’re playing with members of the Royal Academy Of Music and being produced by Tony Visconti. It all happened very quickly. In fact, it all seemed a bit like a fable…

In the early 60s, it seemed unlikely that the Shulmans would enter a Hall Of Fame, or that Portsmouth, a vital but somewhat unloved hub on the UK’s south coast, would consider opening one. The Shulman family had relocated there from Glasgow in the late 1940s. Their father, a professional musician (and sales rep by day), had been posted there during the war and realised that he wanted to move his family out of the Gorbals.

The three Shulman brothers grew up in a very musical household: youngest Ray recalls learning the trumpet at the age of five, and the violin two years later. Phil, the eldest brother, was born in 1937, eye-wateringly prehistoric for pop, and was a jazzer.

After teenage bands the Howling Wolves and the Road Runners, the brothers morphed into Simon Dupree And The Big Sound. Derek, the lead singer, ‘became’ Dupree.

Signed to the Arthur Howes Agency and EMI, the group were on package tours and moved quickly away from their R&B roots after hitting the post‑Pepper UK Top 10 in 1967 with the pop-psych novelty Kites.

From then on, as the group chased another hit single, the returns diminished. After one too many cabaret appearances, in 1969 the Shulmans decided, as was the mood of the times, to head in an altogether jazzier, proggier direction.

“There was this whole change in the air anyway,” Ray explains. “As Simon Dupree we played a gig with Cream in Bournemouth.”

“We blew them off the stage,” Phil says. “There was a big cultural shift in the 60s. We were that generation. The first thing Cream said when we came off: ‘What are you on, lads?’ Nothing – we were just a sweaty band.”

“Jeff Lynne was in the Idle Race, Robert Plant was in the Band Of Joy, Robert Fripp in the League Of Gentlemen,” explains Derek. “We were all going through a similar thing: people started to move away from pop music.”

The brothers – who soon dispensed with most of the rest of the Big Sound – had a champion in manager Gerry Bron, who put them on a weekly wage, with a road crew to build their dream. It was Bron, too, who was instrumental in their new name: “Colin Richardson, a wordsmith who worked for Gerry, titled us,” Phil recalls. “‘You play gently and you play loud: Gentle Giant.’ At first I cringed: it sounded like someone selling sweetcorn.”

“We were putting the music together,” Derek says. “We said, ‘Call us what you like!’”

The Shulmans, along with Southampton-based drummer Martin Smith, who’d graduated from the Mojos to the Big Sound, needed some like-minded souls to accompany them on their journey. In early 1970, they were to come across Minnear by chance: “Kerry’s arrival was very important to us,” says Ray.

“My house was a student house and a big lad from Kerry’s school in Dorset said that he knew someone who was in a band and that the poor bastard was starving,” Phil says. “I told him I was interested. When he mentioned the Royal Academy, I thought, ‘Well, he can’t be half bad.’”

Minnear had graduated from the Academy with a degree in percussion. He had joined a band called Rust, and had been stranded in Germany when the group imploded. “I got a phone call out of the blue,” he recalls. “I brought Eric Lindsey from Rust with me, as I heard they needed a guitarist.”

Minnear was in. Lindsey – who now owns a music shop in South London – was not. “We told Kerry he was a great player but a crap talent scout!” says Phil.

Minnear relocated to Portsmouth and stayed with Phil and his wife Roberta for the next six months. “I wrote a lot of stuff there,” he says.

A regime was established that was straightforward. “We were writing and rehearsing,” Derek says. “Rehearsing all day and every day.”

The next giant step for the band was to get a guitarist, and so they duly placed an ad in Melody Maker. In March 1970, 19-year-old blues player Gary Green was the 45th person they saw. Green was dazzled by their professionalism.

“It was another world for me – they had these guys at their beck and call,” he says. “Martin Smith stood up and motioned he needed a cigarette, and Frank [Covey], the roadie, lit one and gave it to him. There was all this equipment: two 4x12 stacks for each player. I was a little bit intimidated: it was only the cannabis that kept me sane!”

He impressed the others as he was the first guitarist to tune up. “Gary was such a blues player,” says Ray. “Steve Hackett is not a blues player, he plays his lines like a classical guitarist. That was what made us unique.”

After a subsequent audition, Green was in, staying with Ray in Portsmouth as the band continued rehearsing and beginning to play shows – their first at the city’s poly in May was billed as ‘Gentle Giant featuring ace singer Simon Dupree’. The Dupree moniker would never fully leave Derek Shulman. “I was a pop star,” he laughs. “I still am.”

“He used to say, ‘Call me Simon,’” says Phil. “Oh, he was Simon.”

“I still am Simon,” Derek retorts.

Brothers in pop are never the easiest of bedfellows. This billing must have been the sort of thing that caused a rift between them? “Of course!” Derek replies, relishing the moment.

“In one interview I was asked: ‘What’s it like having a famous brother?’” says Ray.

“I was never that comfortable with it,” says Derek. “I had the two brothers behind me going, ‘Yeah, right, you’re Simon! That brought you back to earth!’”

And ‘down to earth’ they remained in 1970, as the gig was poorly attended, but it didn’t stop them taking support slots and, importantly, playing, playing, playing.

When their much-loved debut album was released, producer Tony Visconti wrote a suitably in-era sleevenote about the group getting their heads together in their country cottage, taking you very much into their world. The truth, of course, is a tad more prosaic. “That was the time people were retreating to the country,” Minnear remembers.

“We retreated to a pub!” Ray laughs.

Gentle Giant set up camp at the Cambridge Arms, just off Portsmouth’s Commercial Road. The band formed a tight-knit community. “After living with Kerry and Lesley, Derek and I had a flat together for about a year,” Green recalls. “We used to go bait digging and fishing; we really were in each other’s pockets. It wasn’t that we’d just see each other in rehearsals – we’d pop round, go for a drink, a curry afterwards, rush home to see Monty Python. I also stayed with Derek, Ray and Phil’s mum, Becky: they’d bought her a terrace out of the proceeds of Simon Dupree. She’d cook up Arabic rice for everybody.”

The band soon became a much in-demand support act: “You use what you’ve got. Kerry and Ray were very good musicians,” Phil recalls. “Derek and I were very good showmen. On stage, we could turn something round by a grimace, or a gesture. There was a showbusiness schtick in us. Certainly an energy.”

This showmanship would see them open for most of the prog hierarchy of the day, and to herald their first time at the Marquee, they supported Slade.

It was time to capture the material they had been stockpiling, and so the band went to Trident Studios in August 1970 to cut their self-titled debut. “Gerry Bron suggested Tony Visconti to produce,” Derek says.

“He lived in a scruffy little flat in Putney,” Phil remembers. “We used to stay on his floor.”

Visconti was another jobbing producer then: The Man Who Sold The World had just been released, but the whole T.Rex explosion was yet to happen. “Mick Ronson and Woody Woodmansey – the guys from Hull – used to turn up at Trident,” Phil adds.

“I think Bowie turned up once, too,” says Derek.

“We didn’t shoo anyone away,” says Phil.

Visconti had a fan in Gary Green: “I thought he was a little bit of a magician. He was a really good musician, and he really understood what we were doing.”

Among the album’s seven tracks that showcased their versatility, there was Funny Ways, always a group favourite, which highlighted their delicate, madrigal-influenced side, while the stomping Why Not? blared their hard-rocking intent. Nothing At All was their first truly standout track, moving from floating CSN-style vocal harmonies – learned while the Shulmans were in Simon Dupree – mixed with Minnear’s off-the-wall Cornelius Cardew‑influenced musicianship.

“The first album was the stage show, which is why there was a drum solo,” says Derek. “You don’t do that on an album for the most part.”

“Like it or not, it was still rock’n’roll that had to be performed,” adds Phil.

Gentle Giant appeared with little fanfare in November 1970. With its sleeve designed by David Bowie’s school friend George Underwood, it was melodic, quirky and loaded with gravitas.

“People said Gentle Giant didn’t do that well, but it did okay,” Derek says. “It certainly wasn’t a big chart burner, but it got our name on the map and enabled us to make another record.”

Visconti was to return for the next album, too, recorded at AIR and Advision in the first months of 1971. Acquiring The Taste, released that July, has become the connoisseur’s Giant album. “I love Acquiring The Taste, I love the atmosphere of it. It feels so ethereal; it’s a magic noise,” Green says.

“We’d never played any of those songs live,” Ray says. “We did a lot of experimentation; it was very much a studio record.”

“It’s a moody album,” Phil adds. “If you look at the lyrics, you can’t pin down what it’s about. I went through an art book and got ideas from that – The Moon Is Down, for instance: the moon doesn’t come down, the moon goes up! It’s a surreal album. I really like it. Black Cat was a tribute to William Blake’s Tyger Tyger Burning Bright.”

It was these concepts that set Gentle Giant apart. Phil, who’d taught art at Eastney Secondary Modern Boys’ School, was full of ideas and happy to put them into songs. And, of course, there were a lot of references to giants.

“François Rabelais [author of the Gargantua And Pantagruel series of novels], the giant bit, I read that before it was popular because it’s filthy! I looked for anything coarse! The warm goose neck, a wonderful way of wiping your arse. I tried to turn that into a song.”

With its sleeve a reference to licking the backside of the music business, there was a factor at play that similar prog groups didn’t have: cynicism.

“The Shulmans had one bite of the apple, but now they wanted a bigger one,” Green recalls. “Phil certainly had his eyes wide open about this ruthless, cut‑throat business. He wasn’t gonna let naivety through the door, and we’d got the thick skin.”

“People were now getting intrigued by whatever the hell it was we were doing,” says Derek.

There was someone who wasn’t intrigued, however. Gerry Bron decided amicably to move on. “Gerry hated Acquiring The Taste,” Ray says. “Well, he would!”

“He didn’t know what to do with it, did he?” Minnear reveals.

“He was having success with Uriah Heep, more traditional rock groups,” Ray explains. “I think he thought after our first record, we’d go more in that direction.”

In came World Wide Artists (WWA), the father and son team of Pat Meehan Snr and Jr to look after the group’s affairs. Derek and Phil constantly looked for opportunities to build the group’s success: one of the first things WWA did was to look at better exposure for the group in America. They signed to Columbia, as the Meehans understood the size and scale of the market.

There was to be another change – drummer Martin Smith was out. “Martin’s playing was a bit ‘tappy’ for Phil,” Green recalls. “Martin loved traditional jazz – if he’d been offered to play with Kenny Ball, that would have been his gig.”

An advert was placed in Melody Maker, and Malcolm Mortimore was selected. “Even though I was just 18, I’d been playing the drums for a little while,” Mortimore says. “I was in Train with [future Damned guitarist] Brian James, who’d opened for King Crimson. I was keen to get out in the biz.”

After an audition at the Roebuck pub, in Tottenham Court Road, and a second in Portsmouth, Mortimore received “a telegram from World Wide Artists informing me I had got a place in the ‘very talented musical group called Gentle Giant’. That’s when I knew who I’d joined.”

“Malcolm played incredible stuff,” says Green. “Everything, all the time, all in one song. He was the best of the bunch.”

Mortimore went down to Portsmouth and slept on a mattress on the floor at the Minnears’ home. After a week’s rehearsal, Giant were out again playing shows, supporting Jethro Tull in Europe. “We were well-received,” Mortimore recalls. “They loved the grandiose nature of it all.”

It was also time, thanks to their incredible work ethic, to return to the studio. The time with Visconti had been pleasurable, but, as Green says, “We could produce ourselves. Anything went.”

It cemented the close relationship with engineer Martin Rushent who, a decade later, would be the feted producer of the Human League’s Dare.

“We became really chummy,” Green continues. “We just fell into lockstep with him – he was as mad as we were.”

After the Tull shows in January 1972, the group began sessions for Three Friends, a concept album about schoolmates taking different paths in life, at the recently opened Command Studios in Piccadilly.

One of the key songs on Three Friends was Peel The Paint, which includes a three-minute improvised drum and guitar solo from Mortimore and Green.

“Phil told Malcolm to ‘Go out there and make a noise,’” Green recalls. “We both played at the same time. I’d borrowed Mike Ratledge’s Echoplex [Green’s brother Jeff was a Soft Machine roadie]; it was totally improvised. We had an outline – start loud, get a bit quiet and then end up loud. That was as far as it went.”

“It’s a nice little album,” says Minnear.

“People were listening in,” adds Phil.

Mortimore began adapting to the group’s funny ways: “There was a lot of sibling rivalry. Phil, the older brother, was our kind of gangmaster in a way. Derek was the singer and had a lot to say for himself. Ray was gentle, the youngest, nearest to my age. There was obviously a dynamic between the three of them that I just did not understand.”

“It’s funny really, Phil. Did we disagree at any time?” wonders Derek.

“Not a lot,” Phil replies.

“Ray was the peacemaker,” says Derek. “Phil and I were at each other’s throats all the damn time!”

“It was always like the Marx Brothers,” adds Green. “They were indeed huge fans. Phil would always talk about Marx Brothers movies.”

In March 1972, Mortimore was involved in a serious motorcycle accident. “I broke my arm and leg, and cracked my pelvis. I was lucky I didn’t total myself.”

A tour was pending and so a replacement was needed. After considering ex-King Crimson drummer Mike Giles, Ray called up recent Grease Band drummer John ‘Pugwash’ Weathers. When in Eyes Of Blue, Weathers had supported Simon Dupree in South Wales in 1966 and they’d stayed in touch. In 1970 they’d shared a bill when he was playing with Graham Bond.

“I went down to Portsmouth for a knockabout. They liked it and offered me the job temporarily,” Weathers recalls. “It was pretty obvious that I could pick up things quickly. After a couple of weeks, they asked if I fancied taking it on.”

“I went to see them,” Mortimore says. “I was in a wheelchair. They were keen to keep working, keep as tight as they could. Phil called me up and said ‘Malcolm, I’m sorry to say this, you’re fitting in really well, but John’s got to stay.’ I said, ‘Alright, that’s it’ – they were off to America and that was that.”

Like Phil Collins in Genesis, Weathers was ideal for Giant. The band were booked to promote Three Friends in the US, but prior to that, WWA had got them the strange gig of supporting the new Jimi Hendrix film, Jimi Plays Berkeley, around the UK.

“We’d do about 40 minutes, clear the stage, the screen would come down and they’d show the film,” Weathers recalls. “It was a very strange setup. But after we’d seen the movie once, we didn’t need to hang around.”

WWA also looked after the interests of Black Sabbath, and Giant often supported Ozzy’s legendary crew. “We were plonked together with Sabbath a fair bit,” Minnear recalls. “It was an odd combination, but I think it did us more good than harm in the long run in terms of exposure.”

“Black Sabbath had their portentous opening music – whenever they’d hear that, the Shulmans, especially Phil, would sing ‘one meatball and no spaghetti’ – they had a very dry sense of humour,” remembers Mortimore.

On August 24, 1972, Giant began a North American tour with Sabbath. “The only hangover from Simon Dupree was stagecraft,” Ray recalls. “A Sabbath audience was not a Gentle Giant audience. But I think we knew how to sell it, almost by exaggeration in a way: you will like this because we are performing it like this. We were never being serious musos – ‘Look at our virtuosity’ – it was always a question of, ‘We’ll entertain you, so you’ll enjoy it.’”

There was one notorious night at the Hollywood Bowl on September 15. “All the Columbia hierarchy were there,” Derek recalls. “Before we went on, I got into a row with a bloke who said I was looking at his girlfriend, and he sprayed a water pistol at me.”

“I said we should extend the things like Peel The Paint, and do about four numbers, real heavy stuff. But oh no. We thought, ‘This is Los Angeles, they’ve got to be broad-minded musically.’ Wrong!” says Weathers.

The audience could take no more madrigal: at the start of Funny Ways, firecrackers were thrown onstage. “One almost blew my shoes off!” Phil recalls. “I asked 15,000 people for a fight.”

“It was what you called them…” Minnear says.

“A bunch of cunts?” Phil says.

“They sat quite quietly,” Minnear remembers. “It was my teacher’s voice. ‘Now don’t do that again!’”

“We finished the set,” Weathers says. “That was about the worst reception we ever got.”

Their next US tour with Yes and the Eagles was another strange experience. However, redemption was to come in the form of the final American jaunt of the year, back again with Jethro Tull, a simpatico band and audience.

“We were very compatible,” Weathers says. “We’d go down an absolute storm – they were perfect for us, as that was the music that the audience were there for.”

Recorded at Advision at the end of July 1972, Octopus was released that December. From its eye-catching Roger Dean cover onwards, it set the bar high for what prog rock should be: complex, intelligent, with a warm heart. What made the album so different? “Me!” Weathers laughs.

Minnear agrees: “John’s solid approach changed the way we sounded as a band and the way we wrote. We could be more rhythmically adventurous with such a strong foundation. We were settling into our identity as a band and what characteristics were unique to us.”

Weathers introduced Minnear to James Brown’s music. “I played him Sex Machine and he thought it was brilliant, because he got it – suddenly, he just took off on it and started writing all these beautiful rhythmic pieces and doing all the clavinet stuff. Although he had a degree in percussion, he couldn’t rock!”

“In the end, of all the albums we released, the cutest songs are on Octopus,” Phil says.

“It was the zenith of Phil’s time in the band,” Derek says.

“I think Octopus as an album sounds confident both in the playing and in the way its recorded,” muses Minnear. “Even if the original idea of a concept album based on the characters in the band – a bit like Elgar’s Enigma Variations – didn’t materialise, each track seemed to develop confidently in its own right.”

“John’s drumming makes the music appear – and I say ‘appear’ purposely – simpler,” says Green.

“Octopus was heavier prog, as it were,” Weathers says. “We were rocking a lot more. Kerry and Ray had come up with some very good tunes, some good ideas from Phil.”

“The lyrical content fitted the music absolutely brilliantly,” says Green. “I’d heard some of Yes and Genesis – they were too far out for me. We all liked something a bit more real that you could get your teeth into – we were a bit more of a working-class prog band than the others. Even though we had highfalutin concepts: RD Laing, Camus and Rabelais, they made more real-life sense to me. We were a bit more down in the dirt.”

As 1973 dawned, and the release date loomed for Octopus in America, the single most significant shift in Gentle Giant’s decade-long history occurred – Phil Shulman, ideas man, gangmaster, left the band. Of course, it wasn’t just music – it was family too. Today, Phil is reflective: “It’s done. It’s history.”

“To tour, and to record, took an immense amount of time and energy and forward thinking,” Derek says. “It was very difficult for Phil.”

“Believe me, had I been a single man, it would have been a different situation altogether,” Phil says. “But I wasn’t, and I had to remind myself of that.”

“It was difficult for him and it was difficult for us, but the fact is, we decided to continue, even though it was tough for Ray and I – this is our brother,” Derek says.

“We were very unsure if we could continue,” Ray adds.

“We were pretty close,” says Phil.

“We are again now,” says Derek.

“His wife was in her 30s, with two young children,” Weathers says. “He was homesick, whereas we were all in our mid-20s. Phil, being 10 years older, didn’t have what the Welsh call ‘hwyl’ – a mood, a fervour to be on tour. Phil had said he was thinking about leaving, then he didn’t, then he said it again, and didn’t.

“When we were on our Italian tour, Pat Meehan Snr got Phil in and said that we’d had enough – ‘Are you leaving or are you not!?’ Phil said, ‘I’m leaving.’ Pat said goodbye and that was that. He didn’t have any chance to change his mind. Derek and Ray had their heads in their hands. We still had the writers – what was the point in finishing?”

“Phil was the first director of the band – he established its moral authority,” says Green. “We made the bulk of the sound, we were the noise. We became a harder-edged band.”

There’s no doubting the importance of Phil Shulman to Gentle Giant. In a way, his work was done. The band returned to work quickly: by March they were back on the road in America, promoting Octopus.

“I’m naturally quite lazy so when Phil left, I probably moaned inwardly that I would now have to learn to play the missing trumpet and sax parts on one of my seven unpredictable keyboards,” Minnear suggests. “Phil was missed as a lyricist and general ‘envisioner’. We got on with the job of writing In A Glass House in the same manner as previous projects, by me and Ray writing music and sharing ideas and Derek getting involved with vocals and lyrics as things moved along.”

“We were all young, all out there and enjoying it all,” Weathers says. “Derek was now the leader of the pack: we used to take the mickey out of him something terrible. He used to take it all so seriously at times!”

Poised to make headway in America as a five-piece, and depart from Vertigo, that’s where we wind up our tale. So, on reflection, how were the first 25 months of Gentle Giant?

“As a band we were possibly at our most comfortable and stress-free, and looking back through rose-tinted glasses, I’m pretty sure we were a happy bunch,” Minnear concludes.

“We weren’t chasing anything – we just wanted to do something a bit different,” Derek adds. “Did we want to make a living? Yes! Did we want to be really big? Of course! But it was more than that. We enjoyed composing, playing and learning music. We were surrounded by great players and learning all the time. Even in the times when supposedly the albums became more pop, we were still learning.”

Ah, the time when the albums went pop – but that’s another tall story, and one that we shall tell at some point in the future…

Three Piece Suite is out now via Alucard. See bit.ly/gentle-giant-official for details.