George Murray, one of the most enigmatic figures in a David Bowie story that’s been told and retold countless times, was plucked from relative obscurity in September ’75 to apply his singular bass-playing skills to Golden Years.

Providing a pivotal sonic bridge between the slick Philadelphia soul of Young Americans and the harsher rock-literate funk of Station To Station, Golden Years gave Bowie his twelfth UK Top 20 hit single and, over the next four years, Murray was a central cog in Bowie’s rhythm section (the so-called D.A.M. Trio with drummer Dennis Davis and guitarist Carlos Alomar) underpinning Station To Station, its subsequent Low/‘Heroes’/Lodger Berlin Trilogy, Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps), ’76 and 1978’s Isolar and Isolar II world tours, and Iggy Pop’s transformative, Bowie-produced ’77 post-Stooges ‘comeback’ album The Idiot.

At this point, Bowie was arguably at his peak, embracing myriad new sounds and new styles, consuming and reconstituting hitherto alien musical genres into visionary, punk-adjacent, future-proof pop. Inveigling - alongside Brian Eno - ambient electronic music into the heart of the mainstream, and making the role of Thomas Jerome Newton his own in Nicolas Roeg’s film The Man Who Fell To Earth.

Nothing appeared to be beyond late-70s Bowie. But, as George Murray found to his ultimate cost, Bowie harboured one crucial character flaw: he was more than a little deficient in the field of human resource management. Specifically, the hiring and firing of staff.

“What drew me to the bass was the magnetic nature of early rock’n’roll,” Murray begins. “I started developing a fascination with music when I was a young teenager. I was infatuated with it. But when I first started out I wanted to be a drummer.”

Murray took drumming lessons but “couldn’t possibly afford the kind of kits the Dave Clark Five and The Beatles were playing on TV. There’s no way that I’d ever be able to get one of those by shovelling snow and cutting grass. So I bought a bass.”

Cobbling together a rig composed of a Hagstrom early issue short-scale bass and a Guild Thunder bass amp “with two twelve-inch speakers and a little head on top that looked like a robot”, George (carted around by his parents), rehearsed and gigged in and around New York City with various band line-ups, gradually honing his craft.

Eventually, as is so often the case in such stories, destiny came calling. While speaking to a former Western Union work colleague, he was asked: “Do you want a gig?” Soul singer George McCrae (hot from having sold 11 million copies of his ’74 debut single Rock Your Baby), needed a touring band. Murray auditioned, was accepted, and within 48 hours was out on the road. From a Toronto debut, through two European tours in a Volkswagen bus, to South America, Murray, “acting like a brat”, earned his touring spurs before being finally disgorged into the humdrum reality of home.

Back living with his parents in Queens, he decided to go back to school. Following an unsuccessful audition for the Manhattan School of Music on upright bass, he enrolled at Bronx Community College. There, a fellow student recommended he meet Dennis Davis, a drummer of his acquaintance who was apparently “excellent… You’ve gotta play with him”.

“So Dennis and I started playing together,” Murray continues. “And it was through Dennis that I met Carlos [Alomar, guitarist], who I worked with in his band Listen My Brother.”

Listen My Brother were a big deal, early musical regulars on ubiquitous educational kids TV show Sesame Street, and Alomar was connected; he’d been in both The Main Ingredient and the house band at the Harlem Apollo. “I was enamoured of both of these individuals,” Murray remembers of Davis and Alomar. “I liked playing with them, they were good folks and we had fun. I also knew they’d worked with David [Bowie]. This was right around the time of the Young Americans tour [1974].”

When Alomar and Davis returned from the tour (both having played on Bowie’s Young Americans album), “I was playing with them around lower Manhattan and having a grand old time, going to school at Bronx Community College and driving a Yellow cab on the side to make a little extra money. And then, in September ’75, I received a call from Dennis. He said: ‘David Bowie’s looking for a new bass player, are you interested?’ Well, he didn’t have to ask me twice.”

Three days and one long-distance flight later, Murray met Bowie in a rehearsal studio on Cahuenga Boulevard in Los Angeles and they immediately set to work on Golden Years.

“It was a live audition. I wasn’t offered anything except to come and do a few recordings, and that was where we started. Golden Years is still one of my favourite songs. There’s a certain feel to it that’s part of its magic, it just takes you and pulls you with it without being obtrusive, it just grooves along.

"The second song we rehearsed was Station To Station, the actual song, which was completely different from Golden Years and constructed of different parts. When he rolled out its first part, he played the piano chords for about eight measures and gave me the rhythm and timing of the bass line.

“When we finally came to record its rhythm track [at LA’s Cherokee Studios] it was Carlos, Dennis and myself, with maybe David on piano.”

Was Earl Slick there?

“I don’t remember… Anyway, we recorded the whole thing as one piece because that’s the way we rehearsed it. It was three or four movements put together as one composition, a ten-minute song that starts slowly and then takes off. It set the tone for the whole album and the 1976 tour, which it also opened.

"I remember watching audiences with their mouths open as David hit his spot. Setting the stage with a long, drawn-out intro, through the second movement – ‘Drink, drink, drain your glass, raise your glass high’ – and then, as it hit the ‘It’s not the side-effects of the cocaine’ line, all the white lights hit you. It was an amazing piece of music.”

Guitarist Earl Slick revealed that the use of chemical stimulants was a key element of the creative process of the Station To Station album, so might we say that the song itself was a side-effect of the cocaine?

“My experience with cocaine came a lot later, but in all honesty some of it showed up here and there. I don’t know what anybody else’s experience was, but it did take a long time for David to do those rhythm tracks. My experience with rhythm tracks before I did Station To Station were you’d come in, do them and move on. You’d be on a budget and do as much as you could in the time allotted. So five weeks to do six rhythm tracks? That was unheard of for me.

"So yes, there was some partying going on, where cocaine was readily available, but my problems with cocaine started a little later than that, still within the time that I was working with David, but not while I was performing with him. I don’t recall ever performing while being impaired by drugs or even alcohol. Only because what was required of me, to replicate or to create the things that he needed, required all of my attention and creativity.”

Even as the Station To Station sessions drew to their close, Murray remained on his best behaviour.

“As far as I was concerned I was still involved in a live audition, almost all the way to the end of the album, so I just concentrated on whether the bass parts fit together with how the rhythm worked, keeping David happy. I wasn’t making waves anywhere.”

It seemed that no one was ever going to put him out of his misery as to whether he was actually the new Bowie bassist or simply a convenient session player for a single project.

“It eventually became clear that David was happy with the product, and he started talking about a world tour,” Murray resumes. “He’d spoken to everyone but me. I’d heard nothing, neither directly nor via his business manager, and I’m stressed about this."

“One evening an opportunity arose for me to ask Carlos. Now, I’d known since before working with David that Carlos was a practising Buddhist, and the sect he followed was Nichiren Buddhism, the ones that chant ‘Nam-myoho-renge-kyo’ for happiness, individual and world peace, and he told me: ‘Chant these words - “Nam-myohorenge-kyo” - and something will change.’ So I said okay, and in my solitude later that evening started chanting for a few minutes and it felt better, so I left it at that.

“Nothing happened the next day, but the day after, I’m going in one direction and [Bowie’s day-to-day manager] Pat Gibbons is going in the other, and as we passed he said: ‘George, are you doing anything between January and June next year?’ I said no, and he said: ‘Good, David wants you on the tour. So I’ll see you later.’ I was flabbergasted.

“So I started practising more and more, and I’ve continued over the years. And I’d have to say that of all the benefits I got from my six years of working with David Bowie – two world tours, fabulous albums, critical acclaim, a gold record – the biggest benefit of them all came courtesy of that conversation I had about chanting ‘Nammyoho-renge-kyo’ with Carlos. I’ve continued throughout my life and it’s brought me to this point here.”

How was life on the road on the Isolar tour, at the height of Bowie’s fame? What was it like inside the madness? Possibly not quite as mad as one might expect.

“It was structured; you need to do this today, then get up tomorrow and do it all over again. Doesn’t matter what you do in between, but you need to hit your marks. David didn’t fly at the time, so the highest stress came from everyone wondering if the Thin White Duke was going to make it to the show on time, because David would always tell his driver to stop the car whenever he saw any kind of roadside attraction.”

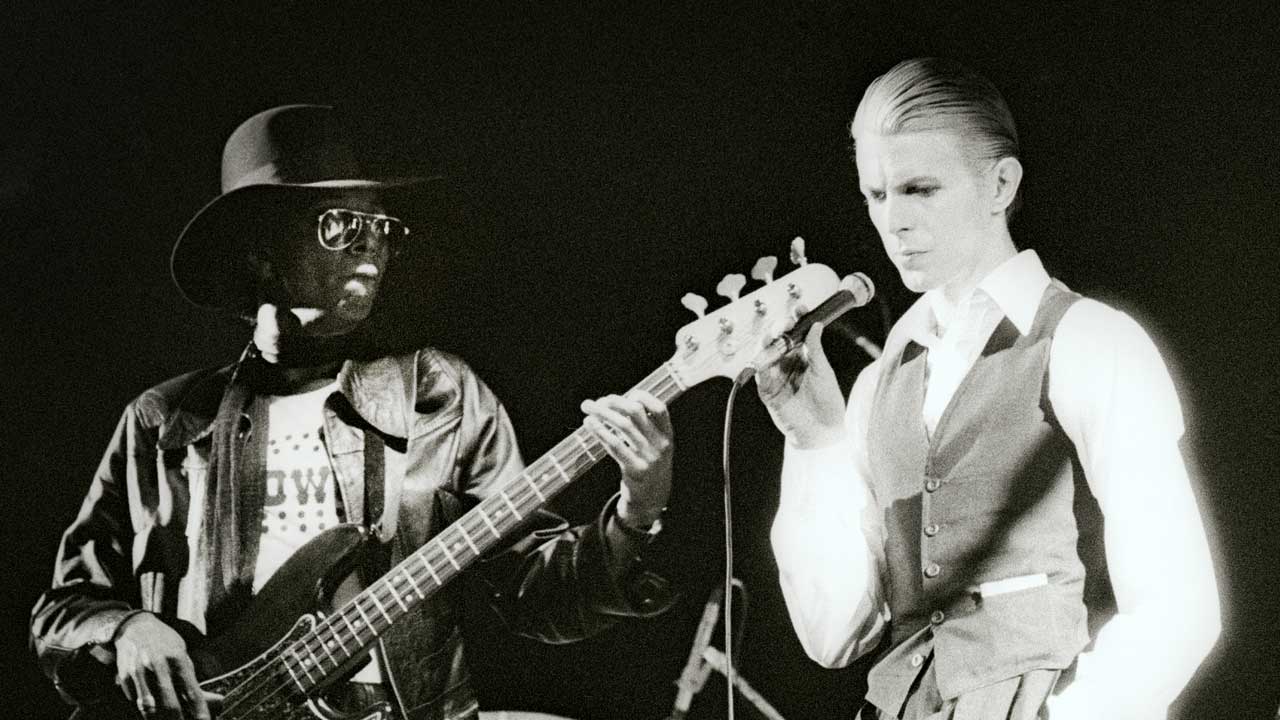

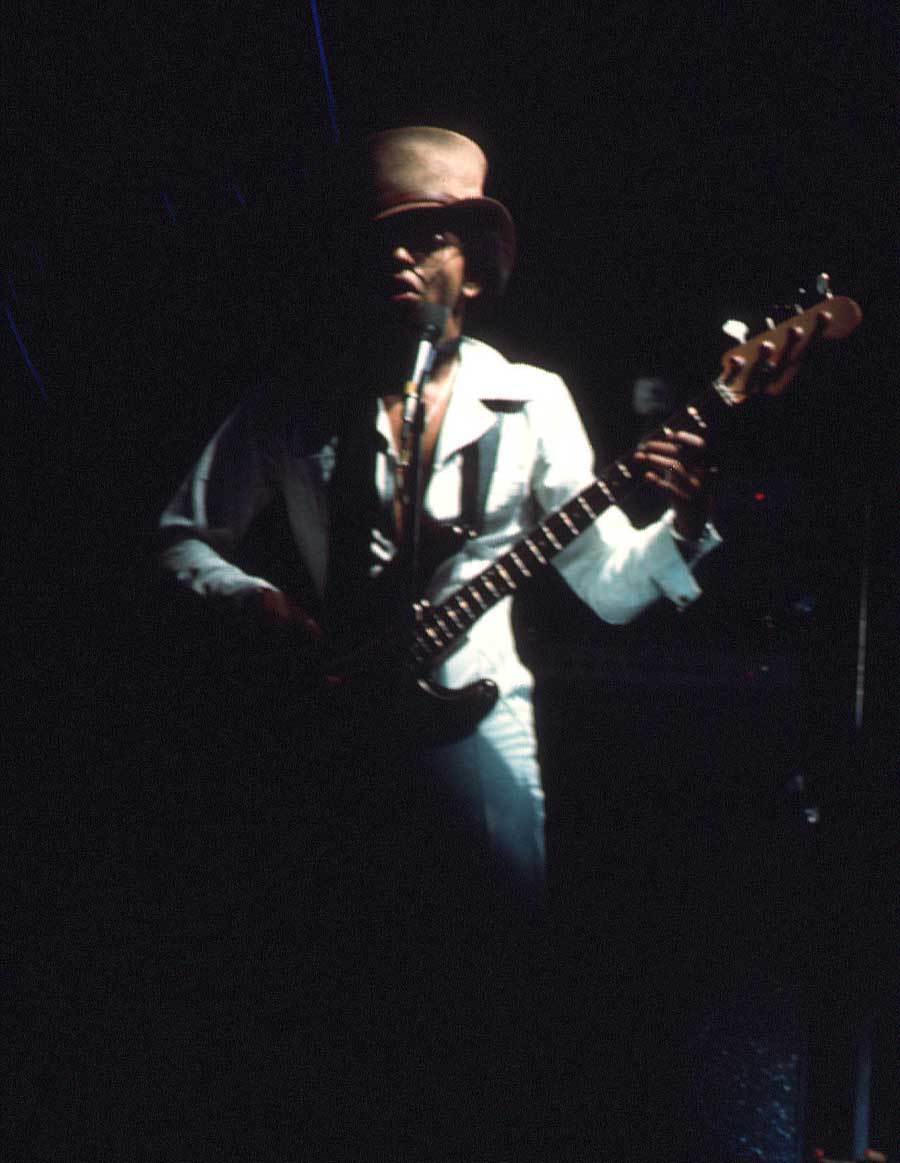

Murray, meanwhile, embraced the tour as an excellent opportunity to explore the more flamboyant end of his wardrobe, wearing a self-styled stage costume that featured both top hat and stack-heeled snakeskin boots.

“Those were actually my stage clothes from George McCrae,” he admits. And what reaction was elicited in Bowie when he first took sight of this near-seven-foot-tall disco-tastic vision? “He stopped dead in his tracks. It was actually on stage, and he just stopped and looked. He eventually kept going, but yes, I do remember that look.”

Following the ‘structured’ excesses of the tour, Bowie’s inner circle (of which Murray was now a fully accepted member) made for Berlin’s Hansa studios, via Château d’Hérouville, France, where work initially commenced on Iggy Pop’s The Idiot.

“We did the trilogy David wanted to do with Brian Eno, which was Low, ‘Heroes’ and Lodger, but, to be honest, I can’t remember recording anything on The Idiot with Iggy Pop. I do remember working with him here and there on some things that David was doing, but I don’t remember that at all.”

One thing that Murray can’t help but remember is the song credit he picked up on Low’s Breaking Glass, which came with certain benefits: “Welcome financial benefits I still get to this day.

“Dennis and I brought the riff to him. It was something that came up during ‘the off season’, which was what we called the time when Dennis and I played together. Dennis thought that rhythm up and said play this, he gave me the riff to perfect, so it was the two of us. Carlos was instrumental, behind the scenes, advocating that Dennis and I should get a credit, so that was Carlos looking out for us.”

Eno arrived into Low’s production process after the backing tracks were recorded, but was present for the entirety of ‘Heroes’, co-writing four songs and employing his infamous ‘oblique strategies’ cards - a pack of instruction cards, which meant creative decisions were occasionally taken more by accident than by design - which would be utilised to an even greater extent for Lodger.

How was working with Eno?

“Whatever the objective was between David and Brian, the direction I took from Brian was challenging, and it took a lot more effort on my part to support it. Not because I didn’t like it, but it was foreign to me. It didn’t come as naturally as direction from David.”

Following 1979’s Lodger and 1980’s New York City sessions for Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps), Murray’s working relationship with Bowie came to an end, but (in much the same way that an interminable live audition drifted haphazardly into his eventual employment) the manner of his expulsion left a great deal to be desired.

“My last experience with David was playing Saturday Night Live,” says Murray. “As I said earlier, my experience with cocaine came years later in my relationship with David. I moved from New York to Los Angeles in 1979, after the ‘Heroes’ tour and Lodger, just before Scary Monsters, and I came as one of those California dreamers.

"I thought I was going to have the same level of success in Los Angeles as I’d had in New York. But that was not to be. I’d acquired bad habits during the years I’d worked with David, and they continued after. It was not a formal end, I wasn’t fired, they just didn’t call me back. I didn’t even get a note from David saying it’s time to move on… It was difficult.”

Murray persisted with his musical career for a while, playing with a number of bands while delivering flowers for a florist, but his past wouldn’t leave him alone.

“My wife used to work at the Westwood Marquis Hotel, and when David was out here for his Serious Moonlight tour [’83], that’s where the band stayed. Anyway, I had to go see her for some reason, and I ended up sharing an elevator with Carlos and Carmine Rojas, the bass player who’d replaced me. Even though it was a heartbreaking moment, I said okay, nice to meet you, and that’s how it ended. My life in music just sort of dissolved from there."

In January 1987, George Murray answered an ad in the LA Times for an entry-level full-time supervisory position at the Alhambra Unified School District, because “I can only do one thing well at one time, and I wasn’t making enough money from making music and delivering flowers to do anything of any consequence with my life”.

After 33 years of putting his “whole heart into managing a crew of young individuals, some of whom were as wild as I was”, raising a son, and being steadily promoted, he finally retired as an Assistant Superintendent in December 2022.

As he ultimately reveals that he’ll be returning to the road in the autumn with the D.A.M. Trio, with Carlos Alomar at his side and an undisclosed drummer standing in for the late Dennis Davis, I ask George if he ever heard from David Bowie again. After a long, telling, 10-second pause, he states simply: “I do not recall hearing from David at all, or being in the same space with David after our appearance on Saturday Night Live. And I do not remember actively seeking him out or trying to make an opportunity to meet with him.”

It should be noted at this juncture that the backing tracks for Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps), upon which, its sleevenotes insist, George played all of the bass parts, were not actually recorded until two months after Bowie’s Saturday Night Live appearance. The side-effects of the cocaine? Well, it should be further noted that early in our encounter Murray offers the disclaimer: “I’m 72 years old, and what I’m telling you is how I remember stuff.”

Finally, philosophically, he concludes: “Going right back to Station To Station, there were times when I could tell Dennis and Carlos were having conversations about the former bass player, my predecessor, and I overheard Dennis saying to Carlos that so-and-so called him again and ‘What do I tell him?’ So I could tell that that individual was suffering because he just didn’t know. And that one day, and I didn’t know when that day would come, I wouldn’t be there either.”