The career of Gerry Rafferty – from folk-roots to multi-million selling success and alcohol-fuelled demise – was one of amazing highs and lows.

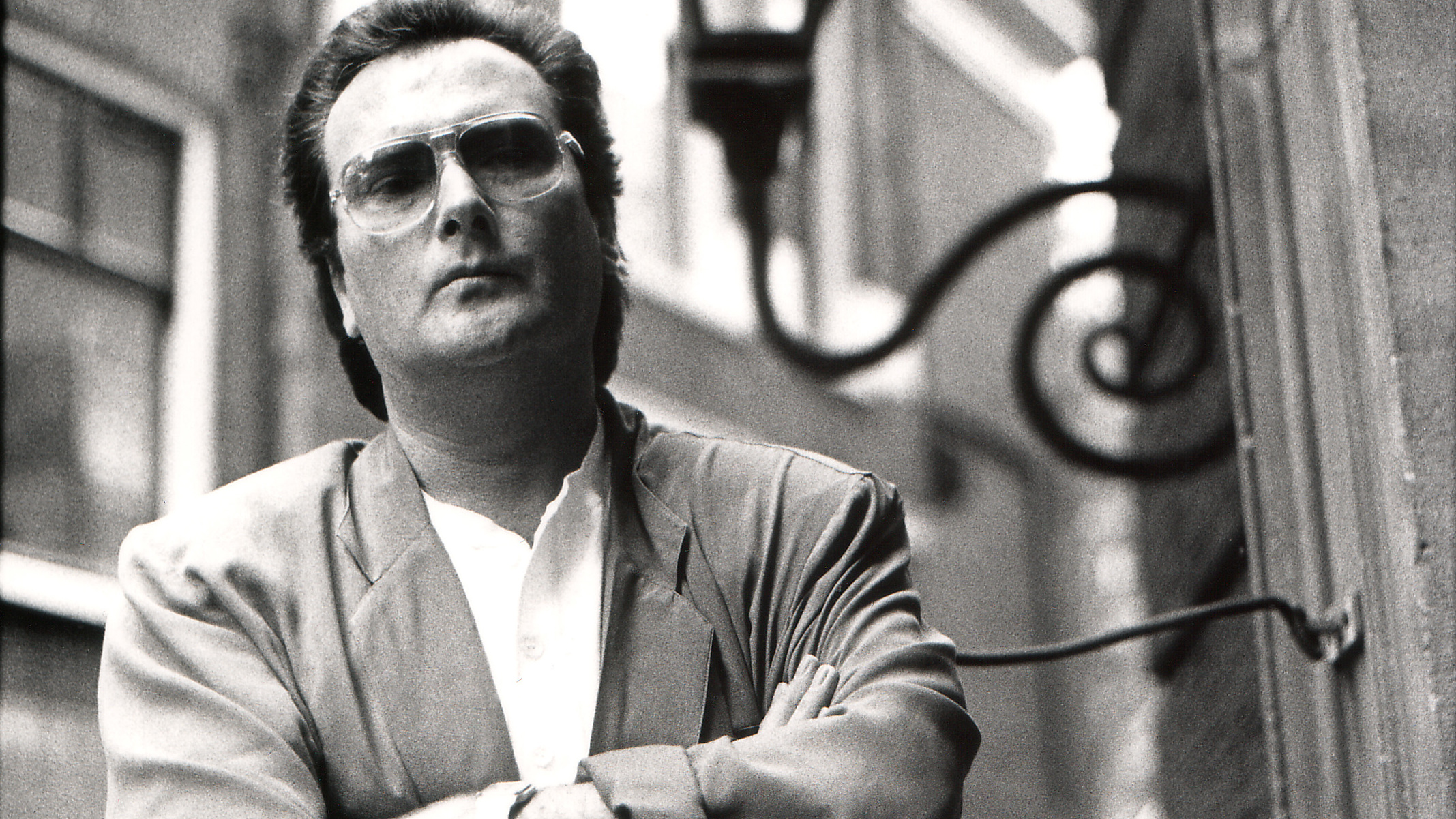

Jon Brewer – now a successful documentary maker – managed Rafferty through his most successful period before their relationship ended in acrimony.

By the late 70s, Brewer had had a hand in the early career of David Bowie, Alvin Lee and others and had a publishing company called Belfern Music. Gerry Rafferty’s promising partnership with Joe Egan as Stealers Wheel had ended after three albums and a US no.1 single in Stuck In The Middle With You.

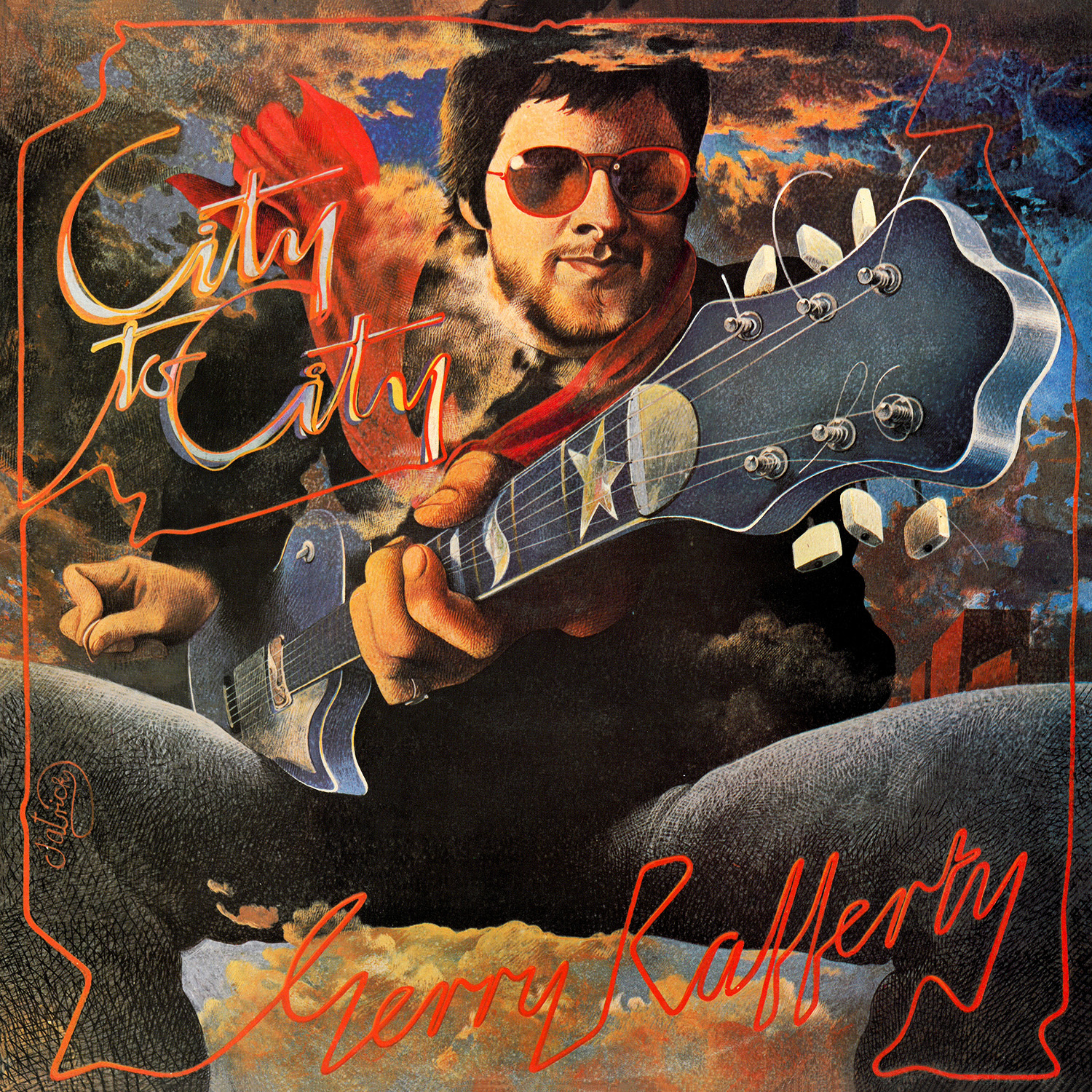

Brewer was a big fan of Stealers Wheel and met Rafferty in London. Stealers Wheel’s management company Ricochet had disappeared with the band’s money and times were tough. “His wife had just given birth to their daughter and he told me that he didn’t have any money to buy nappies,” says Brewer. “He said, ‘I’ll play you something’. And he played City To City and Baker Street – a demo without the sax part. And I went, ‘I’ll fund the album. And here’s five grand, in cash, to help you’.”

Gerry Rafferty signed up with Brewer and his production company funded the making of new album, City To City. “And that’s when the fun started,” says Brewer.

Gerry had had a tough upbringing in Glasgow and the manager sensed that he carried “tremendous resentment” about it. Not that it was all doom and gloom: “He had this great friendship with Billy Connolly [the two men were in folk duo The Humblebums] and Billy told me this amazing story. Gerry was a joker – he used to joke all the time, an absolute nutter. Him and Billy used to play a game. Do you remember how old ladies used to have those little baskets on wheels they used to push around the shops? Well, in Glasgow it was always raining and they’d go down down Sauchiehall Street on a Saturday and play this game. Gerry had a glass eye – I didn’t know this until Billy told me this story – and they’d wait until it was really pouring and they’d go out and all the old girls would put up their umbrellas. And Gerry would barge into their umbrella, shout ‘Oh my god!’, and as he hit the ground he’d take his glass eye out and let it roll on the pavement.

“Some of these old ladies used to pass out. Billy said, ‘We got 10 points if they passed out, 5 points if they screamed…’ He was a wonderful character in those days.”

When City To City was finished, Brewer shopped it around record companies. “Gerry was one of those guys that had been turned down by every record company. He had been signed to A&M. I thought the contract had finished but it turned out it hadn’t. So I had to get on to [A&M co-founder] Jerry Moss and say, ‘Look: I’ve been told that he’s never going to record for you again and I need to get him off the label. What is it going to take?’

“Jerry says, ‘Jon, I’ll tell you what we’ll do: 3, 2, 1.’

“I said, ‘What’s that?’

“He says, ‘3% on the first album, 2% on the second album and 1% on the third.’

“I went, ‘Oh, c’mon, there must be another way.’

“He said, ‘No, that’s what I want.’

“So that was the deal. I wrote to Martin Wyatt at Anchor records and they said, ‘We really want this, this record is fantastic, it’s a hit record. Let me meet Gerry.’"

Brewer's offices were just across the road. He wandered over with Gerry and left them to talk.

“Later I get a call from Martin Wyatt: ‘I wouldn’t sign that man if you gave me the record – and I know it’s a number 1 album!’ I said, ‘Why?’ He says, ‘He’s the most unbelievably obnoxious person I’ve ever met in my life.’

"‘What did he say to you?’ ‘He said that he was never going to support the album, he was never going to play in a band, and he was never going to go on the road. And that all he wanted to do was write songs for his daughter.’

"I said, ‘Right. That wasn’t a very good career move. I totally understand.’”

The same scene play out at Island records: Gerry is left alone with owner Chris Blackwell and afterwards Blackwell collars Brewer and says, “I would rather sign Gary Glitter than that man! He really can’t stand anyone in the music industry, anyone in the music publishing industry, and all he wants to do is write songs for his daughter.”

“So I go back to Gerry," says Brewer, "and say, ‘You’ve got to stop doing this – we’re going to run out of record companies!’”

Brewer took the album to the US where he got a meeting with Artie Mogull, who had then just bought United Artists with partner Jerry Rubinstein. They had Electric Light Orchestra, Kenny Rodgers, and the third artist was to become Gerry Rafferty.

When he gets there, Artie Mogull is in a hurry. He has a flight to catch.

Brewer: “He says, ‘Here’s the deal. If I have to listen to the album, I’ll give you 50 thousand. If I don’t, I’ll give you 75.’ I’m like, ‘You can’t sign an artist of mine and not listen to the record!’ He says, ‘That’s the deal’. So I took the 75.”

It worked. Months later, says Brewer, “I get this call from Artie Mogull to say, ‘Congratulations – you have a number one album in America!’ I went, ‘Are you out of your mind?’ He said, ‘No, it’s at number one.’”

Rafferty’s rise to glory hadn’t come about entirely by chance. “It was the days of payola and the days of sheds being filled with records and all sorts of things,” says Brewer. “They based chart positions on what they’d shipped, not what they’d sold. So they’d ship them, get big warehouses, put them in there.

"That’s how they regulated the charts. And as long as it was supported by radio play, who could say that it wasn’t a genuine hit? And Baker Street was an enormous radio record. It wasn’t illegal. It wasn’t, y’know, playing cricket, but that’s the way record companies worked. And they’d pay the radio stations to play the record. Boys, girls, large packets of drugs – that was payola.”

Back in England, says Brewer, he and Gerry Rafferty were becoming more and more estranged. Rafferty was “becoming obnoxious with me. He hated capitalism. He wouldn’t sit in my Rolls, he wouldn’t sit in my offices, we had to meet in these pubs and it all became very strange.

"He said to me, ‘I can’t stand the way you live, because you drive a Rolls Royce and you have this house and this and that…’ He hated the music business and everything in it.”

Things came to a head when the star told Brewer that he was planning to go on the David Frost TV show. “I said, ‘If you go on David Frost, I’m finished’. I said, ‘You’re just not the right person to do David Frost. Because one: you’re boss-eyed and you don’t want to let the fans see that, and two you really are not a people person, with all your opinions. And what’ll happen is, you’ll lose your audience.

“So he goes on David Frost, and I think it took four minutes before he’d lost his audience. He was so rude about his fanbase, about the American people and going on the road, that at the end of the day, that was it – it was all over. The next album was all organised but Gerry wanted to get rid of me."

Rafferty offered to buy himself out of his contract and Brewer turned him down. Then Capitol records made a similar offer. He turned that down too.

"They came back with a bigger offer," says Brewer, "and I said, ‘I'll tell you what we'll do. We’ll do 4-3-2.’ They said, ‘What?’ I said, 4% from the first album, 3% from the next album and 2% from the album after that…

“I won’t disclose how much I earned, but it was a substantial amount of money.”

Success, says Brewer, was the end of Rafferty. “Gerry became someone else, and it was alcohol that took him over. He died many years later in a terrible state.

“Capitol called me at one point and said, ‘We’re going to give him 5 million’. I said, ‘If you give him 5 million, you’ll never get another album’ It’s the worst thing you can do. Artists write the best songs when they’re hungry.’

"Anyway, they gave him five million and he pissed off and bought a house in the Caribbean. His next door neighbour was [Island Records owner] Chris Blackwell. How’s that for capitalism?”

Before he parted ways with Rafferty, Brewer recalls a visit from saxophone player Raphael Ravenscroft. Ravenscroft considered his contribution to Baker Street to be substantial enough to warrant a songwriting credit or a percentage of publishing money. For once, Brewer and Rafferty agreed on something – they refused to credit the sax player (demos of Baker Street show that Rafferty already had the melody of what would become the sax part, played on guitar).

Eventually, says Brewer, Ravenscroft lost his temper. “He said, ’You are not a good man! I’m going to steal something from you.’

“Now, I’d always said to my staff, ‘You must never involve yourself in a relationship with any of my artists or else I’ll be forced to fire you’. Four days later, my personal assistant suddenly disappeared. And he married her! They got married and ran off together. That’s the price I paid for being Gerry Rafferty’s manager.”

Jon Brewer is a director and producer. His most recent film, Beside Bowie – The Mick Ronson Story, is released soon on DVD. He is currently working on the official documentary on the life of Chuck Berry. Stealers Wheel – The A&M Years 3CD boxset is out now on Caroline International.