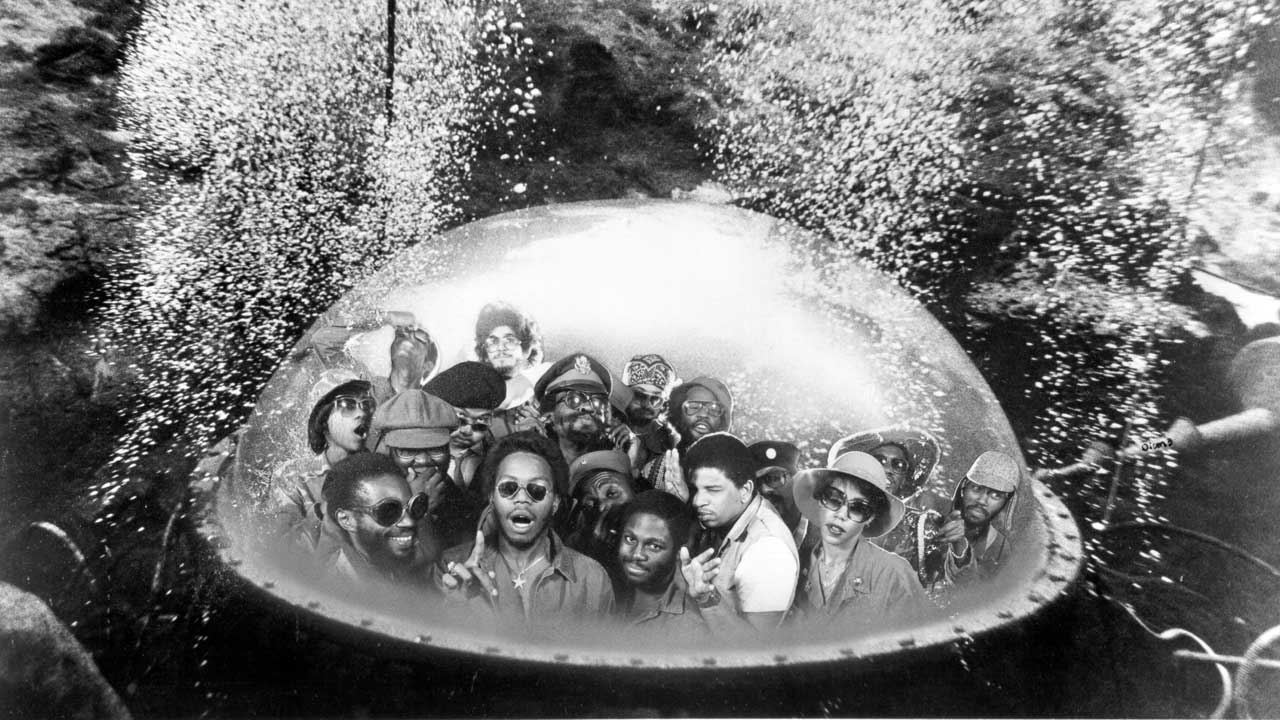

It’s late 1976, and George Clinton’s small army of singers and players, sporting a dazzling array of exotic space costumes and outsize nappies, are on stage thundering through the scorching funk-rock hybrid that recently reached an artistic peak on Parliament’s albums Mothership Connection and The Clones Of Dr Funkenstein.

Leading the action in a long blond wig, Clinton the cosmic pimp is gesticulating and testifying like a street corner preacher-turned-intergalactic ringmaster, dirtying up nursery rhymes and leading chants of “Shit, goddamn, get off your ass and jam” at the planet’s biggest party, attended by 20,000 guests of all stripes and colours.

The lights dim and Clinton disappears as the incessant groove eases down to a choral singalong ‘Swing down sweet chariot and let me ride’, stoking anticipation for the approaching big moment. Gazing upwards, singer Glenn Goins announces: “I think I hear the mothership coming. I think I see the mothership coming,” as the band stop playing and drop to their knees in genuflection as flashing lights hover over the cavernous arena, and a mini-mothership arcs from the rear of the venue.

Then, in a senses-blasting barrage of deafening noise, billowing smoke, shooting sparks and flashing lights, the gargantuan silver mothership descends on to the stage. The crowning moment is its hatch opening to reveal Clinton. Standing regally as Dr Funkenstein, he’s a vision in white with a wig, cane, huge feathered hat and floor-length ermine coat, swaggering and pimp-rolling down the steps from the craft as the band launch into the next call-and-response killer groove…

The mid-70s had seen theatrics in rock balloon into extravagant presentations that, for various reasons, often failed to transcend indulgent novelty status or achieve any desired dramatic effect: the Rolling Stones’ giant tulip-todger was poleaxed by poor sound; David Bowie’s Hunger City stood cold and imposing as its coked-up single resident; ZZ Top found themselves dwarfed by a Texas-shaped stage being dumped on by perplexed cattle.

Clinton’s Parliament-Funkadelic topped everyone by landing a colossal mothership on arena stages across the US through 1976-77’s P-Funk Earth Tour. This extra-terrestrial mardi gras became one of that decade’s biggest box-office draws and established Parliament-Funkadelic as one of the biggest bands in the US, their riotous funk-rock mutant delivering such an impact on music that its shock waves are still felt today, from rock to hip-hop.

No black band had ever been granted such a big-budget opportunity. Indeed Casablanca Records’ backing was partly enabled by the success of labelmates Kiss’s Alive! album. Clinton took it and ran as his mission to unite late-60s hard rock with soul and funk came to life like a blaxploitation film on funky Broadway, and struck a huge chord with the masses.

Clinton’s rise from struggling songwriter to galactic funk overlord began more than 50 years ago. Influenced by Jimi Hendrix’s acid-drenched virtuosity, James Brown’s primal funk, Cream’s power-riffing and Sly Stone’s multi-racial uproar, Funkadelic mixed R&B, gospel, Motown and Beatles-esque studio experimentation to forge their humping mix of high-energy rock, astral guitar solos and sweaty groove chorales, teleporting ghetto life in war-torn America to a hallucinogenic parallel world. Or as George put it, “I took all the different things and threw the shit together.”

The Mothership was a triumphant culmination of elements, individuals and experiences that started with the original Parliament relocating from New Jersey to riot-torn ’67 Detroit, a suitably anarchic war zone to blossom in. Sharing bills with the MC5 and the Stooges, they built a reputation for untamed, orgiastic live shows, further liberated by discovering LSD.

Then Funkadelic’s 1970 debut album spread its lysergic funk-rock virus into the underground water supply as they demolished racial barriers with live onslaughts and albums that, however surreal, presented role models and self-contained ideologies for beleaguered black communities. All the while they were also attracting white audiences as the craziest, hardest-rocking band on the planet.

After Funkadelic’s mind-blowing albums Free Your Mind… And Your Ass Will Follow and Maggot Brain, Clinton created 1972’s America Eats Its Young, his ambitious double-album masterpiece for which he took the production reins as the original Funkadelic splintered in drug-addled disarray. In came bassist William ‘Bootsy’ Collins and brother Phelps (‘Catfish’), who’d left James Brown after propelling milestones such as Sex Machine.

“I took that groove I got from James to Parliament-Funkadelic,” Collins recalled. “You could take that line and add fuzz, aeroplanes and stretch it! George already had the craziness going. All he needed was a serious groove. That was my contribution, bringing over that groove.

"The P-Funk was just being born then. George and me was mixing our chemistries together and it just started to work. Some of the craziest stuff happened with George. We fed off each other so much it was like a right and a left arm. It was always a natural thing. We didn’t know what we was doin’, we was just doin’ it.”

America Eats Its Young marked Clinton’s coming of age in the studio, as he moulded its complex ghetto prog.

“That album was really a test to see if I could do it straight after all that acid,” he told me. “All the ones before that I did on acid. I wanted to see if I could make any kind of sense!”

It was time to take P-Funk to the next level. Funkadelic’s Cosmic Slop (’73) was Clinton’s first stab at being radio friendly, with shorter songs. He knew he had to up his game to tap into the mainstream, so he recalled Parliament – which was last heard three years earlier on Osmium. He developed P-Funk as a code of life, even a cult, with hard-core followers calling themselves ‘maggots’, ‘clones’ or ‘funkateers’, Words previously used negatively, like ‘funky’, ‘stupid’, ‘nasty’ and ‘bad’, became hip and cool.

Still approaching P-Funk with surreal ghetto humour, Clinton was really propagating a 70s continuation of Black Power, then re-manifesting in ‘blaxploitation’ films, but weighted with enough unfettered fun and killer rock’n’roll to continue seducing white rock audiences.

He needed a new record company to make it happen. Enter old friend Neil Bogart, a key figure in the 60s bubblegum pop explosion, who enjoyed huge success with the bands Ohio Express and 1910 Fruitgum Company. He also started Casablanca Records. Bogart’s first signing was New York glam hopefuls Kiss, who struggled with early albums but gained popularity with their pyrotechnic stage show. Clinton felt Casablanca would be a good home for the expansive concepts trapezing around his brain, as they fitted in with Bogart’s raging ambition to hit mass markets.

The liaison was justified when Parliament’s first single, Up For the Down Stroke, hit the chart in June 1974, giving Casablanca their first hit – and a call-to-arms for the reborn band that included keyboard genius Bernie Worrell, Collins and mercurial guitarist Eddie Hazel, P-Funk’s carrier of the Hendrix torch. The same-titled album showed Parliament truly back in session.

Bootsy remembered these difficult times before funk was accepted by the mainstream: “‘The Funk’ was a bad word when George and myself came out with the first stuff. At one time it was illegal to say it on the air. Plus it was kind of rowdy. Any time something is that new, people tend to back off from it, and if it starts working they’ll start coming in.”

Released in April 1975, the super-funky Chocolate City was the link between re-entry and approaching orbit, starting with the title track’s hip DJ patter placing Clinton in the White House, with a star-studded administration including world-champion boxer Muhammad Ali as President. This gave rise to the next part of his visionary master plan.

“We had put black people in situations nobody ever thought they would be in, like the White House. I figured another place you wouldn’t think black people would be was outer space. I was a big fan of Star Trek, so we did a thing with a pimp sitting in a spaceship shaped like a Cadillac and these James Brown-type grooves, but with street talk and ghetto slang.”

The JB grooves coursed deeper when Collins and Catfish were joined by Brown’s trombonist Fred Wesley, sax titan Maceo Parker and trumpeter Richard ‘Kush’ Griffith. Dubbed the Horny Horns, during September 1975 they became key crew members of Clinton’s funk sweatshop at Detroit’s United Sound studios. Clinton operated around the clock, with musicians laying down rhythm tracks until they flopped at a motel across the road and another took over. The results furnished Clinton’s next few albums under different names. Poached from the Chambers Brothers, Jerome ‘Bigfoot’ Brailey was on drums throughout this period.

“I went to Detroit and started working on Mothership Connection,” he recalled. “The first day, we did Unfunky UFO, then Bootsy came up with Give Up The Funk (Tear The Roof Off The Sucker) [the first P-release to go gold]. I was in after that! We’d just go in and start a groove. I’d try to lock on and compose on the tune, instead of just playing straight through.”

“We just recorded and recorded tracks that’d end up on Parliament, Funkadelic, Bootsy or Horny Horns albums,” Bigfoot recalls. “I could see George up in the control room, laughing and putting something up his nose. But he’d hit the ‘record’ button while we were doing it, then go: ‘That’s enough.’ A month later you’d hear the track on an album with their names as writers.”

Mothership Connection, released that December, was P-Funk’s breakthrough. It was the peak that happens once in a band’s career, and the commercial package that Clinton had dreamed of (without compromising his original mission). With his singers and players at the top of their game, the album revolutionised funk, bust open black music and pointed at an inter-galactic future while embracing their heritage of Motown pop, gospel and soul.

Clinton’s initial album reference points were The Outer Limits TV sci-fi show and home-remedy radio commercials, laced with street slang imagining a parallel black universe. He liked to say the concept was vindicated by a UFO “visit” when he was driving from Toronto to Detroit with Bootsy and a bright light pinballed along the deserted street. When it hit their car, the street lights went out.

“It was like somebody out there saying they were hip to the Mothership and they approve,” Clinton reasoned. “We were nervous about the project. We had a concept that was The Bomb, but black audiences have never really bought a concept album, so we saved most of the concept for the second album (The Clones Of Dr Funkenstein) and put hits on the first to grab attention.”

Mothership Connection’s funky space odyssey begins with Clinton as space DJ Sir Lollipop hijacking the airwaves with radio station WEFUNK (“home of uncut funk… The Bomb”) before P-Funk (Wants To Get Funked Up) sets the pulsating groovescape. Mothership Connection introduces Star Child, referencing Swing Low, Sweet Chariot as a spiritual undercurrent. Clinton’s black Utopia was now the entire universe rather than one city.

The second single, the barnstorming Give Up The Funk (Tear The Roof Off The Sucker), was the album’s biggest hit, reaching No.15. Closing with Bootsy and Bernie’s Night of The Thumpasorus Peoples, the former bubbling lethally to the fore, the album became the most successful P-Funk record yet, going gold. If Parliament took trends like glam rock to their loudest extremes – Clinton’s silver platform boots boasted nine-inch heels – the album also predicted future movements such as hip-hop and its rock derivatives.

“When I first started doing this stuff it was: ‘Oh, man, he’s not singing, he’s just rapping all through the songs – and the kids are loving it! Why?! He should be singing’,” Bootsy recalled. “There was so much criticism going on. We were just: ‘Why don’t they just leave us alone and let us do the things we want to do?’ If we had’ve listened to them there would have been no P-Funk.

"George was nuts and was rebelling. I wasn’t listening to no one, I was rebelling. Sometimes it takes a certain amount of rebellion to come up with something new, cos when it’s fresh people go: ‘Nah, I can’t stand that crap.’ That’s what was happening with George and myself when we first started, really. We were delivering to the radio stations, and it was like: ‘Nah!’ [makes Dracula-movie cross gesture].

“Then the kids got into it by seeing us. They would come to the concerts and freak out. Then we started selling out concerts. That’s when the records started selling. Next thing you know, the radio had to start playing it. It was like: ‘You can’t say that on the radio,’ but we said it so much that if you didn’t say it you better get hip; ‘This is The Thang! The kids are into this!’”

The next stage in Clinton’s P-Funk invasion was launching Bootsy as a star in his own right. “I said: ‘I’m gonna have to do a record with you, Bootsy.’ At that time he was so dynamic it didn’t make sense for him just to be a Funkadelic. He had to do his own thing, because we were a psychedelic band mainly. I said: ‘We gotta get a band for you.’”

One day in the studio Bootsy, Shider and Michael Hampton were hammering a groove that seemed to start to catch fire, prompting the Bootsy to exclaim: ‘Man, we’re stretchin’ out on that one!’ Hearing this, Clinton leapt up yelling: “That’s it – stretchin’ out in a Rubber Band!” Clinton wanted Bootsy, as his first P-Funk spinoff, to widen P-Funk’s appeal to a younger audience.

“Bootsy and his group came in, and that was a whole different concept within itself,” Clinton said. “Bootsy was aimed more at kids; we called it ‘silly serious’. Parliament was a little older, and Funkadelic was a little older than that.”

According to Clinton, Bootsy needed persuading to step up front: “Bootsy didn’t want to use his nickname. I said: ‘Man, you look like a Bootsy, you got to play on it. You ain’t got to be egotistical about it, but you got to play on what’s natural.’ So we did the song We Want Bootsy. He was so embarrassed. He didn’t want to do that.”

But Bootsy’s look was all his – the star-shaped glasses, star bass and platform-boot designs, along with that cartoon wobble-Hendrix drawl. “The whole stage thing for Bootsy was my idea,” Bootsy affirmed. “George left that up to me. That’s why we got it on so good.”

Now a fabulous, enduring visual to have fun with for life, nothing Bootsy wears can be too outrageous, no platforms too tall or cape too dazzling. He also revolutionised bass playing, from the groin-level throb of Sex Machine to exploring new effects. “When he came back, he had started getting into gadgets,” recalled Gary Shider. “That put another side on it. He became the Jimi Hendrix of the bass.”

Bootsy Collins invented other characters after establishing his ultra-cool rhinestone-rock-star-from-another-planet persona, including evil twin Bootzilla and Casper The Friendly Ghost (from the TV cartoon). Clinton dubbed Bootsy’s fans ‘Funkateers’, because Bootsy was raised on the Mousekateers.

“All George needed was a spark, and that’s what I did for him,” reasoned Bootsy. “What he did for me, I probably haven’t realised it all yet.”

Along with Bootsy, Catfish and Frankie Kash, Bootsy’s Rubber Band included Fred Wesley, Maceo and classically trained keyboard player Frederick ‘Flintstone’ Allen, with P-Funk’s Mudbone and P-Nut singing on slowies. Released in January 1976, Stretchin’ Out With Bootsy’s Rubber Band is awash with the Space Bass, popping and swooping through the title track and Psychoticbumpschool.

A star was born. The group played dates with Parliament/ Funkadelic leading up to the album’s release. Fred Wesley recalled a Florida show where Bootzilla hatched in all his glory during his bass solo in I’ve Got The Munchies For Your Love: “He worked it like he was making love to the entire audience, slowly and methodically bringing himself, the bass, the band and everybody in the audience to an explosive orgasm. After that everything caught fire… Bootsy’s Rubber Band had arrived. It was, and always will be, the funkiest and most dynamic band that ever was… I just knew that we were soon to be the hottest band around."

Parliament’s follow-up to Mothership Connection had to be a stone killer, even after Clinton had used the up-front hits. Released in July 1976, The Clones Of Dr Funkenstein was lighter and more melodic. It was inevitably greeted as an anti-climax, but revealed over time as the most accessible P-Funk release of this period.

Clinton’s concept revolved around Dr Funkenstein, master technician of Clone Funk who can cure man’s ills because “the bigger the headache the bigger the pill” (the pill being himself). If archangel Starchild’s arrival was the Mothership Connection, this was his boss, whose forerunners were super-intelligent aliens who hid secrets of The Funk in the pyramids for 5,000 years. The time was right for Earth to receive them via the Clones.

After The Clones Of Dr Funkenstein became Parliament’s second Top 20 gold album, it put Clinton in a strong position with Casablanca Records (who were then enjoying the effects of Kiss taking off, and getting in early on disco by signing Donna Summer). Clinton had hatched his recent songs with the show in mind that he’d dreamed of since West Side Story opened near his old Broadway office in the late 50s.

“We’d been planning that since the Who’s Tommy and Jesus Christ Superstar," he said. "We’d been planning to do a funk opera for a long time, so when Mothership Connection and Dr Funkenstein were hit records, we put it all together.”

It was all about budget, and Bogart would foot the half a million dollars, including $275,000 for a spaceship. It was the most a record company had ever spent on a black act.

“It was our money to start off with!” Clinton boomed. “We did the big Mothership show because we paid for it ourselves. I bought the spaceship, and he paid for it with our royalties. I don’t mind, because he wouldn’t have paid us if I hadn’t bought the spaceship. This way I was able to use that spaceship on the road to promote Parliament, Funkadelic and Bootsy. It was worth more to us than money, which we probably wouldn’t have got anyway.”

Clinton was aware of the competition, and knew that even the sky couldn’t be the limit. “It was Parliament again, so if we’re gonna go back to costumes we got to go way deeper; couldn’t come back looking like Earth, Wind And Fire. We gotta come back lookin’ like we’re steppin’.”

Directed by Clinton, they employed Broadway designer Jules Fischer (who’d worked with the Stones, Bowie and Kiss), Kiss haberdasher Larry LeGaspi, an 80-strong touring party including more than 40 musicians and 35 crew, all travelling in four semi-trucks, three buses and a Winnebago camper. Dress rehearsals ran through summer 1976 in New York. The first two weeks were spent making sure the Mothership worked, along with an inflatable Rolls-Royce (which on stage would be stripped down by car thieves), a skull smoking a huge joint, and an eye-crowned pyramid.

Starting in New Orleans on October 27, the Earth Tour played to nearly a million punters around the US, cranking up again in 1977. Every night, James Jackson’s introduction included sticking a six-foot spliff into the mouth of the Funkadelic skull and lighting it with a five-foot Bic lighter as the band appeared through smoke from the pyramid. Clinton made his entrance in his pimpmobile Rolls-Royce, constructed from silver pillows on a wire frame, while the flying Bigfoot was tethered to his drum stool throughout, keeping up the planet’s essential pulse no matter what insanity raged around him.

“I got cooled off because everything landed on top of me,” he recalled. “All the foam and everything landed on the drum riser, so it was a relief! When the Mothership landed in front of me you couldn’t see me for five minutes. They would bring up the stairwell in front of me and I would complain: ‘When that thing land I can’t be seen!’ When you’re young you’re thinking: ‘How come I can’t be seen?’”

“I’ve always wanted to be in the audience when the Mothership came down,” said backing singer Dawn Silva (soon to become the Brides Of Funkenstein with Lynn Mabry). “I felt that same emotion night after night, wondering what they were experiencing. Because it was dark, all you could see was this spaceship, and I can feel the audience roaring and screaming, and couldn’t see them. Thousands and thousands of people. The vibrations would literally go right through me.”

“The audience is as much a part of the opera as we are,” Clinton said. “The entire arena is part of the event, even the parking lot attendants. When they come to the show, they can get into it from wherever they please. That’s how it’s designed.”

At one show, the pyrotechnics guy packed too much explosives, and the blasts shattered every window in the building, cutting some crowd members with broken glass. Maceo was shocked at the injured proudly “wearing their cuts like badges of honour.” He also revealed: “It’s no secret that George and a lot of the guys in Parliament used to be into some heavy stuff on a pretty regular basis, but even when they were messed up those guys could play well.”

When the tour hit New York, Clinton landed the Mothership in Times Square at daybreak – and outside the United Nations that afternoon.

“All of that, we knew it was history when we was doing it,” he beamed. “I mean, when I decide to spend half a million dollars on a show. Since we’d had to come out of the hippie vibe of the sixties and do something new, it was time to be glitter again. With the Mothership and the glitter and looking like money, I knew what we were doing. I knew that it was gonna be historic.”

Somewhat predictably, the whole glorious shebang buckled under its weight, falling victim to earthly obstacles such as hard drugs and internal squabbles. Clinton simply soldiered on, made for life after pulling off his Mothership plan, continuing to release records and taking P-Funk around the world. But his demolition of inter-musical segregation with the mighty Mothership will always be his most planet-rocking achievement.