Lemmy finds it difficult to believe that Motörhead have existed for over 30 years. “I thought we had three years in us – if we were lucky,” booms the snaggle–toothed bassist/vocalist. “You don’t think chronologically at the start, you only realise how long you’ve been around at the end.”

Motörhead – a title filched from a 1975 Hawkwind single (which Lemmy sang) – were dragged kicking and screaming into the world the same year. Lemmy had been sacked from the band after being detained at the Canadian/US border during a Hawkwind tour. The authorities had found a stash of white powder on him which they thought was cocaine (illegal in Canada) but which turned out to be amphetamine sulphate (bizarrely, still regarded then under Canadian law as a ‘pure food’). By the time he’d caught up with Hawkwind at the next gig in Toronto, however, he discovered he’d been “voted out of the band”.

After four years with Hawkwind, during which he’d supplied the lead vocal to their one and only hit, Silver Machine, in 1972, Lemmy took his dismissal badly. Very badly.

“I’d sort of seen it coming, I just didn’t know when,” he shrugs now. “The only reason they bailed me out of jail, apparently, was because my replacement couldn’t get there on time. It’s a terrible thing to be fired – especially for an offence that everyone else was guilty of. So I came home and fucked all their old ladies,” he adds. “Not the ugly ones, of course. But at least four, I took great pleasure in it. Eat that, you bastards.”

Lemmy’s earliest recollections of Motörhead, the band, involve, “Incredible poverty, living in squats. This bird we knew called Aeroplane Gaye used to work under a furniture store in Chelsea, and if anyone quit early we’d all dash down there and rehearse. We were that broke, but we did alright. We were struggling for a long time with no bread, then over about six months it just went whammo.”

The prototype Motörhead included former Pink Fairies guitarist/vocalist Larry Wallis and drummer Lucas Fox. Although they supported Greenslade at London’s Roundhouse on July 20, 1975, this line-up proved short-lived, and the latter was eventually replaced, in late 75, by Phil ‘Philthy Animal’ Taylor. “I met Lemmy through speed really,” Taylor later claimed. “Y’know, dealing and scoring. I wasn’t actually playing in a band at the time.”

After Motörhead had cut their debut On Parole album for United Artists, the company rejected it (the album remained in the vaults until the band finally hit the charts with Bomber). The following March, Taylor found himself among a group of blokes trying to earn a few extra quid by painting a houseboat in Battersea. One of them was former Curtis Knight/Blue Goose guitarist ‘Fast’ Eddie Clarke, who was interested to learn that Taylor’s group were considering adding a rhythm player.

“So we organised an audition and jammed all afternoon, and Lemmy and I found we had a lot of things like The Yardbirds in common,” recalls Clarke now. “But Larry didn’t show up ’til the end, and when he did he wasn’t in very good humour.

“I didn’t hear anything for ages and assumed Larry didn’t want me in the band, then one Saturday afternoon there was a knock on the door and Lemmy was standing there. He gave me this fucking bullet belt and leather jacket and said, ‘You’re in’. Larry had gone and I had my uniform!”

After we got Eddie and Phil in I knew we had something special,” Lemmy muses. “That was an excellent band from day one. I’d only written three songs for Hawkwind, and I wasn’t too good at it yet. But this band has always been the eternal underdog, and we’re good at it.”

“It wasn’t until after three or four auditions that I realised we didn’t sound normal,” says Clarke. “Obviously, drink and speed were important in shaping the band,” he continues. “I was a dopehead. Speed was something that they all did, and I soon found myself doing it as well.”

Motörhead’s break came in typically freak-ish fashion when Gerry Bron, the boss of Bronze Records, agreed, as a favour to a booking agent friend, to issue what became the first ever Motörhead single: their cover of cult 60s classic, Louie Louie.

Bronze Records had told the band that if Louie Louie went Top 75, they could secure them a place on Top Of The Pops. Sure enough, the band recorded their slot for the show on the Wednesday, and Clarke, who was “doing a painting job” on the following night, “had to ask the punters if we could watch their telly, because I was on in a minute! I was standing there in my overalls with a paintbrush in my hand…”

The success of Louie… was the start of a love/hate relationship that would benefit both band and label, yet culminate in trench warfare.

“We always seemed to have a problem with Motörhead,” Gerry Bron recalls with a sigh. “Nobody liked them, not on a professional level. They had a fantastic following, but licensees around the world absolutely hated them. We had a terrible job getting them to work with the band.”

“Yeah, Gerry Bron signed us as a favour, but he went on to release five of our albums, so that’s one helluva favour,” says Lemmy defiantly. “So, again, fuck you!”

The relationship between band and label became so fractious that Lemmy would often tell audiences to go out and steal the group’s latest recording, “Because we don’t get the fucking royalties anyway.”

Early on, as a gesture of solidarity, Motörhead decided to split the profits equally three ways, even though Lemmy was writing the lyrics and Eddie the majority of the riffs. “We knew if we did make it that we didn’t want Lemmy and I coming to work in Rolls Royces and Phil on a pushbike,” says Clarke. As the guitarist now insists, the reason for the band’s early success was their very togetherness. Although there was tension, their bond was seemingly unbreakable. “You hear a lot of good things and a lot of bad things about Lemmy, and most of them are true,” said Taylor at the time. “He is a cunt, he is a bastard, he does knock other people’s chicks off. But he’s also incredibly funny. Every time you go out with him it’s a memorable experience.”

“We had a bond, and it went beyond whether you liked someone or not,” adds Clarke now. “We felt almost indestructible, because we’d had so much shit thrown at us and we’d decided that no matter what happened, we were gonna fuckin’ carry on.”

Motörhead’s now infamous hedonism even began to reach the dailies when on December 2, 1980 the Daily Mirror reported that a suitably refreshed Taylor had broken his neck after falling down a flight of stairs in a Belfast hotel. Thankfully, only vertebrae were fractured. Were there ever any concerns that somebody might actually die of the lifestyle, though?

Clarke: “Not for a fucking minute. We were too busy partying. There were times when I got the red mist and let off a bit of steam, or Phil would smash up the odd hotel room and break his hand, but that was all part of it. The fights between me and Phil were legendary, we’d really try to hurt each other.”

“I was worried about the band many times,” admits the band’s first manager, Doug Smith. “I once thought Phil Taylor was dead of an overdose in New York. And in America the police arrive whenever you call an ambulance, so I’d been going around his room hiding every drug I could find, hoping they’d think he’d just collapsed. It was life-threatening all the time, for all of them – even Lemmy, who I once thought was gonna have a heart attack when we got to a gig in Canada and there was no speed around.”

In late 79, Motörhead made London’s Evening News for ‘clocking in a staggering 119 decibels at a recent concert’. An unrepentant ‘band leader Lemmie’ (sic) retorted: ‘The kids may be injuring themselves, but how could we stop them from pressing their heads against the speakers? They keep on shouting to turn it up’. The Daily Mirror then joined in, declaring: ‘Their music is so loud it’s like your brains being forced down your nose.’

The release of the Overkill and Bomber albums both came in 1979, but they’d had plenty of time in which to perfect their sound. The latter crashed into the charts at No.12, causing Sounds to describe it as ‘music to perform lobomoties to’. To promote it, they had already sold out two nights at London’s prestigious Hammersmith Odeon.

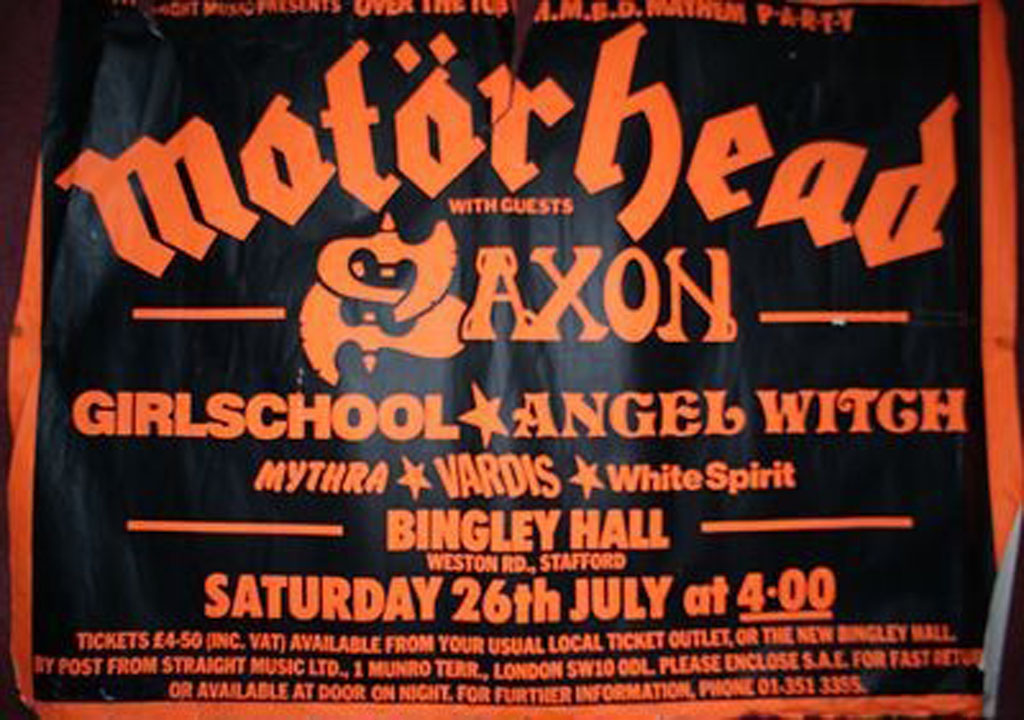

On July 26, 1980, the band played a show that crowned their early achievements. The Heavy Metal Barndance (also know as The Headbangers’ Ball) at Stafford Bingley Hall also featured Saxon, Girlschool, Angel Witch, Mythra, Vardis and White Spirit, and was rightly hailed as a success. But even then, the strain was beginning to show.

“Lemmy had been up for three days, drinking vodka and fucking chicks,” Clarke explained years later. “We’ve got 12,000 kids crammed in and waiting for us. All day people have been offering me lines of coke and everything, and I’ve had one fucking Heineken because I want to be together for this show. 55 minutes into the set, Lemmy disappears backwards and collapses. Afterwards, me and Phil are furious, going: ‘You let us down’. And he was saying, ‘Me being up for three nights had nothing to do with it’. The fact that he was up for three days getting blow-jobs had nothing to do with the fact that he’d collapsed onstage? No, of course not!”

Although 1980’s Ace Of Spades entered the chart at No.4, Clarke remembers it as “becoming a little more difficult. There was pressure because we were famous.” Yet Lemmy’s prime recollections are that the band were “ready to kill”. Again, Sounds went overboard giving …Spades five stars and insisting: ‘Motörhead are heavy metal in the only meaningful sense of the term. Everyone else is just pretending’.

The band’s pinnacle came in 1981 when live album No Sleep ’Til Hammersmith entered the UK album charts at No.1. The bassist was in New York at the time and remembers being asleep when he received the news, and although he claims to have told whoever had made the call to ring him back the next morning, he regarded the chart placing as a vindication. Clarke’s biggest regret was that with being in the US, nobody could buy them any celebratory drinks.

“The strangest thing though,” he says now, “was that it got an over-the-top review in Melody Maker, who were the people who’d called us the worst band in the world. I said to Phil, ‘Now suddenly we’re the definitive live band, they were calling us cunts last week’.”

“We knew that No Sleep… was gonna do well because people had been waiting for a live album from us for three years, but never in our wildest dreams did we think it would go straight in at No.1,” Lemmy confesses, and admits that at first the band didn’t even want it released at all. “It was also our death knell because you can never follow a live album that goes in at No.1. What are you gonna do, put out another one?”

Just before the band had departed for their second US tour to promote the then new Iron Fist album, a series of dawn raids on their homes had led to the arrest of Philthy for possessing 2.2 grams of cannabis. Fortunately for Lemmy and Fast Eddie, they’d stayed out all night, but that didn’t stop them from claiming in Sounds that somebody was “out to stitch us up”.

While the band were away, police were also called to Lemmy’s gaff after his flatmate, actor Andrew Elsmore, was found stabbed six times in the head and chest with his body partly burned.

As Clarke now explains, things had started to become strained between himself and the other two. After the murder at Lemmy’s pad, Doug Smith had moved the group into a shared house in Clapham. While the tour continued, Clarke’s then girlfriend was the first to move in, also picking the best bedroom.

“I know it sounds incredibly petty, but it was the beginning of the end,” sighs Clarke now. “I was also seeing one of Lemmy’s ex-girlfriends, and even though I asked him if it was alright, he never got over it. Lemmy forgot the golden rule, he started to think about whether he liked me or not.”

The disappointing reaction to the Iron Fist album and tour made it clear that the magic wouldn’t last forever. Bronze had failed to get the album into the shops in time for the tour.

“The Iron Fist album was bad, inferior to anything else we’ve ever done,” agrees Lemmy now. “There are at least three songs on there that were completely unfinished. But there you go, we were arrogant. When you’re successful that’s what you become, you think it’ll go on forever.”

After seven years of threatening to do so, Eddie Clarke finally quit the band in May 82 after a blazing row in a New York hotel room. Taylor followed suit two years later (although he would return for a brief period). Motörhead, however, continue to roll on…

**This feature was first published in _Classic Rock Special No.4: Motörhead**_