When it comes to music, Opeth’s Mikael Åkerfeldt is a bit of an anorak. The snow-peaked, malevolent beauty of Opeth’s immaculately sculpted new album, Ghost Reveries, makes that fact clear. But it’s talking at length with the guitarist, vocalist and songwriter (and, he admits, Classic Rock subscriber) that reinforces his passion.

“I still sometimes work at my local Gothenburg record store,” he says at one point. “It’s not that I need the money, but I like recommending great music to customers. Things like Van Der Graaf Generator’s Pawn Hearts; twisted and dark stuff, with a disharmonic feel.”

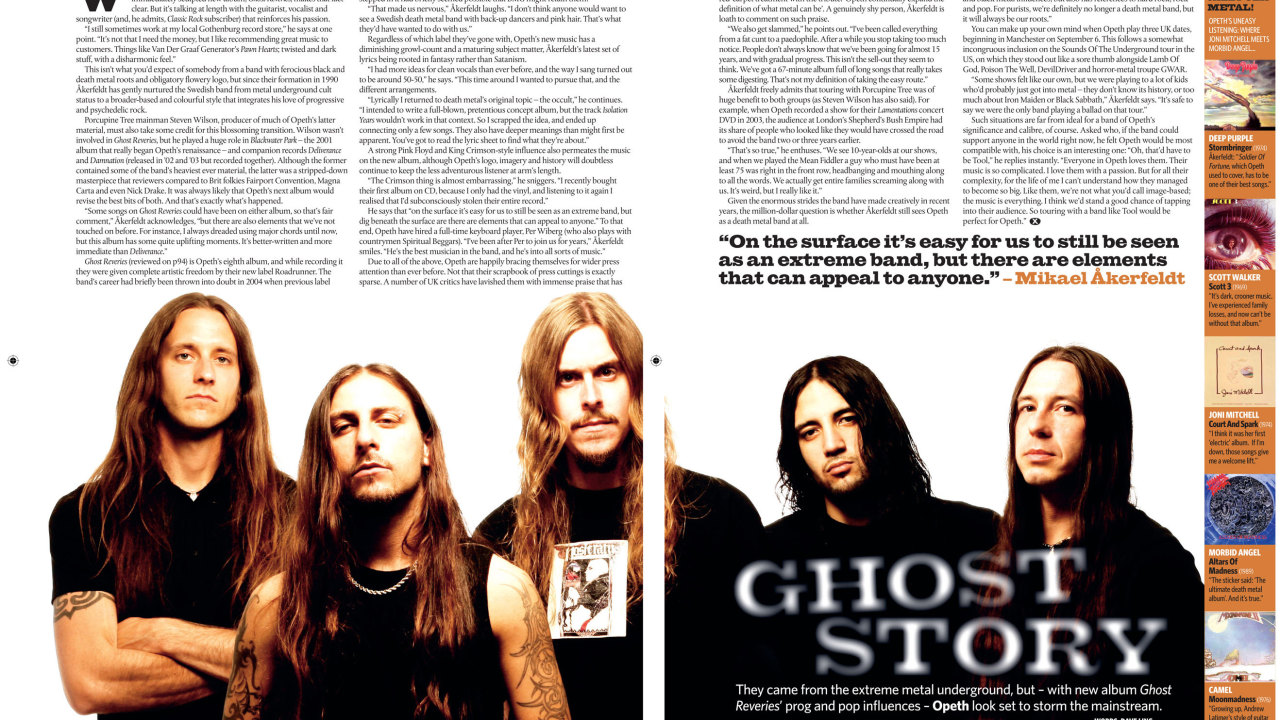

This isn’t what you’d expect of somebody from a band with ferocious black and death metal roots and obligatory flowery logo, but since their formation in 1990 Åkerfeldt has gently nurtured the Swedish band from metal underground cult status to a broader-based and colourful style that integrates his love of progressive and psychedelic rock.

Porcupine Tree mainman Steven Wilson, producer of much of Opeth’s latter material, must also take some credit for this blossoming transition. Wilson wasn’t involved in Ghost Reveries, but he played a huge role in Blackwater Park – the 2001 album that really began Opeth’s renaissance – and companion records Deliverance and Damnation (released in 02 and 03, respectively, but recorded together). Although the former contained some of the band’s heaviest ever material, the latter was a stripped-down masterpiece that reviewers compared to Brit folkies Fairport Convention, Magna Carta and even Nick Drake. It was always likely that Opeth’s next album would revise the best bits of both. And that’s exactly what’s happened.

“Some songs on Ghost Reveries could have been on either album, so that’s fair comment,” Åkerfeldt acknowledges, “but there are also elements that we’ve not touched on before. For instance, I always dreaded using major chords until now, but this album has some quite uplifting moments. It’s better-written and more immediate than Deliverance.”

Ghost Reveries is Opeth’s eighth album, and while recording it they were given complete artistic freedom by their new label Roadrunner. The band’s career had briefly been thrown into doubt in 2004 when previous label Music For Nations was bought and subsequently wound down by BMG. There were no less than 31 offers for the band’s signatures,, and before Roadrunner stepped in it had briefly seemed possible that BMG might retain them.

“That made us nervous,” Åkerfeldt laughs. “I don’t think anyone would want to see a Swedish death metal band with back-up dancers and pink hair. That’s what they’d have wanted to do with us.”

Regardless of which label they’ve gone with, Opeth’s new music has a diminishing growl-count and a maturing subject matter, Åkerfeldt’s latest set of lyrics being rooted in fantasy rather than Satanism.

“I had more ideas for clean vocals than ever before, and the way I sang turned out to be around 50-50,” he says. “This time around I wanted to pursue that, and the different arrangements.

“Lyrically I returned to death metal’s original topic – the occult,” he continues. “I intended to write a full-blown, pretentious concept album, but the track Isolation Years wouldn’t work in that context. So I scrapped the idea, and ended up connecting only a few songs. They also have deeper meanings than might first be apparent. You’ve got to read the lyric sheet to find what they’re about.”

A strong Pink Floyd and King Crimson-style influence also permeates the music on the new album, although Opeth’s logo, imagery and history will doubtless continue to keep the less adventurous listener at arm’s length.

“The Crimson thing is almost embarrassing,” he sniggers. “I recently bought their first album on CD, because I only had the vinyl, and listening to it again I realised that I’d subconsciously stolen their entire record.”

He says that “on the surface it’s easy for us to still be seen as an extreme band, but dig beneath the surface are there are elements that can appeal to anyone.” To that end, Opeth have hired a full-time keyboard player, Per Wiberg (who also plays with countrymen Spiritual Beggars).

“I’ve been after Per to join us for years,” Åkerfeldt smiles. “He’s the best musician in the band, and he’s into all sorts of music.”

Due to all of the above, Opeth are happily bracing themselves for wider press attention than ever before. Not that their scrapbook of press cuttings is exactly sparse. A number of UK critics have lavished them with immense praise that has included them being called ‘probably the best band in the world’ and ‘the most unique band on the planet’, while Rolling Stone gave them the red-carpet treatment with the tribute: ‘Opeth continually expand the definition of what metal can be’. A genuinely shy person, Åkerfeldt is loath to comment on such praise.

“We also get slammed,” he points out. “I’ve been called everything from a fat cunt to a paedophile. After a while you stop taking too much notice. People don’t always know that we’ve been going for almost 15 years, and with gradual progress. This isn’t the sell-out they seem to think. We’ve got a 67-minute album full of long songs that really takes some digesting. That’s not my definition of taking the easy route.”

Åkerfeldt freely admits that touring with Porcupine Tree was of huge benefit to both groups (as Steven Wilson has also said). For example, when Opeth recorded a show for their Lamentations concert DVD in 2003, the audience at London’s Shepherd’s Bush Empire had its share of people who looked like they would have crossed the road to avoid the band two or three years earlier.

“That’s so true,” he enthuses. “We see 10-year-olds at our shows, and when we played the Mean Fiddler a guy who must have been at least 75 was right in the front row, headbanging and mouthing along to all the words. We actually get entire families screaming along with us. It’s weird, but I really like it.”

Given the enormous strides the band have made creatively in recent years, the million-dollar question is whether Åkerfeldt still sees Opeth as a death metal band at all.

“The new album makes that harder than ever to answer,” he says, while still pondering the question. “Our music still has many death and black metal influences, but also has references to hard rock, rock and pop. For purists, we’re definitely no longer a death metal band, but it will always be our roots.”

At he time this was written, Opeth were about to play three UK dates, beginning in Manchester on September 6. This followed a somewhat incongruous inclusion on the Sounds Of The Underground tour in the US, on which they stood out like a sore thumb alongside Lamb Of God, Poison The Well, DevilDriver and horror metal troupe GWAR.

“Some shows felt like our own, but we were playing to a lot of kids who’d probably just got into metal – they don’t know its history, or too much about Iron Maiden or Black Sabbath,” Åkerfeldt says. “It’s safe to say we were the only band playing a ballad on that tour.”

Such situations are far from ideal for a band of Opeth’s significance and calibre, of course. Asked who, if the band could support anyone in the world right now, he felt Opeth would be most compatible with, his choice is an interesting one:

“Oh, that’d have to be Tool,” he replies instantly. “Everyone in Opeth loves them. Their music is so complicated. I love them with a passion. But for all their complexity, for the life of me I can’t understand how they managed to become so big. Like them, we’re not what you’d call image-based; the music is everything. I think we’d stand a good chance of tapping into their audience. So touring with a band like Tool would be perfect for Opeth.”