The phenomenal success of Pearl Jam's first two albums made the Seattle quintet one of the biggest bands on the planet, but as the decade unfolded, the group's reluctance to play the music industry game had severely affected their standing and popularity.

Having announced their arrival in the summer of 1991 with Ten, then set a new record, in October 1993, for the largest first week sales of any album with its wired follow-up Vs., a record it held for five years, it seemed that the only thing that could stop Pearl Jam’s momentum was Pearl Jam themselves. Which was exactly what happened.

As frontman Eddie Vedder wrestled creative control away from his bandmates, both 1994’s Vitalogy and 1996’s No Code eschewed the huge alt-rock anthems that made the band's name, and instead were filled with odd, experimental art and garage rock tracks with few obvious singles. Both albums, it should be noted, debuted atop the Billboard 200, but Pearl Jam were clearly way too pissed off by the industry machine to care. They refused to make promotional videos for the singles they did release, refused to be photographed for album artwork, and spent countless hours on their exhausting and highly involved legal battle with Ticketmaster: trying to circumvent venues which worked with the ticketing agency resulted in an off-piste, bizarre and challenging touring schedule which only exacerbated internal and external tensions.

When they picked up their Grammy for Best Hard Rock Performance for Spin The Black Circle in 1996, the band appeared bored, bemused and disinterested: "Thanks, I guess," said Vedder, after suggesting that the accolade might have been appreciated by his late father. Within the ranks there were also problems with alcohol and drug use, mounting personal grievances and endless rumours that they were on the verge of splitting.

And if Pearl Jam were retreating from the spotlight at a rate of knots, a sizeable chunk of their fanbase was checking out too, confused, irritated and disappointed. No one could accuse Pearl Jam of making music that was bad, phoned in or disinteresting, but many fans had lost patience and interest. Some weren’t even aware that the group so regularly on MTV in the early '90s were making and releasing music at all.

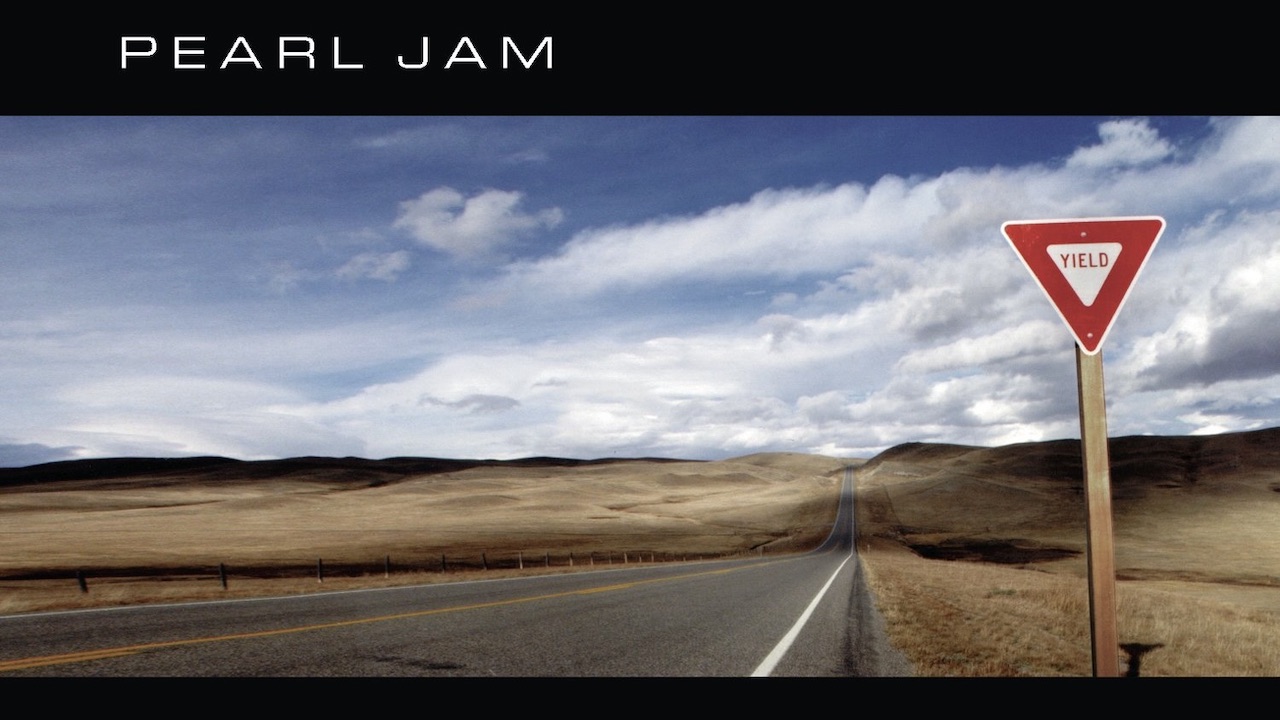

In 1997, Pearl Jam found themselves at a crossroads; should they continue down this road and see their appeal dwindle even further until they inevitably ended up nothing more than a cult band who had a brief moment in the sun? Or would they ease up on their stance against the industry, allow an obviously-stressed Vedder to release the reins a bit, and return to making the kind of wonderfully massive songs that made everyone fall in love with them?

Luckily for them, and happily for us, with Yield, they choose the latter option.

Towards the end of the recording sessions for No Code, Eddie Vedder remarked to bassist Jeff Ament that maybe the other members should contribute more to the album, as he was struggling with the workload.

Ament relayed the conversation to MTV just prior to the album’s release, saying “I think the last couple records, Eddie has really been at the helm of those records. I remember at the end of the last record, he said, 'Y'know, this was really a lot of work for me, and next time, it would be great if I didn't have to work so hard on the arrangements, and if people came in with more complete ideas, and even more complete songs, that would really help me out a lot,'. And I think everybody took that to heart.”

This liberating sea change brought with it a new sense of openness, optimism and opportunity for Vedder's bandmates, guitarist Mike McCready summing up the new frame of mind when he told Guitar World, "I used to be afraid of him and not want to confront him on things ... We talk more now, and hang out ... He seems very, very centered now.”

Vedder may also have been aware of the sheer volume of material that had been released by members of Pearl Jam outside of the unit over the last couple of years. Seattle supergroup Mad Season, co-founded by a post-rehab McCready, released their album Above in 1995, Ament’s Three Fish side project released their self-titled debut in 1996, and guitarist Stone Gossard's second band, Brad, released Interiors, their second album in 1997. Clearly this was a group of musicians and songwriters with material, and often very, very fine material, to contribute. Vedder acknowledged as much when he told MTV, "Stone was writing music and lyrics. Jeff had music and lyrics. I had music and lyrics... we were able to team up, y'know. Have a partnership there and team up and write together on this one.”

The result was that, unlike the rather one-sided credit list on Vitalogy and No Code, on Yield, Vedder is credited as the sole writer of only two tracks, Wishlist and MFC. This in turn led to a far more rounded sounding album, and a happier camp overall.

“I think the fact that everybody had so much input into the record, like everybody really got a little bit of their say on the record, and I think because of that, everybody feels like they're an integral part of the band." Ament told MTV.

The first listen to this new, more unified Pearl Jam the public had was the album’s first single Given to Fly. Released on December 22, 1997, it represented something of a return to the classic anthemic stadium rock of the band’s earliest years, with McCready’s Zeppelin-esque riffs sublimely coalescing with Vedder’s gritty, soaring vocal.

It was well received, even if a few commentators did suggest the similarities between Led Zep’s Going to California were a little too close to full blown plagiarism, something McCready himself shrugged off when he admitted to Massive Magazine, "It's probably some sort of rip off of it I'm sure...Whether it's conscious or unconscious but that was definitely one of the songs I was listening to for sure. Zeppelin was definitely an influence on that.” Whatever, Given to Fly piqued the interest of those who were starting to lose interest in the band.

Yield followed on February 3, 1998. It entered the Billboard 200 at number 2, the first Pearl Jam album not to top the chart since debut album Ten. In the UK, it peaked at number 7, again their lowest placing since Ten. Those chart placings, whilst not disastrous by any means, could be cited as evidence of the band’s slide in popularity, but as more people began to hear the album it maintained momentum and eventually comfortably outsold No Code.

Press reviews were certainly the most positive they had been in a while, with Metal Hammer’s Dan Silver, in his 8/10 review, brilliantly summing its appeal in noting, “Like guru Neil Young, it’s clear that Pearl Jam are determined to follow their own bent when it comes to putting out records. The upshot of this is that not every shot is going to hit the target. Thankfully Yield is considerably more hit than miss, like No Code minus the new age weirdness or Vitalogy with the songs.”

Twenty-five years on, with all of that context a mere spec in the rear-view mirror of Pearl Jam’s career, Yield just sounds like another fantastic album from one of the 90’s very best bands.

Opener Brain of J is one of the best out and out rockers that PJ have ever penned, while the aforementioned Given to Fly, second single Wishlist and Low Light are beautiful, soaring, euphoric, life affirming epics, that have gone on to become firm fan favourites. It also features songs such as In Hiding and Faithful that are less heralded, but absolute gems in the band's stellar catalogue. The weird, experimental Vedder-isms, such as the clanging Red Bar, are kept to a bare minimum.

But, for all its immense quality, Yield is dominated by Do The Evolution, Vedder’s favourite song on the album. "I can listen to like it's some band that just came out of nowhere," he told MTV. "I just like the song. I was able to listen to it as an outside observer and just really play it over and over. Maybe because I was singing it from a third person so it didn't really feel like me singing."

Despite never being released as a physical single, the song became a huge hit, a fact not unconnected to it being the rawest, most raucous and rollicking that Pearl Jam had sounded for years. Plus - surprise! - it came with an iconic video. Six years since the 1992 video for Oceans, Pearl Jam decided to return to making promotional video. Although the band members still wouldn’t appear in the video themselves, it was another sign that their hard-line refusal to play the game was thawing somewhat.

Co-directed by Spawn creator Todd McFarlane, who also worked on Korn’s award-winning Freak on a Leash video, the promo serves as an animated history of our planet, with dinosaurs being wiped out, the evolution of man, the building of the pyramids, fall of the Roman Empire, fascistic rallies, stock brokers mass suicides and nuclear bombs obliterating entire cities in a mere four minutes. It wasn’t much fun, but it is a dizzying watch, and an incredibly powerful statement.

It quickly became evident that the revitalised Pearl Jam had emphatically recaptured the imagination of a wavering fan base. When the band announced a tour of Australia, it sold out within 17 minutes of going on sale, an indication that those that were on the fence in recent years had been seduced anew by this more inviting and instantaneous set of songs.

What's more, Pearl Jam have never looked back since. Yield might not be considered a classic album to stand alongside Ten and Vs. are, but it may well be just as important as those seminal releases, for giving Pearl Jam a sense of unity, freedom, confidence and hunger they've maintained along a rather smoother path to becoming one of the biggest rock bands of their generation.