I dug the Eagles from the day I first heard Take It Easy as a 12-year-old schoolboy, the song transporting me from South London to an imagined California in just a few mellow minutes. I’m aware I should loathe them for all the reasons the London/New York/Detroit rock-critic cabal reviled them back in the day: for their arrogance and self-satisfaction, their apolitical hedonism, the wanton detachment from reality they shared with the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin and other stadium behemoths.

“They’re about as exciting as watching paint dry,” sneered their Asylum label-mate Tom Waits, biting the hand that fed him after they put cash in his coffers by covering his song Ol’ 55. (Later, rather more grown-up and grateful, he apologised to Don Henley.)

I should also despise the Eagles for smoothing down the torn-and-frayed country soul of Gram Parsons, whom they never properly acknowledged as a primary influence, and for estranging founder member Bernie Leadon and then bolting on their very own Ronnie Wood – Midwestern jester Joe Walsh – in Leadon’s place. And yet I confess I love the Eagles’ clean country-rock pop and their heavenly group harmonies. I love the gliding sweetness of Peaceful Easy Feeling, the soaring choruses of Already Gone, the sultry funk of On The Border, the pining pathos of Hollywood Waltz, the Spanish-tinged country-pop perfection of New Kid In Town. Oh, and Hotel California wasn’t a bad song either.

I even admire the way the Eagles nixed their relationship with Brit producer-to-the-gods Glyn Johns, beefed up their sound with the help of producer Bill Szymczyk – who’d helmed hit albums by the James Gang and by that Midwestern band’s departed star Walsh – and became a bona fide rock band.

Glenn Lewis Frey, who died on January 18, had much to do with said beefing-up. “Already Gone, that’s me being happier,” he said of the Poco-on-steroids track that opens the Eagles’ 1974 album On The Border. “That’s me being free.”

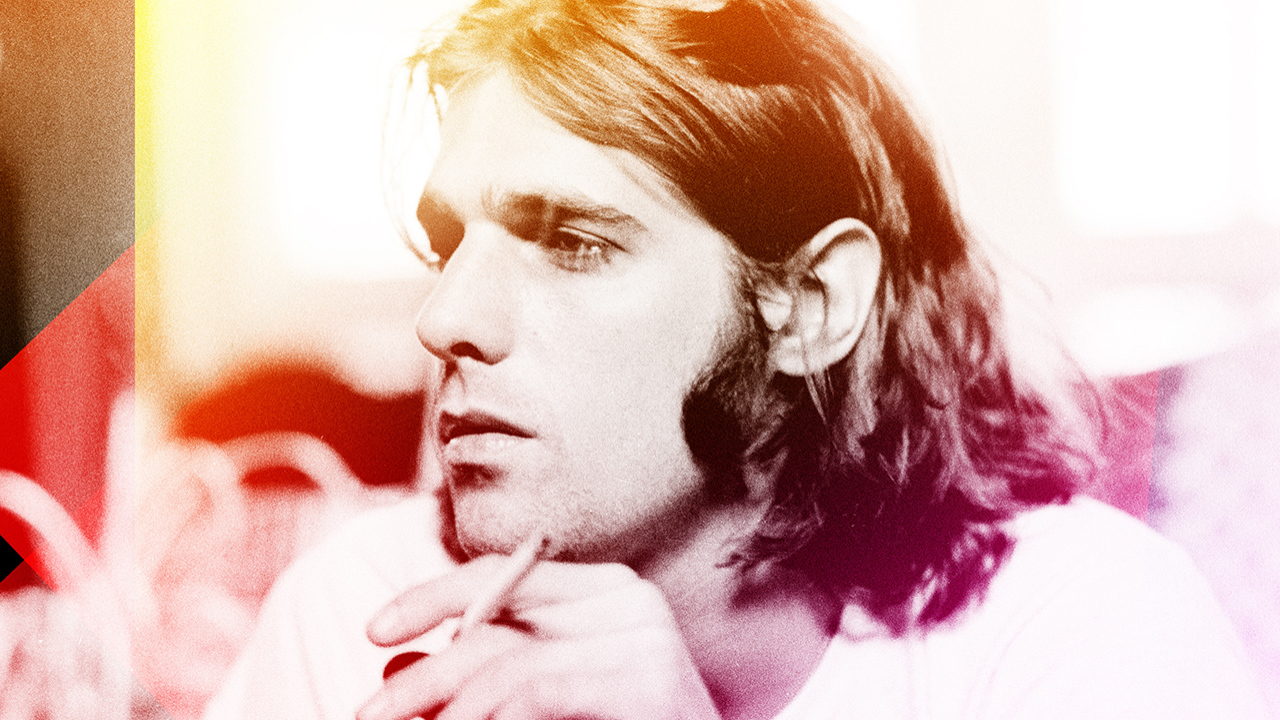

It was Frey who fronted and drove the band that rose from being skinny wastrels at West Hollywood’s fabled Troubadour club to being superstars who championed the fast-lane life and sold out America’s vast stadiums. “In the beginning, Glenn had very long hair and would always come sidling up and coming on to you,” remembered local scenester-photographer Nurit Wilde. “But he didn’t talk very much about what he was doing. He seemed to be kind of poor, a guy with no money and no prospects, and yet he was always at the Troub.”

Born in Detroit on November 6, 1948, Frey took the urban grit of his hometown – where he played in local garage bands such as the Mushrooms and backed the scene’s greatest white hope Bob Seger on 1968’s Top 20 hit Ramblin’ Gamblin’ Man – and injected it into the balmy Canyon milieu of laid-back Los Angeles. “Glenn adds the grease,” Don Henley told Crawdaddy! in July 1974. “He’s all action and he moves more than any of us trying to get people off. [He’s] got a real positive ego and he’s not afraid to do things, even though sometimes he does them wrong. He pulls us all through because he’s the catalyst.” Manager Irving Azoff would later refer to Frey as the Eagles’ “quarterback”.

Frey was a proper rock star, a pseudo-desperado with lissome Californian blondes dangling off every limb. After moving to LA in early 1969 and pairing up with Texan import JD Souther to form country-rock duo Longbranch Pennywhistle, Frey took their pal Jackson Browne’s song Take It Easy and turned it into an anthem of footloose post-hippie hedonism. ‘Lighten up while you still can,’ he breezily counselled on what turned out to be the Eagles’ first single in May 1972. ‘Don’t even try to understand.’ He’d met his new bandmates – drummer/singer Henley, bassist/singer Randy Meisner, guitarist/banjoist/singer Bernie Leadon – in the same place he met everyone else on the scene: the Troubadour.

If Henley was the subtler presence within the group – and blessed, moreover, with the creamy tenor that was the Eagles’ real signature sound – Frey it was who embodied the outlaw swagger of 70s LA, singing the lead vocal not just on Take It Easy but on Peaceful Easy Feeling, and later on Tequila Sunrise, Already Gone, Lyin’ Eyes, New Kid In Town and Heartache Tonight. As with so many great creative partnerships – from Lennon and McCartney to Stills and Young – Henley without Frey would never have wound up in the biggest American rock band of the decade.

For the rest of America, the Eagles became the prism through which the fantasy of Southern California was now filtered. Just as Frey himself had dreamed of the Pacific Ocean and the Sunset Strip as he listened to Beach Boys and Buffalo Springfield records back in Michigan, so now America hungered for Los Angeles as it devoured One Of These Nights, Best Of My Love and the epic meta-statement that was Hotel California.

“It was the scene that attracted them,” remembered Ron Stone, who worked for David Geffen and Elliot Roberts when the Eagles were first signed to Asylum. “The sound may have originated in Michigan or Texas, but it was brought to Southern California and then identified as the sound from Southern California. Because that’s where this particular music was being prized.”

“My feeling,” Frey told Phonograph Record’s Tom Nolan in June 1975, “is that Los Angeles is the Rome of North America, during the chaos. And if there’s gonna be any kind of fall of the dynasty, I’d like to see it from LA, ’cause I think LA will feel it first.” But he also added that “the nights after it rains, LA is the most beautiful city in the world… the sun goes down, you’re up on Mulholland, all of a sudden you see this incredible light show – it’s just a turn-on”.

“The weird thing about the Eagles was that none of them was from California,” said fellow LA musician Chris Darrow, formerly of Kaleidoscope. “And most of the California guys resented that, because the world looked at the Eagles as the essence of California.” Not Neil Young, however. “If only for perfectly capturing the feel of LA,” he said in 1975, “the Eagles are the one band that’s carried on the spirit of the Buffalo Springfield.”

How did Frey and Henley succeed where their stylistic forebears (Poco, Parsons, Darrow et al) did not? For two reasons. First, because it never occurred to Poco – or to the Flying Burrito Brothers or the Fantastic Expedition Of Dillard & Clark – that Californian country rock could be packaged as efficiently and commercially as any boy band. “The Eagles fine-tuned the whole machine,” conceded Poco’s Paul Cotton. “The difference between [Poco’s] Pickin’ Up The Pieces and [the Eagles’ first album] is huge. They could be played on AM and country radio and we couldn’t.”

Second, because Frey and Henley knew that pop success depended on what they rather snootily termed “Song Power” – that the Top 40 devil was in the micro-details of the smartly crafted compositions they began writing together on 1973’s wild-west concept album Desperado. “We bust our ass to make records,” Frey told Tom Nolan in 1975. “We agonise over the lyric. We analyse every ‘and’ and ‘the’ and ‘but’.”

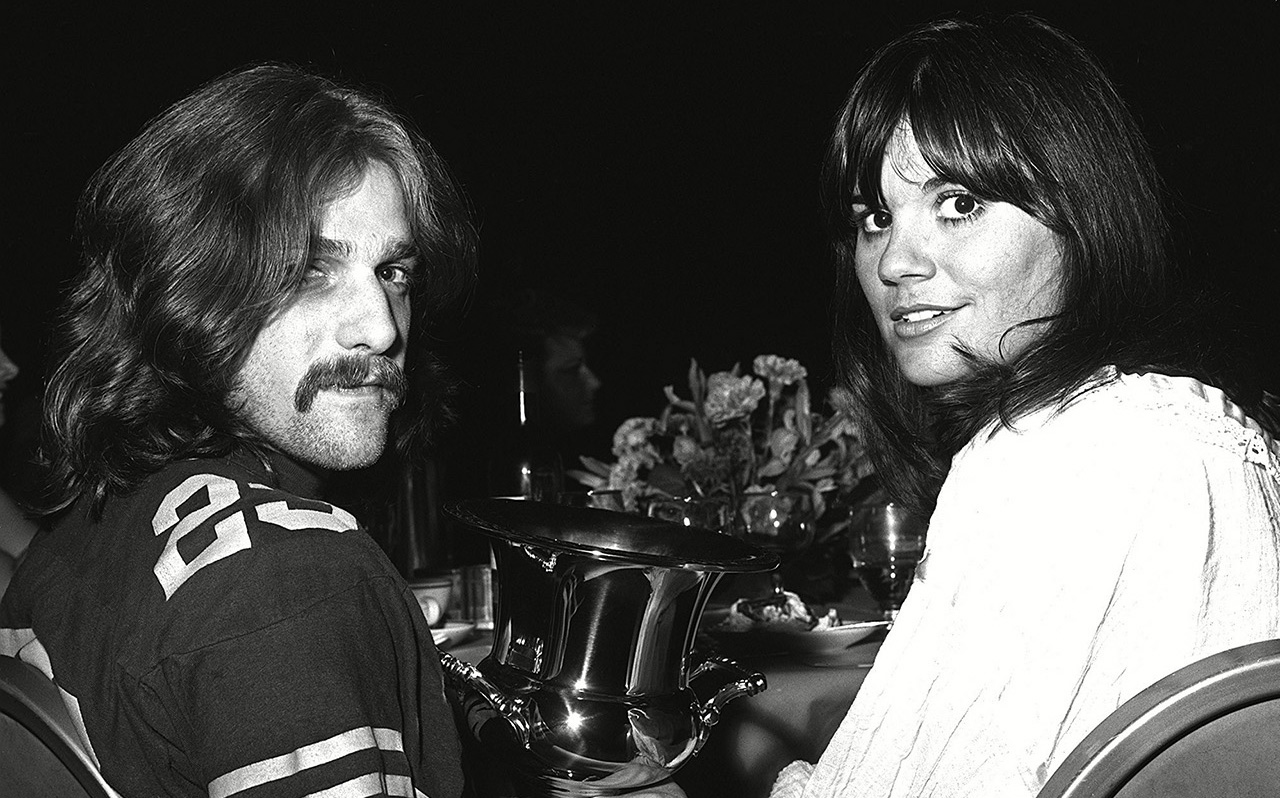

As obsessively as any of New York’s great Brill Building duos, these two slightly odd bedfellows – with input from Leadon, Felder, Walsh, Browne, Souther, San Diego singer-songwriter Jack Tempchin and ex-Poco bassist/harmonist Randy Meisner (ex-Poco) – relentlessly strove for pop perfection as they fine-tuned their limpid ballads and fast-lane rockers. (While we’re about it, let’s give a big hand to LA’s country-rock queen Linda Ronstadt, who in the summer of 1971 hired the Eagles as her road band before they were the Eagles and ever wrote a song at all.)

If the Eagles’ perfection struck Burrito Brothers fans as soulless and sterile, what did Frey and Henley care. They were living on Bel Air’s Briarcrest Lane in a hilltop house that had belonged to Hollywood goddess Dorothy Lamour, at least until their cocaine use spun out of control and the Butch Cassidy & Sundance Kid of rock’n’roll began to drive each other nuts. After the paralysingly tedious sessions for 1979’s The Long Run, the Eagles went their separate ways, only reconvening 14 years later for the tour that produced the 1994 live album Hell Freezes Over.

“When the Eagles broke up,” Frey recalled in 2012, “people used to ask me and Don, ‘When are the Eagles getting back together?’ We used to answer, ‘When Hell freezes over’. We thought it was a pretty good joke. People have the misconception that we were fighting a lot. It is not true. We had a lot of fun. We had a lot more fun than people realise.” In 1998, the Eagles were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

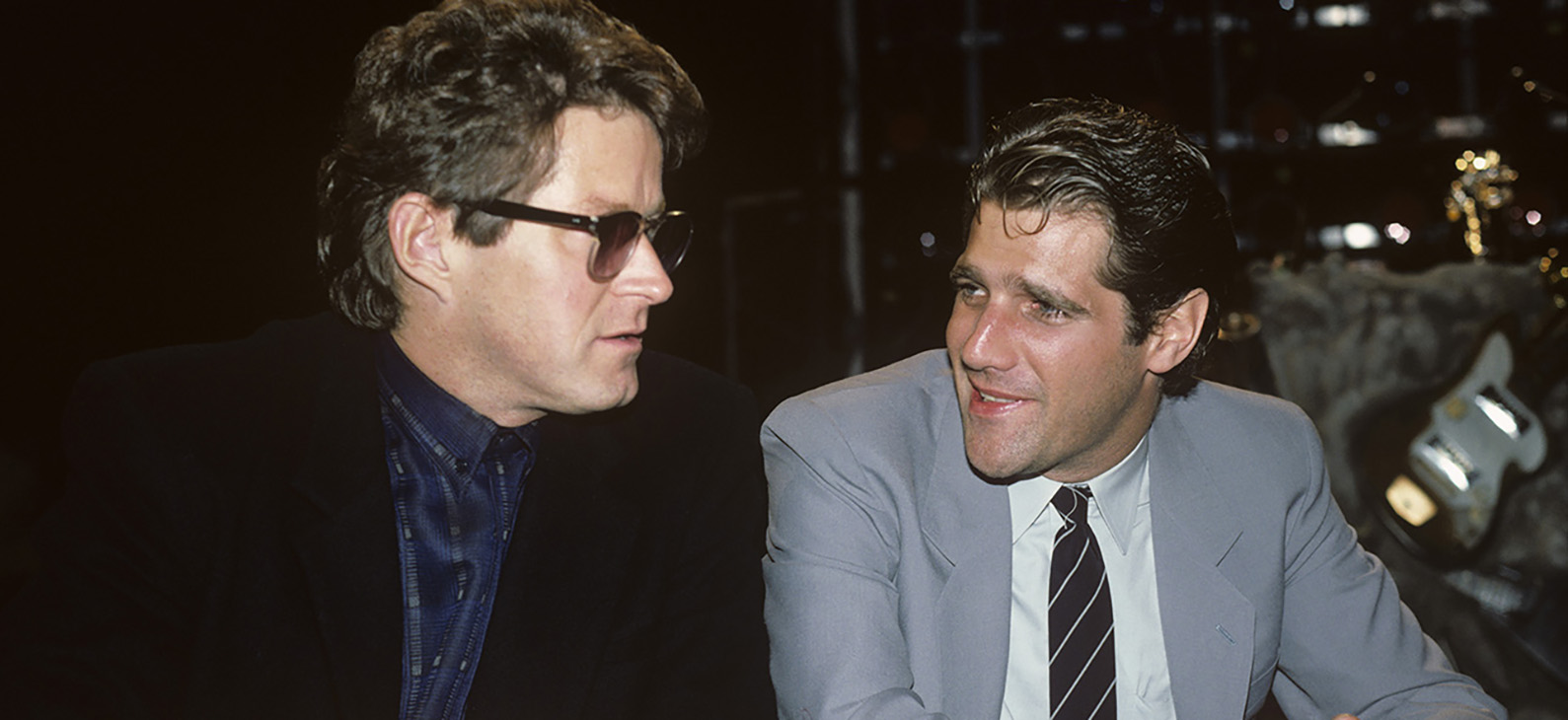

If Henley made better records than Frey after the Eagles – and also wrote better songs when the band recorded 2007’s Long Road Out Of Eden – Frey was never sore about it. In the 80s he scored Top Five solo hits with the Beverly Hills Cop theme song The Heat is On and the Miami Vice soundtrack song You Belong To The City, written with his old friend Jack Tempchin.

He also appeared in Vice in an episode inspired by Smuggler’s Blues, also co-written with Tempchin, and later had a cameo role in 1996’s Jerry Maguire, directed by Rolling Stone journalist Cameron Crowe, who’d written extensively on the Eagles in their 70s pomp.

In the 80s, Frey quit drink and drugs and became an altogether less arrogant man. And on the occasions when he looked back on the halcyon days of Hotel California, he seemed to have a healthier perspective on what it all meant. “There was a certain intensity,” he told former Elektra-Asylum president Joe Smith for the latter’s 1989 book Off The Record. “[But] perhaps a lot of it was bluff, because we were really just a bunch of skinny little guys with long hair and patched denim jeans and turquoise.”

Around 2000, Frey was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, the medication for which condition caused long-term problems with colitis, eventually leading to major intestinal surgery from which he never recovered. His last album was 2012’s standards collection After Hours. His final appearance with the Eagles was on July 29, 2015, in Bossier City, Louisiana, the last date of the History Of The Eagles tour.

Love them or loathe them – and for the punk insurgents of America’s Centennial year they rivaled Pink Floyd as Public Enemy No.1 – it remains hard to fault the sheer drive and commercial logic that enabled the Eagles to take their music to the limit. Industry commentator Bob Lefsetz has written that the press “didn’t know how to react” to Glenn Frey’s passing. “Because they had to be cool,” Lefsetz added, “[the press] couldn’t attest to what data tells us, that the Eagles are the biggest American band in history.”

“The Eagles were made to sell a million records,” said Elliot Roberts, some years after he lost the band to Irving Azoff. “They wrote to be huge.”