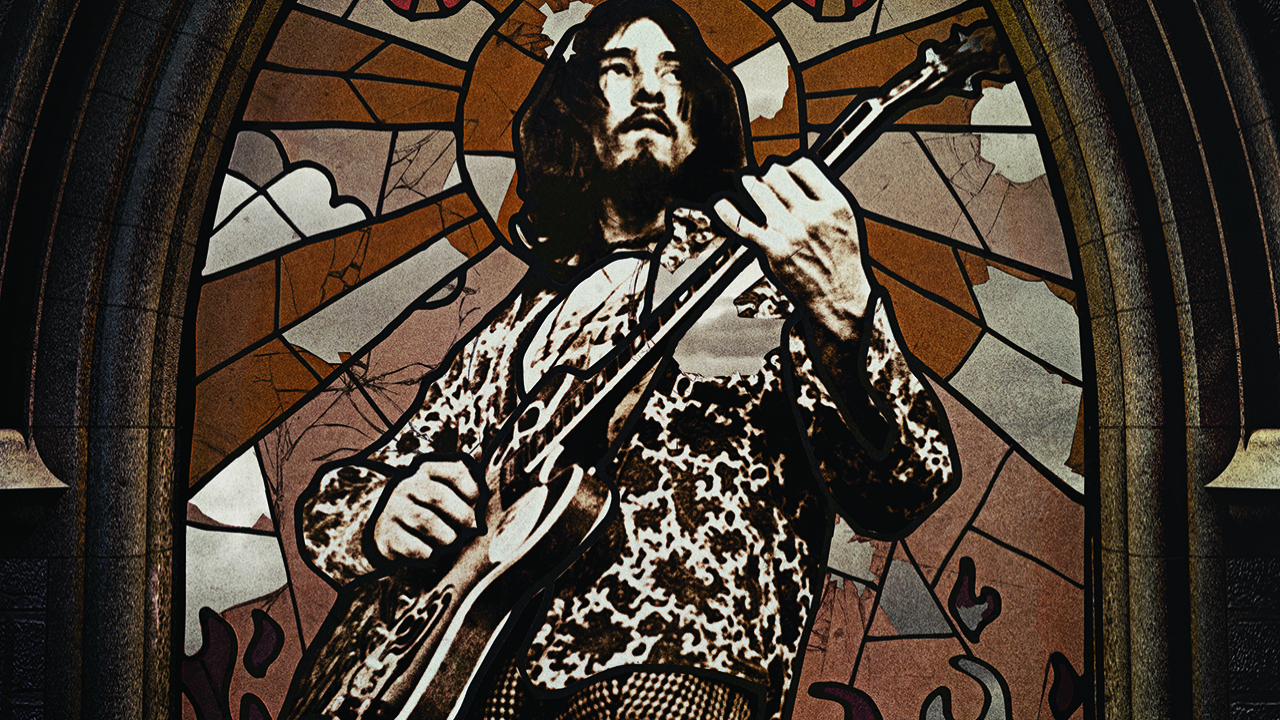

Glenn Schwartz stands before 80,000 people and he knows what’s coming next. It’s Saturday December 28, 1968, and the first day of the Miami Pop Festival is in full swing. The ads promise three days of “Beautiful Music”, and for the next 72 hours the Gulfstream Park Racetrack in Hallandale, Florida will host the likes of Iron Butterfly, Steppenwolf, Canned Heat and Fleetwood Mac, as well as Glenn’s own band, Pacific Gas & Electric.

The glorious weather makes for the perfect environment for this music, and PG&E’s blistering blues rock chimes with the mood of the festival, Schwartz’s Riviera semi-hollow guitar reflects the sun and flashes like a bolt of lightning, and as he finishes his final solo, the crowd roar their adoration. It happens wherever and whenever they play. The place always goes crazy, screaming and cheering.

Glenn eyes the crowd. It’s as if the whole world, a true sea of humanity, is before him. From his vantage point, he sees what many of them are doing, can smell what many of them are smoking, and knows what he and his fellow bandmates and the other artists at the festival have available to them. The world and all of its pleasures have truly been laid at his feet.

But something is troubling him. It’s been troubling him for a while. Now that he’s in a successful, in-demand band, he’s seen up-close the perils of everything this lifestyle has to offer. He’s friendly with Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison, and he knows the vices they struggle with. He grasps the microphone, and 80,000 people quieten down to hear what their new blues-rock messiah has to say.

“You know, my life seemed all right to me for a while, until I was no longer in control,” he says. “Then I was afraid. There was a revolution… and it took place inside me.”

He looks intently at the mob before him. Someone whistles. His bandmates nervously glance at one another. Glenn has done this before, grabbed the microphone and taken the performance off script, off the deep end, off the cliff. They’re in freefall now, and have no idea what he’ll do or say next.

With his guitar strapped in front of him, Glenn Schwartz points one hand to the sky and the other at the mass of people before him.

“The revolution that took place in me, it happened when I was saved through Jesus Christ,” he shouts into the microphone. “I accepted Jesus through a real need. I want you to know I’ve kicked drugs! No more drugs, man! And I’ll tell you something else. Christ is my saviour now. Yeah, Jesus has saved me. He can save you, too! Turn to Jesus, man – He’s the only way to heaven. Ask Him into your heart!”

Within two years, Glenn Schwartz had vanished from the spotlight, his head scrambled by fame, drugs or perhaps something deeper-rooted, to a religious commune in rural Ohio. He would spend the next decade there as a member of a Christian cult, the Church Of The Risen Christ, spreading the gospel of its leader, the Reverend Larry Hill, as part of the All Saved Freak Band.

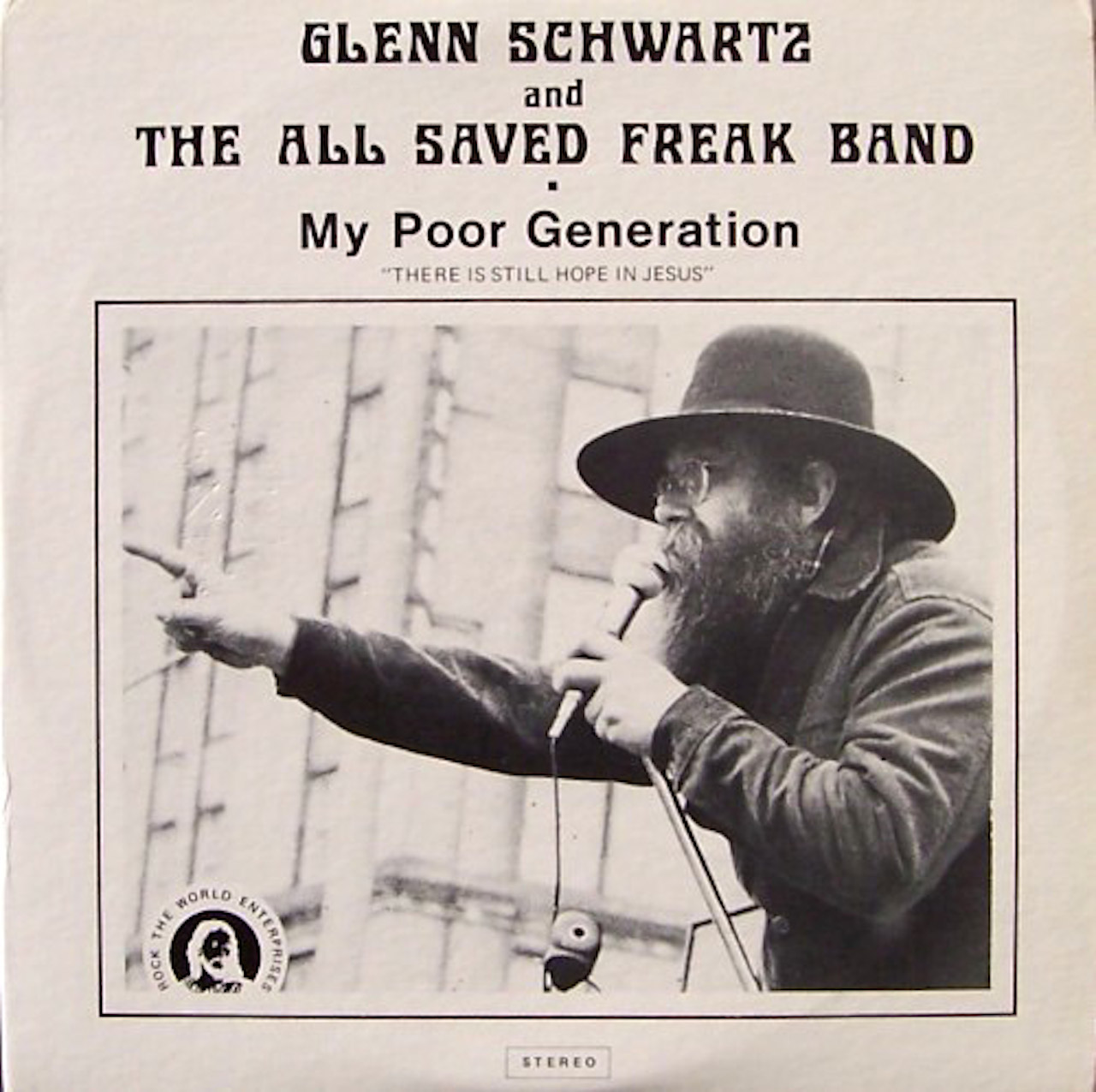

I first came across the All Saved Freak Band in 1976, when I saw an advertisement for their first album, My Poor Generation. The album had been released three years earlier, and it was billed to Glenn Schwartz And The All Saved Freak Band. I wondered how Schwartz – a guitar god-in-waiting who had been dubbed “the White Hendrix” – had ended up in this group whose album cover featured a bearded preacher wearing an Amish hat and pointing menacingly into the distance.

I ordered the LP, and it was pretty good. There was some intense blues rock on two songs Glenn wrote, Daughter Of Zion and Great Victory, but the rest of the music and lyrics were so unconventional that I wanted to hear the two other albums mentioned in the enclosed note – Brainwashed and the oddly titled For Christians, Elves And Lovers.

Over subsequent years, I began to hear and read rumours of the dark history of the All Saved Freak Band, the Church Of The Risen Christ, and especially Larry Hill. There were horrific allegations about what went on at their base, a farm on Fortney Road in Windsor, Ohio. They may have preached peace, love and rock’n’roll for Jesus, but for Glenn Schwartz, the All Saved Freak Band turned into a form of hell on earth.

“On the day you hear Reverend Larry Hill has died, remember to wear thick-soled shoes because hell will be stoked up extra hot,” one reporter told me. “He’s a psychopath. Larry Hill is the Devil incarnate.”

Glenn Schwartz was born on March 20, 1940 and raised in Euclid, Ohio. A musical prodigy, he started taking guitar lessons at the age of 11. By 14, he had won an international guitar-playing prize. He married young, at 21, to a woman named Marlene. They had two sons: the first, also called Glenn, was born in 1961; the second, Bob, followed two years later.

“Growing up, he was a great dad,” says Bob Schwartz today. “He was real friendly and kind of goofy. He’d do pratfalls to make everyone laugh. He acted like a big kid himself.”

Glenn spent most of his time picking up gigs with local bands, and he toured to earn money to send home to his wife and sons. But he wasn’t a domestic type, and he and Marlene would eventually divorce, remarry and divorce again (the second, and final split, came in 1972).

Schwartz passed through several local groups, including Frank Samson And The Wailers, The Pilgrims and Mr Stress Blues Band. But his break came in 1966, when Cleveland drummer Jim Fox was searching for a guitarist for his new band, The James Gang.

“Glenn came to listen to us play,” recalls Fox. “At one point, he came up on stage and started playing Jeff’s Boogie with us. He was phenomenal.”

The James Gang quickly became the city’s most promising band. Glenn played a natural-finish Epiphone Riviera hollow-body guitar that he had decorated himself. Among other things, it had a painted-on peace sign and flowers, together with the words “Help Me”.

Butch Armstrong was a 13-year-old budding guitarist when he first saw Glenn play with The James Gang in Cleveland. “The first time me and my friends saw Glenn, we all thought he looked like Jesus,” says Armstrong. “We didn’t know his name, so we just called him Jesus. He had hair down to his shoulders and wore sandals. There was a sound going around back then, something Clapton and the Stones were introducing to music, and we just couldn’t figure out how they did it. We could not get the licks right. Then we saw Glenn Schwartz and he knew how to do it, and he created that sound right in front of us! He used his fingers with the whammy bar and that was it. He became God to us in that moment. Everywhere he played, we’d go. Wherever Jesus went, we followed.”

Ramona Shay was a friend of Glenn’s. She recalls him enjoying the camaraderie of life in a band, and his enthusiasm for music. “On stage, Glenn would step out in front of the band and sometimes even move into the audience and play,” she says. “He played like he had been playing for centuries – never missed a lick, a beat or a note. He was spontaneous, with an honest simplicity and a tender straightforwardness. You looked into his eyes and never doubted that you could trust him with your life, your money or your wife. He was polite and respectful to all people.”

Glenn participated in everything that life in an up-and-coming band had to offer, including the sex and drugs. But like many young people at the time, he also began to explore different spiritual paths – Hare Krishna and Transcendental Meditation. He gave up eating meat for a while, though his spiritual questing never put a stop to the more carnal activities on offer to the band.

To the outside world, Glenn had it all. He was the hotshot guitarist in a band tipped for national success – he’d even been nicknamed “the white Hendrix” in local circles. Yet despite the attention and acclaim, there was a growing emptiness in his life, a nagging spiritual void that he couldn’t fill. It didn’t help that he was on the verge of exhaustion due to the constant touring, gruelling live shows and excessive drug use.

In November 1967, Glenn made the decision to leave The James Gang – and Ohio. He would head to California in the hope that a change of scenery would help him clear his head and calm his spiritually confused heart. The band’s local following was stunned.

“I was a big James Gang fan because of Glenn Schwartz,” says Butch Armstrong. “I was bummed out when he left the group. I didn’t think anyone could take his place.”

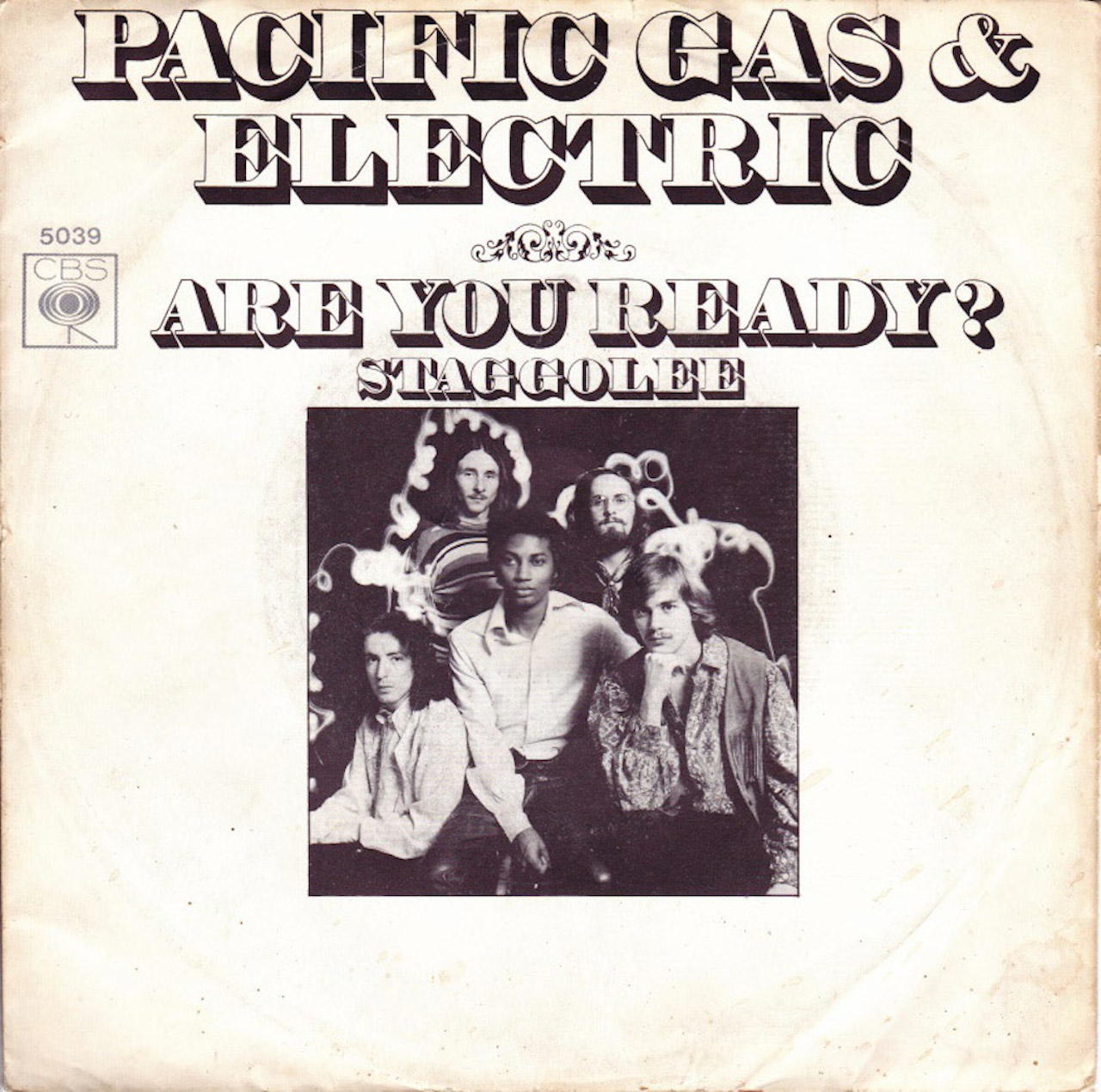

A friend drove Glenn out West, dropping him on a corner with just a suitcase and a guitar. At one of his first pick-up gigs in California, Duane Allman saw him and asked him to join the Allman Brothers. Glenn turned him down. Instead, he opted to throw in his lot with Pacific Gas & Electric, an eclectic multi-racial blues/soul/jazz/rock band, after meeting their singer Charlie Allen.

PG&E bassist and co-founder Brent Block recalls the first time he heard Glenn play. “We were all blown away by his talent,” says Block. “I had a very hard time keeping up with him. He was nearly a decade older than the rest of us, and had way more experience than we did. He was also an acrobat of sorts. He thought nothing of jumping off stacks of amplifiers and rolling around on stage. One night at the Cheetah Club, I saw him roll off the stage, fall maybe twenty feet, and he never missed a note.”

Glenn’s friend Ramona Shay recalls the guitarist enjoying his new surroundings. But by the spring of 1968, she detected a change taking place.

“Glenn’s developing spiritual interests in yoga and East Indian religious practices had been replaced with one that focused on the Bible. He told me later that he was feeling troubled much of the time, and I sensed he had become ungrounded mentally and physically. The music business in Hollywood was a pretty harsh, heartless and competitive scene, and I think the lifestyle was beginning to eat away at the sense of peace and love and balance Glenn had once had.”

What happened next has been debated by the people who knew him for decades. Was it the result of Schwartz tripping on acid, as some claim? Was it a consequence of spinning too fast on the carousel of success? Or was it simply a modern-day Road To Damascus conversion?

Whatever the reasons, the facts are unarguable. In the summer of 1968, Glenn strolled onto the Sunset Strip in Los Angeles and stopped next to a group of people listening to a pavement evangelist. The preacher talked about forgiveness, love and the chance for a clean slate – about being born again. It made perfect sense. Stoned or not, at that precise moment Schwartz chose Christ and quenched his spiritual thirst.

“I was finally blessed by mercy, for I heard the Gospel of Christ on Sunset Strip as a man of God preached Christ with tears in his eyes,” he told me years later. “Soon my tears joined his as he gave the invitation to pray, to come forward from the crowd, to accept Jesus, and I did so.”

Glenn’s conversion was instant and dramatic. It was if a powerful switch had been flicked on, and all at once he became a zealot for Jesus Christ. He began preaching to family, friends, other musicians, strangers, anyone within earshot. He also began expressing concern about the music he played and the power it had.

“A lot of rock music becomes idolatrous,” he said. “Psychedelic stuff can be like witchcraft. You know what I’m talking about? That psychedelic stuff can be like sorcery. A lot of times I find myself on an ego trip and I’m proud. You know, everyone in the audience bowing down to you. The music really gets far out, spaced out. But I pray before I go on and the Lord keeps it pretty well under control.”

His new-found faith did not sit well with his bandmates. Doing their best to ignore his evangelism, PG&E quickly recorded their debut album, Get It On. The sleeve featured a note from each band member, directed to the fans. Glenn’s read: “Together we can make everything all rite [sic], if you just clear your mind and let your heart be your guide. Pray for peace and may the good Lord Jesus be with you all.”

In September 1968, Glenn returned to Cleveland as part of PG&E. Former James Gang fans turned out to hear their home-town hero.

“Glenn absolutely played his ass off that first night back home,” recalls Rick Kalister, who had followed the guitarist when he was in the James Gang. “Much of his wild stage show was gone, but he transferred all that energy into his playing. I saw people weep when he played a slow blues; it was so sweet and beautiful.”

Glenn not only preached to his own band, he also evangelised to any of the groups PG&E played with. Bible in hand, he sought out Janis Joplin, Johnny Winter, Jimmy Page, Gregg and Duane Allman, and Fleetwood Mac’s Jeremy Spencer (who would undergo his own religious conversion soon afterwards). At one gig, Glenn walked to the front of the stage and threw tiny red Bibles out to the audience. Another time, when PG&E were supporting Led Zeppelin on their first North American tour, Glenn was out in front of the club handing out religious pamphlets. It wasn’t until one of his bandmates rushed outside and grabbed him that he realised he had made the band late.

He finally crossed a line during a show at the Fillmore West. To a mostly stoned audience, Glenn decided to stop playing and he begin preaching from the stage.

“We’re playing a slow blues number and the lyrics of the song were about dying from a sexually transmitted disease,” recalls Brent Block. “Glenn’s in the middle of one of his solos and all of the sudden, he starts exhorting the audience. I’m sure he felt that he had to reach people where they were. Still, a band on stage is a collective personality and not an individual using it as a platform to expose personal beliefs.”

Remarkably, Glenn stuck with the band – and the band stuck with Glenn – for two more albums, 1969’s Pacific Gas & Electric and 1970’s Are You Ready?. Brent Block says it was during the recording of the latter that Glenn announced to his bandmates that he “could no longer live the sinful life of a rock musician”. Shortly after the title track from *Are You Ready? *gave PG&E a Top 20 US hit, Glenn decided to walk away from his band for the second time.

Returning home to Cleveland, he moved in with his parents and brother Gene. With the latter, he formed a new band, the Schwartz Brothers, and they started to play weekly gigs at a bar in Cleveland Heights named Faragher’s. It was there that Glenn Schwartz met the Reverend Larry Hill.

- Black Oak Arkansas: the band who had it all, then gave it all away

- Every Home Should Have One: Grand Funk Railroad's Live Album

- Sir Lord Baltimore: "We were the first band to be called heavy metal"

- From cult heroes to global phenomenon: the unstoppable rise of Ghost

Larry Hill is central to Glenn Schwartz’s story, but he remains a shadowy and controversial figure. Born in 1935 in Ashtabula County, Ohio, he was a scrawny boy with a big mouth. His reputation for troublemaking was such that other parents told their own children to stay out of his way. In the late 1940s, when he was a teenager, Hill was involved in a horrific car accident that threw him out of the car with such force that his right leg was left on the back seat. After the accident, he moved around with the assistance of an ever-rattling pair of forearm crutches.

Hill earned a living as a travelling magazine salesman – a skill that would serve him well in the future. “To be successful at what he later did, he had to be the most charming, intelligent and caring man you would ever meet,” his son Tim told me. “And the whole missing leg thing would work in his favour because people would say: ‘This poor man is so upbeat and positive!’”

In 1955, he underwent a dramatic religious conversion. He believed he was called to be a pastor and a prophet. He quickly made a name for himself as a fiery itinerant preacher. He filled pews, and those who attended his services said he was one of the most dynamic and mesmerising preachers they’d ever heard. He was to preaching what Johnny Winter was to guitar playing: he let it all hang out, mistakes and all. He didn’t care. He just kept right on going as if it was all coming directly from God.

Eventually, Hill tired of his wandering lifestyle and decided to start his own church. In 1965, he claimed to have had a series of visions in which God revealed to him that a great war would soon break out in America. Hill, his wife and five children moved to a farmhouse on Fortney Road in the small, rural farming community of Windsor, Ohio, where they were joined by a group of more than 50 Christians who believed his end-time visions. Larry called his ministry the Church Of The Risen Christ and held services at the farm.

Joe Markko was 14 when he met Hill, and was one of the first people to move to Fortney Road. “When he began I think he had a truly humble heart before God,” says Markko today. “In all honesty, we felt ourselves unique by association with Larry. It was like God had provided a prophet and teacher just for us, and the closer we got to the prophet, the closer we were to God.”

Most of the theology Hill preached publicly was acceptable to mainstream Christianity, so no one in the small community gave his ministry a second thought. He said he was helping kids get off drugs and there was no reason to believe otherwise.

At the same time Glenn Schwartz was testifying before PG&E’s thousands of fans, Hill was on his own mission to convert people via music with his own band, Preacher And The Witness. Featuring Hill on piano and vocals, backed by members of his Fortney Road congregation, they purveyed mellow folk rock that fitted in perfectly with the burgeoning ‘Jesus Music’ movement – a groundswell of bands with contemporary sounds and an unswerving religious message.

Preacher And The Witness played street corners, coffee houses, churches. Hill began to incorporate additional instruments and a more contemporary rock sound. He decided they needed a new name. Joe suggested they were a group of ex-druggies and hippies, runaways and rebels – “bunch of saved freaks”. Larry zeroed in on the name and it stuck: The All Saved Freak Band.

The back room of Faragher’s was rocking out to Glenn and Gene’s version of Brick House when Larry Hill and Joe Markko entered. The latter says he will never forget his first encounter with Glenn playing live. “Though I’d heard his work on recordings, nothing quite prepared me for his live performance,” he says. “He blistered the air.”

When the set was over, Hill and Markko introduced themselves to Glenn and invited him to join them for a coffee. The three men began talking about religion and found they had much in common. Glenn was excited to find they had the same all-consuming fascination with the Bible as he did. Where his own religious passion had scared family and friends, these men were nodding their heads in agreement with whatever he said.

Hill told him about life on Fortney Road. About how they lived together and shared everything for the good of everyone. About Bible studies and the simplicity of communal living. Then he added the clincher: there was even a band he could play in, one that sang exclusively about Jesus.

The seeds had been sown, and Glenn started showing up occasionally to gig with the band. He made some visits to the farm on Fortney Road and invited his ex-wife and sons to join him. He also introduced his parents to Reverend Hill (neither they nor Marlene and the boys had any desire to follow Glenn’s path).

Glenn began playing with the All Saved Freak Band on a regular basis, and finally announced his decision to join the Fortney Road community full-time. His family and friends were so alarmed by his decision, and his constant, almost psychotic preaching, that to appease them he agreed to be committed to a psychiatric hospital for observation. After six weeks he was released. The doctors said there was nothing wrong with him.

In the early summer of 1971, Glenn Schwartz called Larry Hill: “Pick me up.” Joe Markko brought him to Fortney Road, where he officially joined the All Saved Freak Band and the Church Of The Risen Christ community.

Rumours began to spread that Glenn had joined some sort of fundamentalist Christian cult out in the farmlands. Soon, posters were plastered all over Cleveland announcing: “The All Saved Freak Band with Glenn Schwartz.”

Rick Kalister, who had watched Glenn in his James Gang and PG&E days, went to see the guitarist’s new outfit. “The band was always different,” he says. “It usually featured five or six amateur musicians singing songs about Christ. The whole point of the band was that they were all ex-hippie dopers who were now better off because religion had saved them. Then, in the middle of the show, Larry Hill would come out and threaten and insult everyone, telling us how we would burn in hell if we didn’t accept Christ. After, Glenn would be brought out with a big build-up that went like this: ‘He could have been a millionaire rock star like Jimi Hendrix! Some have called him the greatest blues guitarist in the world! But he gave it all up to serve Christ! Here he is, Glenn Schwartz!’”

Glenn could still play, but something had changed. The sweetness in his music was gone, replaced by bitterness. His hair was cut short and he wore Amish-style farmers’ clothes. As his philosophy became rigid, so did his music. “People used to cry with emotion,” says Rick Kalister. “Now they cried out

of concern for him.”

Still, word of the band spread. They played schools and churches, even prisons. They branched further afield – Native American reservations, mental institutions, migrant worker camps. Their flexibility allowed them to play a variety of music, though they always put evangelism first. As pastor of the church, Larry became the band’s leader by default. He was the moderator and preached at the end of each concert.

Glenn’s past life wasn’t always easy to escape. At one gig, Joe Markko recalls a woman running up to the guitarist, yelling his name. “That’s the most incredible guitar playing I’ve ever heard in my life!” she gushed. Without breaking his stride Glenn calmly responded: “I know. The Devil told me the same thing five minutes ago.”

Larry Hill was delighted with the reception they attracted. Inspired by Larry Norman – the pioneer of what today is known as Contemporary Christian Music, whose 1969 album Upon This Rock was considered the Sgt. Pepper of Jesus Music – he decided the All Saved Freak Band should record an album, and they entered the Cleveland Recording Studio to lay down My Poor Generation.

Alongside Glenn and Hill, the band featured Joe Markko on vocals, cellist/co-vocalist Kim Massman, Pam Massman on violin and vocals, Ed Durkos on rhythm guitar and Morgan King on bass. There were no drums on the album, and they weren’t really missed thanks to the vibrant rhythm guitar and piano that played against Glenn’s lead.

To Joe Markko’s unease, Glenn Schwartz’s name was featured prominently on the cover of the album – the group were billed as Glenn Schwartz And The All Saved Freak Band. But anyone expecting the raucous blues-rock of his old bands would have been surprised. The opening track, Elder White, featured some subdued, menacing guitar picking and Larry Hill’s rough and raspy voice: ‘Out of the backwoods of the Mississippi Delta came Elder White to fight for civil rights/Was he right?’ As the song unfolded, Glenn played a handful of notes in a masterful example of sustained tension. It ended on a sombre, sobering note with all the instruments silenced except for the piano and Hill’s voice: ‘Remember the one they crucified/His mother was a Jew.’ It was, says Joe Markko, a song that chimed with the times.

“Civil rights was a very large issue at the end of the sixties,” he says. “The experience of several band members was deeply steeped in the black churches. Elder White ended up being a song that’s against prejudice in any form.”

Glenn displayed his firepower on only two songs: Great Victory and Daughter Of Zion, both first-rate heavy blues rockers. Tellingly, he wrote both, and sang lead on the former (Larry Hill took vocals on the latter).

With the release of My Poor Generation on their own label in 1973, the All Saved Freak Band increased their visibility beyond Cleveland without having to tour. Now there was a record to mail instead of having to send the band out on the road so often.

If anyone thought “the white Hendrix” would receive special treatment at Fortney Road, they were mistaken. Years later, Glenn still referred to Larry Hill as “The Preacher Man”.

“The Preacher Man would call me ‘Star’ at the farm,” Glenn told me. “He said I thought too much of myself and needed a good beating, said there could be no stars at Fortney Road. That one-legged preacher… he smacks you around and beats you.”

Another ex-member of the cult, who wishes to remain anonymous, has even darker memories of their time there. “When I describe a typical day at Fortney Road, it feels – and must sound – incredible, as if it never could have happened this way, as if no one could have endured what we did, day after day, for months or years.”

On Hill’s instruction, Glenn and his fellow Fortney Road residents had to be up at four each morning or receive a beating or another form of punishment. One time, he and all the men failed to awaken in the morning and they had to run 10 or 15 times through a pond that was three-feet deep – and this was in the middle of winter.

Once they were up, the men rushed to feed all the animals and clean their stalls as quickly and thoroughly as possible while the women hurried to the farmhouse to prepare breakfast. When the quick morning meal was over, the men would head off to their jobs. Glenn was a skilled mechanic and worked at an automobile repair shop. All of his earnings were handed over to Hill. After the long workday, dinner was available – though most members of the church were encouraged to fast. They believed it brought them closer to God.

“I once went twenty days without food because I couldn’t please God,” Glenn recalled. “I had too much ego. The one-legged preacher would always warn us that we were going to lose out if we didn’t obey. So I’d fast Monday but it wasn’t enough so I’d fast another day. I was always under fear so I fasted all week and then eat on Saturday. Man, I was so tired, I could barely push the pedals on the truck.”

Bible study often continued until one in the morning so Glenn, like everyone else, barely managed to survive on only three or four hours of sleep each night. In 1972, three members of the cult, including Larry Hill’s son, Brett, and Joe Markko’s brother, Randy, died in two separate road accidents, both of which involved drivers falling asleep at the wheel of their vehicles. It prompted Glenn Schwartz to write a song, Dark Clouds Rollin’ Over 1972, to express the grief of the community (the song was never recorded).

Hill ran the All Saved Freak Band with a rod of iron. “He would yell and belittle you if you didn’t play the way he wanted,” says bassist Morgan King, who left the farm in 1975. “For me, the music did help break up the everyday drudgery.”

Glenn himself endured numerous beatings. Hill owned a six-foot-long whip he named the White Judge, with which he would dispense God’s justice freely. “I’ve seen the rod of His wrath,” Glenn told me, “and have been beaten with it.”

Glenn’s family were increasingly concerned. His son, Bob Schwartz, recalls being allowed to visit his father at Fortney Road, but he was never left alone with him. “We’d go into this big living room and people were all around him,” says Bob. “He could never come out and see us by himself.”

The Schwartz family were convinced that Glenn had been brainwashed, and that Larry Hill was controlling his life. “My son’s mind has been broken down by that man,” Glenn’s mother insisted. “Larry Hill wanted him for his guitar talent. We will continue to try to get him back.”

They were as good as their word. In February 1975, when Glenn was 34 years old, Hill gave him permission to have a rare meal with his family. Glenn’s parents and brother Gene met him at the local Howard Johnson’s. Outside in the parking lot, when the meal was over, Schwartz was suddenly grabbed from behind and his father, William, snapped a pair of handcuffs on his son, put him in the back seat of a car and quickly drove to

a nearby motel, where he left his son in a room.

Soon the door burst open and a 45-year-old African-American man approached him. This was Ted Patrick, who had made front-page headlines for kidnapping and ‘deprogramming’ cult members. Glenn’s parents had reportedly paid $1,400 to have him deprogramme their son.

For two days, Schwartz was held captive at the Gateway Motel. Bob says, “When we arrived at the motel room, we saw that Dad was tied to the bedpost. He was glad to see us it, but it was awful seeing him tied up like that and we didn’t really understand what was going on.”

After 48 hours, Schwartz was finally released. He immediately returned to Fortney Road.

The kidnapping of Glenn Schwartz by his own family was a talking point around Cleveland. Many viewed the Fortney Road commune as a benign place where local teens were helped to kick drugs. Some people were outraged – what kind of people would forcibly remove their son from a Christian ministry?

But a handful of people were beginning to suspect that something wasn’t right about Larry Hill and the Church Of The Risen Christ. John Hansen, an executive at Cleveland Records, was no fan of Hill. “He gives bad vibes,” he said. “He comes in here with his girls and they hold prayer meetings. It’s a big con. I see a lot of freaks. Some of them I suspect come in and smoke pot, and I wish they’d get out of here. But this guy is weird.”

Rock critic Anastasia Pantsios agreed. “Larry Hill is an opportunist,” she wrote in The Plain Dealer. “He turns the people in his congregation into zombies with no minds of their own.”

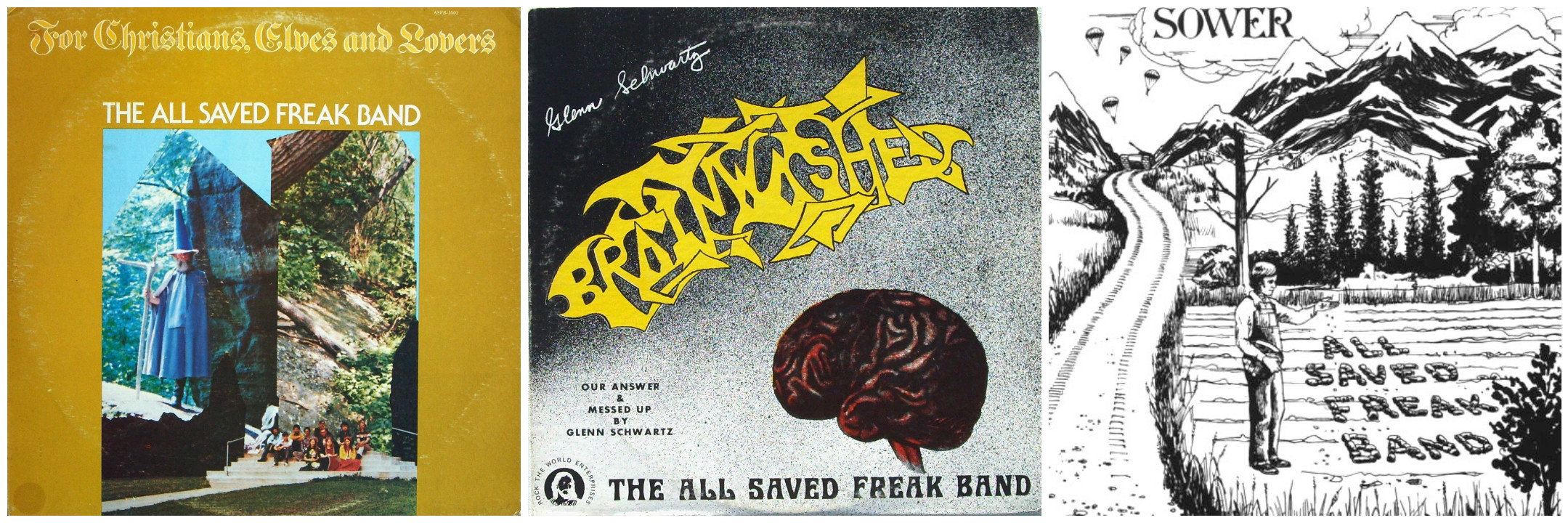

The All Saved Freak Band’s second album, 1975’s hard-rocking Brainwashed, was named as an intentional response to their critics. “They had said that our conversions were nothing more than being brainwashed, so the entire album was dedicated to that issue,” says Joe Markko.

The second track on Brainwashed was written by Joe and titled Ode To Glenn Schwartz. It featured an electric guitar and bass playing the same riff, joined by the cello after the lead break. Its unique sound was heightened and enhanced when Larry Hill’s hoarse vocals whispered along with the last verses: ‘I know what I must do, Lord kill my pride/I got no place to run to, no place to hide/My sins are before me, on the altar they lay/I know they’ll destroy me – let us pray.’

“Those words were designed to describe what was happening in Glenn’s life,” Joe explains. “He contemplated abandoning his faith after all the rejection from his family and friends. They were a description of the way he was treated – the kidnapping, everything he had gone through.”

The centrepiece to Brainwashed, and the track that truly showed off Glenn’s talents to their fullest, was the seven-minute Don’t Look Back. It featured some of his longest and most fluid leads.

So much guitar fire clearly concerned Larry Hill. “When we’d finalised the Brainwashed album, Larry told me, ‘This is as far as we go,’ meaning this is as far as we’re taking the rock or contemporary sound,” says Joe Markko. “That’s why the following recording has a different edge.”

Indeed, Brainwashed wouldn’t be released until 1976 – following another, altogether quieter All Saved Freak Band album. The oddly titled For Christians, Elves And Lovers reflected Hill’s obsession with JRR Tolkien’s Lord Of The Rings. It included just one genuine rock song, Water Street, written about an incident when the band played a bar in Kent, Ohio, after the Kent State University shootings in May 1970, in which four students were killed by police. Schwartz provided a snarling guitar solo for the track, as Hill celebrated a victory over Satan as the ‘naked feet’ of hippies came to the Lord.

Typically for the All Saved Freak Band, the album’s gentle music masked a fire-and-brimstone message. Stephen laid a foundation for dire warnings about the end times and the appearance of the Antichrist. Another track, Valley Of Decision, was a reminder for people to pay heed to the teachings of the Bible in the face of impending doom: ‘Read long and hide it with prayer in your heart/And if you don’t pray an hour a day, then you’d better start.’

The lyrics gave some insight into the level of oppression and fear that Glenn and others at Fortney Road suffered under. Rob Galbraith produced all of the All Saved Freak Band’s records, although he quit For Christians, Elves And Lovers before recording was complete. When it came to working on the albums, he was invited to stay at the farm and forego the expense of a hotel room.

“Something just didn’t seem right,” Galbraith says today. “I remember people were up really early, roaming around at four. And people kept disappearing from album to album. I know that Morgan left before I quit working on …Elves. I asked where he was and they never really answered. ‘He just left,’ is all they would say.”

Released in the autumn of 1975, For Christians, Elves And Lovers didn’t garner the acclaim or sales that Larry Hill had expected, but Brainwashed – recorded before …Elves but released afterwards – was a different matter. Its success was partly down to a DJ-only single featuring Ode To Glenn Schwartz and Seek Him. It suggested that the appetite for Glenn Schwartz’s guitar playing was still there.

Demand for the band grew. They spent much of late 1975 and 1976 on the road. There were high-profile appearances at the New Orleans’ Mardi Gras and as part of the musical line-up at the Summer Olympics in Montreal. Their shows were equal parts rock concerts and evangelical gatherings – members gave testimonies between songs about their faith, and Hill held an altar call as the end of gigs, where concert-goers had the opportunity to convert to Christianity. But if the band’s public face was simply that of any other travelling Jesus Music band, what lay behind the mask was altogether darker. And the mask was about to be pulled away.

The abuse that Glenn Schwartz and more than 50 men, women and children suffered at Fortney Road was finally exposed in 1978. In April of that year, police arrived at the farm to serve arrest warrants to Larry Hill and his right-hand woman, Diane Sullivan. The charge was alleged child abuse. A year earlier, on Wednesday, February 16, 1977, Hill and Sullivan had viciously whipped and beaten an 11-year-old girl, Bethy Goodenough, after years of physical and sexual abuse. Two female members of the cult had witnessed the beating and finally went to the authorities to report what was really happening at Fortney Road.

The police were unable to locate Hill – he was hiding in Pennsylvania. Diane Sullivan was ultimately convicted of a misdemeanour child abuse violation: “Miss Sullivan did cruelly abuse and administer corporal punishment in a cruel manner and for a prolonged period.”

How did this abuse go unnoticed by the people who lived at Fortney Road? The truth is that some people were genuinely unaware of what was happening. One former cult member, who wished to remain anonymous, puts it down to “naivety”. But others were aware. “You weren’t allowed to talk about it,” one former member says. “It was just a known thing that it had happened. It was totally unheard of to talk openly about the beatings any of us received. It would have been like a death sentence to say anything.”

In the wake of the police’s visit, the group fractured. Soon, only a dozen adults and children remained at Fortney Road – Glenn among them. Hill himself remained in Philadelphia, and would make only sporadic visits to Fortney Road.

Why hadn’t Glenn Schwartz left the Church Of The Risen Christ – and why did he stay for nearly two more years after the police raided it? No one I spoke to knew, but the most likely reason was fear of God – and fear of Larry Hill. The only way to find out was to talk to Glenn myself.

Glenn Schwartz rarely gives interviews or allows his photo to be taken. I knew he lived with his brother, Gene, in the house they grew up in. I plugged the address into Google and the phone number came up. I called, got the answering machine and left my information.

My phone rang at 8pm that same evening. “Is this Jeff? This is Glenn Schwartz.” For a second, I thought it was a joke, but I recognised his gruff voice from the All Saved Freak Band LPs I owned. I was stunned that he had returned my call, but I quickly started asking questions. It was the oddest conversation I had ever been a part of.

Talking to Glenn was like rapidly tuning an old radio dial, jumping from elevator music to death metal to smooth jazz to 50s pop. He was a pinball, bouncing off every question I asked, then hitting me with another one. Sometimes he would yell his answers, sometimes he recited scripture, sometimes he whispered Bible warnings to me.

For two and a half hours, he let it rip. And the entire time I spoke with him, I couldn’t shake the thought that I was listening to Larry Hill channelled through Glenn Schwartz. But he would not mention Hill by name, referring to him as “the one-legged preacher” or the “Preacher Man” or “the Dark Man”. When he talked about his time on Fortney Road – and it was clear he didn’t want to talk about it – he often made it sound like it was a positive experience for him. He said that much of the teaching was good, but he and the others who lived there were not strong enough to take it, or reach the level of perfection that God demanded.

And yet he would also acknowledge to me that something was terribly wrong about Fortney Road, and that he had seen and experienced things that he knew were depraved. I noticed his tenses would change, sounding at times as if he were still living there and not recalling events from decades ago.

“That one-legged preacher… he put a terrific burden on the women and the men,” he said at one point. “The Word condemned me all the time. Some people would eat only dog food to humble themselves, to keep themselves low. I would slap and punch myself in the face to punish myself so I wouldn’t lose out in the end. I was always under fear. Fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom!”

So it was fear that kept him there. But then what changed? Why did he leave Fortney Road?

“I wanted to endure to the end,” he said. “Most of the people couldn’t take it and left the farm or God struck them down, just like the Preacher Man said He would. You have to stay humble or God will beat you down! But I didn’t last at Fortney Road. I just couldn’t make the grade, so I had to leave.”

Unlike his arrival at Fortney Road, Glenn’s departure was low-key. Former All Saved Freak Band member Carole King Hough says one day during the early spring of 1979, she answered the phone and Glenn’s parents were on the line.

“They were so excited,” she says. “They told me that Glenn had left the farm. He walked off the property one day and kept on moving until he ended up at some bar. He saw a motorcycle parked out front and it turns out it was his brother Gene’s.”

Gene immediately took Glenn home to their parents who, concerned that their son might return to the cult, made sure he was surrounded by sympathetic friends such as Carole King Hough and her husband Mike. Butch Armstrong remembers calling Glenn and spending several minutes trying to get past Glenn’s father. “They were worried about Larry Hill coming around again, trying to contact Glenn,” he says.

And they had every right to be. Larry was furious about losing his most prized asset. He even showed up at one of the first gigs Glenn played after leaving Fortney Road. “The Preacher Man came to see me play and I remember him back from when I lived on the farm,” Glenn told me. “He had books on witchcraft that I saw and I felt the doom coming over me when I saw him.”

Glenn didn’t stay too long with his parents, instead living and sleeping in his car until someone torched it while he was playing a show. Friends let him stay in a broken van parked out behind a body shop after that. Others rallied around him too. In 1979, Joe Walsh who replaced Glenn in the James Gang, invited him to shows on the Eagles’ Long Run tour. In early 1980, Pacific Gas & Electric, reunited for a show in California, and Glenn was involved.

But even though he was free of the commune, it wasn’t easy to escape the shadow of Larry Hill. In 1980, the preacher released the fourth and final All Saved Freak Band album, Sower, made up of songs recorded during the 70s. The band themselves no longer existed, though you wouldn’t know it from Hill’s liner notes – it read like Glenn was still part of the Fortney Road community. While the guitarist did play on the album, he had no writing credits. In fact, during his time with the All Saved Freak Band, he only contributed four songs.

Today, Glenn and his brother Gene still play occasionally around the Cleveland area as the Schwartz Brothers. Glenn also plays with other pick-up bands, and his son, Bob, often plays drums with his dad and uncle. “We get along okay,” Bob says. “I have no bad feelings toward him. He’s more laid-back now, too, and while he still preaches, he’s not as judgemental or harsh as he used to be when he first left the farm.”

He is still a deeply religious man, and he remains damaged by his own past. People who have seen him play in the past talk about how he would walk around a venue seven times to spiritually prepare himself for a show, or the time he was interrupted mid-sermon by a fellow Christian shouting “God is love”, only to shout back: “No! God is judgement!” Some describe him as damaged; psychotic even. Others say he is friendly and warm, willing to pass on his knowledge of the guitar – and of God.

But one thing that remains unchanged is his God-given talent. In 2008, former Talking Heads frontman David Byrne travelled to Ohio to see Glenn play live. “Glenn Schwartz may have lost his mind, but his fingers are firing on all cylinders,” Byrne said afterwards. “Between amazing and inventive Hendrix-like solos, he admonishes the audience and prophesies ‘blood on the moon and war in America’.”

“Glenn was always such a good man with such a gentle, tender heart,” says his former All Saved Freak Band colleague Joe Markko. “I think if Glenn had never encountered Larry Hill, he would have made music that could have really influenced his entire generation.”

Fortney Road: Life, Death And Deception In A Christian Cult, by Jeff Stevenson, is available now.