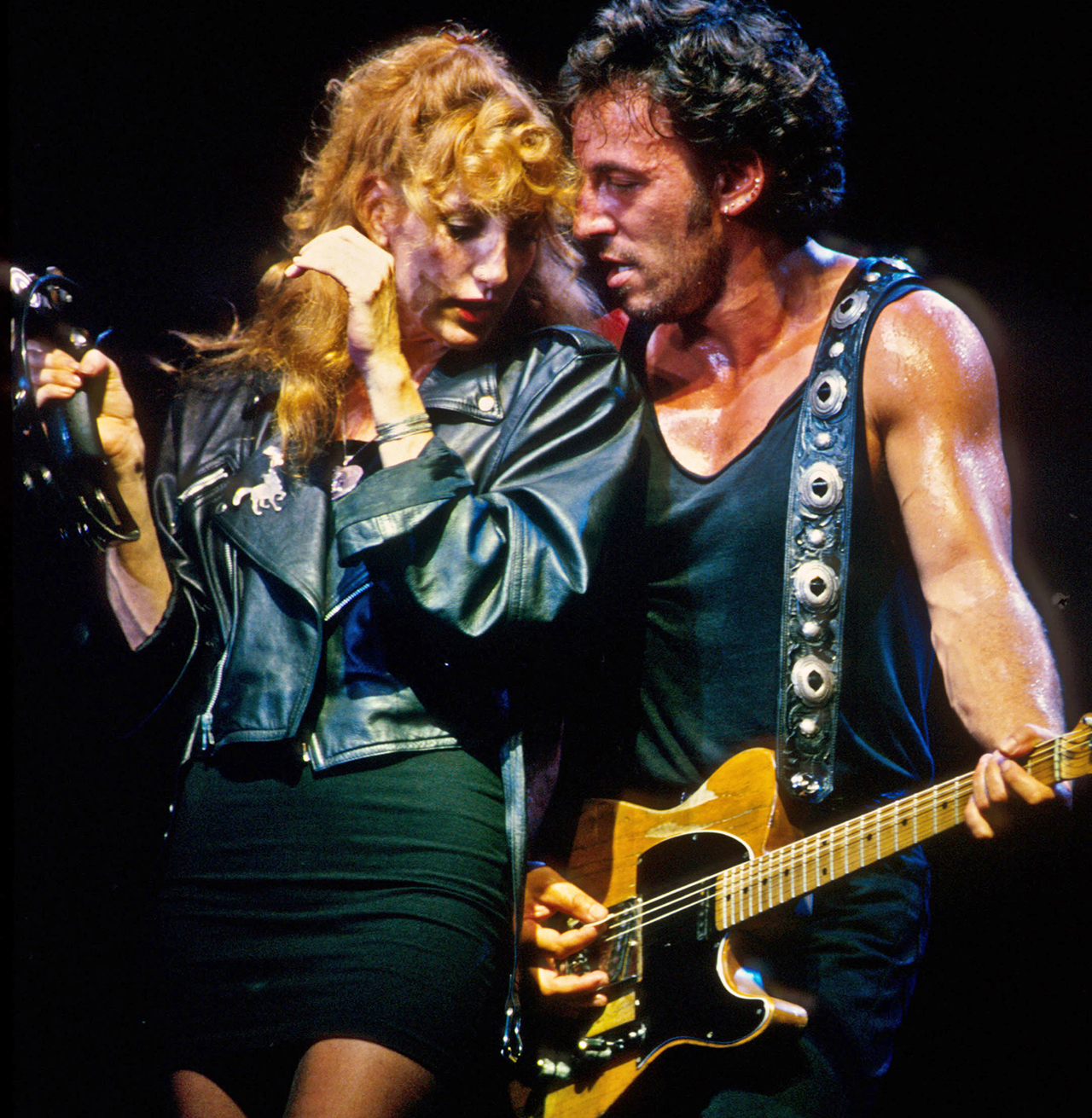

On the warm evening of October 2, 1985, it was approaching midnight when Bruce Springsteen introduced his new wife to some 80,000 curious onlookers during his concert at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. Stepping out from the wings, Julianne Phillips was a 25-year-old model and actress from a well-to-do Chicago family. She and Springsteen had met the previous October, and were married the following May during a short break from the 15-month-long tour to support his most recent and mind‑bogglingly successful album, Born In The USA.

Springsteen took his wife of five months in his arms and danced with her to one of his songs under the harsh white stage lights. He had first danced to it not much more than a year ago with another aspiring young actress, Courtney Cox, in the video that launched Born In The USA into the stratosphere. Tonight, on this 156th and final date of the tour, as on every other night of it, Dancing In The Dark was the vehicle with which Springsteen and his seven-piece E Street Band drove their audience to a euphoric peak and then held them there for almost two hours more. And this in spite of the fact that its lyrics spoke of nothing so much as self-loathing. “Had to save the last dance for her,” Springsteen told the roaring crowd as the climactic notes of the song reverberated around the vast stadium. He was smiling then, seeming to bask in the glory of it all.

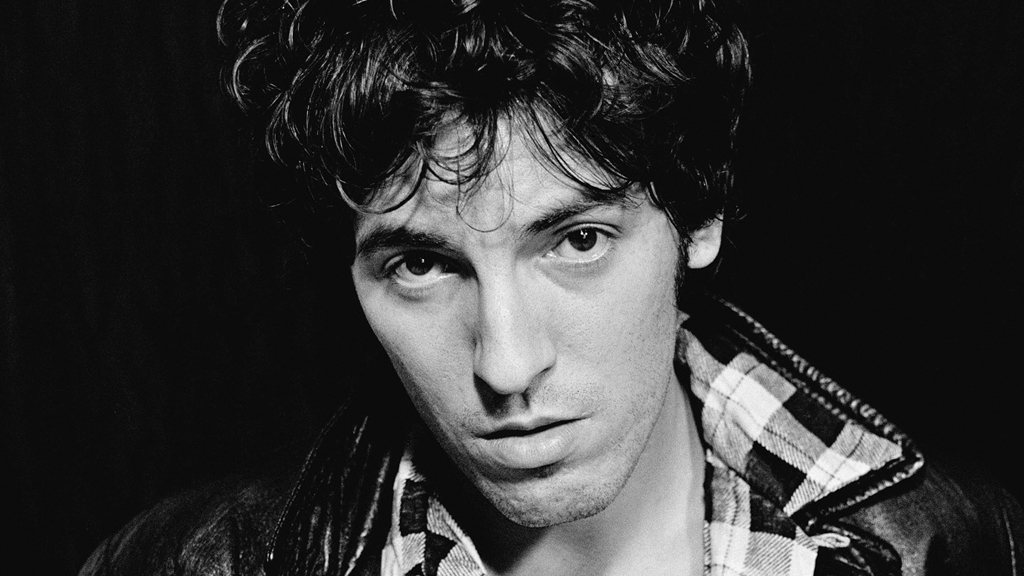

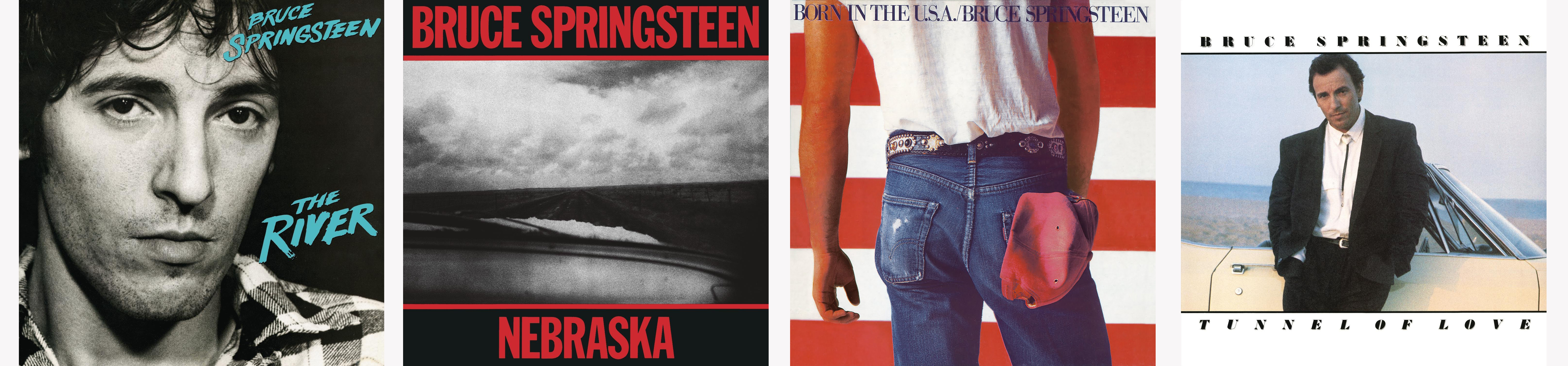

And as well he might. Born In The USA had come along right on the heels of a dark period in both Springsteen’s own life and for Americans in general. The years immediately preceding its release had seen the US economy slump, jobs vanish, and out there in the heartlands these were the worst times folks could recall since the days of the Great Depression of the 1930s. Springsteen, who was susceptible to his own depressions, had for his part sunk into an existential crisis following the tour to promote his fifth album, The River, and with which he had kicked off the new decade. He articulated as much on his next record, 1982’s Nebraska, a stark, solemn collection of songs that he recorded apart from the E Street Band, who had been the bedrock of his music since the mid-70s.

Nebraska had sounded like whispered moans in the dead of night. The ordinary Joe characters with which Springsteen populated Born In The USA were often as not fighting the same internal and external battles as on its predecessor, but musically this was an altogether different and more welcoming beast. Filtered through the returning E Street Band, Born In The USA was instead rousing, uplifting, as slick and sleek-sounding as a sports car, and balm to tend the battered psyches of millions of Americans.

It arrived at precisely the right moment too, just as the country was returning to prosperity and entering into a new era of consumption and consumerism. Like Michael Jackson’s Thriller before it, and Madonna’s Like A Virgin and Prince’s Purple Rain in that same year of 1984, Born In The USA proved to be a commercial juggernaut. It was mined for multiple hit singles, the videos that accompanied them given saturation coverage on the then three-year-old MTV. Together, Springsteen, Jackson, Madonna and Prince were rewriting the rules of pop superstardom, becoming brands in their own right. And it was through their aspirational promo videos that each of them reinforced their brand values – and where Springsteen stood apart. Whereas the others appeared aloof, like alien beings from some glamorous, far-off galaxy, Springsteen dressed in worn jeans and a T-shirt and sang about the trials of the working man. He conveyed nothing as much as down-home values and an old‑fashioned belief in the redemptive power of rock’n’roll. Uniquely, Springsteen was embraced as a folk hero, not least by the country’s then President, Ronald Reagan, who notably mistook Born In The USA’s barnstorming title track for a patriotic blessing of American values.

So there Springsteen was at the Coliseum, riding the crest of a wave and having ascended to become a true American icon. No wonder he looked in that instant as if he were about as content with the state of things as one could be. But not five years later he would end the decade, one that had brought him untold fame and wealth, consumed once more by black thoughts and self-doubt. His marriage would be wrecked, and he would have cut loose the E Street Band by then too. All of this could not have been telegraphed better than by one of the last songs he had written for Born In The USA, and with which he sent the Coliseum crowd rejoicing off into the LA night. ‘Glory days,’ Springsteen sang to them, “Well, they’ll pass you by… in the wink of a young girl’s eye…’

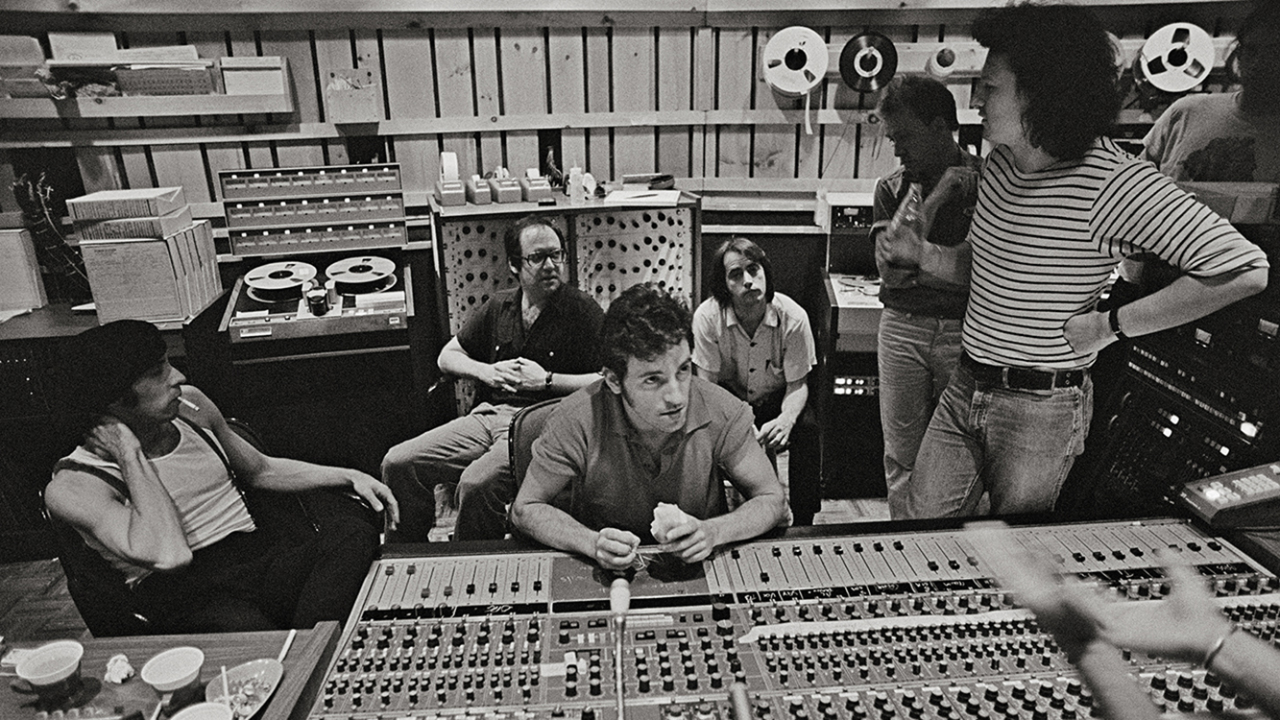

The strongest tie binding together Springsteen and the E Street Band was almost broken late on an earlier night in March 1979. At that time, Springsteen and his then six-piece backing group were just starting the recording of The River in the gymnasium-sized main room at the Power Station studio in downtown Manhattan. Springsteen had arrived intending to work fast and cut a high-octane, primal-sounding record that encapsulated the intensity of their live shows. “We figured we’d throw up the room mics,” he told biographer Peter Ames Carlin, “and make a lot of rock’n’roll noise.”

But things didn’t quite work out that way. Springsteen was instead prevaricating over the most infinitesimal details, just as he had done during the making of their two previous records together, each of which he had extended into tortuous ordeals.

This particular evening he was likely fretting over the timbre of Max Weinberg’s snare drum, or when precisely to have saxophonist Clarence Clemons come in on a certain track. Or any of the other infinite conundrums that buzzed through his mind whenever he was occupied with capturing his music on tape. Steve Van Zandt, the E Street Band’s guitarist since 1975, had run out of patience with this maddening routine and snapped. “Listen,” he said to Springsteen, seething with pent-up frustration, “I’m sorry, but I can’t do this again. You carry on, but I quit.”

The voluble Van Zandt was a veteran of the bar bands Springsteen had led along the New Jersey shore in the late 60s and early 70s and the nearest thing he had to a close friend. Losing him at this crucial juncture would be for Springsteen like cutting off his own right arm. And so he moved at once to placate Van Zandt, inviting him to produce the record alongside himself and Jon Landau, Springsteen’s bookish manager. Van Zandt acceded, and Springsteen pressed on with a process that would ultimately drag on for 18 months at a final cost in excess of a million dollars. When he was eventually done, The River turned out to be a transformational double album, widening the scope of his music and paving the way to Born In The USA. Right then, though, Springsteen was at a crossroads. Approaching 30 and moved to contemplate the point he had reached in his personal life, he was deeply unsettled by what he found himself facing up to.

Raised in the blue-collar town of Freehold, New Jersey, Springsteen was the eldest of three children born to father Douglas, a World War Two veteran and sometime bus driver and prison guard, and mother Adele, a legal secretary. Their only son, he grew up something of a loner, often at odds with his buttoned-up father and almost everyone else he came into contact with. Music lit him up like nothing else. His first band was a bunch of high-school Beatles wannabes called The Castilles, whose drummer went off to fight in Vietnam and didn’t come back. Springsteen skipped the draft, dropped out of college and passed through a bunch of other short-lived bands before striking out on his own. He was signed to Columbia Records in 1972 by John Hammond, and became the latest in a string of earnest young singer-songwriters to be touted as the ‘new Dylan’. His first two albums for the label were overly intricate, verbose affairs and both flopped, but then he hit pay dirt with his third, in 1975.

On Born To Run, Springsteen was able to imagine what Roy Orbison might have sounded like fronting Phil Spector’s Wall Of Sound. Propelled by its title track, it achieved platinum sales in the US. That feat was matched by its less grandiose, more downbeat follow-up, Darkness On The Edge Of Town. By then the E Street Band had also coalesced around Van Zandt, Clemons, Weinberg, bassist Garry Tallent, organist Danny Federici and pianist Roy Bittan.

The sales of those records, though, still paled next to those of such 70s behemoths as Led Zeppelin, the Eagles and Fleetwood Mac. And although he could pack out multiple nights at arenas on his native East Coast, elsewhere across the US his fan base was patchier, less frenzied. And apart from one ill-starred visit to London in 1975, he had not set foot outside his homeland. He was also, to all intents and purposes, broke. Work on Darkness had been held up for a year by the court case he had fought to free himself from his first manager, Mike Appel, and which had frozen his assets.

Returning from the Darkness tour at the start of 1979, Springsteen sequestered himself in a rambling farmhouse in the rural New Jersey township of Holmdel. He was dating an actress, Joyce Heyser, although she was living on the opposite coast. He preferred then to maintain a distance in all of his personal relationships. However, as he began sketching out his latest batch of songs in this isolated state, Springsteen also found himself considering the kind of life that he had to that point shunned: the notional idyll of settling down and raising a family, but having to do so against the backdrop of the ruinous recession blighting the US economy. The young, wide-eyed characters Springsteen had written about on Born To Run had been bent on escape from their confined, small-town existences. Darkness found them running headlong into dead-end jobs, shorn of hope and fighting a suffocating sense of dread and despair. Now he was looking inward for the answers to what might come next.

“I wanted to write for my age, you know?” he reflected in The Ties That Bind, the documentary film included in the recent box set re-release of The River. “By the time you’re thirty you have a clock that’s ticking – you’re definitely operating in the adult world. Part of The River was my trying to find the courage to jump in with both feet and experience those things for myself.”

Once Springsteen had thrown open this gateway, songs poured out. A bunch of them were reflective, uncertain pieces, such as Point Blank, Stolen Car and Independence Day, an imagined conversation with his father. These were counterbalanced by revved-up barroom rockers like Two Hearts and Out In The Street, songs through which he shrugged off the weight of the world. He ended up with 70 songs vying for inclusion on the record. He was of a mind to ditch one of these in particular, believing it to be too lightweight. In the event, both Van Zandt and Landau implored him to keep hold of Hungry Heart. It went on to be his first smash-hit single.

At one point Springsteen handed over a single 10-track disc, also titled The Ties That Bind, to Columbia, but then grabbed it back. He quickly concluded that it simply wasn’t big enough to contain the ranging landscape of the music he was making. He had also written yet another new song that felt like it should be a centrepiece: introduced by weeping harmonica, The River was a mournful tale of two young lovers hollowed out to a husk by hard times. In essence it was the story of his sister, Ginny, who’d got pregnant at 18 and married her construction-worker boyfriend.

Unfolding over four sides of vinyl and comprised of 20 tracks, The River was finally released on November 17, 1980. It debuted at No.1 on the Billboard chart and within a year had sold two million copies in the US. Less than a fortnight before it came out, Ronald Reagan was elected the 39th President of the United States, and Springsteen’s themes of struggle and of faith being tested resounded with the storms that were to go on assailing the country. Springsteen was now being perceived as a populist champion of America’s dispossessed and downtrodden. In that sense, The River completed the trilogy begun with Born To Run. Yet in its reach and ambition, it also pushed him up and over that hill and on towards an ever bigger inclination.

Coming off the road after 11 months of touring The River through the States and also for the first time around the UK and mainland Europe, Springsteen holed up in a rented house out in the New Jersey farm belt. Others in the E Street Band were returning to new normalities: Clemons had got married in Hawaii that September, with Springsteen as his best man, and Weinberg and Van Zandt were recently hitched too. Van Zandt, the only band member Springsteen saw socially, was also off making his first solo album. By contrast, Springsteen had just broken up with Joyce Heyser, and was no closer to claiming the life he had imagined for himself on The River than when he started out on that record.

“I’d had more success than I’d ever thought I’d have, we’d played around the world, and I thought, like, ‘Wow, is this it?’” Springsteen told James Henke of Rolling Stone in 1992. “Music provided me with a means of communication, a means of placing myself in a social context – which I have a tendency not to want to do. But the guy without the guitar was pretty much the same as he had been… Once out of the context of my work, I felt lost. I mean, I got really down, really bad for a while.”

He found the way to expressing the bleak thoughts spooking him through the books and movies he was consuming. Among these was Terence Malick’s chilling 1973 film Badlands, which Springsteen happened across late one night on TV. The film recounted the true story of 19-year-old Charles Starkweather, who in December 1957 embarked on a two-month killing spree through Nebraska and Wyoming, which landed him in the electric chair. Settling down to write a new record, Springsteen also thought back to his paternal grandparents’ house in nearby Freehold where he spent chunks of his childhood, and where in 1927 the couple had lost a daughter, hit by a truck on the road outside. “I was trying to capture the mood of what that house was like when I was a child,” he recalled to Ames Carlin. “Austere, haunted [and] just the incredible inner turmoil.”

In two months Springsteen pulled together a collection of songs joined up by their hushed tone and fatalistic mood. The characters that stalked them like spectral presences were made up of an underclass of the doomed and damned.

One morning he sent his guitar tech to the local electrical store to pick up an off-the-shelf Teac cassette recorder, and over the next two nights put down 15 songs on it. He recorded in his bedroom, perched on a wooden chair, its creaks audible on one track, Highway Patrolman. Each of the songs was acoustic, bare-boned and sung like a gallows hymn. The tape opened with the ghostly Nebraska, inspired by Malick’s movie. A song near the end of it was a weary-sounding lament to the fate of a Vietnam vet who’d come home to a country that had turned its back on him, titled Born In The USA.

Springsteen wrote in his 1998 lyrics collection, Songs, that in total, these tracks marked out a line “between stability and that moment when time stops and everything goes to black. When the things which connect you to your world – your job, your family, friends, your faith, the love and grace in your heart – [they all] fail you.”

In May 1982, Springsteen summoned the E Street Band, Landau and his trusted engineers, Toby Scott and Chuck Plotkin, back to the Power Station to begin working through the songs on the tape and others that were still then gestating. This latter batch included I’m On Fire, Darlington County and Cover Me, which Springsteen had meant to hand over to disco queen Donna Summer but that Landau once more entreated him to hang on to. Turned over to the band, these newer tracks at once burst into bloom. Those on the tape, though, stubbornly refused to yield to more resounding treatments. Whatever else the E Street Band brought to them, their versions lacked the fearful intimacy that made Springsteen’s demos so compelling. There was one exception: Born In The USA. The second take of it that Springsteen cut with the band during the sessions exploded onto tape and wound up leading off the album of the same name. For now, though, he set it to one side. He was not ready just yet to make that kind of noise.

Rather, he kept the band hammering away at the other, less pliable songs on his cassette, growing more frustrated with each unsatisfactory attempt. Eventually Landau blurted out to him one night that they consider releasing the tape itself as Springsteen’s next album. Springsteen bit, and instructed Scott to master the record from his home recordings. This proved to be yet another arduous exercise, since the cassette recorded had inadvertently been set to record at the wrong speed. Scott also had to painstakingly eradicate tape hiss. The whole process took months, but Nebraska, as Springsteen had decided to call the album, emerged from it a singular work – hushed and desolate, but powerful and evocative

Wrapped in a stark black-and-white cover depicting a deserted two-lane road photographed through a car windscreen, Nebraska was released on September 30, 1982 to glowing reviews. It came out at the same time as such polished, easy-on-the-ear blockbusters as Toto IV and Roxy Music’s Avalon, and just two months ahead of Thriller. It was also a time when the US was suffering double-digit unemployment. Narrating his own long, dark night of the soul, Springsteen also voiced the general gloom creeping out there in the country.

He did no interviews or touring to promote the record, and even elected not to appear in the first video he had commissioned for the nascent MTV. This was shot to back up Nebraska’s taster track, Atlantic City, no less subdued than the rest of the album but with a keening melody. It instead showcased images of the crumbling facades on the shoreline of New Jersey’s one-time gambling mecca. About as far from Jackson moonwalking as it was possible to get, Nebraska was nonetheless another platinum hit.

Not that the success of the record brought Springsteen any immediate solace, since for the rest of that year his mood remained dark and unstinting. Flitting between LA, where he had bought his first house, just off Sunset Strip, where he’d installed a state-of-the-art home studio, and a second property he shelled out for in Rumson, New Jersey, he spent the next five months writing yet more songs in solitude. To start with, these were close relatives of the Nebraska material, songs that stared down the barrel of a gun, but gradually Springsteen found his way back into the light. He had started seeing a psychiatrist out in LA, and back east in New Jersey began attending a gym. Besides performing and having a passion for surfing, Springsteen claimed to have avoided all other forms of exercise up to this point, and indeed appeared to exist on a diet confined to junk food. Soon enough, though, he was eating healthily, running six miles a day and lifting weights, bulking up his wiry, malnourished-looking frame.

All in all, it was as if he were engaged in an act of rebuilding and remaking himself. And that he was doing so to prepare for the task of hauling himself and his music up to the next level and then onwards to the boundless horizon beyond it.

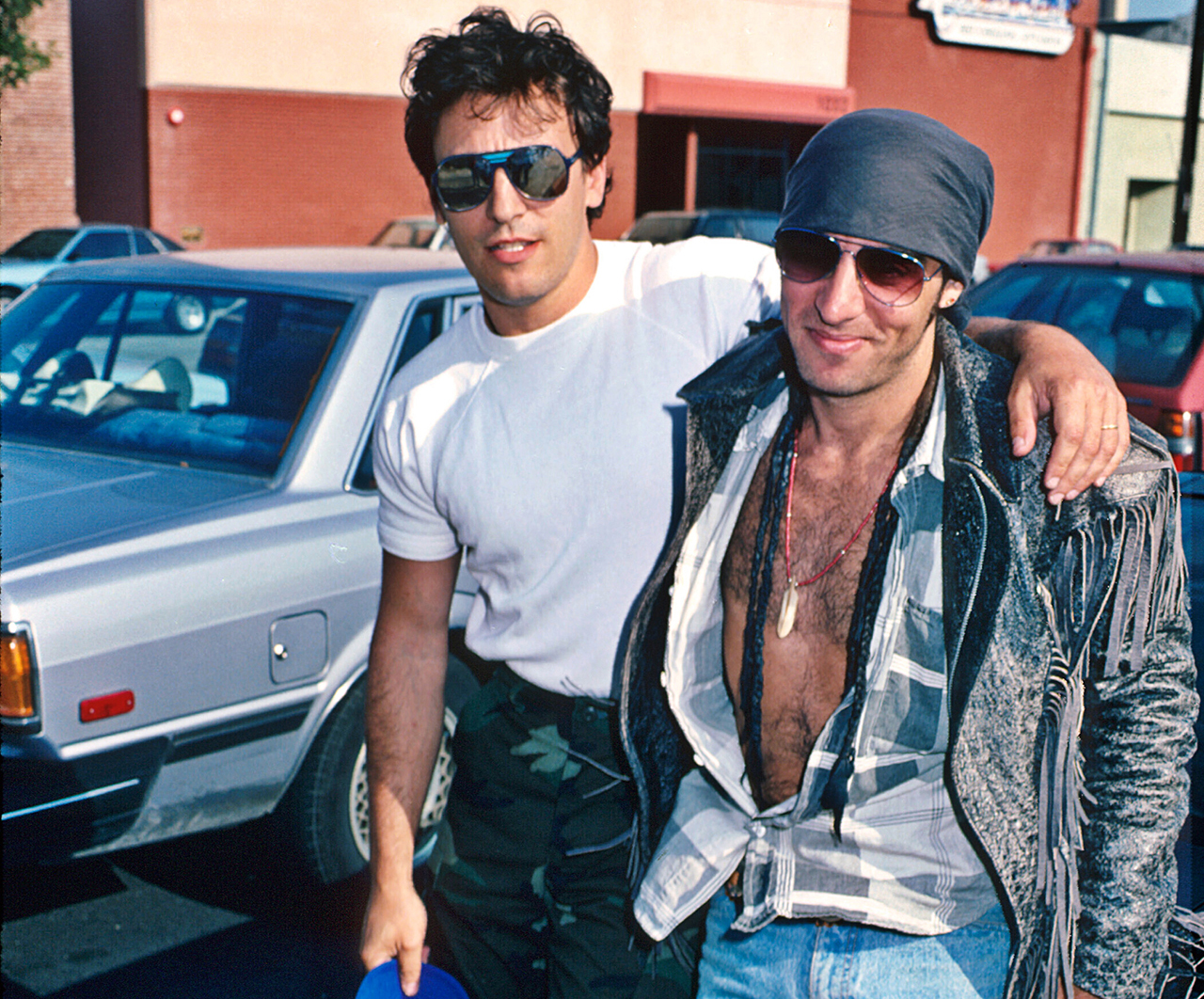

In September 1983, Springsteen again rounded up the E Street Band at the Power Station and another New York studio, the Hit Factory. The subsequent sessions were given impetus by a surging, R&B-flavoured rocker he had just written, although the upbeat musical backdrop to Bobby Jean was also concealing a hurt. Written as a bittersweet farewell to a lover, it was in fact aimed at least in part at Van Zandt, who had told Springsteen back in the spring that he meant to go off and have his own career. On this occasion Springsteen could not persuade him otherwise.

“All of a sudden I could tell [Springsteen] wasn’t hearing me,” Van Zandt related to Ames Carlin. “I wasn’t getting through. That was new to me and I wasn’t comfortable with it. I felt our relationship was in a little bit of jeopardy. And I thought the way to preserve the friendship was to leave.”

In spite of his consiglieri’s departure, Springsteen had recovered his bearings and over the next five months moulded the Born In The USA album into shape. The title track and another leftover from the original Nebraska tape, Downbound Train, were dusted down and put alongside songs dating from the May 1982 session, and a fresh burst of material that had yielded Bobby Jean and also the garage-rock outpouring of No Surrender and then Glory Days. By the following March, 15 completed songs were up for inclusion on the record, but Landau still felt they were missing a signature hit and told Springsteen as much. Springsteen barked back that he had written 60 new songs to that point, and if Landau believed he could do better then he could go and write his own fucking hit.

That same night, back at the Manhattan hotel where he was staying temporarily, Springsteen took up his acoustic guitar and wrote Dancing In The Dark in the hours before dawn. He recorded it with the band the next evening, completing an album that was chock-full of songs as instant and accessible as Hungry Heart, the breakthrough hit he had meant to give up. He had no such reservations regarding Born In The USA. In fact, quite the opposite was true this time around. Having until then zealously guarded how his songs were sent out into the world, Springsteen was soon handing over Dancing In The Dark and Cover Me to New York hip-hop producer Arthur Baker to be remixed as dance tracks, following the example of labelmate Cyndi Lauper. The hits from Lauper’s multi-platinum She’s So Unusual album of the previous year had been successfully reupholstered for the clubbing crowd.

“In the end [with Born In The USA] it was a variety of things that kind of threw the argument in one direction,” Springsteen told writer Dave Marsh. “But my feeling was that I’d created an opportunity for myself, and why cross the desert and not climb the mountain?”

In Annie Leibovitz’s famous cover photograph for Born In The USA, the newly muscled Springsteen, turned to face a backdrop of the Stars and Stripes, is framed as the archetypal strong, indomitable American hero figure, cut from the same cloth as Gary Cooper’s noble lawman in High Noon or Marlon Brando’s proud dock worker in On The Waterfront. The record itself was custom-built to come booming out of car radios and jukeboxes and, most of all, for the shiny new compact disc format. Buoyed by its video, shot by film director Brian de Palma, of Carrie and Scarface fame, on the opening night of the tour in St Paul, Minnesota on June 29, Dancing In The Dark rocketed up the Billboard Hot 100. The just-released album was pulled along in its slipstream, on its way to becoming a 30-million-selling colossus.

The Dancing In The Dark video presented Springsteen as an idealised version of his true self: sweat-drenched and in his natural environment, but larger-than-life now too, whisking the pretty girl from the audience and into a dream state. Out on the road he was packing out multiple nights in arenas across the States, but still able to assert his everyman credentials and keep a hold of things. In each stopover city on the tour he made donations from the nightly receipts to local food banks and Vietnam vets’ organisations. Fronting a fleshed-out E Street Band that now included Van Zandt’s replacement, Nils Lofgren – gnomish but extravagantly gifted, and whom Springsteen had also known since the early 70s – and flame-haired backing singer Patti Scialfa, a New Jersey native who had once auditioned for one of his bar bands, he kept right on conducting their epic shows in the spirit of revivalist meetings.

“All I saw when I was a kid was showmen,” Springsteen told me in 2009. “The doo-wop guys, like Sam And Dave. Those people believed the show was a tool of total communication – going out and doing some clowning, some preaching, making the band so tight and knocking those songs into one another with such furious pace that the audience couldn’t catch their breath. You left them exhausted and exhilarated.”

Born In The USA, though, took on a momentum of its own and slipped out from his control. 1984 was an election year in the US, and at a campaign stop in Hammonton, New Jersey that September, the incumbent President Reagan tried to hitch himself to Springsteen’s bandwagon. “America’s future,” Reagan announced, “rests in the message of hope in the songs of a man so many young Americans admire – New Jersey’s own Bruce Springsteen.”

Springsteen had largely avoided airing his political views up to that point, but it was obvious from even a cursory knowledge of his songs that he was in the opposite camp to the Republican Reagan. And he took exception to the president’s endorsement. On stage at Pittsburgh’s Civic Arena two nights later, Springsteen told his fans: “Well, the president was mentioning my name in a speech the other day and I kind of got to wondering what his favourite album of mine must’ve been, you know. I don’t think he’s been listening to this one.”

He then played the coruscating Nebraska song Johnny 99, whose protagonist, worn down from losing his job at the local car plant, ‘got a gun, shot a night clerk’ and begged to be put on Death Row.

Yet it was all but impossible for him to rein in his hugely expanding audience, and for many of whom he was nothing but the latest pop star. When the tour headed to Australia, Japan and Europe the following spring, rabid demand for tickets forced him to move up into stadiums, breaking a vow he had made not to. Back in the US that summer, playing 28 stadium dates, Springsteen appeared on occasions frustrated, niggled by persistent whooping and hollering during his quieter songs and originating from the massed newcomers to his congregation. He was also struggling to make himself heard during his monologues, a long-held feature of his shows and the means by which he had got across whatever might be foremost on his mind.

Inevitably, great success also changed both Springsteen himself and the world he inhabited. By the time the tour rolled into LA, he was rich beyond his wildest dreams and married to a fashion model. Wrestling with these new realities, Springsteen found himself turning back down the same dark, bumpy road that had led to Nebraska.

“I just kind of felt burned out,” he told Rolling Stone in 1992. “The whole image of me that had been created – and that I’m sure I promoted – it really always felt like, ‘Hey, that’s not me.’ I mean, the macho thing, that was never me. It’s funny what you create. But in the end, I think, the only thing you can do is destroy it.”

In the first instance, Springsteen tried to adapt to married life at his sprawling house in Rumson. A box set, Live 1975-1985, came and went, selling truckloads, and gradually he applied himself again to the task of staking out his next journey. He had his engineer Toby Scott come out to the property and help build a studio in the carriage house adjacent to the main building, and began writing songs that reflected his new reality.

To begin with these were sweet, tender love songs, such as All That Heaven Will Allow. Springsteen taped them solo with Scott engineering, and using his newly acquired Kurzweil synthesiser to add drums, horns and string sections. However, storm clouds were soon gathering on the horizon and occasioned by what Springsteen obliquely termed was his “coming to grips with the complexity of what I was finding out”.

“Juli [Julianne Phillips, who Springsteen had married in May 1985] was a lovely girl,” E Street Band keyboard player Roy Bittan revealed to Ames Carlin. “But [Bruce] just seemed like he was trying to be a different person. I think he was trying to develop a way of being on a social level. And Julianne wasn’t anywhere on his train of thought.”

On Nebraska, Springsteen had hidden his psychic wounds behind third-person characters, but now he held them up for scrutiny in confessional, self-lacerating songs like One Step Up, Two Faces and Brilliant Disguise. The doomed trajectory of his three-year marriage, and to whom it was he apportioned the blame for its failure, was made explicit in the first of these, an ominous trip into his heart of darkness, masquerading as a lilting lullaby. ‘When I look at myself I don’t see the man I wanted to be,’ he sang in a doleful voice. ‘Somewhere along the line I slipped off track.’

Tunnel Of Love was completed in seven months and rolled out on October 9, 1987. Peering out from the cover, attired in a black suit as if for a funeral, was a very different-looking Springsteen from the one of Born In The USA. But then the sound of the record itself was also from another place entirely. In essence it was Springsteen’s first fully grown-up album, a collection of subdued, stately songs laced with hard-won wisdom and an overpowering sense of regret. It went to No.1 on both sides of the Atlantic, but nonetheless scared off the gawkers who had flocked to Born In The USA – as Springsteen surely meant it to do.

Like Nebraska, Tunnel Of Love also ended up being almost a solo record. Springsteen had individual members of the E Street Band come out to Rumson to put down parts, but scant few of their contributions made the finished album. He contemplated doing a solo tour as well, but relented, although the subsequent dates were billed pointedly as ‘Bruce Springsteen’s Tunnel Of Love Express featuring the E Street Band’. And the set-lists were shorn of such staples as Thunder Road, Badlands and Born In The USA. Still, Springsteen and his cohorts together remained a formidable force.

Yet the tour wound up being the shortest they had undertaken since Born To Run, and was played out against an unfamiliar backdrop of negative headlines and revelations about Springsteen’s private life. On the European leg during the summer of 1988, Springsteen made public that he was in a relationship with Patti Scialfa. Soon after, Julianne Phillips filed for divorce. Around the same time, Mike Batlan and a second now‑former crew member, Doug Sutphin, filed a suit alleging that Springsteen had among other things failed to pay them overtime wages, in contravention of US labour laws. The case was subsequently settled out of court, but both events sheared chunks of veneer off the enduring but wholly unrealistic perception of Springsteen as being near-saintly.

Not much more than a year after wrapping up the Tunnel Of Love tour, Springsteen called up each member of the E Street Band, except Scialfa, with whom he was now living, and told each one of them he was dissolving the group. He meant, he said, “to do something else and you’re not going to be part of it for a while”.

“That was a really tough time for everyone,” Nils Lofgren says now. “Inevitably it hit harder the guys that had been there from the start. But you had a musical genius who was now in his late thirties and had only played with seven other people. Anybody that talented will need to spread their wings. Hey, it was what it was.”

Springsteen had by then also moved with Scialfa from New Jersey and into a palatial $14m house in Beverly Hills. “I kept my promises,” he reasoned to Jim Henke three years later. “I didn’t waste myself. I didn’t die. I didn’t throw away my musical values… I just felt like the guy who was Born In The USA had left his bandana behind, you know?”

He didn’t admit to it, but he had shed so much more than just that. For right then, at the end of his tumultuous 80s, he seemed to be in flight from many of the people and places that had helped shape and make him, like a man in search of a new and as yet indistinct set of answers. It was, in fact, just as he’d sung it in the previous decade: ‘Someday girl, I don’t know when, we’re gonna get to the place where we really want to go/But till then, tramps like us, baby we were born to run.’

His route to finding those answers proved potholed and circuitous. With Roy Bittan and a bunch of hotshot session musicians, Springsteen next made a brace of albums and released them simultaneously in March 1992. Human Touch was buffed to too fine a sheen; Lucky Town was grittier, but both sold disappointingly. Afterwards, he again flew solo on the understated The Ghost Of Tom Joad album of 1995.

Now married and the parents of a young son and daughter, he and Scialfa moved back to New Jersey the following year. Back in his home state, in 1999 Springsteen reconvened the E Street Band, with Van Zandt rejoining the line-up alongside Lofgren, for a euphoric reunion tour and then an album, The Rising, written from under and about the shadow of the 9⁄11 attacks on the US. It was a critical and commercial hit. Springsteen followed it with a further six records – some made with the band, some without – and toured regularly .

Time has been good to him, but it has nonetheless extracted its inevitable toll. Cancer took the E Street Band’s Danny Federici in April 2008, aged 58. Four years later, the big man, saxophone player Clarence Clemons, was claimed by a stroke at 69. Springsteen and the E Street Band, though, roll on, their shows together now benedictions to fallen comrades and more of a ritual than ever they were, and with The Boss having about him the air of one who is sure at last of his place in the grand scheme of things.

“I was talking to someone a while back,” he told me in 2009, “and said: ‘You look at my house – Bruce Springsteen lives there.’ Someday it’ll be ‘Bruce Springsteen used to live there.’ And someday after that, nobody’s going to remember who lived there. They’ll just drive on by down the highway. That’s the way it plays out. And I’m comfortable with that. The pursuit of immortality, I’ll chase that as hard and fast as the next guy. But I don’t kid myself about how much of it is in store for me.”