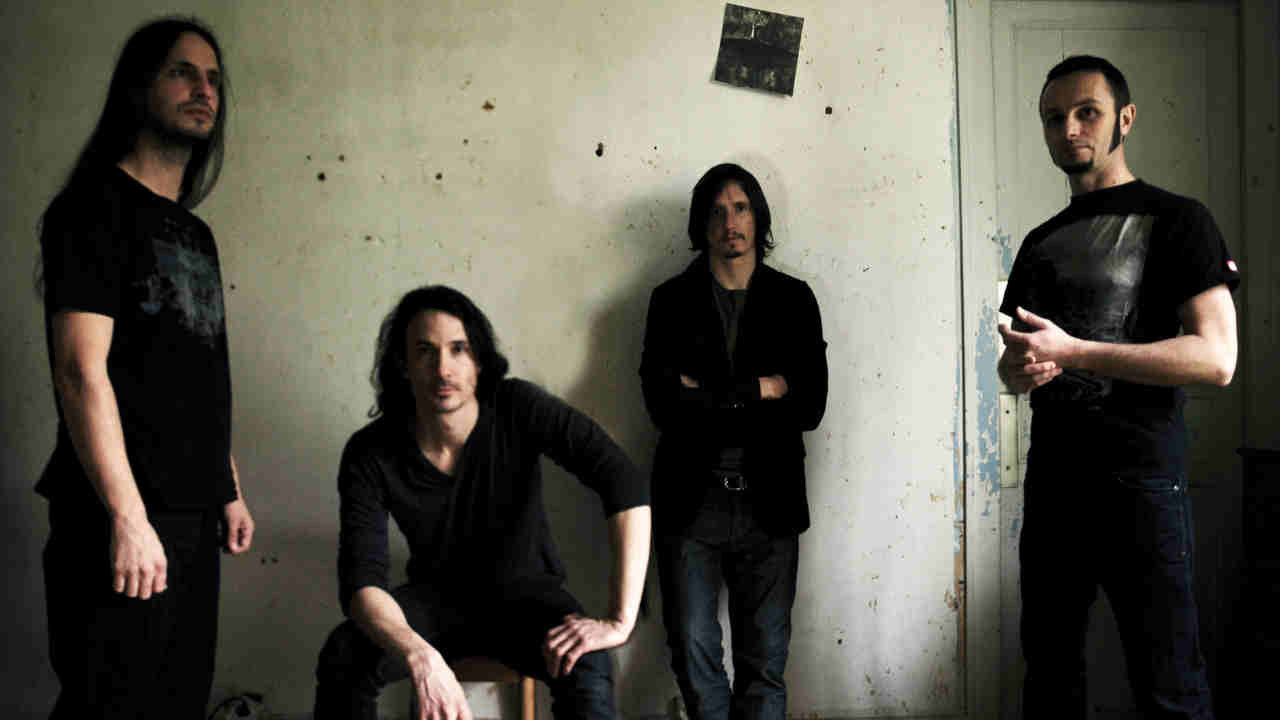

In 2012, French metal heroes Gojira returned after a four year break with the epic L’Enfant Sauvage album. Frontman Joe Duplantier sat down with Metal Hammer to talk anger, activism and the future of the planet.

As every regular reader of band interviews will know, if it wasn’t for rock’n’roll and heavy metal, our streets would now be overrun by tattooed and hair- teased psychopaths and serial killers. They’d be roaming the cities and the small towns of the US and UK mainly, possibly Belgium, their voracious ids unchecked by the strapping-on of guitars, the mostly melodic expression of personal woes and party pursuits and the adoration of variously numbered, empathetic fans.

And yet for all the countless potential monsters who have been saved from their life of frustration-induced crime and recrimination, the number of bands for whom music – and all that goes with it – has been a genuine calling, for whom a sense of something tantalisingly transformative radiating beyond the reaches of instant gratification, of something far bigger than them will shift the co-ordinates of ego, outlook and sheer physical conditioning into a devotional rite and way of life has been… pretty fucking small.

Which is only part of the reason why this rare category of bands – Tool, say, or Devin Townsend – tend to get treated with a particular kind of reverence and awe. Entwined with that is also the awareness that a) you couldn’t do it, and b) they’re like some kind of emissary, gaining access to the same spectrum of reverence and awe that flickers occasionally within your waking, worried hours and then overloading consciousness with it until There. Is. Nothing. Else.

You’ll get that within seven seconds of hearing Gojira’s, L’Enfant Sauvage. The brief, swelling drone of opener Explosia suddenly transports you, Dr Manhattan-style, right up against an unfathomably colossal network of shunting, scraping riffs as though they were the inner cogs of some sentient, clockwork deity before detonating a massive, kinetic groove throbbing like an urgent cosmic bulletin and opening up into a vast, mournful wake that suggests the last fires burning on a sea of phosphor.

An ambience-drenched, conveyor-belt pulse emerges and finally recedes into the distance once it’s propelled what’s left of you into the reaches of outer space. This is but the beginning of 52-minute journey that will constantly reconfigure your soul like a multi-dimensional Rubik’s Cube, seek out new vistas beyond even the scope of 2008’s The Way Of All Flesh, and in its densely detailed processes and elemental, all-encompassing presence, will give you unprecedented insight into what your life is worth.

Speaking to Hammer around the release of The Way Of All Flesh, Gojira’s frontman, Joe Duplantier, explained that the overriding theme of that album was death, the sense of purpose that get heightened when you face up to your own mortality. L’Enfant Sauvage’s voyage through stages of galvanising (ins)urgency, heart-rending sorrow and contrite yet fire- inciting self-examination seems determined to tear you apart and rebuild you with a hard- won, higher state of consciousness. Musically and lyrically (‘The old me didn’t survive/Inexorable transfiguration’, ‘And all shall die, transform’ being but two examples), the theme on the new album appears to be one of rebirth, of rigorous rite of passage.

Sitting in a photographic studio tucked away in a South West London industrial estate, as a two-person documentary film crew and the remains of two packs of Haribo look on, a relaxed yet lively Joe and brother, drummer extraordinaire and completing nucleus of the band, Mario, are explaining that this progression is the way of nature.

“I had this in my mind even before we started to record it or even compose,” Joe affirms. “I was like, OK, the last album was about death, this album will be about birth. It makes sense with the idea of the cycle, which is very present in our imagery. But then when we started to compose I completely forgot about this, but it still found its way in there. Of course there is a real cycle to everything, so there is also a certain rhythm to bands’ albums. Things do make sense in the end, I think, and even if you don’t consciously come up with a plan, you can always see it afterwards.”

This sense of transition is also one that’s drawn from the band’s personal and professional lives in the three and a half years since the release of The Way Of All Flesh, not least in the moving from long-term label, Listenable, based in their native France, to Roadrunner.

“Between these two albums,” explains Joe, “we had to find a new management and we changed record companies, so for a moment we were suspended in empty space, naked. In the dark. It was great at the same time; we could release an EP and nobody could tell us otherwise. We could have gone completely independent for example, so we had so many different ways in front of us, so many options, and finally we thought, you know what? We need help, we need support, we need a big push from a good record company with the right people and we need a good management, because I was self-managing for a while, and I hate this. So we had a very strong need of structure and we felt that we had a potential that we wanted to bring to its maximum, so let’s go for it. All this took a lot time and energy – a lot of energy, oh my God. Months and months of all this, having to make big decisions for our lives.”

“When we composed The Way Of All Flesh we took four months,” says Mario, “and now when I listen to the album I love it, but there is a little lack of precision on it. When we started the new album, I knew we had to work precisely, and I knew we needed to take our time. So we took eight months to compose it, and the spirit was true, because after every- thing was so uncertain, the fact that we would come back to music was huge. When we start to play there’s nothing else, there’s the music. And it always feels good to go back to ‘Weee-BOH-H-H-H-H-H’. And of course each time we play all these things that are around the band and all the experience and our private lives and everything comes into this and we recycle all these things into sound.”

Parallel to that shift in circumstances, to finding your co-ordinates temporarily scrambled and having to ask yourself very serious questions about who you are in order to move on, has also been an equally transitional shift in personal perspective.

“I remember this feeling when I was 25, 26,” says Joe, “trying to hide my weakness, and trying to come up with very spiritual and strong lyrics about time and space and what’s beyond all that, and the ultimate truth of life and the mysteries of life and death, and with time you just accept your weaknesses and your dark side a little better. And my feelings are like this: I’m jealous or I’m this or that… you’re a little wiser, so the lyrics are more honest. All of a sudden the anger can express itself like straight anger – you don’t hide it. So there is more experience and wisdom and the lyrics seem more angry or restless, like, ‘What the fuck? It’s so hard to be alive!’ OK, I'm going to write that down, because it’s true.”

Three months ago, while he was still recording vocals for the album, Joe became a father. How did that affect his perspective?

“Something changed in me, for the better definitely. I’m a better person since I became a dad, but in the sense that I care more. But this balance between the soul-searching and the analysing of the outside world was always there in the music. Fatherhood and birth is such an amazing thing. Birth is a miracle, there’s no other word. There are some cells getting together and creating a human shape inside of someone, and all of a sudden some- one is here, a consciousness, a personality, a voice, an attitude, a someone. My daughter is three months old but she has a strong character and she wants to stand up already. This is amazing, this is incredible, it just blows my mind. I’m glad to be alive and to have all these experiences. Sometimes they’re hard, sometimes they’re beautiful and it creates a material inside of me to put in the music.”

Deeply embedded into Gojira’s spiritual search has always been a concern for the environment. Right now, there’s a case to be made that it’s all going to shit. The cult of climate change denial, oil spillages, fracking and tar sand oil extraction are but a few of the rapacious enterprises being waged on our planet. Listen to L’Enfant Sauvage, to the tectonic grinding of The Gift Of Guilt giving way to aching, cyclic rhythms radiating an inconsolable grandeur, and to Joe’s restless howl as if surveying the ruins from above, and you can’t help but wonder whether the epic-scale melancholia, frustration and contrition that runs as a thread throughout the album is a direct response to our current state of despoilment.

“Yeah, absolutely,” comes Joe’s reply. “And anger. It’s hard when you’re sensitive about things and when you see things happening in the world, and you don’t need to trust the news or not trust the news, you just look around and see how things are going. You buy one little cookie in the supermarket and with this comes a lot of plastic. But when you’re so sensitive about everything, it’s very hard to avoid this feeling of being overwhelmed by anger and despair. It could go very far. So we have to accept the world and everyday life and people’s limits, people’s intelligence.”

“It seems that my main concern is to be as straight as possible with my emotions and sometimes they’re complex,” he continues. “For example, I love people and I hate people at the same time, right? I’ve a lot of passion, so of course hate and love mixed together, we can call this passion in a way. I’ve a lot of passion for life and it’s killing me and at the same time it’s uplifting. It seems like I see people’s potential and it makes me sad and angry when this potential is left on the side, and I speak for myself. For example, it takes a lot of discipline to reach your goals, so it seems like I’m pissed off at myself, actually.”

Not that Gojira aren’t above direct action. Having become involved with the pro-active anti-whaling Sea Shepherd Conversation Society – now considered a terrorist organisation by three developed countries – both through the ongoing saga of the unreleased charity EP, Sea Shepherd and the lending of their name to an interceptor boat amongst their fleet.

“It’s been going all over the world,” says Joe. “It’s one of the fastest boats on the planet, that’s so cool! But it was very useful for finding the boats, the Japanese fleet when they were hunting whales. They contacted me and said, ‘Hey dude, we just called our boat Gojira, you must be proud’, and they sent me pictures when they were painting it. But it just happened like that. We were like, ‘Damn, this is great’, but nothing really official happened, we didn’t even see the boat.

“Now they’ve changed the name because they’re really not friends with the Japanese, so they got sued because they were using a Japanese name [Gojira is Japanese for Godzilla]. So they changed it to Brigit Bardot. For us it was it was strange because everyone makes fun of her in France, although she did some great stuff for animals.”

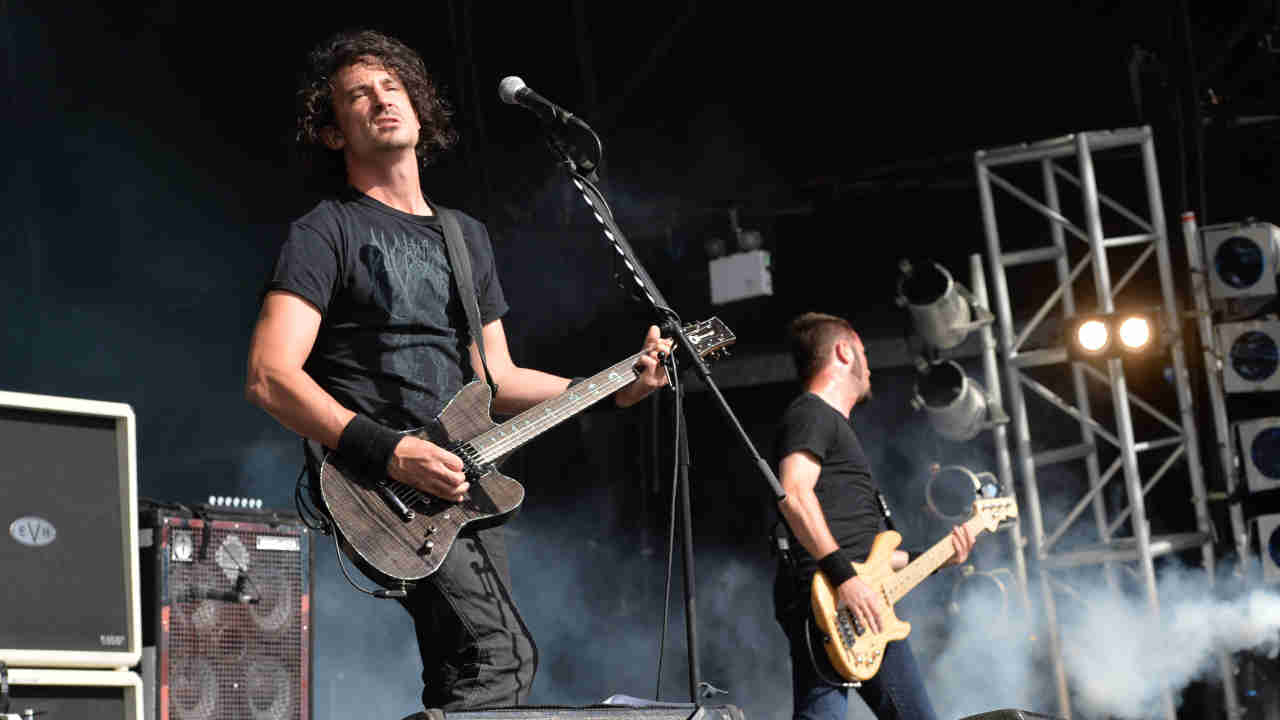

For all their talk of nature, both human and otherwise, there’s very little that’s organic in Gojira’s sound. If you thought the musicianship on The Way Of All Flesh took technicality to super- human but still deeply emotionally affecting levels, L’Enfant Sauvage’s precision-tooled mechanics are more mind-bending still, each song meticulously calibrated to probe and prise open parts of you that you secretly knew existed. Where does that clinical impulse come from?

“For me, it’s a little bit of a mix between martial arts,” replies Joe, “where you need to be super-precise and dancing almost. When you have a ballet where you have several people dancing together at the same time, it gives such a strong feeling, it can be really impressive. And that is pretty much what we do. Our fingers are dancing on the strings and we have to be perfectly synchronised with Mario’s legs. In a way it’s a kind of ballet.”

Would he call it a spiritual discipline?

“Absolutely. The level of concentration and dedication is so high that it pushes you to be at your best all the time, and on tour, with fatigue, it’s very easy to become lazy, just grab a beer and watch a movie in my bunk. It’s a typical rock star story that you can be drunk onstage and it’s fine. We cannot do that. We have to be super-focused and precise and tight, otherwise it’s not even interesting to do.”

There’s something about Gojira that’s absolute, a threshold that, once crossed over, becomes all-consuming. Few bands get to become a cause in their own right, both in terms of what they stand for and the unshakeable integrity by which they go about their art. Does Joe see his band in that company?

“Yeah, it’s very hard to talk about this without sounding pretentious, but we believe in what we do and we are the biggest fans of our music. It sounds strange to say that, but we work so hard, we dedicate our lives to this thing. But then we need to be humble about this, otherwise we’ll go fucking crazy. But it’s just hard work, dedication, making ourselves available to this energy and it’s totally normal that people like to see us onstage in the end, because we put so much into this. But of course we’re doing a certain style of music at a certain time and somehow it matches. Because we could be ahead of our time or too late, but are we lucky or are we in tune with our time? I don’t know, it’s really hard to tell. We’re not Metallica.”

And yet, having toured with Metallica, and with a new album that’s already world-beating in its own right, one whose startling sonic mass seems to warp the possibilities of what metal can achieve to their will, where do Gojira see themselves on the metal map? When the history books get written, will they have made a difference?

“I am convinced that we will somehow leave a mark,” Joe concludes. “It’s already the case. We are already part of this. We are not done with working and digging and the faith is really big also. It’s like we’re building an entity or something that is not us, but we’re just servants of this thing. We’re not finished yet.”

Originally published in Metal Hammer issue 232

![GOJIRA - L'Enfant Sauvage [OFFICIAL VIDEO] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/BGHlZwMYO9g/maxresdefault.jpg)

![Gojira - Explosia [OFFICIAL VIDEO] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/QqB4YPcacdo/maxresdefault.jpg)