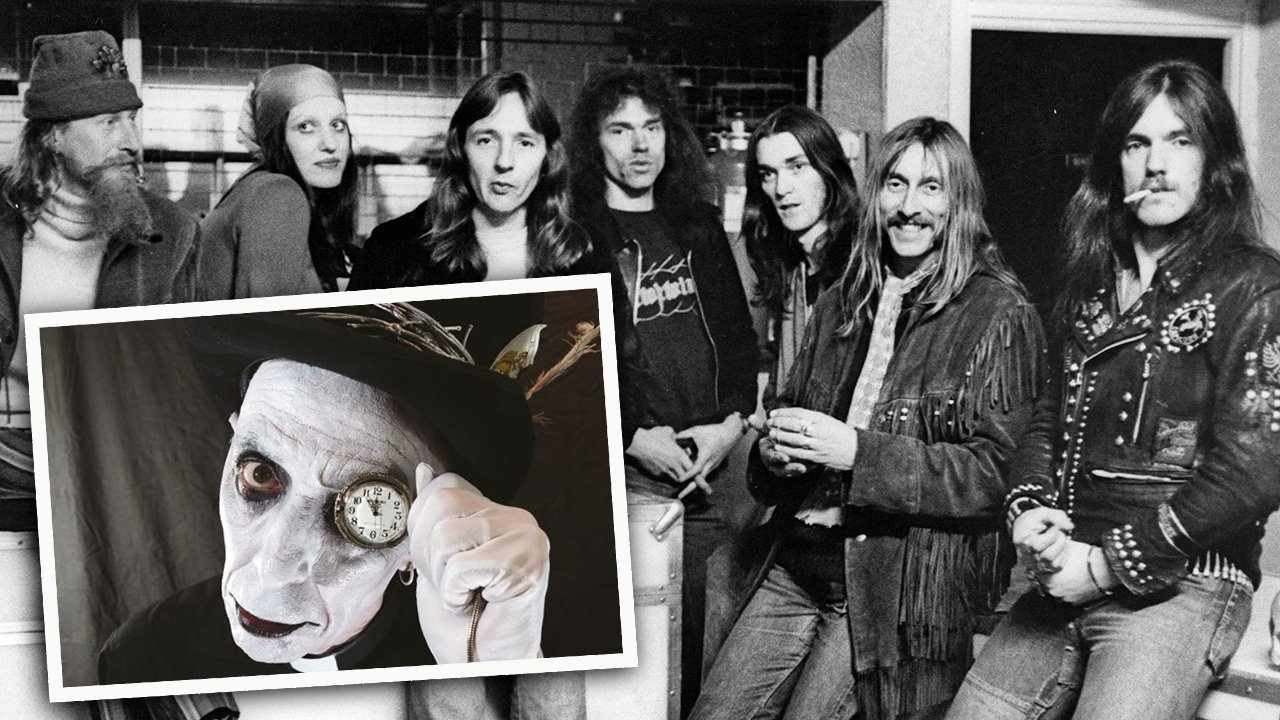

Gong at 50: how they made The Universe Also Collapses

In 2019, Gong approached their 50th anniversary with The Universe Also Collapses. We found out how they navigated their first release without any input without the late Daevid Allen

The next transmission from Planet Gong is about to arrive. As the radio signal traverses the Oily Way, two of the planet’s emissaries lead an advance party to the more prosaic environs of a London pub to prepare minds and spirits for its arrival.

The Universe Also Collapses will be the third Gong album to feature Kavus Torabi (Knifeworld/Cardiacs) as frontman and guitarist, and Dave Sturt (Steve Hillage Band/Jade Warrior) on bass. It will be the first to have no direct contribution from founder and master builder Daevid Allen, who returned to his home planet permanently in 2015.

The previous record, Rejoice! I’m Dead!, released in 2016, saw the fledgling five-piece coalesce and form their own identity under the Gong banner, visualising their next steps.

“Rejoice! I’m Dead! was our chance to work out what we were going to do after Daevid went,” says Sturt. “We weren’t sure what the response to that was going to be. We were really pleased with the way it went. We were accepted. It was a journey for us as well – we had no idea where that was gonna go.”

Kavus Torabi picks up the thread: “We thought the only way this is gonna work for us is if we can be the band Gong and not be a tribute band or a nostalgia act. We have to write stuff and we have to do it on our terms and if we can’t do it on those terms then we can’t do it.

“We could try and make records that sound like us trying to ape a certain era of Gong or we can take the players and the tools that we’ve got and try and do something Gong’s never done before. I feel this is more what Daevid got us together to do – to try and find different zones on the same planet. If we’re on that planet then we’re explorers. Daevid and Pierre Moerlen and Steve Hillage had mapped out this part of the territory, but we’re on the same planet still.”

2019 marks Gong’s 50th anniversary. As is the case with many bands who have been around this long and lost key members along the way, the acceptance Sturt mentions is not always universal. No one is more keenly aware of that than the current members themselves.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Torabi reflects on the time leading up to Allen’s death when it wasn’t clear what Gong could be or indeed if they could be. Could they be accepted wasn’t the burning question: they were asking if they accepted themselves.

“It’s not a position that any one of us ever planned to be in or initially felt comfortable about being in. None of us wanted to do it,” Torabi confesses. “I never asked to be ‘that prick that took over from Daevid Allen’. It was Daevid that wanted us to do it! We were just honouring the fact that we’d put out a new record, we’ve gotta tour it. We’ve got to do these gigs to promote the new record and then we’re out. And then something happened over those few gigs. Something new opened up.”

Those remaining live shows provided the impetus and the meaning for Gong to continue. One of Robert Fripp’s famous aphorisms states, “Sometimes music leans over and takes the musician into its confidence.” During those shows music took these musicians into its confidence and illuminated the way. Torabi elaborates how this came into being.

“A great deal of what Gong does on stage is improvised,” he explains, “so you have a song like You Can’t Kill Me and in the middle of that you have anything between a three- to a 10-minute improvised section, which will eventually come back into the tune again. Where we went sonically in that would differ from audience to audience. Each night we’d start to explore areas. After about a year of doing this we’d go into these bitonality areas and go back to the hotel and go, ‘Fucking hell! What about You Can’t Kill Me tonight? Boy, we really went somewhere!’ The following night we’d maybe go a bit further.”

Sturt corroborates: “What was great was that was the first song of the set so we’d only play a couple of minutes of this classic Gong track and then suddenly we were into music being created in the moment. It’s a real statement to say, ‘Yeah, we can do this and this is where the band’s coming from and this is where it’s going.’”

The other agents in that spontaneous composition are Ian East on the saxophone and flute, Fabio Golfetti on lead and glissando guitar, and drummer Cheb Nettles. As Sturt and Torabi talk about their almost spiritual experiences bringing new Gong music to life “in the moment”, their effervescence at playing with their bandmates spills over.

“For me, Cheb Nettles is the best Gong drummer since Pierre Moerlen,” says Torabi. “He is just a joy to play with. In Ian East, the minute the guy puts a horn in his mouth it’s instant Gong. We could show him the South Of Heaven riff [by Slayer] and he would make it sound like Gong! In a way, more than any of us, Ian was born to play in this band.”

“He even looks like Didier Malherbe,” Sturt observes. “He’s got the same jaw!”

“Then you’ve got Fabio whose gliss playing is just…” Torabi breaks off, lost for words. “The minute that guy picks that thing up the skies part and angels start singing.”

The Universe Also Collapses is not only a result of the music this quintet brought into being through improvising that classic catalogue, but conceptually and lyrically it holds up a mirror to the entirety of Gong’s 50-year existence. Taking its cue from quantum physics, psychedelic hallucinogens and meditations on the nature of time, it posits the theory that everything that has been or ever will be occurs in the same moment. A key lyrical phrase implores, ‘Remember there is only now.’ Time is the key.

“It does feel like scientists are generally getting closer to what the hell this is all about,” muses Sturt. “Mystics from generations back have known that from taking the right kind of psychedelics or just being that way inclined. High-functioning people can often get to that state.”

“With the idea of a psychedelic trip,” Torabi explains, “but also with the album itself being about everything happening all at once and constantly, there are a lot of repeated phrases musically and lyrically that keep coming back. You have these waves even through the other songs. When you have a few more listens you’ll start noticing these themes keep popping up and coming back. It was written very deliberately like that.”

The opening track of the album, Forever Reoccurring, is a prime example of this collision and collusion of science and mysticism. A 20-minute mantra-like epic, it is structured around mathematical patterns.

“It’s a very interesting track,” states Torabi, “because the whole track maps onto this 30-beat cycle…”

“I always think of it as two lots of 15!” Sturt interjects, starting the kind of argument you don’t get in many genres.

“You can subdivide it in a lot of different ways,” Torabi says. “Six bars of five, five bars of six… Ian was very keen that whatever we do with this track let’s keep the maths, this sacred mathematic vibe. My approach was, ‘Man, fine but what if we have a really good idea?’ I don’t want to shoehorn in some fucking maths just to make it flow!

“As it happened, nothing ever felt awkward. It keeps shifting within that cycle but it always sticks to it and it’s really great to have been able to make something where you don’t feel like you’re looking at the graph paper, but it does have this wonderful formula bubbling underneath it.

“That just grew out of one riff then at some point we were like, ‘Hang on a minute this is gonna be like fucking side one, right?!’ It was really exciting to do our Close To The Edge!”

The album was conceptualised in post-gig resident bars during that tour, not just from discussions about their emergent sound but its overall shape and message.

“We said, ‘Let’s make a really psychedelic record,’” states Torabi. “It’s not gonna be a prog record or jazz record, let’s just think about a psychedelic record. We want the songs to be propulsive and static and upwards and pulsing.”

The album is structured to convey the experience of the various stages of an LSD trip.

“It starts off,” Torabi illustrates, “with the build-up of the revelation, then you hit the ecstatic moment, then you have the epiphany, then you get My Sawtooth Wake, which is the real dark voyage of the soul – the introverted existential angst. The Elemental is as you’re coming down – the visionary experience can’t be mapped out in language so you take so little of it back with you. The Elemental is like the brochure that sums up what that was all about.”

Gong as an entity is forever reoccurring, constantly shape-shifting and regenerating to bring its music and message to whoever wants to tune into its frequency. There is a real sense that Gong 2019 has its own essence outside the individual players, but naturally that essence flows into the stream of every other embodiment of the collective there has ever been: ‘You are I or I am you,’ as Daevid Allen put it. Kavus Torabi has his own analogy for the circularity.

“Being in Gong is like Doctor Who – the Octave Doctor Who!” he laughs. “Each Doctor brings their own thing to it. Each scriptwriter, each director brings their own take, but you’re still following. This Doctor is still Patrick Troughton or Peter Davison. We’re

still following the same message of the original Gong. We haven’t gone off-script.”

Steve Hillage has guested at many of their recent gigs which has led to him asking Gong to play as his backing band for a tour later this year.

“One of my biggest influences as a kid,” Sturt reveals, “was watching Tubular Bells live on TV with Hillage and Pierre Moerlen. That was so instrumental in my saying, ‘That’s what I wanna do.’ Now I’m playing with him it’s such a thrill.

“Every time he comes off stage he’s so happy. I think he’s better than ever actually. The last few gigs we did with him were bloody astounding! He’s just so thrilled to be playing with the band. There’s such a great vibe he said it was as good as the 70s. He can just relax and really enjoy it.”

“There’s a guy who has not lost his chops!” says Torabi, wide-eyed with admiration, “When he solos there’s the glorious Steve Hillage stratospheric guitar playing. Steve said, ‘You guys have brought the psychedelia back into Gong again,’ which is just what we wanted to hear.”

“This is the direction Daevid wanted to go in,” Sturt reveals, “but he was restrained more than we are by the past and what he felt the audience required. Half of him was desperate to break off and do something new. Half of him was held back and he had to play that part. He had to be that character.”

“Daevid very much had a vision of his own,” Torabi says, “in terms of his spirituality and how he viewed life and death. We can only bring our truth to this – I can’t just cop Daevid’s schtick, which is why we don’t go down this Pot Head Pixies thing. That was Daevid’s world. That was his vision.”

With a busy 50th anniversary looming, Gong are celebrating the totality of their history and mystery in the present moment. “I hate to say this,” Torabi notes philosophically, “but this is the longest-running stable line-up ever. I’m sure we could change all that!”

This article originally appeared in Prog 98.

Buy the latest issue of Prog Magazine.